Lahijan

Lahijan, (Persian: لاهیجان, romanized: Lāhijān) also referred to as Lāyjon in the Gilaki language,[3] is a prominent city situated in close proximity to the Caspian Sea within the Central District of Lahijan County, located in the Gilan province of Iran. It serves a dual role as the capital of both the district and the county.

Lahijan

Persian: لاهیجان | |

|---|---|

City | |

).jpg.webp)  National Tea Museum, Lahijan artificial lake's view from the top of Sheitan Koh (Satan's hill), Zahed Gilani Tomb, Lahiajan Brick Bridge | |

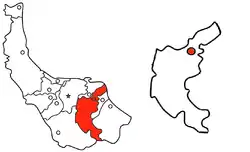

Location in Gilan Province and the Lahijan County | |

Lahijan Location in Iran | |

| Coordinates: 37°12′15″N 50°00′17″E[1] | |

| Country | |

| Province | Gilan |

| County | Lahijan |

| District | Central |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,428 km2 (551 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 101,073 |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| Area code | +98-13 |

According to the 2006 National Census, the population of Lahijan was recorded at 71,871 individuals residing in 21,518 households.[4] Subsequent censuses, conducted in 2011 and 2016, reported a notable increase in the population, with 94,051 people in 30,311 households in 2011[5] and 101,073 people in 34,497 households in 2016.[2]

Lahijan is distinguished by its blend of traditional and modern architectural styles. Situated on the northern slope of the Alborz Mountains, the city exhibits an Iranian-European urban structure. Its culture and favorable climatic conditions have positioned Lahijan as a significant tourist destination in northern Iran. The city's foundations are built upon sediments deposited by prominent rivers in Gilan, including the Sepid/Sefid-Rud (White River). Throughout history, Lahijan has been a prominent commercial center and served as the capital of East Gilan under specific rulers. Over various historical periods, Lahijan has garnered recognition as a notable tourism hub within the Islamic world.

Etymology

Lahijan is a toponym derived from the economic activities historically prevalent within the city. The term Lāhijān finds its roots in two distinct Persian words: "Lah," denoting silk, and "Jan" or "Gan," representing a location where activities are carried out. Therefore, when combining these components, the resulting term "Lahijan" or "lahigan" translates to "a place for obtaining silk fiber."

Professor Bahram Farah'vashi, an esteemed Iranian expert in ancient languages, has elucidated that, in the Middle Persian Language, "Lah" signifies silk, and in the context of the Decisive Argument, "Lah" specifically refers to red silk. Consequently, "Lahygan" (modern-day Lahijan) designates a geographic area associated with the acquisition of silk.

History

In ancient times, the Gilan region was indeed divided into 'the Caspian' and 'the Golha' (flowers) sub-regions. Before Iran's present provincial divisions, the Sefid-Rud River did indeed partition Gilan into eastern and western regions, with the river's eastern side referred to as Biehpish and the western side as Biehpas. Lahijan did become the capital of Biehpish at a certain point in time. The region has historically been a major silk-producing center in Iran and was indeed the country's first area for tea cultivation, set out by Prince Mohammad Mirza, known as "Kashef-ol-Saltaneh."

Prince Mohammad Mirza's role in tea cultivation and his strategy to learn the secrets of tea production while posing as a French laborer in British-controlled India is a factual account. He successfully transported tea samples back to Iran, which was instrumental in initiating tea cultivation in the country. His mausoleum in Lahijan is now part of the "Iran Tea Museum."

Lahijan's historical foundation is attributed to 'Lahij Ebne Saam.' Furthermore, the Mongol ruler Oljaito conquered Lahijan in 705 AH, and Amir Teimoor attacked the region. Indeed, Shah Abbas defeated 'Khan Ahmad,' leading to subsequent Safavid governance over the city. Historical events, such as the outbreak of plague in 703, a conflagration in 850, and the occupation of Lahijan by the Russian army in June 1725,[6] are well-documented. Additionally, Lahijan played a significant role as one of the main bases of the Jungle Movement.

Geography

Lahijan population enjoys a climate known as "moderate Caspian". This weather pattern emerged from the influence of the currents of both the Alborz Mountains slopes and the Caspian Sea. But before learning about this weather pattern, the model of the climate system and Gilan's spatial geo system should be discussed.

Gilan includes the north-western end of the Alborz chain and the western part of the Caspian lowlands of Persia. The mountainous belt is cut through by the deep transverse valley of the Sefid-Rud between Manjil and Eemamzadeh Hashem near Rasht, the capital of Gilan Province. To the northwest, the Talesh highlands stretch a continuous watershed separating Gilan and Azerbaijan.

Except at their northern end, where the Heyran passes at the top of the Āstārāčāy valley does not exceed 1600 m, they are over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) high, with three spots over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) including the Baqrow Daḡ, the Ajam Daḡ, and the Shah Moʿallem or Masouleh Daḡ. Their eastern and north-eastern side is deeply carved by parallel streams flowing down towards the Caspian, resulting in a comb-shaped pattern. The western Alborz itself, to the east of the Safid-rud valley, is wider and more intricate, with three parallel (WNW-ESE) ranges; the southernmost and lowest one is represented in Gilan by the Asman-sara Kuh in the Ammarlu district; the medium one is the most continuous, from the Kuh-e-Dalfak to the Keram Kuh, whereas the transverse valley of Polrud clearly divides the northern range into Kuh-e-Natesh and Kuh-e-Somam or Somamus, the highest spot of Gilan. All these mountains have a very complicated geological structure and tectonic history which connects them to the structural complex of central Persia.

Though all those mountains cover a greater area than the plains, these are the most specific features of the province, and locally, the word Gilan often refers to the plain areas or particularly to the central plain.

This large parallelogram of lowlands is heterogeneous and can be divided into two main parts: The delta of the Safid-rud in the east and the Fumanat plain in the west. The former has been entirely built by the Safid-rud, a river with a high discharge and a high alluvial content. The higher part is made out of coarse ancient alluvial material, whereas in the lower part, north of Astaneh-e Ashrafiyyeh, the river often changed its course through thin silty and clayey material; it has thus abandoned its former northeastward course, which flowed into the sea at the prominent angle of the plain near Dastak, and presently flows northwards and builds a smaller living delta jutting out into the Caspian between Zibakenar and Bandar kiashahr.

The Fumanat plain to the west intermingles marine alluvial deposits and former sandy beach lines with abundant alluvial deposits from the numerous rivers draining the southern part of Talesh highlands. They do not reach directly the sea but converge into the lagoon of Anzali with a single outlet to the Caspian through the dune-covered sandy coastline. The lagoon is constantly getting smaller and shallower under the effect of silting. On the contrary, the streams of northern Talesh and eastern Gilan, even the more abundant Polrud, do not bring alluvium enough to counterbalance the action of a coastal current going eastward, and thus could not build more than a narrow ribbon of lowlands, only a few kilometers wide between Astara and Safid-rud and to the east of Qasemabad, and some 10 km wide at the mouth of the Polrud around kelachay.

Climate and weather

The topographic position of the Caspian lowlands results in a very characteristic Hyrcanian climate, and the whole province of Gilan belongs to this humid and green area. Prevailing north-south atmospheric currents, humidified over the Caspian, are forced to a vigorous ascendancy by the mighty barrier of Alborz and thus pour abundant rainfall all year long on both the plain and the north-western slope of the mountains. The precipitation regime shows a sharp maximum in autumn (September to December), when atmospheric instability is at its highest point, medium values in winter and early spring, and lowest values from May to August.

Mean annual rainfall varies between 1200 and 1800 mm along the shoreline, decreases towards a sub-humid area in the southwestern corner of the, and reaches again very high amounts in the lower part of the mountain, up to 1500–1800 mm. Along the Safid-rud valley, swept every afternoon in summer by the violent northerly Manjil wind (Tholozan), a very rapid transition leads to the Mediterranean-like semi-arid area of Rudbar and Manjil.

The climatic privilege of Gilan explains its luxuriant natural vegetation.

According to altitude, three forest levels can be distinguished: The Hyrcanian mixed forests, the mountain beech forest, and the High Mountain oak and hornbeam forest. The Hyrcanian forest stricto sensu once covered the plains, where only residual patches remain on coarse alluvial terraces between cultivated areas, and still covers the greater part of the first slopes of the mountains up to about 1000 m.

It is a stratified forest, with a layer of very tall trees such as the endemic chestnut-leaved oak (boland-mazu; Quercus castaneaefolia), Siberian elm (derakht-e-azad; Zelkova crenata) and iron tree (anjili; Parrotia persica) and more common elms, maples, and hornbeams (ulas); a layer of smaller trees like the endemic Gleditchia caspica (lilaki), Diospyros lotus (kalhu), and Albizzia julibrissin (shabkhosb), boxwood (shemshad) in shady spots and all kinds of wild fruit trees; and an underwood with evergreen bushes such as Prunus laurocerasus (jal) and holly (khas), moss, wild vine, ivy, and other creeping plants. Medium altitude mountains are the realm of the lofty oriental beech (rash; Fagus orientalis), associated with oaks (balut), lime-trees (namdar), maples (afra), and elms (narvan; qq.v.). The upper mountain level, between 1800 and 2200 m, has remnants of a quite poorer forest of stunted oaks (uri; Quercus macranthera) and hornbeams (Carpinus orientalis). Alpine meadows, climate at higher altitudes, have often replaced these upper mountain forests, some of them, on the highest ridges or sheltered slopes, show distinctly xerophytic features.

The so-called Mediterranean island around Rudbar and Manjil is conspicuous through its specific vegetation, natural as well as cultivated, i.e., its very sparse cypress forests and its olive groves.

The weather system in Lahijan is more favorable than the other points in the Gilan. It has warmer winters and cooler summers. Freezing temperatures are seldom reported in the coastal areas; however, it is not odd for Lahijan to experience periods of near blizzard conditions during the winter. The amount of rainfall in Lahijan depends on the winds bearing vapor that blows from the North West in winter, from the East in spring, and from the West in summer and autumn. These winds carry the vapor and humidity towards the plains causing heavy and prolonged rainfalls.

Districts

Keshavarzi - Khamir Kalaye - Gharib Abad - Amir Shahid - Pordesar - Shishe Garan - Ordubazar - Khazar St. - Karegar (Shahid Rajayi)- Andisheh - Shahrake Salman - Shahrake Janbazan - Yousef Abad - Chahar Padeshahan - Sardare Jangal - Shoron Maleh - Khoramshahr - Ghiam St. - Bolvar St. - Nima St. - Jire Sar - Koucheh Bargh - Malek-e-Ashtar - Bazkia Gorab - Shaghayegh St. - East & West Kashef St. - Hazin St. - Sheikh Zahed Village - 22 Aban - Shahid Karimi St. - Bazar Rooz 1 2 3 4 - Shahrake Tarbiat Mo'allem - Shahrake Farhangian - Kamarbandi - Pomp Benzin - Golestan Alleies - Azadegan St. - Taleghani St. - Sher Bafan - Ghasab Mohaleh - Lashidan-e-Hokomati - Lashidan - Tarbiat Mo'allem St. - Assyed Yamani Alley - Abshar & Damaneh - Gabaneh - Karvan Sara Bar - Fayath St. - Hassan Bigdesht - Haji Abad - Asour Meli - Javaher Poshteh - Kord-e-Mahaleh - Namak Abi - Koi Zamani - . . .

Neighborhoods

Sustan, also known as Soustan, is a diminutive village nestled in the southern region of Lahijan, characterized by its division into two distinct districts: Upper and Lower. The village boasts a notable natural pool situated in its southeastern expanse, commonly referred to by locals as Soustan'sal. The pool garners considerable attention as a prominent tourist attraction within the area. At its heart lies a natural island adorned with ancient trees, enhancing its scenic allure.

Functionally, Soustan'sal plays a vital role in the local agricultural landscape, serving as a critical irrigation source for the surrounding tea fields and paddy lands. This natural reservoir also supports the community's economic activities, aiding in the sustenance and growth of the region's agricultural sector.

Adjacent to the pool, one can find the Shin'chal sand mine—an open mine prevalent in the vicinity. This mining site is of substantial economic significance, as contractors extract tens of thousands of tonnes of sand annually from this locality. The extracted sand contributes to various construction and industrial endeavors, further underlining the economic importance of this natural resource.

Kat'schel, on the other hand, is a diminutive village situated in the eastern reaches of Lahijan. Notably, it holds the distinction of being the closest neighboring village to Sustan, highlighting its geographical proximity to the aforementioned village.

Tea

Tea in Iran

The history of tea in Iran traces its origins to the latter part of the 15th century. Prior to this, coffee held prominence as the primary beverage in the region. However, logistical challenges associated with shipping coffee from distant producer nations led to a shift in preference towards tea. Positioned along the historical trade route known as "The Silk Road", Iran found China, a major tea-producing nation, more accessible for trade. This ease of transportation facilitated the increased popularity of tea in Iran over time. As tea consumption surged, so did the demand, necessitating larger imports to match the consumption patterns.

In the year 1882, Iran made its initial attempt to cultivate tea within its borders, importing seeds from India. However, the venture proved unsuccessful. Subsequently, in 1899, Prince Mohammad Mirza, also recognized as "Kashef Al Saltaneh" and born in Lahijan, imported Indian tea and initiated its cultivation in Lahijan. Displaying ingenuity, Kashef, the inaugural mayor of Tehran and an Iranian ambassador to British-ruled India, concealed his true identity by posing as a French laborer to glean insights into tea production. His objective was to obtain tea saplings for cultivation in Iran. Successfully executing his plan, he transported 3,000 saplings from the Kangra region in Northern India, utilizing his diplomatic immunity to avert scrutiny. Commencing cultivation in the Gilan region, south of the Caspian Sea, the climate of Gilan proved conducive to tea cultivation, leading to a swift expansion of the tea industry in Gilan and Mazanderan. Presently, Kashef's mausoleum in Lahijan stands as an integral part of "Iran's National Tea Museum."

A pivotal milestone in the tea industry materialized in 1934 with the establishment of the first modern-style tea factory. The industry has since burgeoned, with approximately 107 tea factories and a collective expanse of 32,000 hectares devoted to tea farms. These farms, predominantly situated on the slopes of Iran, akin to those in Darjeeling, specialize in producing orthodox-style black tea. The Iranian tea boasts a reddish hue and a delicate flavor profile.

By the year 2009, the aggregate production of black tea in Iran amounted to approximately 60,000 tons.[7]

Tea in Lahijan

Historically, Lahijan is the first town in Iran to have tea plantations. With its mild weather, soil quality and fresh spring water, Lahijan stands to have the largest area of tea cultivation in Iran.

But today the country's tea industry is deep in trouble as the verdant gardens that once sustained millions of farmers and their workers are used only for grazing and other personal purposes. Despite having one of the world's most avid tea-drinking populations, the Iranian tea economy is reeling from an influx of foreign imports and smugglers who, as per the complaints of local traders, often have close family ties to powerful figures in the Islamic government. As a consequence, Lahijan, this historic capital of Iran's tea industry which was once a lush vista of tea bushes is now occupied by real estate. These buildings and structures are built by tea factory owners who have moved into real estate in response to their industry's decline. Several of the town's tea mills are derelict. Others are at a standstill or operating at half capacity. Some 40% of the half-million tea farmers in tea-rich Gilan province have gone out of business because the factories are no longer buying their crops. Hundreds of thousands of pickers have been forced out of work.

Tourist hubs

).jpg.webp)

Sheitan Koh (Satan's Hill) and its waterfall - Sareshke - Baam-e-Sabz - Lahijan Pool (Estakhr) - the Tomb of the Four king (Char Padeshahan) - Golshan Bath - Sheikh Zahed Gilani Tomb - Shen Chal & Sustan Pool - Lahijan Daily Markets No.1 and No.2 - Iran National Tea Museum - Brick Bridge (pole Kheshti) - Amjadossoltan (Tomb of Farah Pahlavi(Diba)'s ancestor - National Library) - Lahidjan gondola - At'ah Kuh - Bulvar . . .

Lahijan Pool

Lahijan Pool, also known as the Lahijan Reservoir, is an essential water resource situated in the eastern part of Lahijan, a city in Gilan Province, Iran. Nestled atop the scenic Sheitankuh Mountain, this reservoir is enveloped in vibrant greenery and bush, offering a picturesque backdrop. Historically referred to as Shahneshin, the reservoir is pivotal for irrigation purposes, particularly catering to the adjacent rice fields.

Covering an extensive area of 17 hectares and boasting a maximum depth of 4 meters, the reservoir is replenished by water flowing from the mountains. One notable feature is the presence of a prominent structure known as "the beauty in the middle of the lake,” historically referred to as "between the backs." This structure is connected to the southern edge of the reservoir through a lengthy concrete bridge. The reservoir stretches for about 2 kilometers, bordered by a charming boulevard that enhances its appeal as a popular sightseeing and recreational destination.

According to local accounts, it is believed that Shah Abbas Safavid, a significant ruler of the Safavid dynasty, commissioned the construction of this reservoir. There were plans to build an expansive palace on the reservoir's island, intended to serve as a residence for Shah Abbas Safavid during his visits to Lahijan. However, as of the present day, there are no visible remnants or traces of this envisioned palace. The historical and geographical significance of the Lahijan Pool makes it an important landmark within the region, attracting visitors for its natural beauty and cultural associations.[8]

Special ceremony

_4.jpg.webp)

The musical instrument known as "Karb," also referred to as "Kareb" or "cymbal," is a traditional percussive instrument in Iranian culture. It is made from two sturdy pieces of wood, typically played by striking them together. The player holds the pieces of wood through a leather belt, allowing for controlled and rhythmic percussion sounds. This design serves as a safer alternative to the previous use of stones for percussion. Karb is an integral part of traditional music and is often played in ensembles to create a specific rhythmic pattern. It is particularly popular in various regions of Iran, including Aran, Kashan, select districts in Semnan, as well as Sabzevar and Lahijan.

The traditional ritual of stone beating, known as "karb" in Persian, is a symbolic practice prevalent in several parts of Iran, often associated with mourning and commemorative ceremonies. The ritual involves the rhythmic striking of two pieces of stone against the sides of a mourner's body, following specific methods and movements, accompanied by mournful songs. However, due to the potential physical harm caused by the stones, wooden sticks are gradually supplanting them in this ritual. Contemporary terms such as "Karbzani" or "Karebzani," along with playing cymbals and ratchets, are now used in place of stone beating. Notably, regions like Mazandaran and Komesh, situated south of the Alborz Mountains, use the term "Kareb," while Gilan employs "Karb," and in Aran (Kashan), the term "cymbal" is customary.

The performance of this ceremony demands considerable physical strength from the participants and remains a significant cultural and religious practice in certain areas, such as Lahijan and Aran (Kashan), as well as Semnan and Sabzevar.

In addition to Karb, another significant aspect of musical traditions during rituals is "Karna Nawazi," involving the use of "Karna," which translates to trumpet or horn. In certain villages in Gilan, including Mashk, Lasht, and Rudbeneh in Lahijan, long Karnas, constructed from reeds with a staff-like bend made of squash at one end and a wooden mouthpiece at the other, are employed during Ashura ceremonies. These unique trumpets, known as "martyrdom songs," find use in passion plays and other Ashurayi ceremonies, with alternating performances by a singer and a group of Karna players during specific rituals. This practice reflects the rich cultural and musical diversity present in various regions of Iran.

Cuisine

The following are some popular dishes in Lahijanian cuisine:

Lahijanian cuisine is characterized by a diverse array of dishes, each holding a significant place in the culinary traditions of the region. Among the popular dishes are Mirza Ghassemi, Torshe'tare, Bademjan'khoroush, Sir'vabichke Morgh-e-Lako, Baghali ghatogh, Torshe Tare, Koii Khorosh, Sir ghalieh, Alo Mosama, Naz Khatoon, Chaghar Tameh, Anarbij, Shesh Andaz, Shirin Tare, Sirabij, Khali Ovei, Chakhardameh, Motonjen, Loongi, Ghorabij, Mahi Febij, Vavishkah, Torshe Shami, Shami, Halichoe, Kaleh kabab, and Tabironey.

Cookies (kulucheh)

One particularly renowned element of Lahijanian cuisine is the traditional Persian-style filled cookie known as "Kulucheh." These cookies, widely recognized and sought after, are marketed globally. Kulucheh features a crusty shell enveloping a soft and flavorful filling. The filling comes in a variety of options, including cocoa, walnut, and coconut flavors. The age-old production of these cookies in Gilan has adhered to traditional methods over centuries. Four well-known brands associated with the production of Kulucheh cookies in Lahijan include Noosheen, Grand Naderi, Naderi, Nadi, and Peyman, all contributing to the reputation of Lahijan's culinary heritage.

Cinema and theater centers

There were two movie centers in Lahijan, Be'sat and Shahr-e-Sabz. They were once important destinations for the people of Lahijan. However, around 10 years ago, because of economic meltdown in the city, both movie centers went bankrupt, resulting in their shut down. Despite this, Shahr-e-Sabz was rebuilt and re-opened in 2012.

Universities and schools

There are two kinds of university in Lahijan, state and non-state (semi-private) universities.

State universities

- Hazrat Zeinab School of Nursing and Midwifery, East Gilan

- Lahijan Payam-Noor University

- Tarbiat Modarres College, Lahijan

Non-state universities

Notable people from Lahijan

- Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi Gilani - Founder of Sharif University of Technology and Principal of Alborz High School.

- Hazin Lahiji - Iranian Poet and Scholar

- Sheikh Zahed Gilani - Grandmaster of the famed Zahediyeh Sufi Order at Lahijan

- Farideh Ghotbi (1920–2000), mother of Farah Diba Pahlavi, former Shahbanu.[9]

- Hassan Zia-Zarifi - Iranian intellectual and one of the founders of the communist guerrilla movement in Iran

- Bijan Najdi - Poet and Writer

- Reza Qotbi - Head of Iranian National TV

- Abolhassan Ziyā-Zarifi, public health specialist

Gallery

Lahijan in winter

Lahijan in winter The sidewalk around the Lahijan lake

The sidewalk around the Lahijan lake.jpg.webp) A sidewalk in lahijan after morning snow

A sidewalk in lahijan after morning snow Tea plantations at the outskirt hills of Lahijan

Tea plantations at the outskirt hills of Lahijan

![]() Media related to Lahijan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lahijan at Wikimedia Commons

References

- OpenStreetMap contributors (4 October 2023). "Lahijan, Lahijan County" (Map). OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Archived from the original (Excel) on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Lahijan can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3072747" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011)" (Excel). Iran Data Portal (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Hanway, Jonas (1754). An historical account of the British Trade over the Caspian Sea: with the Author's Journal of Travels from England through Russia into Persia, and back through Russia, Germany and Holland : To which are added the Revolution of Persia during the present Century, with the particular History of the great Usurper Nadir Kouli ; Illustrated with Maps and Copper-Plates ; In two volumes. ¬The Revolutions of Persia : Containing the Reign of Shah Sultan Hussein; the invasion of the Afghans and the Reigns of Sultan Mir Maghmud ... Osborne.

- History of tea in Iran

- Pariya Mashkabadi and Mehdi Hamzenejhad, Water management methods in both cold and humid ecosystems in Iran Case study: Shahgoli, Tabriz, Lahijan pool, 2009, Haft shahr 154 .no 55,56

- Afkhami, Gholam Reza (12 January 2009). The Life and Times of the Shah. University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-520-94216-5.