Chapter 1: Introduction to Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine

Objectives:

- Identify the four tenets of osteopathic medicine

- Describe active and passive motion

- Describe anatomic, physiologic, and restrictive barriers in the context of active and passive range of motion

- Define somatic dysfunction and distinguish between acute versus chronic dysfunctions

- Define planes of the body and the motions that occur in each plane and the axis used

- Define anatomical position

- Define terms of position and terms of motion to describe body structures

Osteopathic Concepts and Principles

The Four Principles of Osteopathic Medicine are:

- The body is a unit; the person is a unit of mind, body, and spirit.

- The body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance.

- Structure and function are reciprocally interrelated.

- Rational treatment is based upon an understanding of the basic principles of body unity, self-regulation, and the interrelationship of structure and function.

There are five treatment models which Osteopathic Medicine is based upon and derived from the Four Principles as detailed above:

- The biomechanical model considers how changes in structure lead to changes in function.

- The respiratory/circulatory model evaluates the movement of fluids from intracellular and extracellular compartments such as blood and lymphatic fluids.

- The neurologic model examines the effects of the autonomic nervous system on organ system.

- The metabolic energy model refers to the ability to perform physical activity.

- The behavior model surveys behavioral aspects that have a direct impact on health and well-being.

Motion and Barriers

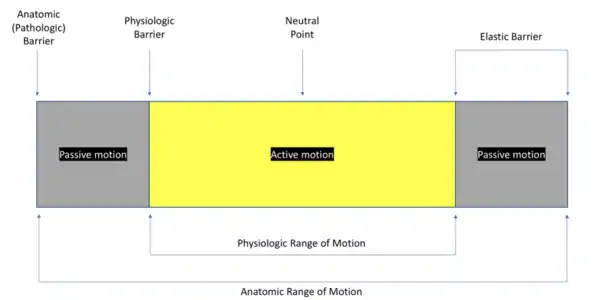

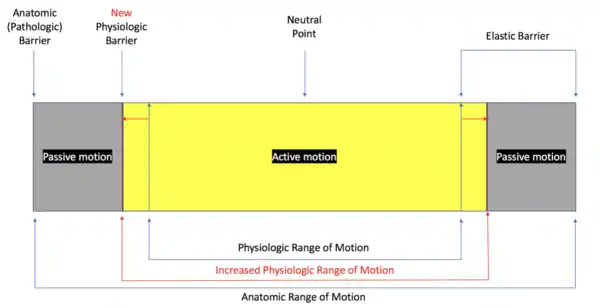

A motion is an act or process of a body changing position in terms of direction, course, and velocity. Motion can be described in terms of active motion, passive motion, and restricted motion. Active motion is produced voluntarily by a patient within a range of physiologic barriers. Passive motion is produced by an outside force without the assistance of the patient. Passive motion is induced by the physician while the patient remains passive or relaxed and is limited by the anatomic barrier. Figure 1.1 illustrates unrestricted motion. A barrier is a factor that restricts or limits motion. Barriers to normal motion include the physiologic barrier and anatomic barrier. The physiologic barrier is the extent to which a joint may be moved. Soft tissue tension will gradually accumulate to the point where voluntary movement becomes limited. The physiologic barrier is fluid in that it may be expanded to allow for greater range of motion by, for example, warm-up exercises. (Figure 1.2) The anatomic barrier is defined and limited by bone and ligaments which serve as the end-point of passive motion. Damage (i.e. trauma) is caused if motion occurs beyond the anatomic barrier. The anatomic barrier is the absolute limit imposed by the anatomic structure of a joint. As with the physiologic barrier, a gradual increase in resistance is produced by the soft tissues of the joint structure which limits the degree of passive motion as the anatomic barrier is approached. Proceeding beyond this barrier leads to injury and disrupts the anatomic structures of the joint. Inherent motion is activity which is unconsciously generated within the body and can be perceived at 1 micron (1 um) of distance. Inherent motion will be discussed more with osteopathic medicine in the cranial field.

Motion loss can be major or minor in severity; osteopathic physicians focus on minor motion loss which requires palpatory perception. The end feel is palpated as increasing resistance in the passive range of motion (PROM) as the physician approaches the anatomic barrier. It is tension that increases far more rapidly between the physiologic barrier and the anatomic barrier. As motion continues between the anatomic and physiologic barriers, the end feel indicates the endpoint of motion.

Restricted motion may be general, regional, or segmental. General motion may be observed as a patient walks, sits, stands up from a seated position, or other gross motions. Regional motion affects large areas of the body during specific movements. For example, the cervical spine can be assessed by asking a patient to touch their chin to their chest or to lean their head back. Segmental motion refers to the motion testing of a joint. Specific examples of segmental motion include flexion, extension, sidebending, rotation, abduction (or external rotation), and adduction (or internal rotation). Most joints have primary freedom in one plane of motion with limited or no movement in other planes; the shoulder and hip are exceptions to this. There is a trade-off between joint stability and range of motion.

Pathology in minor motion loss manifests as restricted motion which occurs as a physician attempts to move a patient through a passive range of motion of a joint and the motion stops abruptly. There is no end feel nor ligamentous resistance. Neither the anatomic nor physiologic barrier is reached. (Figure 1.3) The end result of minor motion loss is somatic dysfunction, which is the basis of osteopathic manipulative treatment. The restrictive barrier is the new barrier created as a result of a somatic dysfunction.

Somatic Dysfunction

Somatic dysfunction is defined as the impaired or altered function of related components of the somatic (i.e. body framework) system: skeletal, arthrodial, and myofascial structures as well as related vascular, lymphatic, and neural elements.

The four characteristics of somatic dysfunction are identified by TART:

- T = tenderness

- A = asymmetry

- R = restriction in range of motion

- T = tissue texture changes

These findings are present with all types of somatic dysfunction, regardless of the cause or duration of time which they are present. Only one TART finding is needed to diagnose a somatic dysfunction.

Somatic dysfunctions can be classified as acute or chronic in nature:

| Acute somatic dysfunction | Chronic somatic dysfunction |

|---|---|

On light-to-firm touch:

|

On light-to-firm touch:

|

On deep palpation:

|

On deep palpation:

|

Table 1.1: Acute versus chronic somatic dysfunction findings

Acute somatic dysfunctions are characterized by immediate or short-term impairment and altered function of the somatic system associated with vasodilation, leading to edema, heat, and redness. Chronic somatic dysfunctions are characterized by long-term impairment (>6 months) and associated with fibrosis, ropy changes, pruritus, paresthesias (numbness or sensory loss), contractures (joints which cannot move from a fixed position), and cold.

Somatic dysfunction is treatable using osteopathic manipulative treatment. The positional and motion aspects of somatic dysfunction are best described using at least one of three parameters:

- The position of a body part as determined by palpation and referenced to its adjacent defined structure.

- The direction(s) in which motion is freer. (This is how somatic dysfunctions are named.)

- The direction(s) in which motion is restricted.

| Example: Naming a somatic dysfunction |

|---|

| If C3 is restricted in the extended position and with right sidebending and right rotation, then the somatic dysfunction is named as a C3 flexion dysfunction which is rotated left and sidebent left (written as C3 FRLSL). |

Palpation and Planes of Movement

Palpation is defined as the application of variable manual pressure to the surface of the body for the purpose of determining shape, size, consistency, position, inherent motility, and health of tissues underneath the skin. The pads of the fingers have more touch nerve endings than anywhere else in the hand. The thumb and the first two finger pads are the most sensitive part of the hand to train and use for palpation. (Do not use the fingertips.) Palpation can be used to appreciate position and movement.

| Plane | A plane describes an imaginary flat surface running through the body. Movement occurs in three planes of motion:

|

|---|---|

| Axis | An axis is an imaginary line at right angles about which the body rotates or spins. Motion of a joint occurs about an axis. There are three axes of rotation:

|

It is imperative to become proficient in the terms related to position and motion.

Terms related to position:

- Medial: structure situated near the median sagittal plane

- Lateral: structure situated away from the median sagittal plane

- Anterior (Ventral): structure situated on the front surface of the body

- Posterior (Dorsal): structure situated on the back surface of the body

- Proximal: a relative measurement of a structure closer to the center of the body

- Distal: a relative measurement of a structure farther away from the center of the body

- Superficial: close to the surface of the body

- Deep: further from the surface of the body

- Superior: closer to the top of the body

- Inferior: closer to the bottom of the body

- Cephalad/Cranial: closer to the head of the body

- Caudad: closer to the “tail” of the body

- Ipsilateral: two structures on the same side of the body

- Contralateral: two structures on opposite sides of the body

- Prone: lying face down

- Supine: lying face up

- Lateral recumbent: lying on the side (can be left or right)

Terms related to movement:

- Flexion: forward motion in sagittal plane about transverse axis; shortening a curve

- Extension: backward motion in sagittal plane about transverse axis; straighten a curve

- Sidebending: also lateral flexion; movement in the coronal plane around sagittal axis

- Rotation: movement of a part of the body around a long axis

- Abduction: also called external rotation; motion away from the midline of the body in the coronal plane; called depression if the shoulder is brought downward away from the head

- Adduction: also called internal rotation; motion toward the midline of the body in the coronal plane; called elevation if the shoulder is brought upward toward the head

- Note: With motion of the fingers and the toes, abduction and adduction refers to the spreading apart and drawing together, respectively, of these structures.

- Circumduction: combination in sequence of movements of flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction in a circular motion (for example, of the shoulder or of the hip girdle)

- Pronation: medial rotation of the forearm such that palm of the hand faces posteriorly

- Supination: lateral rotation of the forearm such that palm of the hand faces anteriorly

- Inversion: movement of the foot at the ankle joint so the sole of foot faces in medially

- Eversion: movement of the foot at the ankle joint so the sole of foot faces in laterally

Palpation and Planes of Movement

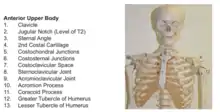

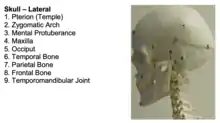

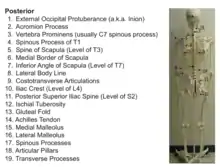

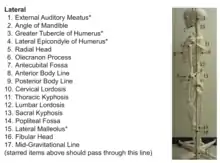

It is important to have a working knowledge of anatomic landmarks in order to palpate and diagnose somatic dysfunctions. The following figures illustrate important anatomic landmarks:

Anterior Upper Body |

Anterior Pelvis |

Skull - Anterior |

Skull - Lateral |

Posterior |

Lateral |

Photo credits: Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine Department of Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine

Landmarks of the back include the mid-spinal line, the paravertebral line, and the line of the angle of the ribs: The mid-spinal line overlies the spinous processes of the vertebrae from the middle of the sub-occipital region below the inion to the tip of the coccyx. The paravertebral line extends the entire length of the spine and corresponds to the tips of the transverse processes. In the cervical spine, this is approximately 1 inch away from the transverse processes; in the thoracic spine, this is approximately 1 ½ inches away from the transverse processes. Additional landmarks include the sacral sulcus, which is the distance between the sacral base and the PSIS at either sacroiliac joint. This area, along with the inferior lateral angle of the sacrum, is very useful for making diagnoses on the sacral region (more on this in subsequent chapters).

The Osteopathic Structural Exam

The Osteopathic Structural Exam involves assessing static symmetry, gait, extremities, and segmental examination of the vertebrae among other special tests which will be discussed within the context of each body region. It is not standardized and varies from patient to patient. The first and most important step, however, is observation of a patient. The physician should note the posture of the patient while remaining still (static posture) and while moving (dynamic posture). Function and range of motion should be assessed both actively and passively. The physician should look for asymmetries and abnormalities prior to the palpatory exam.

The components of the osteopathic structural exam include:

- Static symmetry

- Gait

- Seated cervical spine exam

- Seated thoracic spine exam

- Hip drop test

- Standing flexion test

- Seated flexion test

- FABERE test

- Upper extremity

- Lower extremity

- Segmental evaluation

In order to assess static symmetry, a patient should be standing comfortably on a level surface with their shoes off and their extremities should be in full extension with palms facing outward with the physician standing far enough away to view the entire body. This is known as anatomic position. For example, in anatomic position, the upper extremity has the shoulders adducted, the elbows extended, and the wrist (and, by extension, the hand) supinated.

The patient should be examined from anterior, posterior, and sagittal views in order to assess for asymmetry. The mid-gravitational line is an imaginary line used during the osteopathic structural exam to assess for somatic dysfunction and should pass through the following five structures in the sagittal view:

- external auditory meatus

- greater tubercle of the humerus

- lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- the greater trochanter of the femur

- lateral malleolus

With regard to spinal regions, the anatomic position of:

- the cervical spine is lordotic (or convex in)

- the thoracic spine is kyphotic (or convex out)

- the lumbar spine is lordotic, and

- the sacral spine is kyphotic

Gait will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

| The seated cervical exam assesses active and passive ranges of motion of the cervical spine. The patient is seated on exam table facing the physician. Flexion and extension, sidebending (to each side), and rotation (to each side) of the cervical spine are performed by asking the patient to touch their chin to their chest (flexion) and then lean their head back. Next, they are asked to turn their head to the left without moving the chin and to the right in the same fashion to assess rotation. Lastly, they are asked to touch their respective ear to their respective shoulder without making contact to assess sidebending. At the end of each of these motions, the physician can passively move the patient further in the direction being tested. This allows for testing of active range of motion and passive range of motion simultaneously and can also be useful in identifying restrictions and somatic dysfunction. |  Seated cervical exam |

| The seated thoracic exam is carried out in a similar fashion. Assessing passive range of motion requires a bit more of physician involvement. With respect to sidebending, for the upper levels (T1-T3), the physician’s hands are placed bilaterally as close to the root of the neck as possible and pressure is applied. To assess the middle levels (T4-T8), the hands are placed on the shoulders and downward and medial pressure is applied once again. Rotation assesses the lowest levels of the thoracic spine (T9-T12) by the physician’s hands being placed on the shoulders and rotated one at a time to the left and right. |  Seated thoracic exam |

| The hip drop test assesses lumbar sidebending and is performed by asking the patient to stand with their feet 4 to 6 inches apart. The physician’s hands are placed on the top of the iliac crests. The patient is instructed to flex one knee and carry their body weight on the opposite side. The opposite side is then tested. The hip that drops the least is the restricted side, showing a restriction in lumbar sidebending to that side and an ease of rotation to the same side. For example, if the left side shows decreased hip drop (a positive test), then the left side is the side of rotation dysfunction. Since multiple levels are being tested by this test, Fryette’s first law applies and a diagnosis can be made, for example, of L2-L4 NSRRL. (More on Fryette’s Laws in Chapter 4.) |  Hip Drop Test |

| The standing flexion test lateralizes somatic dysfunction of iliosacral motion. The patient stands with their knees extended and feet apart at a distance equivalent to the positions of the acetabulum. The physician sits behind the patient with eyes at the level of the patient’s posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The patient is asked to bend forward slowly without flexing their knees. During the bending motion, the physician will observe anterosuperior excursion of thumbs on the patient’s PSIS and note if one side moves further than the other. The side that moves first and moves the furthest is the positive side, indicating iliosacral restriction of the ipsilateral side. The SI (sacroiliac) compression test (or ASIS compression test) is done with the patient in a supine position. The physician places their palms bilaterally over the patient’s anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). The physician then presses posteriorly and laterally. The test is positive on the side with a lack of motion. Both the standing flexion test and the SI compression test can be used to diagnose innominate and sacral somatic dysfunctions. |  Standing flexion test |

| The seated flexion test is performed to also determine laterality of sacroiliac dysfunction. It is done by having the patient seated on the exam table with the knees flexed to 90 degrees. The physician sits behind the patient with the eyes at the level of the pelvis and the thumbs on the PSIS. The patient is asked to bend forward. Ideally, the patient’s feet should be in contact with the ground while performing this test to avoid injury to the patient. As with the standing flexion test, the side that moves first and moves the furthest is the positive side, indicating sacroiliac restriction on the ipsilateral side. |  Seated flexion test |

| Patrick’s test (also known as FABERE test) is used to differentiate between hip and sacroiliac somatic dysfunction. FABERE is actually an acronym for the motions assessed for the hip joint: Flexion, ABduction, External Rotation, and Extension. With the patient supine, the foot is placed on the opposite knee. The hip is then brought through flexion, abduction, external rotation, and extension. If there is inguinal pain, there may be hip dysfunction present. When the endpoint of the test is reached, the femur is flexed in relation to the pelvis. To stress the sacroiliac joint, extend the range of motion by placing one hand on the knee and the other hand on the contralateral ASIS. Press down gently on each of these points. If the patient complains of increased pain, there may be somatic dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint. |  FABERE test |

The primary goal of the standing flexion test and the seated flexion test is to lateralize sacroiliac joint motion restriction. The standing flexion test is more attuned to motion of the ilia on the sacrum (iliosacral motion) and is used to assess innominate somatic dysfunction. The seated flexion test is better suited to assess the motion of the sacrum between the ilia (sacroiliac motion) and is used to assess sacral somatic dysfunction. In the event that both the standing flexion test and seated flexion tests are positive on the same side, there is likely a sacral dysfunction present. If only the standing flexion test yields a positive result and the seated flexion test does not show lateralization, there is likely an innominate dysfunction. These topics will be covered in the more detail in forthcoming chapters.

Segmental evaluation involves the patient standing on a level surface with their shoes off in anatomic position. The physician’s eyes are kept at the level of the body part being examined with light palpation used to confirm observations:

Anterior view:

|

Posterior view:

|

Sagittal view:

|

Fascia

Fascia is a sheet of fibrous tissue that envelopes the body beneath the skin. It also encloses muscles and groups of muscles, separating their several layers or groups. Fascia supports and stabilizes the body, helping to maintain balance and posture. It assists in the production and control of motion and the interrelation of motion of related parts. The superficial fascia functions to pad and provide heat conservation. It allows for sliding of structures. It includes adipose tissue and serves as loose connective tissue in a framework of interwoven collagen fibers intermingled with occasional elastic fibers. Aponeuroses serve as thin wide tendons which serve as attachments for muscle and bones. For example, consider the abdominal aponeurosis. The deep fascia is the thin, often shiny layer adherent to muscles. Can also be observed as a tough fibrous layer to which many muscles attach. It is continuous with the periosteum of the bone and in the limbs forms compartments. For example, the iliotibial band transmits the pull of the tensor fasciae latae and some of the gluteus maximus to the femur and the tibia.

At the base of the skull, the dura mater becomes continuous with the extracranial fascia and becomes subject to tensions arising outside of the skull. The fascia at the base of the skull is in direct continuity with the fascia from the apex of the respiratory diaphragm. This fascia is continuous with the fascia that extends throughout the body. Fascia is comprised of fibers made of collagen and elastin. Collagen is one of the most widely distributed and abundant proteins in the body which possesses a high tensile strength but are usually flexible. Elastin can be stretched and returned to its original position. Ground substance varies from thin gel to bone, is hydrophilic and either have slow movement or rapid abrupt movement. Cartilage is present in between the mineralized salts of the connective tissue and the ground substance.

Fascia will change under pressure and heat and will also change depending on the environment and needs of the body; it is plastic in that it has the ability to retain a shape attained by deformation and elastic in that it has the ability to return to its original shape after undergoing deformation. The dynamic relationship between fascia, muscles, bones, and gravity creates posture. Changes in posture will create changes in the bony architecture. Fascial tension can decrease blood and lymphatic flow and affect neural transmissions.

Fascia has properties similar to bone. Collagen has bioelectric resting potentials and stress-generated action potentials. Electrical currents are miniscule and piezoelectric, during which electrical energy is converted into mechanical energy and mechanical energy is converted to electrical energy. Areas of compression become electronegative and areas of distraction become electropositive, creating an electric field. The implication of this is that palpation generates mechanical and electrical energy. Patterns of fascial stress can be determined by palpation, and treatments can be direct or indirect in nature.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following represents the absolute end-range of motion?

A. Anatomic barrier

B. Physiologic barrier

C. Restrictive barrier

D. Active barrier

E. Passive barrier

2. Which of the following ranges of motion is matched properly with its barrier?

A. Passive range of motion :: Physiologic barrier

B. Passive range of motion :: Restrictive barrier

C. Active range of motion :: Anatomic barrier

D. Active range of motion :: Restrictive barrier

E.Passive range of motion :: Anatomic barrier

3. Which of the following correctly defines the physiologic barrier?

A. The end of motion which a patient can move voluntarily

B. The end of motion which a patient can move involuntarily

C. Motion loss that occurs as a result of somatic dysfunction

D. Resistance that increases as the motion endpoint is reached

E. Motion that can be decreased by performing warm-up exercises

4. Restricted motion can occur with which of the following?

A. General motion

B. Regional motion

C. Segmental motion

D. All of the above

E. None of the above

5. Somatic dysfunction affects all of the following except:

A. skeletal structures (i.e. bones)

B. lymphatic structures

C. myofascial structures (i.e. muscles)

D. vascular structures (i.e. arteries and veins)

E. organ structures

6. Somatic dysfunctions are classified by all of the following characteristics except:

A. tenderness

B. temperature changes

C. asymmetry

D. restricted active or passive range of motion

E. tissue texture changes

7. Which of the following findings is not properly paired?

A. acute somatic dysfunction :: edema

B. acute somatic dysfunction :: tenderness

C. acute somatic dysfunction :: fibrotic changes

D. chronic somatic dysfunction :: cool to the touch

E. chronic somatic dysfunction :: decreased range of motion

8. Somatic dysfunctions are named based on the direction in which the palpated structure is ____. If C3 is restricted in the extended position with right sidebending and right rotation, then the somatic dysfunction is written ____.

A. restricted; C3 FRLSL

B. freer; C3 ERRSR

C. freer; C3 ERLSL

D. restricted; C3 ERRSR

E. freer; C3 FRLSL

9. Restriction in rotation of the thoracic spine at the level of T4-T6 is an example of ____ motion loss. Restriction of sidebending in the lumbar spine is an example of ____ motion loss.

A. regional; regional

B. regional; segmental

C. segmental; segmental

D. segmental; regional

E. general; general

10. Extension, rotation, and sidebending occur in the ____, ____, and ____ planes, respectively.

A. sagittal; transverse; coronal

B. sagittal; coronal; transverse

C. coronal; sagittal; transverse

D. coronal; transverse; sagittal

E. transverse; sagittal; coronal

11. Lateral flexion is synonymous with which of the following terms?

A. Translation

B. Sidebending

C. Rotation

D. Circumduction

E. Eversion

12. Flexion of the elbow occurs in the ____ plane around a ____ axis.

A. sagittal; transverse

B. sagittal; anteroposterior

C. coronal; transverse

D. coronal; vertical

E. sagittal; vertical

Questions 13-19: For the following, match the anatomic landmark with the corresponding spinal level.

A. C7

B. T2

C. T3

D. T7

E. T10

F. L4

G. S2

13. Posterior superior iliac spine

14. Jugular notch

15. Inferior angle of the scapula

16. Iliac crest

17. Spine of the scapula

18. Vertebra prominens

19. Umbilicus

20. Which of the following is true regarding the Osteopathic Structural Exam?

A. The Osteopathic Structural Exam is a standardized exam

B. The Osteopathic Structural Exam does not require observation of the patient

C. The Osteopathic Structural Exam varies from physician to physician

D. The Osteopathic Structural Exam should only involve static observations

E. The Osteopathic Structural Exam should only involve dynamic observations

21. Anatomic position of the upper extremity has the shoulders ____, the elbows ____, and the wrist ____.

A. adducted; extended; pronated

B. adducted; flexed; supinated

C. abducted; extended; supinated

D. abducted; flexed; pronated

E. adducted; extended; supinated

22. Which of the following structures passes through the mid-gravitational line?

A. External auditory meatus

B. Lesser tubercle of the humerus

C. Medial epicondyle of the humerus

D. Lesser trochanter of the femur

E. Medial malleolus

23. Which of the following is not one of the Four Principles of Osteopathic Medicine?

A. Rational treatment is based upon an understanding of the basic principles of body unity, self-regulation, and the interrelationship of structure and function.

B. Structure and function are reciprocally interrelated.

C. The movement of the sacrum between the ilia is involuntary.

D. The body is a unit; the person is a unit of mind, body, and spirit.

E. The body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance.

24. Which of the following osteopathic treatment models is incorrectly defined?

A. The biomechanical model considers how changes in function lead to changes in structure.

B. The respiratory/circulatory model evaluates the movement of fluids from intracellular and extracellular compartments such as blood and lymphatic fluids.

C. The neurologic model examines the effects of the autonomic nervous system on organ system.

D. The metabolic energy model refers to the ability to perform physical activity.

E. The behavior model surveys behavioral aspects that have a direct impact on health and well-being.

25. Somatic dysfunction is named by _____.

A. Active range of motion

B. Passive range of motion

C. Ease of motion

D. Restriction of motion

E. Tissue texture changes

Answers to Review Questions

- A

- E

- A

- D

- E

- B

- C

- E

- D

- A

- B

- A

- G

- B

- D

- F

- C

- A

- E

- C

- C

- A

- C

- A

- C