Chapter 9: Lower Extremity and Gait

Objectives:

- Describe the functional motions of the knee, foot, and ankle.

- Identify the primary muscles of the leg that cause flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction.

- Identify the muscles of the lateral compartment, anterior compartment, superficial posterior compartment and deep posterior compartment of the lower leg.

- Diagnose the disorders/dysfunctions of the knee and lower leg and their treatments.

- Perform various provocative testing to determine different knee disorders.

- Identify the primary muscles responsible for ankle inversion/eversion, foot plantarflexion and dorsiflexion, foot pronation/supination, and toe flexion/extension.

- Understand how the foot and ankle function with respect to gait.

- Define basic gait terminology used for measurement and classification.

- Define the phases of gait.

Knee Anatomy

The anatomy considerations of the knee, foot, and ankle govern movement of the lower extremity. The femur articulates with the hip at the acetabulum of the pelvis. Important landmarks on the femur for the site of attachment of muscles such as the piriformis and psoas include the greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter, respectively. On the posterior surface of the distal femur are the medial condyle and the lateral condyle. Distally, the patella, tibia, and fibula comprise the lower portion of the leg. The fibular head is a common site of somatic dysfunction and articulates with the lateral condyle of the femur. The tibia and the fibula distally articulate with the ankle mortise (flanked by the medial malleolus) which provides articulation with the bones of the foot, the tarsals, the metatarsals, and the phalanges. The lateral malleolus articulates with the calcaneus, which in turn articulates with the bones of the foot. The region between the tibia and the fibula is the interosseous membrane; a similar structure exists between the radius and the ulna in the upper extremity. The angle of the head of the femur is the angle formed between the neck and shaft of the femur; the angle is normally 120o – 135o. If the angle is <120o, coxa vara is present; if the angle is >135o, coxa valga is present. The muscles of the lower extremity include those listed in Table 9.1. Compartment syndrome results from an increase in intra-compartmental pressure and is a surgical emergency due to potential circulatory compromise; the anterior compartment is often the most affected.

| Thigh muscles | Flexors:

|

Extensors:

|

Adductors:

|

Abductors:

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg compartments | Superficial posterior:

|

Deep posterior:

|

Lateral:

+ Fibularis and Peroneus both used |

Anterior:

|

| Origin | Insertion | Action | Innervation | Schematic (from Thieme) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

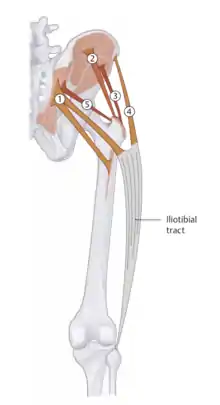

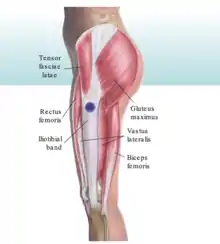

| Iliotibial band | Anterolateral iliac tubercle portion of the external lip of the iliac crest | Lateral condyle of the tibia |

|

No innervation; fibrous tract |  Iliotibial (IT) band |

| Gastrocnemius |

|

Calcaneal tuberosity via Achilles tendon |

|

Tibial nerve (S1, S2) | .png.webp) 1 - triceps surae (gastrocnemius) |

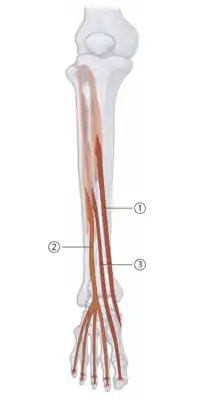

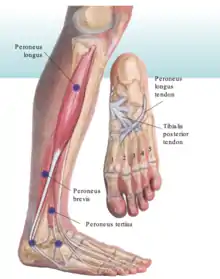

| Fibularis (Peroneus) muscles |

|

|

Plantarflexion, eversion | Fibular nerve (L5, S1) |  Fibularis (Peroneus) muscles: 1 - longus, 2 - brevis, 3 - tertius |

| Tibialis anterior | Upper 2/3 of the lateral surface of the tibia, crural interosseous membrane, and superficial crural fascia | Medial and plantar surface of medial cuneiform; medial base of first metatarsal |

|

Deep fibular nerve (L4-L5) |  1 - Tibialis anterior |

| Popliteus | Lateral femoral condyle | Posterior tibial surface | Flexion and internal rotation of the knee | Tibial nerve (L4-S1) |  4 - Popliteus |

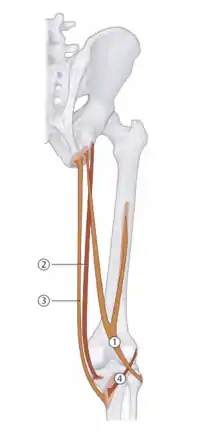

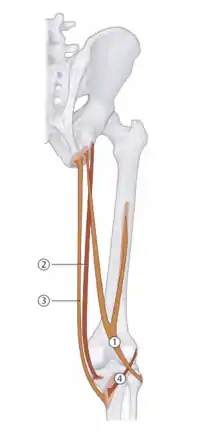

| Semimembranosus | Ischial tuberosity | Medial tibial condyle |

|

Tibial nerve (L5-S2) |  2 - Semimembranosus |

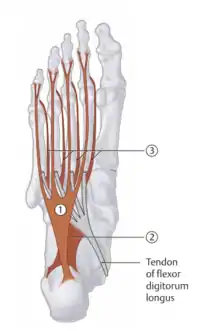

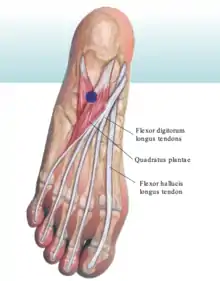

| Quadratus plantae | Medial and plantar borders on the plantar side of the calcaneal tuberosity | Lateral border of the flexor digitorum longus tendon | Redirects and augments the pull of flexor digitorum longus | Lateral plantar nerve (S1-S3) |  2 - Quadratus plantae |

Table 9.2 - Muscles implicated in lower extremity somatic dysfunctions

The articular disks of the knee-joint are called menisci because they only partly divide the joint space; these two disks, the medial meniscus and the lateral meniscus, consist of connective tissue with extensive collagen fibers containing cartilage-like cells. The menisci serve to protect the ends of the bones from rubbing on each other and to effectively deepen the tibial sockets into which the femur attaches. They play a role in shock absorption and may be cracked or torn when the knee is forcefully rotated or bent as a result of trauma.

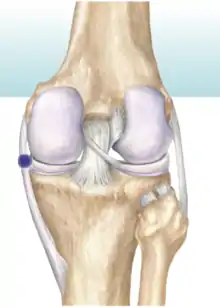

The knee is stabilized by a pair of cruciate ligaments; these are also classified as extrinsic ligaments of the knee. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) spans the lateral condyle of femur to the anterior intercondylar area. The ACL is especially important because it prevents the tibia from being pushed excessively anterior; it is often torn during torsion or bending of the knee. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) extends from the medial condyle of femur to the posterior intercondylar area. Injury to this ligament is uncommon but can occur as a direct result of trauma. This ligament prevents excessive posterior displacement of the tibia. The patellar ligament (also called the patellar tendon) connects the patella to the tuberosity of the tibia.

The intrinsic ligaments of the knee include the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) spans the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial tibial condyle. It is composed of three groups of fibers, one stretching between the two bones, and two fused with the medial meniscus. The MCL is partly covered by the pes anserinus (which serves as the distal attachment of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles) and the tendon of the semimembranosus passes under it. The MCL protects the medial side of the knee from being bent open by a stress applied to the lateral side of the knee (a valgus force). The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) extends from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of fibula; it functions to protect the lateral side of the knee from an inside bending force (a varus force).

The Q angle is the angle formed by the intersection of a line from the ASIS through the middle of the patella, and a line from the tibial tubercle through the middle of the patella. The normal Q angle range is 10o–12o. Two common deformities of the knee are genu varum (decreased Q angle) and genu valgum (increased Q angle). Genu varum is a deformity marked by outward bowing of the knees (“bow-leggedness”). On exam, the medial arch of the foot will be noted to be higher on the affected side. Genu valgus is a deformity marked by the knees angling inward and touching when the legs are straightened (“knock-kneed”). Patients with genu valgus are unable to touch their feet when their legs are straightened. A useful mnemonic is “gum” causes the knees to stick together when the genu valgum deformity is present.

Upon physical examination of the knee, several provocative tests can be utilized to assess ligament integrity:

| Ligament tests |

|---|

| The valgus stress test assesses the MCL. To perform this test, the knee is flexed to 30o to start, and a valgus (lateral) stress is applied to the knee. If there is medial glide of the tibial plateau, an MCL injury is likely present. |

| The varus stress test assesses the LCL. To perform this test, the knee is flexed to 30o to start, and a varus (medial) stress is applied to the knee. If there is lateral glide of the tibial plateau, an LCL injury is likely present. |

| The anterior drawer test and posterior drawer test are used to assess the ACL and PCL, respectively. To perform these tests, the patient is supine with the hips flexed to 45o, the knees flexed to 90o, and the feet flat on the table. The physician sits on the table in front of the knee being tested and grasps the tibia just below the line of the knee. The thumbs are placed along either side of the patellar tendon. The tibia is then drawn anteriorly. The test is positive if there is excessive anterior displacement of the tibia. Likewise, the posterior drawer test is done by applying a posterior force to the tibia. The test is positive if there is excessive posterior displacement of the tibia. |

| Lachman’s test is used to diagnose ACL injury; it can be viewed as a modified anterior drawer test. To perform this test, the knee is flexed to 30o with the patient supine. The physician placed one hand behind the tibia and the other hand grasps the patient’s thigh with the thumb on the tibial tuberosity. The tibia is pulled forward to assess the amount of anterior motion compared to the femur. If increased forward displacement is demonstrated, the test is considered positive. |

| Example: Provocative testing of the knee |

|---|

| A 20-year-old male presents to the office for evaluation of right knee pain. He states that he is very athletically active and notes that the pain began approximately one week ago. On exam, with the right knee flexed to 90o, a posterior force on the proximal tibia resulted in posterior glide that was very significant compared to the left leg. Anterior force on the proximal tibia was unremarkable bilaterally. Valgus and varus testing were unremarkable. The ligament that is most likely injured is the posterior cruciate ligament given the negative anterior drawer test and the positive posterior drawer test as noted. |

Upon physical examination of the knee, several provocative tests can be utilized to assess meniscus integrity as well:

| Meniscus tests |

|---|

McMurray’s test can be used to assess both the medial and lateral menisci tears.

|

| Apley’s Compression/Distraction test can also be used to assess meniscal and ligamentous tears, respectively. The patient lies in the prone position with the knee flexed to 90o. The patient’s posterior thigh is then pressed to the examining table with the physician’s knee. The physician medially and laterally rotates the tibia, combined first with distraction, while noting any restriction, excessive movement, or discomfort. The process is repeated using compression. If rotation plus distraction is more painful or shows increased rotation relative to the normal side, the lesion is probably ligamentous. If the rotation plus compression is more painful or shows decreased rotation relative to the normal side, the lesion is probably a meniscus injury. |

| The bounce home test is a test for decreased knee extension. With the patient supine, the physician flexes the knee while holding the heel. The knee is allowed to extend passively and should have a definite endpoint. It should “bounce home” into extension. A positive test occurs when full extension cannot be attained, and a rubbery resistance is felt. Fluid in the knee joint prevents the joint from bouncing home. Causes for a positive test may be a torn meniscus, loose body, intracapsular swelling, or fluid in the knee joint. |

| The patellar grind test is used to assess for chondromalacia. With the patient supine, the patella is pushed superiorly and held. The patient is asked to contract the quadriceps muscles. The test is positive if the patient expresses pain or grind is palpable. |

Knee Somatic Dysfunctions

Considering somatic dysfunction of the knee, fibular head dysfunctions are often encountered. The tibiofibular joint couples the motion of the fibula and the ankle. The fibular head is palpated and range of motion testing is done by comparing eversion and inversion of the ankle. Eversion of the ankle causes anteromedial rotation of the fibula on the tibia. Anterior fibular head somatic dysfunction arises as a result of preference of ankle eversion; the patient will prefer posterolateral rotation of the fibula on the tibia. Inversion of the ankle causes posterolateral rotation of the fibula on the tibia. The fibular head will show a shallow preference on evaluation. Posterior fibular head somatic dysfunction arises as a result of preference of ankle inversion. The fibular head will show a depressed preference on evaluation.

| Example: Fibular head somatic dysfunction |

|---|

| Consider a patient who presents complaining of tenderness along the proximal lateral lower leg. Provocative testing of the knee is unremarkable. While assessing ankle motion, the patient shows preference for inversion of the ankle and restriction with eversion of the ankle. This is a posterior fibular head somatic dysfunction, with restriction seen in motion of the anterior fibular head. Compression of the common fibular nerve can result in paresthesias in the lower extremity and can be exacerbated by posterior fibular head somatic dysfunction. |

Hypertonic muscles listed in Table 9.1 can also be treated with counterstrain techniques and will be described in the treatment section.

Treatment of Knee Somatic Dysfunctions

Anterior and posterior fibular head somatic dysfunctions can be treated with post-isometric relaxation muscle energy:

| Anterior Fibular Head Post-Isometric Muscle Energy: The patient is supine. The physician contacts the anterolateral aspect of the fibular head with the thumb closer to the patient's knee and internally rotates the patient's foot until the restrictive barrier is reached. The patient is told to externally rotate the foot and the physician will resist the motion with an isometric counterforce. In each respective iteration, the patient is taken further into the restrictive barrier. |  Anterior Fibular Head Post-isometric Relaxation Muscle Energy |

| Posterior Fibular Head Post-Isometric Muscle Energy: The patient is supine. The physician places the hand closest to the knee in the popliteal fossa so that the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger approximates the posterior fibular head and, with the other hand, externally rotates the patient's foot until the restrictive barrier is reached. The patient is told to internally rotate the foot and the physician will resist the motion with an isometric counterforce. In each respective iteration, the patient is taken further into the restrictive barrier. |  Posterior Fibular Head Post-isometric Relaxation Muscle Energy |

Anterior and posterior fibular head somatic dysfunctions can also be treated with HVLA:

| Anterior Fibular Head HVLA: | The patient is supine. The knee is placed in slight flexion (may use a small pillow) and the ankle is internally rotated to bring the proximal fibula anteriorly. The physician places the heel of the cephalad hand over the anterior surface of the proximal fibula and delivers a thrust through the fibular head toward the table while simultaneously internally rotating the ankle. |  Anterior Fibular Head HVLA |

| Posterior Fibular Head HVLA: | The patient is prone and the dysfunctional knee is flexed to 90 degrees. The physician places the metacarpophalangeal joint of the cephalad index finger behind the dysfunctional fibular head and the hypothenar eminence is angled down into the hamstring musculature to form a wedge behind the knee. The physician's other hand gabs the ankle and flexes the knee to the restrictive barrier. The foot and leg are gently externally rotated and a thrust is applied in a manner that would normally result in further flexion of the knee (which is prevented by the physician's hand). |  Posterior Fibular Head HVLA |

Tenderpoints which can be treated with counterstrain are found on the medial meniscus and the lateral meniscus:

| Tenderpoint | Location | Treatment position (initial setup) | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial Meniscus: | Medial aspect of the knee at the medial joint line with the medial collateral ligmanet and medial meniscus. | Patient is supine. Hip and thigh are abducted so the leg is off the table. The knee is flexed to 40 degrees. Slight adduction and internal/external rotation and ankle plantarflexion/inversion may be needed to optimize the initial setup. (F Add IR) |  Medial Meniscus Counterstrain |

| Lateral Meniscus: | Lateral aspect of the knee at the lateral joint line with the lateral collateral ligmanet and lateral meniscus. | Patient is supine. Hip and thigh are abducted so the leg is off the table. The knee is flexed to 40 degrees. Slight abduction and internal/external rotation and ankle dorsiflexion/eversion may be needed to optimize the initial setup. (F Abd IR/ER) |  Lateral Meniscus Counterstrain |

Foot and Ankle Anatomy

The regions and bones of the foot include the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. The hindfoot is comprised of the talus and calcaneus bones; the midfoot is comprised of the cuneiform bones (which have the greatest articulations with the corresponding phalanx), the cuboid bone, and the navicular bone; and the forefoot contains the metatarsals and the phalanges.

The ranges of motion for the foot and ankle 40-50o for plantarflexion and 20-30o for dorsiflexion. Inversion and supination have a range of 60o; eversion and pronation have a range of motion of 30o.

The three arches of the foot are the lateral arch, the medial arch, and the transverse arch:

- The lateral arch is primarily formed by the calcaneus, the cuboid, and the fourth and fifth metatarsals; it is supported by the long plantar ligament.

- The medial arch is formed by the talus, navicular, the three cuneiform bones, and the first metatarsal; it is supported by the plantar fascia and the tibialis posterior muscle.

- The transverse arch is formed by the cuboid, navicular, three cuneiforms, and the proximal metatarsals; it is supported by the fibularis longus and the tibialis anterior muscles.

The plantar fascia originates on the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and fans out over the bottom of the foot to insert onto the proximal phalanges and the flexor tendon sheaths. It serves as a shock-absorber as well as an arch support.

The motions of the foot and ankle are paired:

- Plantarflexion is accompanied by adduction and supination of the foot. This motion also carries the lateral malleolus anteriorly. Through the reciprocal action of the fibula, the proximal fibular head also glides posteriorly and inferiorly. The talus glides anteriorly placing the narrow portion of the talus in the ankle mortis, which is a relatively less stable position (compared to dorsiflexion, see below).

- Summarizing: plantarflexion, supination, and inversion.

- Dorsiflexion is accompanied by abduction and pronation of the foot. This motion also carries the lateral malleolus posteriorly. Through the reciprocal action of the fibula, the proximal fibular head also glides anteriorly and superiorly. The talus glides posteriorly placing the wider portion of the talus in the ankle mortis, which is a more stable position (compared to plantarflexion).

- Summarizing: dorsiflexion, pronation, and eversion.

The lateral ligaments of the ankle include the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament, and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL). Medially, the deltoid ligament is made of the anterior tibiotalar, tibionavicular, tibiocalcaneal, and posterior tibiotalar ligaments. The plantar calcaneonavicular ligament also helps to maintain the medial arch.

Ankle sprains are more likely to occur when the tibiotalar joint is plantarflexed. When considering ankle sprains, inversion sprains occur more frequently than eversion sprains because of the relative strength of the deltoid ligament. The tibiotalar joint involves the talus moving into the ankle mortise. The major motions of the ankle mortise are dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Dorsiflexion is functionally more stable of the two positions because the talus is structurally wider anteriorly and fits more securely with the posterior glide component.

Traumatic inversion strains the fibularis longus and fibularis brevis muscles. Shortening of those muscles pulls the fibula inferiorly and posteriorly. The plantar attachment of the fibularis longus pulls the first cuneiform metatarsal joint inferiorly, stressing and flattening the medial arch. This is all compounded by the sprain of the lateral ankle ligaments to varying degrees, leading to joint instability.

Pes planus ("flat-footed") is a postural deformity in which the arches of the foot collapse, with the entire sole of the foot coming into near-complete contact with the ground. The head of the talus bone is displaced medially and distal from the navicular bone; the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle are so stretched that the arch disappears.

Foot and Ankle Somatic Dysfunctions

When considering somatic dysfunctions, there are four key regions to consider:

1. The ankle mortise talocrural joint (tibia on talus):

- To assess tibia on talus somatic dysfunctions, the anterior and posterior drawer tests are used. (These tests are not to be confused with the tests of the same name for the knee.) To perform the anterior drawer test, grip the tibia and fibula with one hand and with the other grip the heel and the talus. Translate the foot anteriorly and posteriorly while assessing for restriction. To perform the posterior drawer test, perform the test in the opposite directions. Additionally, fibular head dysfunctions are associated with tibia on talus dysfunctions to the same side (i.e. posterior fibular head dysfunction is associated with posterior tibia on talus dysfunction).

- An anterior tibia on talus somatic dysfunction is present if the anterior drawer test is positive, if there is a deep malleolar sulcus, and the ankle prefers dorsiflexion.

- A posterior tibia on talus somatic dysfunction is present if the posterior drawer test is positive, if there is a shallow malleolar sulcus, and the ankle prefers plantarflexion.

2. The subtalar region (talocalcaneus):

- To assess the subtalar region, the physician grips the talus just below the malleoli, cups the calcaneus with the other hand, and translates the calcaneus from left to right while assessing for ease and restriction. Inversion and eversion occur at the subtalar joint and are evaluated when checking for somatic dysfunctions.

3. Midfoot (navicular bone, cuboid bone, cuneiform bones):

- To assess the midfoot, each tarsal bone is evaluated in turn in terms of superior and inferior motion, restriction, tenderness, and supination and pronation.

4. Forefoot (metatarsal and phalanges):

- To assess the forefoot, the physician grips the calcaneus and assess for supination and pronation, abduction and adduction, restriction, and tenderness on the metatarsals, particularly the heads of the metatarsals. Special attention should be paid to the second and third metatarsals.

| Example: Posteriorly displaced cuboid bone |

|---|

| If a patient presents with pain anterior to the heel on the outside of the right foot and demonstrates little motion over the site while the physician palpates a slight inferior bulge, cuboid is posteriorly displaced. (Patients will often describe a sensation of a “pebble in the shoe”.) |

Treatment of Foot and Ankle Somatic Dysfunctions

Plantarflexion somatic dysfunctions and dorsiflexion somatic dysfunctions may be diagnosed while assessing the paired motions of the foot. The treatment of choice for correcting dorsiflexion and plantarflexion somatic dysfunctions is muscle energy by utilizing the opposite paired motions in a post-isometric relaxation and direct fashion. The foot is taken further into the restrictive barrier with each respective iteration of the treatment technique.

| Example: Plantarflexion somatic dysfunction |

|---|

| A patient who wears high heels will be predisposed to plantarflexion somatic dysfunctions because their foot is often in this position; to treat this patient with muscle energy, dorsiflexion will be utilized, moving further into the restrictive barrier with each iteration of treatment. |

HVLA techniques can be applied to somatic dysfunctions of the foot and ankle:

| Anterior tibia on talus somatic dysfunction HVLA: The patient is supine. The physician grasps the calcaneus with one hand and thrusts downward on the anterior tibia proximal to the ankle mortise toward the table. |  Anterior Tibia on Talus HVLA |

| Posterior tibia on talus somatic dysfunction HVLA: The patient is supine. The physician wraps their hands around the foot, interlacing the fingers on the dorsum with the thumbs on the ball of the foot. The foot is dorsiflexed to the restrictive barrier and a thrust is directed to increase dorsiflexion. |  Posterior Tibia on Talus HVLA |

| Cuneiform plantar somatic dysfunction (Hiss whip) HVLA: The patient is prone with the affected leg hanging off the table. The physician's hands are wrapped around the foot with the thumbs placed over the displaced cuneiform. A whip-like motion is performed with the thumbs thrusting downward into the sole of the foot. |  Cuneiform Plantar Dysfunction Hiss Whip HVLA |

| Fifth metatarsal plantar somatic dysfunction HVLA: The patient is supine. The physician stabilizes the patient's ankle with one hand and places the thumb of the other hand over the dorsal aspect at the distal end of the fifth metatarsal. The metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger is placed beneath the styloid process. A thrust is delivered by both fingers simultaneously. |  Fifth Metatarsal Plantar HVLA |

Counterstrain tenderpoints and treatments for selected lower extremity muscles:

| Tenderpoint+ | Location | Treatment position (initial setup) | Acronym | Figure (from Nicholas) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensor fasciae latae (Iliotibial band) | Along the IT band distal to the lateral trochanter | Hip/thigh is abducted and slightly flexed (may need slight IR/ER) | F Abd |  Lateral Trochanter IT band CS |

| Semimembranosus |

|

Knee is flexed and the tibia is internally rotated and abducted | F IR Add |  Semimembranosus CS |

| Popliteus | Belly of the popliteus muscle just inferior to the popliteal space | Patient prone; lateral ankle/foot used to control lower leg, knee is flexed and tibia is internally rotated | F IR |  Popliteus CS |

| Gastrocnemius | Proximal gastrocnemius muscles distal to the popliteal margin | Patient prone; knee is flexed and dorsum of the foot is placed on physician's thigh while physician applies compressive force on the calcaneus to produce marked plantar flexion of the ankle | F (knee), compress calcaneus inducing plantarflexion of ankle |  Extension Ankle Gastrocnemius CS |

| Tibialis anterior |

|

Lateral recumbent, a pillow is placed under the medial aspect of the distal tibia to create a fulcrum; an inversion force is applied to the foot and ankle with slight internal rotation | Inv IR |  Medial Ankle Tibialis Anterior CS |

| Fibularis (Peroneus) |

|

Lateral recumbent, a pillow under the lateral aspect of the distal tibia to create a fulcrum; an eversion force is applied to the foot and ankle with slight foot external rotation | Ev ER |  Lateral Ankle Fibularis CS |

| Quadratus plantae | Anterior aspect of calcaneus on plantar surface | Dorsiflexion | F |  Flexion Calcaneus Quadratus Plantae CS |

+ Tenderpoints can be found anywhere along the length of the muscle; these are the most common tenderpoint locations.

Soft tissue techniques can be used in the treatment of pes planus:

| Longitudinal arch springing: The patient is prone. Both of the physician's thumbs are placed under the longitudinal arch of the patient’s foot. The cephalad hand wraps laterally; the caudad hand wraps medially. The two hands twist in opposite directions in a wringing motion. This is repeated for 30 seconds. |  Longitudinal Arch Springing |

Myofascial release of the interosseous membrane can be performed for both the upper and lower extremities. The techniques are analogous and performed similarly:

| Interosseous membrane myofascial release: The physician palpates the lower leg over the interosseous membrane and assesses for restrictions in range of motion in the three planes of motion (superior and inferior, left and right translation, and clockwise and counterclockwise rotation). After determining the ease/bind asymmetry, treatment can be performed directly or indirectly for 30-60 seconds. |  Interosseous Membrane MFR Note: this photo is for the UPPER extremity; the lower extremity treatment is analogous |

Gait

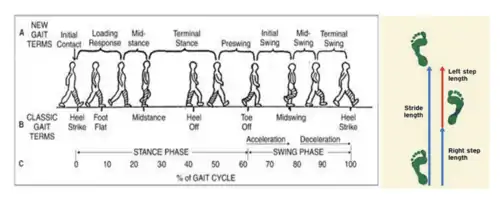

The bones of the spine and pelvis move in specific directions during the normal walking cycle, depending on which leg is moving forward. Dynamic motion of the sacrum and innominates occurs during walking. As weight bearing shifts to one leg, unilateral lumbar sidebending engages the ipsilateral oblique sacral axis by shifting weight to that sacroiliac joint. The sacrum now rotates forward on the opposite side, creating a deep sacral sulcus. With the next step, this process reverses as weight bearing changes to the other leg. The sacral base is constantly moving forward on one side, then the other, about the oblique axes. (Thus, physiologic somatic dysfunctions of the sacrum are named as such because these motions occur during the normal walking cycle.) As this occurs, the innominates are rotating in opposite directions to each other about the inferior transverse sacral axis (S4). One side rotates anteriorly as the other side rotates posteriorly. Summarizing: the anterior leg has a posterior innominate and an anterior sacral base with a deep sacral sulcus; the posterior leg has an anterior innominate and posterior inferior lateral angle. Figure 8.1 illustrates the gait cycle and reflects both new and classic terminology.

Figure 8.1 – Gait Cycle Terminology; graphical representation of stride and step lengths (source unknown)

The gait cycle is the sequence of functions of one limb. One gait cycle is equal to one stride, and one stride length is equal to two steps. The stance phase occurs when the limb is in contact with the ground. The swing phase occurs during limb advancement and limb clearance. The stance phase involves initial contact, loading response, mid-stance, terminal stance, and preswing. As walking speed increases, the stance phase decreases and the swing phase increases. Cadence describes the number of steps per unit time or distance.

During the loading response, weight shifts to the stance leg when the contralateral limb is lifting off the ground; this is where the lowest center of gravity is present. During the midstance phase, the ankles are aligned in the coronal plane; this is where the highest center of gravity is present. (The center of gravity is located 5 cm anteriorly to S2.) The terminal stance occurs after the midstance and just prior to the initial contact of the contralateral limb. During preswing, unloading of the ipsilateral limb occurs just prior to lift off. To permit the body to move forward on the right, trunk rotation in the thoracic area occurs to the left accompanied by lateral flexion to the left in the lumbar with movement of the lumbar vertebrae into the forming convexity to the right (the thoracic spine rotates left and the lumbar spine sidebends left and rotates right). There is a torsional locking at the lumbosacral junction on the left as the body of the sacrum is moving to the left, about a left oblique axis (L on L), thus shifting the weight of the body to the left foot to allow lifting of the right foot. The shifting vertical center of gravity moves to the superior pole of the left sacroiliac, locking the mechanism into mechanical position to establish movement of the sacrum on the left oblique axis which sets the pattern so the sacrum can torsionally turn to the left. The sacral base moves down (deep) on the right to conform to the lumbar C curve that is now formed to the right (lumbar spine is rotated right, convex right or sidebent left). The sacrum rotates in the opposite direction (to the left) of the lumbar spine (to the right). When the right foot moves forward, there is tensing of the right quadriceps and accumulating tension at the inferior pole of the right sacroiliac at the junction of the left oblique axis and the inferior transverse axis, which eventually locks as the weight swings forward allowing slight anterior movement of the right innominate on the inferior transverse axis. The movement is increased by the backward thrust of the restraining ground on the right leg.

The swing phase involves the initial swing, mid-swing, and the terminal swing phases. The initial swing involves lifting the limb off ground to maximum knee flexion. Tension on the hamstrings begins as the weight swings upward to the crest of the femoral support and there is a slight posterior movement of the right innominate on the inferior transverse axis. The movement is further increased by the weight of forward thrust of the propelling leg action. As the right heel strikes the ground, trunk torsion and accommodation begin to reverse themselves. As the left foot passes the right and weight passes over the crest of the femoral support, and accumulating force from above moves to the right, the sacrum changes its axis to the right oblique axis and the left sacral base moves forward towards the right around the right oblique axis. (R on R)

The mid-swing phase involves maximum knee flexion vertically to the tibia. During this phase, the left innominate moves from anterior rotation to posterior. The sacrum rotates rightward on a right oblique axis. The right anterior rotates anteriorly. (Summarizing, when the left leg is coming forward, the right innominate is anterior, the left innominate is posterior, and the sacrum is rotated right on a right oblique axis.) The terminal swing describes the vertical tibia position to just prior to initial contact. Double-limb support is present at the beginning and end of stance phase (20% of the gait cycle); single-limb support during swing phase (80% of the gait cycle). Running offers no double-limb support.

The six determinants of gait include:

- Pelvic rotation

- Pelvic tilt

- Lateral displacement of the pelvis

- Knee flexion in the stance phase

- Knee mechanisms

- Foot mechanisms

These determinants and any aberrations of them contribute to gait pathology.

- Gluteus medius gait (Trendelenburg gait) involves a shift of the body toward the deficient side, indicating a weakness of the gluteus medius muscle and can be identified by a positive Trendelenburg sign in the upright position.

- Gluteus maximus gait involves the trunk and pelvis being hyperextended backward over both hips to maintain the center of gravity behind the involved hip joint. A short lower extremity results in the pelvis and trunk being depressed in the stance phase.

- Waddling gait occurs due to an elevated pelvis gait occurs from a hiking or if elevation of the pelvis on the swing side if the hip or knee motion is limited. Congenital hip dislocation will manifest as a waddling gait.

- Osteoarthrosis gait occurs secondary to severe osteoarthrosis of the hip or knee joints and results in a “scissoring” gait. Any foot dysfunction may alter normal mechanics. These could include Morton's neuroma, corns, calluses, bunions, hallux rigidus, plantar warts, or poorly fitting shoes. If plantar flexion is absent, there is no push-off and the heel and forefoot come off the floor together.

- Hemiplegic gait: The affected leg is usually stiff, with loss of flexion at the hip and knee joints. The patient leans to the affected side and throws the whole leg outward from the body before bringing it back toward the trunk, producing a circumduction movement. The shoe is dragged against the floor, and there is usually an accompanying affected arm that does not swing but is held in fixed position against the abdomen with the elbow flexed.

- High-steppage gait: There are two patterns – the first pattern and the second pattern. In the first pattern, the toe touches the floor first, with a foot drop caused by paralysis of pretibial or peroneal muscles. The leg is raised high by abnormal knee and hip flexion. The toe touches the ground first, followed by a slapping noise as the foot strikes the floor. In the second pattern, the heel touches the floor first because of loss of sense of position. The high-steppage gait is bilateral, with ataxia and side-to-side reeling. The heel touches the floor first and a stomp of the foot is heard. Romberg sign is present, caused by a dysfunction of the afferent portion of peripheral nerves or posterior roots. Carcinoma, diabetic neuropathy, tabes dorsalis, Friedreich's ataxia, subacute combined degeneration of the cord, compression lesions of the posterior columns, and multiple sclerosis that affects the posterior columns may all produce a high-steppage gait.

- Shuffling gait: Shuffling gait is identified by small, flat-footed shuffling steps; the foot does not clear the ground. In Parkinsonism, rigidity, tremor, paucity of movement, shuffling with haste, and difficulty in starting, stopping, or turning are noted. The patient is in truncal flexion, with lack of extension movements at the hips, knees, and elbows. The thorax and pelvis rotate in the same direction in swing phase. The amplitude of vertical excursions of the head is lessened in forward motion. The first noticeable motor signs in Parkinsonism may be a non-rhythmic pattern with random or poorly timed activity of the arms in gait. Due to loss of confidence and equilibrium, the patient stands erect, takes small shuffling steps with a wide base, and seems to stare at a distant point. Turning is achieved through a series of small steps made by one foot, the other foot acting as a pivot.

- Ataxic gait: A reeling, unsteady gait with a wide base and a tendency to fall toward the side of the lesion. Vertigo may accompany ataxia. It may be found in cerebellar disease, multiple sclerosis, and sometimes myxedema. Ataxic gait must be differentiated from drunken and staggering gait, in which the subject reels, totters, tips forward and backward, and may lose balance and fall. This gait is seen in alcohol or barbiturate poisoning, drug reaction, polyneuritis, or general paresis.

- Scissors gait: The legs are adducted, crossing alternately in front of one another. Both lower limbs are spastic, and there is spasm of the adductor muscles at the hip joints, often accompanied by pronounced compensatory motions of the trunk and upper extremities. Bilateral upper motor neuron lesions, advanced cervical spondylosis, or multiple sclerosis may produce this gait pattern.

- Waddling gait: Rolling from side to side, the pelvic rotation and tilt on the swing side are increased (“penguin walk”). Muscular dystrophy with weakness of hips, exaggerated lordosis, and pot-bellied posture can produce this gait.

Review Questions

1. A patient presents complaining of right knee pain. On exam, an anterior force on the proximal tibia of the left leg showed anterior glide in comparison to that performed on the right leg. The test described is the ____ test with ____.

A. negative anterior drawer; no injury

B. positive anterior drawer; injury to the posterior cruciate ligament

C. positive anterior drawer; injury to the anterior cruciate ligament

D. negative posterior drawer; no injury

E. positive posterior drawer; injury to the anterior cruciate ligament

F. positive posterior drawer; injury to the posterior cruciate ligament

2. A patient presents complaining of right knee pain. On exam, restricted rotation of supination of the foot is observed. What additional observation would be expected for the proximal fibula?

A. Anterior restriction

B. Posterior restriction

C. Medial restriction

D. Lateral restriction

E. Pronation restriction

F. Supination restriction

3. A patient presents complaining of mid-foot pain that he describes as having a "pebble in his shoe". Somatic dysfunction of which bone of the foot is the likely cause of the problem?

A. The talus bone

B. The cuboid bone

C. The medial cuneiform bone

D. The lateral cuneiform bone

E. The navicular bone

4. A patient is found to have ease of motion of the ankle with anterior motion compared to posterior when performing the anterior and posterior drawer tests of the ankle. What is the somatic dysfunction diagnosis?

A. Anterior tibia on talus

B. Posterior tibia on talus

C. Anterior fibular head

D. Posterior fibular head

E. Talar fracture

5. What ligament protects the ankle from eversion sprains?

A. Plantar calcaneonavicular ligament

B. Anterior talofibular ligament

C. Calcaneofibular ligament

D. Posterior talofibular ligament

E. Deltoid ligament

6. When evaluating a patient's knee, they are noted to have a negative anterior and posterior drawer test, but exhibit tenderness along the proximal lateral lower leg. The patient is also noted to prefer inversion of the ankle. Which of the following describes the preferential motion of the patient’s lower extremity?

A. Anteromedial rotation of the fibula on the tibia

B. Anterolateral rotation of the fibula on the tibia

C. Posteromedial rotation of the fibula on the tibia

D. Posterolateral rotation of the fibula on the tibia

7. A patient presents for evaluation of low back, foot and ankle pain. She states that she wears five-inch high heels on an almost daily basis. Which of the following muscles would likely be hypertonic?

A. Gastrocnemius

B. Tibialis anterior

C. Rectus femoris

D. Fibularis longus

E. Plantaris

8. Which of the following is equivalent to two steps?

A. 1 gait cycle

B. 1 stride

C. 1/2 gait cycle and 1/2 stride

D. 2 strides

E. 1 gait cycle and 1 stride

9. What is the distance measured between two points of contact?

A. Stance length

B. Stance width

C. Step length

D. Step width

E. Stride length

F. Stride width

10. Which of the following best describes the initial setup for the treatment of a plantarflexion somatic dysfunction using post-isometric muscle energy?

A. The patient lies lateral recumbent with a pillow placed under medial aspect of the distal tibia to create a fulcrum; an inversion force is applied to the foot/ankle with slight internal rotation

B. The patient is prone while the lateral ankle/foot is used to control the lower leg and the knee is flexed and the tibia is internally rotated

C. The knee is flexed and the dorsum of the foot is placed on the physician's thigh while the physician applies a compressive force on the calcaneus to produce marked flexion

D. The patient lies in the lateral recumbent position with a pillow under the lateral aspect of the distal tibia to create a fulcrum while an eversion force is applied to the foot and ankle with slight external rotation of the foot

11. Which of the following correctly pairs the motions of the foot and the ankle?

A. Dorsiflexion, supination, inversion

B. Dorsiflexion, supination, eversion

C. Dorsiflexion, pronation, inversion

D. Plantarflexion, supination, eversion

E. Plantarflexion, pronation, inversion

F. Plantarflexion, supination, inversion

12. A 75-year-old female presents for evaluation of left back and knee pain after falling in her kitchen 3 days ago after washing her floor at home. She denies any other history of trauma or injury. She denies bladder or bowel incontinence, saddle anesthesia, or lower extremity paresthesias. Vital signs are stable and afebrile. On exam, she is found to have a hypertonic left piriformis and a right fibular head restricted in posterior glide compared to the left. A positive valgus test would indicate a tearing of which structure?

A. Lateral meniscus

B. Lateral collateral ligament

C. Medial meniscus

D. Medial collateral ligament

Answers to Review Questions

- C

- F

- B

- A

- E

- D

- A

- E

- E

- C

- F

- D