Perceptron

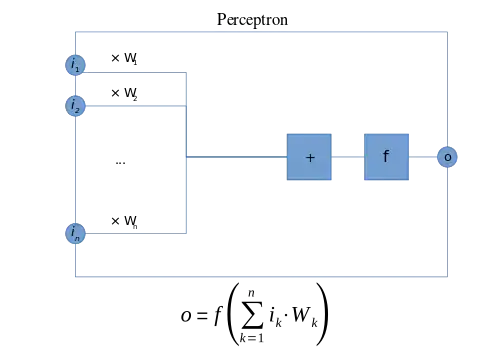

In machine learning, the perceptron (or McCulloch-Pitts neuron) is an algorithm for supervised learning of binary classifiers. A binary classifier is a function which can decide whether or not an input, represented by a vector of numbers, belongs to some specific class.[1] It is a type of linear classifier, i.e. a classification algorithm that makes its predictions based on a linear predictor function combining a set of weights with the feature vector.

| Part of a series on |

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

History

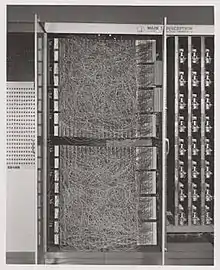

The perceptron was invented in 1943 by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts.[3] The first implementation was a machine built in 1957 at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory by Frank Rosenblatt,[4] funded by the United States Office of Naval Research.[5]

_(20897323365).jpg.webp)

The perceptron was intended to be a machine, rather than a program, and while its first implementation was in software for the IBM 704, it was subsequently implemented in custom-built hardware as the "Mark 1 perceptron". This machine was designed for image recognition: it had an array of 400 photocells arranged in a 20x20 grid, randomly connected to 512 "association units" to "eliminate any particular intentional bias in the perceptron". The association units then correct to response units, with adjustable weights were encoded in potentiometers, and weight updates during learning were performed by electric motors.[2]: 193 The hardware details are in an operators' manual.[6]

In a 1958 press conference organized by the US Navy, Rosenblatt made statements about the perceptron that caused a heated controversy among the fledgling AI community; based on Rosenblatt's statements, The New York Times reported the perceptron to be "the embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence."[5]

Although the perceptron initially seemed promising, it was quickly proved that perceptrons could not be trained to recognise many classes of patterns. This caused the field of neural network research to stagnate for many years, before it was recognised that a feedforward neural network with two or more layers (also called a multilayer perceptron) had greater processing power than perceptrons with one layer (also called a single-layer perceptron).

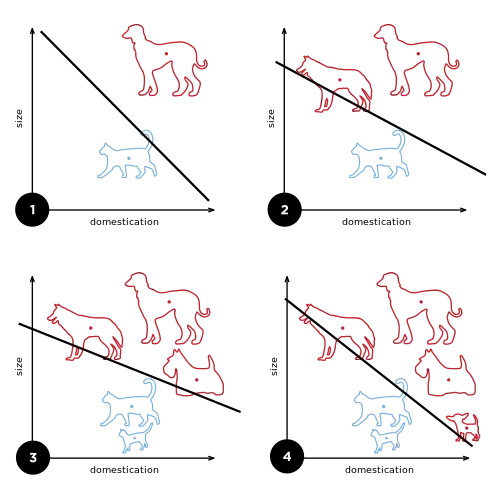

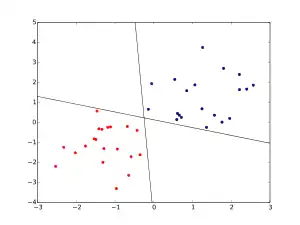

Single-layer perceptrons are only capable of learning linearly separable patterns.[7] For a classification task with some step activation function, a single node will have a single line dividing the data points forming the patterns. More nodes can create more dividing lines, but those lines must somehow be combined to form more complex classifications. A second layer of perceptrons, or even linear nodes, are sufficient to solve many otherwise non-separable problems.

In 1969, a famous book entitled Perceptrons by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert showed that it was impossible for these classes of network to learn an XOR function. It is often believed (incorrectly) that they also conjectured that a similar result would hold for a multi-layer perceptron network. However, this is not true, as both Minsky and Papert already knew that multi-layer perceptrons were capable of producing an XOR function. (See the page on Perceptrons (book) for more information.) Nevertheless, the often-miscited Minsky/Papert text caused a significant decline in interest and funding of neural network research. It took ten more years until neural network research experienced a resurgence in the 1980s.[7] This text was reprinted in 1987 as "Perceptrons - Expanded Edition" where some errors in the original text are shown and corrected.

A 2022 article states that the Mark 1 Perceptron was "part of a previously secret four-year NPIC [the US' National Photographic Interpretation Center] effort from 1963 through 1966 to develop this algorithm into a useful tool for photo-interpreters".[8]

The kernel perceptron algorithm was already introduced in 1964 by Aizerman et al.[9] Margin bounds guarantees were given for the Perceptron algorithm in the general non-separable case first by Freund and Schapire (1998),[1] and more recently by Mohri and Rostamizadeh (2013) who extend previous results and give new L1 bounds.[10]

The perceptron is a simplified model of a biological neuron. While the complexity of biological neuron models is often required to fully understand neural behavior, research suggests a perceptron-like linear model can produce some behavior seen in real neurons.[11]

Definition

In the modern sense, the perceptron is an algorithm for learning a binary classifier called a threshold function: a function that maps its input (a real-valued vector) to an output value (a single binary value):

where is a vector of real-valued weights, is the dot product , where m is the number of inputs to the perceptron, and b is the bias. The bias shifts the decision boundary away from the origin and does not depend on any input value.

The value of (0 or 1) is used to classify as either a positive or a negative instance, in the case of a binary classification problem. If b is negative, then the weighted combination of inputs must produce a positive value greater than in order to push the classifier neuron over the 0 threshold. Spatially, the bias alters the position (though not the orientation) of the decision boundary. The perceptron learning algorithm does not terminate if the learning set is not linearly separable. If the vectors are not linearly separable learning will never reach a point where all vectors are classified properly. The most famous example of the perceptron's inability to solve problems with linearly nonseparable vectors is the Boolean exclusive-or problem. The solution spaces of decision boundaries for all binary functions and learning behaviors are studied in the reference.[12]

Rosenblatt described the details of the perceptron in a 1958 paper.[13] His organization of a perceptron is constructed of three kinds of cells ("units"): AI, AII, R, which stand for "projection", "association" and "response".

In the context of neural networks, a perceptron is an artificial neuron using the Heaviside step function as the activation function. The perceptron algorithm is also termed the single-layer perceptron, to distinguish it from a multilayer perceptron, which is a misnomer for a more complicated neural network. As a linear classifier, the single-layer perceptron is the simplest feedforward neural network.

Learning algorithm

Below is an example of a learning algorithm for a single-layer perceptron. For multilayer perceptrons, where a hidden layer exists, more sophisticated algorithms such as backpropagation must be used. If the activation function or the underlying process being modeled by the perceptron is nonlinear, alternative learning algorithms such as the delta rule can be used as long as the activation function is differentiable. Nonetheless, the learning algorithm described in the steps below will often work, even for multilayer perceptrons with nonlinear activation functions.

When multiple perceptrons are combined in an artificial neural network, each output neuron operates independently of all the others; thus, learning each output can be considered in isolation.

Definitions

We first define some variables:

- r is the learning rate of the perceptron. Learning rate is between 0 and 1. Larger values make the weight changes more volatile.

- denotes the output from the perceptron for an input vector .

- is the training set of samples, where:

- is the -dimensional input vector.

- is the desired output value of the perceptron for that input.

We show the values of the features as follows:

- is the value of the th feature of the th training input vector.

- .

To represent the weights:

- is the th value in the weight vector, to be multiplied by the value of the th input feature.

- Because , the is effectively a bias that we use instead of the bias constant .

To show the time-dependence of , we use:

- is the weight at time .

Steps

- Initialize the weights. Weights may be initialized to 0 or to a small random value. In the example below, we use 0.

- For each example j in our training set D, perform the following steps over the input and desired output :

- Calculate the actual output:

- Update the weights:

- , for all features , is the learning rate.

- Calculate the actual output:

- For offline learning, the second step may be repeated until the iteration error is less than a user-specified error threshold , or a predetermined number of iterations have been completed, where s is again the size of the sample set.

The algorithm updates the weights after every training sample in step 2b.

Convergence

The perceptron is a linear classifier, therefore it will never get to the state with all the input vectors classified correctly if the training set D is not linearly separable, i.e. if the positive examples cannot be separated from the negative examples by a hyperplane. In this case, no "approximate" solution will be gradually approached under the standard learning algorithm, but instead, learning will fail completely. Hence, if linear separability of the training set is not known a priori, one of the training variants below should be used.

If the training set is linearly separable, then the perceptron is guaranteed to converge.[14] Furthermore, there is an upper bound on the number of times the perceptron will adjust its weights during the training.

Suppose that the input vectors from the two classes can be separated by a hyperplane with a margin , i.e. there exists a weight vector , and a bias term b such that for all with and for all with , where is the desired output value of the perceptron for input . Also, let R denote the maximum norm of an input vector. Novikoff (1962) proved that in this case the perceptron algorithm converges after making updates. The idea of the proof is that the weight vector is always adjusted by a bounded amount in a direction with which it has a negative dot product, and thus can be bounded above by O(√t), where t is the number of changes to the weight vector. However, it can also be bounded below by O(t) because if there exists an (unknown) satisfactory weight vector, then every change makes progress in this (unknown) direction by a positive amount that depends only on the input vector.

While the perceptron algorithm is guaranteed to converge on some solution in the case of a linearly separable training set, it may still pick any solution and problems may admit many solutions of varying quality.[15] The perceptron of optimal stability, nowadays better known as the linear support-vector machine, was designed to solve this problem (Krauth and Mezard, 1987).[16]

Information Theory

From an information theory point of view, a single perceptron with K inputs has a capacity of 2K bits of information.[17]

Variants

The pocket algorithm with ratchet (Gallant, 1990) solves the stability problem of perceptron learning by keeping the best solution seen so far "in its pocket". The pocket algorithm then returns the solution in the pocket, rather than the last solution. It can be used also for non-separable data sets, where the aim is to find a perceptron with a small number of misclassifications. However, these solutions appear purely stochastically and hence the pocket algorithm neither approaches them gradually in the course of learning, nor are they guaranteed to show up within a given number of learning steps.

The Maxover algorithm (Wendemuth, 1995) is "robust" in the sense that it will converge regardless of (prior) knowledge of linear separability of the data set.[18] In the linearly separable case, it will solve the training problem – if desired, even with optimal stability (maximum margin between the classes). For non-separable data sets, it will return a solution with a small number of misclassifications. In all cases, the algorithm gradually approaches the solution in the course of learning, without memorizing previous states and without stochastic jumps. Convergence is to global optimality for separable data sets and to local optimality for non-separable data sets.

The Voted Perceptron (Freund and Schapire, 1999), is a variant using multiple weighted perceptrons. The algorithm starts a new perceptron every time an example is wrongly classified, initializing the weights vector with the final weights of the last perceptron. Each perceptron will also be given another weight corresponding to how many examples do they correctly classify before wrongly classifying one, and at the end the output will be a weighted vote on all perceptrons.

In separable problems, perceptron training can also aim at finding the largest separating margin between the classes. The so-called perceptron of optimal stability can be determined by means of iterative training and optimization schemes, such as the Min-Over algorithm (Krauth and Mezard, 1987)[16] or the AdaTron (Anlauf and Biehl, 1989)).[19] AdaTron uses the fact that the corresponding quadratic optimization problem is convex. The perceptron of optimal stability, together with the kernel trick, are the conceptual foundations of the support-vector machine.

The -perceptron further used a pre-processing layer of fixed random weights, with thresholded output units. This enabled the perceptron to classify analogue patterns, by projecting them into a binary space. In fact, for a projection space of sufficiently high dimension, patterns can become linearly separable.

Another way to solve nonlinear problems without using multiple layers is to use higher order networks (sigma-pi unit). In this type of network, each element in the input vector is extended with each pairwise combination of multiplied inputs (second order). This can be extended to an n-order network.

It should be kept in mind, however, that the best classifier is not necessarily that which classifies all the training data perfectly. Indeed, if we had the prior constraint that the data come from equi-variant Gaussian distributions, the linear separation in the input space is optimal, and the nonlinear solution is overfitted.

Other linear classification algorithms include Winnow, support-vector machine, and logistic regression.

Multiclass perceptron

Like most other techniques for training linear classifiers, the perceptron generalizes naturally to multiclass classification. Here, the input and the output are drawn from arbitrary sets. A feature representation function maps each possible input/output pair to a finite-dimensional real-valued feature vector. As before, the feature vector is multiplied by a weight vector , but now the resulting score is used to choose among many possible outputs:

Learning again iterates over the examples, predicting an output for each, leaving the weights unchanged when the predicted output matches the target, and changing them when it does not. The update becomes:

This multiclass feedback formulation reduces to the original perceptron when is a real-valued vector, is chosen from , and .

For certain problems, input/output representations and features can be chosen so that can be found efficiently even though is chosen from a very large or even infinite set.

Since 2002, perceptron training has become popular in the field of natural language processing for such tasks as part-of-speech tagging and syntactic parsing (Collins, 2002). It has also been applied to large-scale machine learning problems in a distributed computing setting.[20]

References

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R. E. (1999). "Large margin classification using the perceptron algorithm" (PDF). Machine Learning. 37 (3): 277–296. doi:10.1023/A:1007662407062. S2CID 5885617.

- Bishop, Christopher M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer. ISBN 0-387-31073-8.

- McCulloch, W; Pitts, W (1943). "A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity". Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259.

- Rosenblatt, Frank (1957). "The Perceptron—a perceiving and recognizing automaton". Report 85-460-1. Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory.

- Olazaran, Mikel (1996). "A Sociological Study of the Official History of the Perceptrons Controversy". Social Studies of Science. 26 (3): 611–659. doi:10.1177/030631296026003005. JSTOR 285702. S2CID 16786738.

- Hay, John Cameron (1960). Mark I perceptron operators' manual (Project PARA) /. Buffalo: Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory.

- Sejnowski, Terrence J. (2018). The Deep Learning Revolution. MIT Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-262-03803-4.

- O’Connor, Jack (2022-06-21). "Undercover Algorithm: A Secret Chapter in the Early History of Artificial Intelligence and Satellite Imagery". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence: 1–15. doi:10.1080/08850607.2022.2073542. ISSN 0885-0607. S2CID 249946000.

- Aizerman, M. A.; Braverman, E. M.; Rozonoer, L. I. (1964). "Theoretical foundations of the potential function method in pattern recognition learning". Automation and Remote Control. 25: 821–837.

- Mohri, Mehryar; Rostamizadeh, Afshin (2013). "Perceptron Mistake Bounds". arXiv:1305.0208 [cs.LG].

- Cash, Sydney; Yuste, Rafael (1999). "Linear Summation of Excitatory Inputs by CA1 Pyramidal Neurons". Neuron. 22 (2): 383–394. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81098-3. PMID 10069343.

- Liou, D.-R.; Liou, J.-W.; Liou, C.-Y. (2013). Learning Behaviors of Perceptron. iConcept Press. ISBN 978-1-477554-73-9.

- Rosenblatt, F. (1958). "The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain". Psychological Review. 65 (6): 386–408. doi:10.1037/h0042519. ISSN 1939-1471.

- Novikoff, Albert J. (1963). "On convergence proofs for perceptrons". Office of Naval Research.

- Bishop, Christopher M (2006-08-17). "Chapter 4. Linear Models for Classification". Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p. 194. ISBN 978-0387-31073-2.

- Krauth, W.; Mezard, M. (1987). "Learning algorithms with optimal stability in neural networks". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 20 (11): L745–L752. Bibcode:1987JPhA...20L.745K. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/20/11/013.

- MacKay, David (2003-09-25). Information Theory, Inference and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge University Press. p. 483. ISBN 9780521642989.

- Wendemuth, A. (1995). "Learning the Unlearnable". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 28 (18): 5423–5436. Bibcode:1995JPhA...28.5423W. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/28/18/030.

- Anlauf, J. K.; Biehl, M. (1989). "The AdaTron: an Adaptive Perceptron algorithm". Europhysics Letters. 10 (7): 687–692. Bibcode:1989EL.....10..687A. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/10/7/014. S2CID 250773895.

- McDonald, R.; Hall, K.; Mann, G. (2010). "Distributed Training Strategies for the Structured Perceptron" (PDF). Human Language Technologies: The 2010 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the ACL. Association for Computational Linguistics. pp. 456–464.

Further reading

- Aizerman, M. A. and Braverman, E. M. and Lev I. Rozonoer. Theoretical foundations of the potential function method in pattern recognition learning. Automation and Remote Control, 25:821–837, 1964.

- Rosenblatt, Frank (1958), The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain, Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, Psychological Review, v65, No. 6, pp. 386–408. doi:10.1037/h0042519.

- Rosenblatt, Frank (1962), Principles of Neurodynamics. Washington, DC: Spartan Books.

- Minsky, M. L. and Papert, S. A. 1969. Perceptrons. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gallant, S. I. (1990). Perceptron-based learning algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 179–191.

- Mohri, Mehryar and Rostamizadeh, Afshin (2013). Perceptron Mistake Bounds arXiv:1305.0208, 2013.

- Novikoff, A. B. (1962). On convergence proofs on perceptrons. Symposium on the Mathematical Theory of Automata, 12, 615–622. Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

- Widrow, B., Lehr, M.A., "30 years of Adaptive Neural Networks: Perceptron, Madaline, and Backpropagation," Proc. IEEE, vol 78, no 9, pp. 1415–1442, (1990).

- Collins, M. 2002. Discriminative training methods for hidden Markov models: Theory and experiments with the perceptron algorithm in Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP '02).

- Yin, Hongfeng (1996), Perceptron-Based Algorithms and Analysis, Spectrum Library, Concordia University, Canada

External links

- A Perceptron implemented in MATLAB to learn binary NAND function

- Chapter 3 Weighted networks - the perceptron and chapter 4 Perceptron learning of Neural Networks - A Systematic Introduction by Raúl Rojas (ISBN 978-3-540-60505-8)

- History of perceptrons

- Mathematics of multilayer perceptrons

- Applying a perceptron model using scikit-learn - https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.linear_model.Perceptron.html