Clock gating

In computer architecture, clock gating is a popular power management technique used in many synchronous circuits for reducing dynamic power dissipation, by removing the clock signal when the circuit is not in use or ignores clock signal. Clock gating saves power by pruning the clock tree, at the cost of adding more logic to a circuit. Pruning the clock disables portions of the circuitry so that the flip-flops in them do not have to switch states. Switching states consumes power. When not being switched, the switching power consumption goes to zero, and only leakage currents are incurred.[1]

Although asynchronous circuits by definition do not have a global "clock", the term perfect clock gating is used to illustrate how various clock gating techniques are simply approximations of the data-dependent behavior exhibited by asynchronous circuitry. As the granularity on which one gates the clock of a synchronous circuit approaches zero, the power consumption of that circuit approaches that of an asynchronous circuit: the circuit only generates logic transitions when it is actively computing.[2]

Details

An alternative solution to clock gating is to use Clock Enable (CE) logic on synchronous data path employing the input multiplexer, e.g., for D type flip-flops: using C / Verilog language notation: Dff= CE? D: Q; where: Dff is D-input of D-type flip-flop, D is module information input (without CE input), Q is D-type flip-flop output. This type of clock gating is race condition free and is preferred for FPGAs designs and for clock gating of the small circuit. For FPGAs every D-type flip-flop has an additional CE input signal.

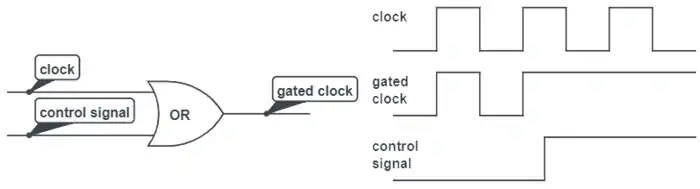

Clock gating works by taking the enable conditions attached to registers, and uses them to gate the clocks. A design must contain these enable conditions in order to use and benefit from clock gating. This clock gating process can also save significant die area as well as power, since it removes large numbers of muxes and replaces them with clock gating logic. This clock gating logic is generally in the form of "integrated clock gating" (ICG) cells. However, the clock gating logic will change the clock tree structure, since the clock gating logic will sit in the clock tree.

Clock gating logic can be added into a design in a variety of ways:

- Coded into the register transfer level (RTL) code as enable conditions that can be automatically translated into clock gating logic by synthesis tools (fine grain clock gating).

- Inserted into the design manually by the RTL designers (typically as module level clock gating) by instantiating library specific integrated clock gating (ICG) cells to gate the clocks of specific modules or registers.

- Semi-automatically inserted into the RTL by automated clock gating tools. These tools either insert ICG cells into the RTL, or add enable conditions into the RTL code. These typically also offer sequential clock gating optimisations.

Any RTL modifications to improve clock gating will result in functional changes to the design (since the registers will now hold different values) which need to be verified.

Sequential clock gating is the process of extracting/propagating the enable conditions to the upstream/downstream sequential elements, so that additional registers can be clock gated.

Chips intended to run on batteries or with very low power such as those used in the mobile phones, wearable devices, etc. would implement several forms of clock gating together. At one end is the manual gating of clocks by software, where a driver enables or disables the various clocks used by a given idle controller. On the other end is automatic clock gating, where the hardware can be told to detect whether there's any work to do, and turn off a given clock if it is not needed. These forms interact with each other and may be part of the same enable tree. For example, an internal bridge or bus might use automatic gating so that it is gated off until the CPU or a DMA engine needs to use it, while several of the peripherals on that bus might be permanently gated off if they are unused on that board.

References

- Panda, Preeti Ranjan; Shrivastava, Aviral; v. n. Silpa, B.; Gummidipudi, Krishnaiah (2010-09-17). Power-efficient System Design (1 ed.). Springer. pp. 25, 73. ISBN 978-1-4419-6387-1.

- Hübner, Michael; Becker, Jürgen (2010-12-03). Multiprocessor System-on-Chip: Hardware Design and Tool Integration (1 ed.). Springer. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4419-6459-5.

Further reading

- Li, Hai; Bhunia, S. (2003-02-28) [2003-02-12]. "Deterministic clock gating for microprocessor power reduction". The Ninth International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture, 2003. HPCA-9 2003. Proceedings. IEEE. pp. 113–122. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.79.6234. doi:10.1109/HPCA.2003.1183529. ISBN 978-0-7695-1871-8. ISSN 1530-0897. S2CID 6304290.