Machine learning in bioinformatics

Machine learning in bioinformatics is the application of machine learning algorithms to bioinformatics,[1] including genomics, proteomics, microarrays, systems biology, evolution, and text mining.[2][3]

Prior to the emergence of machine learning, bioinformatics algorithms had to be programmed by hand; for problems such as protein structure prediction, this proved difficult.[4] Machine learning techniques, such as deep learning can learn features of data sets, instead of requiring the programmer to define them individually. The algorithm can further learn how to combine low-level features into more abstract features, and so on. This multi-layered approach allows such systems to make sophisticated predictions when appropriately trained. These methods contrast with other computational biology approaches which, while exploiting existing datasets, do not allow the data to be interpreted and analyzed in unanticipated ways. In recent years, the size and number of available biological datasets have skyrocketed.[2]

Tasks

Machine learning algorithms in bioinformatics can be used for prediction, classification, and feature selection. Methods to achieve this task are varied and span many disciplines; most well known among them are machine learning and statistics. Classification and prediction tasks aim at building models that describe and distinguish classes or concepts for future prediction. The differences between them are the following:

- Classification/recognition outputs a categorical class, while prediction outputs a numerical valued feature.

- The type of algorithm, or process used to build the predictive models from data using analogies, rules, neural networks, probabilities, and/or statistics.

Due to the exponential growth of information technologies and applicable models, including artificial intelligence and data mining, in addition to the access ever-more comprehensive data sets, new and better information analysis techniques have been created, based on their ability to learn. Such models allow reach beyond description and provide insights in the form of testable models.

Machine learning approaches

Artificial neural networks

Artificial neural networks in bioinformatics have been used for:[5]

- Comparing and aligning RNA, protein, and DNA sequences.

- Identification of promoters and finding genes from sequences related to DNA.

- Interpreting the expression-gene and micro-array data.

- Identifying the network (regulatory) of genes.

- Learning evolutionary relationships by constructing phylogenetic trees.

- Classifying and predicting protein structure.

- Molecular design and docking.

Feature engineering

The way that features, often vectors in a many-dimensional space, are extracted from the domain data is an important component of learning systems.[6] In genomics, a typical representation of a sequence is a vector of k-mers frequencies, which is a vector of dimension whose entries count the appearance of each subsequence of length in a given sequence. Since for a value as small as the dimensionality of these vectors is huge (e.g. in this case the dimension is ), techniques such as principal component analysis are used to project the data to a lower dimensional space, thus selecting a smaller set of features from the sequences.[6]

Classification

In this type of machine learning task, the output is a discrete variable. One example of this type of task in bioinformatics is labeling new genomic data (such as genomes of unculturable bacteria) based on a model of already labeled data.[6]

Hidden Markov models

Hidden Markov models (HMMs) are a class of statistical models for sequential data (often related to systems evolving over time). An HMM is composed of two mathematical objects: an observed state‐dependent process , and an unobserved (hidden) state process . In an HMM, the state process is not directly observed – it is a 'hidden' (or 'latent') variable – but observations are made of a state‐dependent process (or observation process) that is driven by the underlying state process (and which can thus be regarded as a noisy measurement of the system states of interest).[7] HMMs can be formulated in continuous time.[8][9]

HMMs can be used to profile and convert a multiple sequence alignment into a position-specific scoring system suitable for searching databases for homologous sequences remotely.[10] Additionally, ecological phenomena can be described by HMMs.[11]

Convolutional neural networks

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) are a class of deep neural network whose architecture is based on shared weights of convolution kernels or filters that slide along input features, providing translation-equivariant responses known as feature maps.[12][13] CNNs take advantage of the hierarchical pattern in data and assemble patterns of increasing complexity using smaller and simpler patterns discovered via their filters. Therefore, they are lower on a scale of connectivity and complexity.

Convolutional networks were inspired by biological processes[14][15][16][17] in that the connectivity pattern between neurons resembles the organization of the animal visual cortex. Individual cortical neurons respond to stimuli only in a restricted region of the visual field known as the receptive field. The receptive fields of different neurons partially overlap such that they cover the entire visual field.

CNN uses relatively little pre-processing compared to other image classification algorithms. This means that the network learns to optimize the filters (or kernels) through automated learning, whereas in traditional algorithms these filters are hand-engineered. This independence from prior knowledge and human intervention in feature extraction is a major advantage.

Phylogenetic convolutional neural networks

A phylogenetic convolutional neural network (Ph-CNN) is a novel convolutional neural network architecture proposed by Fioranti et al. to classify metagenomics data.[18] In this approach, phylogenetic data is endowed with patristic distance (the sum of the lengths of all branches connecting two operational taxonomic units [OTU]) to select k-neighborhoods for each OTU, and each OTU and its neighbors are processed with convolutional filters. Ph-CNN achieves promising results compared to fully connected neural networks, random forest and support vector machines.[18]

Self-supervised learning

Unlike supervised methods, self-supervised learning methods learn representations without relying on annotated data. That is well-suited for genomics, where high throughput sequencing techniques can create potentially large amounts of unlabeled data. Some examples of self-supervised learning methods applied on genomics include DNABERT and Self-GenomeNet.[19][20]

Random forest

Random forests (RF) classify by constructing an ensemble of decision trees, and outputting the average prediction of the individual trees.[21] This is a modification of bootstrap aggregating (which aggregates a large collection of decision trees) and can be used for classification or regression.[22][23]

As random forests give an internal estimate of generalization error, cross-validation is unnecessary. In addition, they produce proximities, which can be used to impute missing values, and which enable novel data visualizations.[24]

Computationally, random forests are appealing because they naturally handle both regression and (multiclass) classification, are relatively fast to train and to predict, depend only on one or two tuning parameters, have a built-in estimate of the generalization error, can be used directly for high-dimensional problems, and can easily be implemented in parallel. Statistically, random forests are appealing for additional features, such as measures of variable importance, differential class weighting, missing value imputation, visualization, outlier detection, and unsupervised learning.[24]

Clustering

Clustering - the partitioning of a data set into disjoint subsets, so that the data in each subset are as close as possible to each other and as distant as possible from data in any other subset, according to some defined distance or similarity function - is a common technique for statistical data analysis.

Clustering is central to much data-driven bioinformatics research and serves as a powerful computational method whereby means of hierarchical, centroid-based, distribution-based, density-based, and self-organizing maps classification, has long been studied and used in classical machine learning settings. Particularly, clustering helps to analyze unstructured and high-dimensional data in the form of sequences, expressions, texts, images, and so on. Clustering is also used to gain insights into biological processes at the genomic level, e.g. gene functions, cellular processes, subtypes of cells, gene regulation, and metabolic processes.[25]

Clustering algorithms used in bioinformatics

Data clustering algorithms can be hierarchical or partitional. Hierarchical algorithms find successive clusters using previously established clusters, whereas partitional algorithms determine all clusters at once. Hierarchical algorithms can be agglomerative (bottom-up) or divisive (top-down).

Agglomerative algorithms begin with each element as a separate cluster and merge them in successively larger clusters. Divisive algorithms begin with the whole set and proceed to divide it into successively smaller clusters. Hierarchical clustering is calculated using metrics on Euclidean spaces, the most commonly used is the Euclidean distance computed by finding the square of the difference between each variable, adding all the squares, and finding the square root of the said sum. An example of a hierarchical clustering algorithm is BIRCH, which is particularly good on bioinformatics for its nearly linear time complexity given generally large datasets.[26] Partitioning algorithms are based on specifying an initial number of groups, and iteratively reallocating objects among groups to convergence. This algorithm typically determines all clusters at once. Most applications adopt one of two popular heuristic methods: k-means algorithm or k-medoids. Other algorithms do not require an initial number of groups, such as affinity propagation. In a genomic setting this algorithm has been used both to cluster biosynthetic gene clusters in gene cluster families(GCF) and to cluster said GCFs.[27]

Workflow

Typically, a workflow for applying machine learning to biological data goes through four steps:[2]

- Recording, including capture and storage. In this step, different information sources may be merged into a single set.

- Preprocessing, including cleaning and restructuring into a ready-to-analyze form. In this step, uncorrected data are eliminated or corrected, while missing data maybe imputed and relevant variables chosen.

- Analysis, evaluating data using either supervised or unsupervised algorithms. The algorithm is typically trained on a subset of data, optimizing parameters, and evaluated on a separate test subset.

- Visualization and interpretation, where knowledge is represented effectively using different methods to assess the significance and importance of the findings.

Data errors

- Duplicate data is a significant issue in bioinformatics. Publicly available data may be of uncertain quality.[28]

- Errors during experimentation.[28]

- Erroneous interpretation.[28]

- Typing mistakes.[28]

- Non-standardized methods (3D structure in PDB from multiple sources, X-ray diffraction, theoretical modeling, nuclear magnetic resonance, etc.) are used in experiments.[28]

Applications

In general, a machine learning system can usually be trained to recognize elements of a certain class given sufficient samples.[29] For example, machine learning methods can be trained to identify specific visual features such as splice sites.[30]

Support vector machines have been extensively used in cancer genomic studies.[31] In addition, deep learning has been incorporated into bioinformatic algorithms. Deep learning applications have been used for regulatory genomics and cellular imaging.[32] Other applications include medical image classification, genomic sequence analysis, as well as protein structure classification and prediction.[33] Deep learning has been applied to regulatory genomics, variant calling and pathogenicity scores.[34] Natural language processing and text mining have helped to understand phenomena including protein-protein interaction, gene-disease relation as well as predicting biomolecule structures and functions.[35]

Precision/personalized medicine

Natural language processing algorithms personalized medicine for patients who suffer genetic diseases, by combining the extraction of clinical information and genomic data available from the patients. Institutes such as Health-funded Pharmacogenomics Research Network focus on finding breast cancer treatments.[36]

Precision medicine considers individual genomic variability, enabled by large-scale biological databases. Machine learning can be applied to perform the matching function between (groups of patients) and specific treatment modalities.[37]

Computational techniques are used to solve other problems, such as efficient primer design for PCR, biological-image analysis and back translation of proteins (which is, given the degeneration of the genetic code, a complex combinatorial problem).[2]

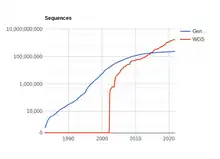

Genomics

While genomic sequence data has historically been sparse due to the technical difficulty of sequencing a piece of DNA, the number of available sequences is growing exponentially.[38] However, while raw data is becoming increasingly available and accessible, biological interpretation of this data is occurring at a much slower pace.[39] This makes for an increasing need for developing computational genomics tools, including machine learning systems, that can automatically determine the location of protein-encoding genes within a given DNA sequence (i.e. gene prediction).[39]

Gene prediction is commonly performed through both extrinsic searches and intrinsic searches.[39] For the extrinsic search, the input DNA sequence is run through a large database of sequences whose genes have been previously discovered and their locations annotated and identifying the target sequence's genes by determining which strings of bases within the sequence are homologous to known gene sequences. However, not all the genes in a given input sequence can be identified through homology alone, due to limits in the size of the database of known and annotated gene sequences. Therefore, an intrinsic search is needed where a gene prediction program attempts to identify the remaining genes from the DNA sequence alone.[39]

Machine learning has also been used for the problem of multiple sequence alignment which involves aligning many DNA or amino acid sequences in order to determine regions of similarity that could indicate a shared evolutionary history.[2] It can also be used to detect and visualize genome rearrangements.[40]

Proteomics

Proteins, strings of amino acids, gain much of their function from protein folding, where they conform into a three-dimensional structure, including the primary structure, the secondary structure (alpha helices and beta sheets), the tertiary structure, and the quaternary structure.

Protein secondary structure prediction is a main focus of this subfield as tertiary and quaternary structures are determined based on the secondary structure.[4] Solving the true structure of a protein is expensive and time-intensive, furthering the need for systems that can accurately predict the structure of a protein by analyzing the amino acid sequence directly.[4][2] Prior to machine learning, researchers needed to conduct this prediction manually. This trend began in 1951 when Pauling and Corey released their work on predicting the hydrogen bond configurations of a protein from a polypeptide chain.[41] Automatic feature learning reaches an accuracy of 82-84%.[4][42] The current state-of-the-art in secondary structure prediction uses a system called DeepCNF (deep convolutional neural fields) which relies on the machine learning model of artificial neural networks to achieve an accuracy of approximately 84% when tasked to classify the amino acids of a protein sequence into one of three structural classes (helix, sheet, or coil).[42] The theoretical limit for three-state protein secondary structure is 88–90%.[4]

Machine learning has also been applied to proteomics problems such as protein side-chain prediction, protein loop modeling, and protein contact map prediction.[2]

Metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of microbial communities from environmental DNA samples.[43] Currently, limitations and challenges predominate in the implementation of machine learning tools due to the amount of data in environmental samples.[44] Supercomputers and web servers have made access to these tools easier.[45] The high dimensionality of microbiome datasets is a major challenge in studying the microbiome; this significantly limits the power of current approaches for identifying true differences and increases the chance of false discoveries.[46]

Despite their importance, machine learning tools related to metagenomics have focused on the study of gut microbiota and the relationship with digestive diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), colorectal cancer and diabetes, seeking better diagnosis and treatments.[45] Many algorithms were developed to classify microbial communities according to the health condition of the host, regardless of the type of sequence data, e.g. 16S rRNA or whole-genome sequencing (WGS), using methods such as least absolute shrinkage and selection operator classifier, random forest, supervised classification model, and gradient boosted tree model. Neural networks, such as recurrent neural networks (RNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), and Hopfield neural networks have been added.[45] For example, in 2018, Fioravanti et al. developed an algorithm called Ph-CNN to classify data samples from healthy patients and patients with IBD symptoms (to distinguish healthy and sick patients) by using phylogenetic trees and convolutional neural networks.[47]

In addition, random forest (RF) methods and implemented importance measures help in the identification of microbiome species that can be used to distinguish diseased and non-diseased samples. However, the performance of a decision tree and the diversity of decision trees in the ensemble significantly influence the performance of RF algorithms. The generalization error for RF measures how accurate the individual classifiers are and their interdependence. Therefore, the high dimensionality problems of microbiome datasets pose challenges. Effective approaches require many possible variable combinations, which exponentially increases the computational burden as the number of features increases.[46]

For microbiome analysis in 2020 Dang & Kishino[46] developed a novel analysis pipeline. The core of the pipeline is an RF classifier coupled with forwarding variable selection (RF-FVS), which selects a minimum-size core set of microbial species or functional signatures that maximize the predictive classifier performance. The framework combines:

- identifying a few significant features by a massively parallel forward variable selection procedure

- mapping the selected species on a phylogenetic tree, and

- predicting functional profiles by functional gene enrichment analysis from metagenomic 16S rRNA data.

They demonstrated performance by analyzing two published datasets from large-scale case-control studies:

- 16S rRNA gene amplicon data for C. difficile infection (CDI) and

- shotgun metagenomics data for human colorectal cancer (CRC).

The proposed approach improved the accuracy from 81% to 99.01% for CDI and from 75.14% to 90.17% for CRC.

The use of machine learning in environmental samples has been less explored, maybe because of data complexity, especially from WGS. Some works show that it is possible to apply these tools in environmental samples. In 2021 Dhungel et al.,[48] designed an R package called MegaR. This package allows working with 16S rRNA and whole metagenomic sequences to make taxonomic profiles and classification models by machine learning models. MegaR includes a comfortable visualization environment to improve the user experience. Machine learning in environmental metagenomics can help to answer questions related to the interactions between microbial communities and ecosystems, e.g. the work of Xun et al., in 2021[49] where the use of different machine learning methods offered insights on the relationship among the soil, microbiome biodiversity, and ecosystem stability.

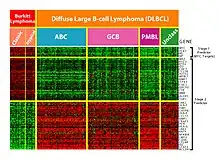

Microarrays

Microarrays, a type of lab-on-a-chip, are used for automatically collecting data about large amounts of biological material. Machine learning can aid in analysis, and has been applied to expression pattern identification, classification, and genetic network induction.[2]

This technology is especially useful for monitoring gene expression, aiding in diagnosing cancer by examining which genes are expressed.[50] One of the main tasks is identifying which genes are expressed based on the collected data.[2] In addition, due to the huge number of genes on which data is collected by the microarray, winnowing the large amount of irrelevant data to the task of expressed gene identification is challenging. Machine learning presents a potential solution as various classification methods can be used to perform this identification. The most commonly used methods are radial basis function networks, deep learning, Bayesian classification, decision trees, and random forest.[50]

Systems biology

Systems biology focuses on the study of emergent behaviors from complex interactions of simple biological components in a system. Such components can include DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites.[51]

Machine learning has been used to aid in modeling these interactions in domains such as genetic networks, signal transduction networks, and metabolic pathways.[2] Probabilistic graphical models, a machine learning technique for determining the relationship between different variables, are one of the most commonly used methods for modeling genetic networks.[2] In addition, machine learning has been applied to systems biology problems such as identifying transcription factor binding sites using Markov chain optimization.[2] Genetic algorithms, machine learning techniques which are based on the natural process of evolution, have been used to model genetic networks and regulatory structures.[2]

Other systems biology applications of machine learning include the task of enzyme function prediction, high throughput microarray data analysis, analysis of genome-wide association studies to better understand markers of disease, protein function prediction.[52]

Evolution

This domain, particularly phylogenetic tree reconstruction, uses the features of machine learning techniques. Phylogenetic trees are schematic representations of the evolution of organisms. Initially, they were constructed using features such as morphological and metabolic features. Later, due to the availability of genome sequences, the construction of the phylogenetic tree algorithm used the concept based on genome comparison. With the help of optimization techniques, a comparison was done by means of multiple sequence alignment.[53]

Stroke diagnosis

Machine learning methods for the analysis of neuroimaging data are used to help diagnose stroke. Historically multiple approaches to this problem involved neural networks.[54][55]

Multiple approaches to detect strokes used machine learning. As proposed by Mirtskhulava,[56] feed-forward networks were tested to detect strokes using neural imaging. As proposed by Titano[57] 3D-CNN techniques were tested in supervised classification to screen head CT images for acute neurologic events. Three-dimensional CNN and SVM methods are often used.[55]

Text mining

The increase in biological publications increased the difficulty in searching and compiling relevant available information on a given topic. This task is known as knowledge extraction. It is necessary for biological data collection which can then in turn be fed into machine learning algorithms to generate new biological knowledge.[2][58] Machine learning can be used for this knowledge extraction task using techniques such as natural language processing to extract the useful information from human-generated reports in a database. Text Nailing, an alternative approach to machine learning, capable of extracting features from clinical narrative notes was introduced in 2017.

This technique has been applied to the search for novel drug targets, as this task requires the examination of information stored in biological databases and journals.[58] Annotations of proteins in protein databases often do not reflect the complete known set of knowledge of each protein, so additional information must be extracted from biomedical literature. Machine learning has been applied to the automatic annotation of gene and protein function, determination of the protein subcellular localization, DNA-expression array analysis, large-scale protein interaction analysis, and molecule interaction analysis.[58]

Another application of text mining is the detection and visualization of distinct DNA regions given sufficient reference data.[59]

Clustering and abundance profiling of BGCs

Microbial communities are complex assembles of diverse microorganisms,[60] where symbiont partners constantly produce diverse metabolites derived from the primary and secondary (specialized) metabolism, from which metabolism plays an important role in microbial interaction.[61] Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data are an important source for deciphering communications signals.

Molecular mechanisms produce specialized metabolites in various ways. Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) attract attention, since several metabolites are clinically valuable, anti-microbial, anti-fungal, anti-parasitic, anti-tumor and immunosuppressive agents produced by the modular action of multi-enzymatic, multi-domains gene clusters, such as Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs).[62] Diverse studies[63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70] show that grouping BGCs that share homologous core genes into gene cluster families (GCFs) can yield useful insights into the chemical diversity of the analyzed strains, and can support linking BGCs to their secondary metabolites.[64][66] GCFs have been used as functional markers in human health studies[71][72] and to study the ability of soil to suppress fungal pathogens.[73] Given their direct relationship to catalytic enzymes, and compounds produced from their encoded pathways, BGCs/GCFs can serve as a proxy to explore the chemical space of microbial secondary metabolism. Cataloging GCFs in sequenced microbial genomes yields an overview of the existing chemical diversity and offers insights into future priorities.[63][65] Tools such as BiG-SLiCE and BIG-MAP[74] have emerged with the sole purpose of unveiling the importance of BGCs in natural environments.

BiG-SLiCE

BiG-SLiCE (Biosynthetic Genes Super-Linear Clustering Engine), is an automated pipeline tool designed to cluster massive numbers of BGCs. By representing them in euclidean space, BiG-SLiCE can group BGCs into GCFs in a non-pairwise, near-linear fashion.[75] from genomic and metagenomic data of diverse organisms.

The BiG-SLiCE workflow starts at vectorization (feature extraction), converting input BGCs provided from dataset of cluster GenBank files from antiSMASH and MIBiG into vectors of numerical features based on the absence/presence and bitscores of hits obtained from querying BGC gene sequences from a library curated of profile Hidden Markov Model[76](pHMMs) of biosynthetic domains of BGCs. Those features are then processed by a super-linear clustering algorithm based on BIRCH clustering,[26] resulting in centroid feature vectors representing the GCF models. All BGCs in the dataset are queried back against those models, outputting a list of GCF membership values for each BGC. Then a global cluster mapping is done using k-means to group all GCF centroid features in GCF bins. After that another round of membership assignment is performed to match the full set of BGC features into the resulting GCF bins. In the end, it produces archives, which then can be used to perform further analysis (via external scripts) or to visualize the result in a user-interactive application.

Satria et al.[75] demonstrated the utility of such analyses by reconstructing a global map of secondary metabolic diversity across taxonomy to identify the uncharted biosynthetic potential of 1.2 million biosynthetic gene clusters. This opens up new possibilities to accelerate natural product discovery and offers a first step towards constructing a global and searchable interconnected network of BGCs. As more genomes are sequenced from understudied taxa, more information can be mined to highlight their potentially novel chemistry.[75]

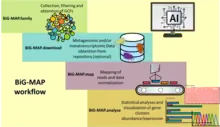

BiG-MAP

Since BGCs are an important source of metabolite production, current tools for identifying BGCs focus their efforts on mining genomes to identify their genomic landscape, neglecting relevant information about their abundance and expression levels which in fact, play an important ecological role in triggering phenotype dependent-metabolite concentration. That is why in 2020 BiG-MAP (Biosynthetic Gene cluster Meta’omics Abundance Profiler),[74] an automated pipeline that helps to determine the abundance (metagenomic data) and expression (metatranscriptomic data) of BGCs across microbial communities. It shotguns sequencing reads to gene clusters that have been predicted by antiSMASH or gutSMASH.

BiG-MAP splits its workflow in four main modules.

- BiG-MAP.family: redundancy filtering on the gene cluster collection in order to reduce computing time and avoid ambiguous mapping. Using a MinHash-based algorithm, MASH,[77] BiG-MAP estimates distance among protein sequences which then is used to select a representative gene cluster with the aid of k-medoids clustering. Finally, the selected gene clusters are clustered into GCFs using BiG-SCAPE,[63] considering account architectural similarity, thus relating more distantly related gene clusters which produce the same chemical product in different organisms

- BiG-MAP.download: optional module that uses a list of Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database;

- BiG-MAP.map: reads the set of representative GCFs obtained from the first module. Maps reads to GCFs separately and, it reports combined abundance or expression levels per family. Reads are mapped to the representative of the GCFs using the short-read aligner Bowtie2,[78] which are then converted into Reads Per Kilobase Million (RPKM) to be averaged over the GCFs size

- BiG-MAP.analyse: profiles abundance. RPKM values are normalized using Cumulative Sum Scaling[79] (CSS) to account for sparsity. Differential expressions analyses use zero-inflated Gaussian distribution mixture models (ZIG-models) or Kruskal-Wallis. The pipeline displays the results s plots that show gene cluster abundance/expression (heatmaps), log fold change (bar plot), coverage values, and housekeeping gene expression values for metatranscriptomic data (heatmap).

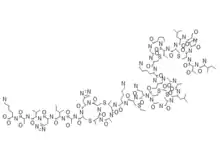

Decodification of RiPPs chemical structures

The increase of experimentally characterized ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), together with the availability of information on their sequence and chemical structure, selected from databases such as BAGEL, BACTIBASE, MIBIG, and THIOBASE, provide the opportunity to develop machine learning tools to decode the chemical structure and classify them.

In 2017, researchers at the National Institute of Immunology of New Delhi, India, developed RiPPMiner[80] software, a bioinformatics resource for decoding RiPP chemical structures by genome mining. The RiPPMiner web server consists of a query interface and the RiPPDB database. RiPPMiner defines 12 subclasses of RiPPs, predicting the cleavage site of the leader peptide and the final cross-link of the RiPP chemical structure.

Identification of RiPPs and prediction of RiPP Class

RiPPs analysis tools such as antiSMASH and RiPP-PRISM use HMM[76] of modifying enzymes present in biosynthetic gene clusters in RiPP to predict the RiPP subclass. Unlike these tools, RiPPMiner uses a machine learning model, trained with 513 RiPPs, that uses the amino acid sequence of the RiPP gene uniquely to identify and subclass them. RiPPMiner differentiates RiPPs from other proteins and peptides using a support-vector machine model trained on 293 experimentally characterized RiPPs as a positive data set, and 8140 genomes encoded non-RiPPs polypeptides as negative data set. The negative data set included SWISSProt entries similar in length to RiPPs, e.g., 30s ribosomal proteins, matrix proteins, cytochrome B proteins, etc. The support vectors consist of amino acid composition and dipeptide frequencies.

Benchmarking on an independent dataset (not included in training) using a two-fold cross-validation approach indicated sensitivity, specificity, precision and MCC values of 0.93, 0.90, 0.90, and 0.85, respectively. This indicates the model's predictive power for distinguishing between RiPPs and non-RiPPs. For prediction of RiPP class or sub-class, a Multi-Class SVM was trained using the amino acid composition and dipeptide frequencies as feature vectors. During the training of the Multi-Class SVM, available RiPP precursor sequences belonging to a given class (e.g. lasso peptide) were used as a positive set, while RiPPs belonging to all other classes were used as negative set.

Prediction of cleavage site

Out of the four major RiPP classes that had more than 50 experimentally characterized RiPPs in RiPPDB, SVM models for prediction of cleavage sites were developed for lanthipeptides, cyanobactins, and lasso peptides. In order to develop SVM for prediction of cleavage site for lanthipeptides, 12 mer peptide sequences centered on the cleavage sites were extracted from a set of 115 lanthipeptide precursor sequences with known cleavage pattern. This resulted in a positive dataset of 103 unique 12 mer peptides harboring the cleavage site at the center, while the other 12 constituted the negative dataset. Feature vectors for each of these mers consisted of the concatenation of 20-dimensional vectors corresponding to each of the 20 amino acids. An SVM model for prediction of cleavage site was developed and benchmarked using 2-fold cross-validation, where half of the data were used in training and the other half in testing. SVM models were developed for the prediction of the cleavage sites in cyanobactin and lasso peptides. Based on analysis of the ROC curves, a suitable score cutoff was chosen for the prediction of cleavage sites in lanthipeptides and lasso peptides.

Prediction of cross-links

The algorithm for the prediction of cross-links and deciphering the complete chemical structure of RiPP has been implemented for lanthipeptides, lasso peptides, cyanobactins, and thiopeptides. The prediction of lanthionine linkages in lanthipeptides was carried out using machine learning. A dataset of 93 lanthipeptides whose chemical structures was known was taken from RiPPDB. For each lanthipeptide in this set, the sequence of the core peptide was scanned for strings or sub-sequences of the type Ser/Thr-(X)n-Cys or Cys-(X)n-Ser/Thr to enumerate all theoretically possible cyclization patterns. Out of these sequence strings, the strings corresponding to Ser/Thr-Cys or Cys-Ser/Thr pairs which were linked by lanthionine bridges were included in the positive set, while all other strings were included in the negative set.

Mass spectral similarity scoring

Many tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) based metabolomics studies, such as library matching and molecular networking, use spectral similarity as a proxy for structural similarity. Spec2vec[81] algorithm provides a new way of spectral similarity score, based on Word2Vec. Spec2Vec learns fragmental relationships within a large set of spectral data, in order to assess spectral similarities between molecules and to classify unknown molecules through these comparisons.

For systemic annotation, some metabolomics studies rely on fitting measured fragmentation mass spectra to library spectra or contrasting spectra via network analysis. Scoring functions are used to determine the similarity between pairs of fragment spectra as part of these processes. So far, no research has suggested scores that are significantly different from the commonly utilized cosine-based similarity.[82]

Databases

An important part of bioinformatics is the management of big datasets, known as databases of reference. Databases exist for each type of biological data, for example for biosynthetic gene clusters and metagenomes.

National Center for Biotechnology Information

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[83] provides a large suite of online resources for biological information and data, including the GenBank nucleic acid sequence database and the PubMed database of citations and abstracts for published life science journals. Augmenting many of the Web applications are custom implementations of the BLAST program optimized to search specialized data sets. Resources include PubMed Data Management, RefSeq Functional Elements, genome data download, variation services API, Magic-BLAST, QuickBLASTp, and Identical Protein Groups. All of these resources can be accessed through NCBI.[84]

antiSMASH

antiSMASH allows the rapid genome-wide identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genomes. It integrates and cross-links with a large number of in silico secondary metabolite analysis tools.[85]

gutSMASH

gutSMASH is a tool that systematically evaluates bacterial metabolic potential by predicting both known and novel anaerobic metabolic gene clusters (MGCs) from the gut microbiome.

MIBiG

MIBiG,[86] the minimum information about a biosynthetic gene cluster specification, provides a standard for annotations and metadata on biosynthetic gene clusters and their molecular products. MIBiG is a Genomic Standards Consortium project that builds on the minimum information about any sequence (MIxS) framework.[87]

MIBiG facilitates the standardized deposition and retrieval of biosynthetic gene cluster data as well as the development of comprehensive comparative analysis tools. It empowers next-generation research on the biosynthesis, chemistry and ecology of broad classes of societally relevant bioactive secondary metabolites, guided by robust experimental evidence and rich metadata components.[88]

SILVA

SILVA[89] is an interdisciplinary project among biologists and computers scientists assembling a complete database of RNA ribosomal (rRNA) sequences of genes, both small (16S, 18S, SSU) and large (23S, 28S, LSU) subunits, which belong to the bacteria, archaea and eukarya domains. These data are freely available for academic and commercial use.[90]

Greengenes

Greengenes[91] is a full-length 16S rRNA gene database that provides chimera screening, standard alignment and a curated taxonomy based on de novo tree inference.[92][93] Overview:

- 1,012,863 RNA sequences from 92,684 organisms contributed to RNAcentral.

- The shortest sequence has 1,253 nucleotides, the longest 2,368.

- The average length is 1,402 nucleotides.

- Database version: 13.5.

Open Tree of Life Taxonomy

Open Tree of Life Taxonomy (OTT)[94] aims to build a complete, dynamic, and digitally available Tree of Life by synthesizing published phylogenetic trees along with taxonomic data. Phylogenetic trees have been classified, aligned, and merged. Taxonomies have been used to fill in sparse regions and gaps left by phylogenies. OTT is a base that has been little used for sequencing analyzes of the 16S region, however, it has a greater number of sequences classified taxonomically down to the genus level compared to SILVA and Greengenes. However, in terms of classification at the edge level, it contains a lesser amount of information[95]

References

- Chicco D (December 2017). "Ten quick tips for machine learning in computational biology". BioData Mining. 10 (35): 35. doi:10.1186/s13040-017-0155-3. PMC 5721660. PMID 29234465.

- Larrañaga P, Calvo B, Santana R, Bielza C, Galdiano J, Inza I, et al. (March 2006). "Machine learning in bioinformatics". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 7 (1): 86–112. doi:10.1093/bib/bbk007. PMID 16761367.

- Pérez-Wohlfeil E, Torrenoa O, Bellis LJ, Fernandes PL, Leskosek B, Trellesa O (December 2018). "Training bioinformaticians in High Performance Computing". Heliyon. 4 (12): e01057. Bibcode:2018Heliy...401057P. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01057. PMC 6299036. PMID 30582061.

- Yang Y, Gao J, Wang J, Heffernan R, Hanson J, Paliwal K, Zhou Y (May 2018). "Sixty-five years of the long march in protein secondary structure prediction: the final stretch?". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 19 (3): 482–494. doi:10.1093/bib/bbw129. PMC 5952956. PMID 28040746.

- Shastry KA, Sanjay HA (2020). "Machine Learning for Bioinformatics". In Srinivasa K, Siddesh G, Manisekhar S (eds.). Statistical Modelling and Machine Learning Principles for Bioinformatics Techniques, Tools, and Applications. Algorithms for Intelligent Systems. Singapore: Springer. pp. 25–39. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2445-5_3. ISBN 978-981-15-2445-5. S2CID 214350490. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- Soueidan H, Nikolski M (2019). "Machine learning for metagenomics: methods and tools". Metagenomics. 1. arXiv:1510.06621. doi:10.1515/metgen-2016-0001. ISSN 2449-7657. S2CID 17418188.

- Rabiner L, Juang B (January 1986). "An introduction to hidden Markov models". IEEE ASSP Magazine. 3 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1109/MASSP.1986.1165342. ISSN 1558-1284. S2CID 11358505.

- Jackson CH, Sharples LD, Thompson SG, Duffy SW, Couto E (July 2003). "Multistate Markov models for disease progression with classification error". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series D (The Statistician). 52 (2): 193–209. doi:10.1111/1467-9884.00351. S2CID 9824404.

- Amoros R, King R, Toyoda H, Kumada T, Johnson PJ, Bird TG (May 30, 2019). "A continuous-time hidden Markov model for cancer surveillance using serum biomarkers with application to hepatocellular carcinoma". Metron. 77 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1007/s40300-019-00151-8. PMC 6820468. PMID 31708595.

- Eddy SR (October 1, 1998). "Profile hidden Markov models". Bioinformatics. 14 (9): 755–63. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. PMID 9918945.

- McClintock BT, Langrock R, Gimenez O, Cam E, Borchers DL, Glennie R, Patterson TA (December 2020). "Uncovering ecological state dynamics with hidden Markov models". Ecology Letters. 23 (12): 1878–1903. arXiv:2002.10497. doi:10.1111/ele.13610. PMC 7702077. PMID 33073921.

- Zhang W (1988). "Shift-invariant pattern recognition neural network and its optical architecture". Proceedings of Annual Conference of the Japan Society of Applied Physics.

- Zhang W, Itoh K, Tanida J, Ichioka Y (November 1990). "Parallel distributed processing model with local space-invariant interconnections and its optical architecture". Applied Optics. 29 (32): 4790–7. Bibcode:1990ApOpt..29.4790Z. doi:10.1364/AO.29.004790. PMID 20577468.

- Fukushima K (2007). "Neocognitron". Scholarpedia. 2 (1): 1717. Bibcode:2007SchpJ...2.1717F. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.1717.

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN (March 1968). "Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex". The Journal of Physiology. 195 (1): 215–43. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008455. PMC 1557912. PMID 4966457.

- Fukushima K (1980). "Neocognitron: a self organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position". Biological Cybernetics. 36 (4): 193–202. doi:10.1007/BF00344251. PMID 7370364. S2CID 206775608.

- Matsugu M, Mori K, Mitari Y, Kaneda Y (2003). "Subject independent facial expression recognition with robust face detection using a convolutional neural network". Neural Networks. 16 (5–6): 555–9. doi:10.1016/S0893-6080(03)00115-1. PMID 12850007.

- Fioravanti D, Giarratano Y, Maggio V, Agostinelli C, Chierici M, Jurman G, Furlanello C (March 2018). "Phylogenetic convolutional neural networks in metagenomics". BMC Bioinformatics. 19 (Suppl 2): 49. doi:10.1186/s12859-018-2033-5. PMC 5850953. PMID 29536822.

- Ji, Yanrong; Zhou, Zhihan; Liu, Han; Davuluri, Ramana V (August 9, 2021). Kelso, Janet (ed.). "DNABERT: pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers model for DNA-language in genome". Bioinformatics. 37 (15): 2112–2120. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btab083. ISSN 1367-4803.

- Gündüz, Hüseyin Anil; Binder, Martin; To, Xiao-Yin; Mreches, René; Bischl, Bernd; McHardy, Alice C.; Münch, Philipp C.; Rezaei, Mina (September 11, 2023). "A self-supervised deep learning method for data-efficient training in genomics". Communications Biology. 6 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-05310-2. ISSN 2399-3642.

- Ho TK (1995). Random Decision Forests. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, 14–16 August 1995. pp. 278–282.

- Dietterich T (2000). An Experimental Comparison of Three Methodsfor Constructing Ensembles of Decision Trees:Bagging, Boosting, and Randomization. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 139–157.

- Breiman L (2001). Random Forest (45 ed.). Machine Learning: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 5–32.

- Zhang C, Ma Y (2012). Ensemble machine learning: methods and applications. New York: Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London. pp. 157–175. ISBN 978-1-4419-9325-0.

- Karim MR, Beyan O, Zappa A, Costa IG, Rebholz-Schuhmann D, Cochez M, Decker S (January 2021). "Deep learning-based clustering approaches for bioinformatics". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 22 (1): 393–415. doi:10.1093/bib/bbz170. PMC 7820885. PMID 32008043.

- Lorbeer B, Kosareva A, Deva B, Softić D, Ruppel P, Küpper A (March 1, 2018). "Variations on the Clustering Algorithm BIRCH". Big Data Research. 11: 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.bdr.2017.09.002.

- Navarro-Muñoz JC, Selem-Mojica N, Mullowney MW, Kautsar SA, Tryon JH, Parkinson EI, et al. (January 2020). "A computational framework to explore large-scale biosynthetic diversity". Nature Chemical Biology. 16 (1): 60–68. doi:10.1038/s41589-019-0400-9. PMC 6917865. PMID 31768033.

- Shastry KA, Sanjay HA (2020). "Machine Learning for Bioinformatics". Statistical Modelling and Machine Learning Principles for Bioinformatics Techniques, Tools, and Applications. Algorithms for Intelligent Systems. Springer Singapore. pp. 25–39. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2445-5_3. ISBN 978-981-15-2444-8. S2CID 214350490.

- Libbrecht MW, Noble WS (June 2015). "Machine learning applications in genetics and genomics". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 16 (6): 321–32. doi:10.1038/nrg3920. PMC 5204302. PMID 25948244.

- Degroeve S, De Baets B, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P (2002). "Feature subset selection for splice site prediction". Bioinformatics. 18 (Suppl 2): S75-83. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_2.s75. PMID 12385987.

- Huang S, Cai N, Pacheco PP, Narrandes S, Wang Y, Xu W (January 2018). "Applications of Support Vector Machine (SVM) Learning in Cancer Genomics". Cancer Genomics & Proteomics. 15 (1): 41–51. doi:10.21873/cgp.20063. PMC 5822181. PMID 29275361.

- Angermueller C, Pärnamaa T, Parts L, Stegle O (July 2016). "Deep learning for computational biology". Molecular Systems Biology. 12 (7): 878. doi:10.15252/msb.20156651. PMC 4965871. PMID 27474269.

- Cao C, Liu F, Tan H, Song D, Shu W, Li W, et al. (February 2018). "Deep Learning and Its Applications in Biomedicine". Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics. 16 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2017.07.003. PMC 6000200. PMID 29522900.

- Zou J, Huss M, Abid A, Mohammadi P, Torkamani A, Telenti A (January 2019). "A primer on deep learning in genomics". Nature Genetics. 51 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0295-5. PMID 30478442. S2CID 205572042.

- Zeng Z, Shi H, Wu Y, Hong Z (2015). "Survey of Natural Language Processing Techniques in Bioinformatics". Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2015 (D1): 674296. doi:10.1155/2015/674296. PMC 4615216. PMID 26525745.

- Zeng Z, Shi H, Wu Y, Hong Z (2012). "Survey of Natural Language Processing Techniques in Bioinformatics". Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2015 (D1): 674296. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385467-4.00006-3. PMC 4615216. PMID 26525745.

- Zeng Z, Shi H, Wu Y, Hong Z (2017). "Survey of Natural Language Processing Techniques in Bioinformatics". Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2015 (D1): 674296. doi:10.1155/2015/674296. PMC 4615216. PMID 26525745.

- "GenBank and WGS Statistics". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- Mathé C, Sagot MF, Schiex T, Rouzé P (October 2002). "Current methods of gene prediction, their strengths and weaknesses". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (19): 4103–17. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf543. PMC 140543. PMID 12364589.

- Pratas D, Silva RM, Pinho AJ, Ferreira PJ (May 2015). "An alignment-free method to find and visualise rearrangements between pairs of DNA sequences". Scientific Reports. 5 (10203): 10203. Bibcode:2015NatSR...510203P. doi:10.1038/srep10203. PMC 4434998. PMID 25984837.

- Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR (April 1951). "The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 37 (4): 205–11. Bibcode:1951PNAS...37..205P. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. PMC 1063337. PMID 14816373.

- Wang S, Peng J, Ma J, Xu J (January 2016). "Protein Secondary Structure Prediction Using Deep Convolutional Neural Fields". Scientific Reports. 6: 18962. arXiv:1512.00843. Bibcode:2016NatSR...618962W. doi:10.1038/srep18962. PMC 4707437. PMID 26752681.

- Riesenfeld CS, Schloss PD, Handelsman J (2004). "Metagenomics: genomic analysis of microbial communities". Annual Review of Genetics. 38 (1): 525–52. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091216. PMID 15568985.

- Soueidan H, Nikolski M (March 8, 2016). "Machine learning for metagenomics: methods and tools". arXiv:1510.06621 [q-bio.GN].

- Lin Y, Wang G, Yu J, Sung JJ (April 2021). "Artificial intelligence and metagenomics in intestinal diseases". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 36 (4): 841–847. doi:10.1111/jgh.15501. PMID 33880764. S2CID 233312307.

- Dang T, Kishino H (January 2020). "Detecting significant components of microbiomes by random forest with forward variable selection and phylogenetics". bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.10.29.361360.

- Fioravanti D, Giarratano Y, Maggio V, Agostinelli C, Chierici M, Jurman G, Furlanello C (March 2018). "Phylogenetic convolutional neural networks in metagenomics". BMC Bioinformatics. 19 (Suppl 2): 49. doi:10.1186/s12859-018-2033-5. PMC 5850953. PMID 29536822.

- Dhungel E, Mreyoud Y, Gwak HJ, Rajeh A, Rho M, Ahn TH (January 2021). "MegaR: an interactive R package for rapid sample classification and phenotype prediction using metagenome profiles and machine learning". BMC Bioinformatics. 22 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s12859-020-03933-4. PMC 7814621. PMID 33461494.

- Xun W, Liu Y, Li W, Ren Y, Xiong W, Xu Z, et al. (January 2021). "Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability". Microbiome. 9 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00985-9. PMC 7849160. PMID 33517892.

- Pirooznia M, Yang JY, Yang MQ, Deng Y (2008). "A comparative study of different machine learning methods on microarray gene expression data". BMC Genomics. 9 Suppl 1 (1): S13. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-S1-S13. PMC 2386055. PMID 18366602.

- "Machine Learning in Molecular Systems Biology". Frontiers. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- d'Alché-Buc F, Wehenkel L (December 2008). "Machine learning in systems biology". BMC Proceedings. 2 Suppl 4 (4): S1. doi:10.1186/1753-6561-2-S4-S1. PMC 2654969. PMID 19091048.

- Bhattacharya M (2020). "Unsupervised Techniques in Genomics". In Srinivasa MG, Siddesh GM, MAnisekhar SR (eds.). Statistical Modelling and Machine Learning Principles for Bioinformatics Techniques, Tools, and Applications. Springer Singapore. pp. 164–188. ISBN 978-981-15-2445-5.

- Topol EJ (January 2019). "High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence". Nature Medicine. 25 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7. PMID 30617339. S2CID 57574615.

- Jiang F, Jiang Y, Zhi H, Dong Y, Li H, Ma S, et al. (December 2017). "Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future". Stroke and Vascular Neurology. 2 (4): 230–243. doi:10.1136/svn-2017-000101. PMC 5829945. PMID 29507784.

- Mirtskhulava L, Wong J, Al-Majeed S, Pearce G (March 2015). "Artificial Neural Network Model in Stroke Diagnosis" (PDF). 2015 17th UKSim-AMSS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation (UKSim). pp. 50–53. doi:10.1109/UKSim.2015.33. ISBN 978-1-4799-8713-9. S2CID 6391733.

- Titano JJ, Badgeley M, Schefflein J, Pain M, Su A, Cai M, et al. (September 2018). "Automated deep-neural-network surveillance of cranial images for acute neurologic events". Nature Medicine. 24 (9): 1337–1341. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0147-y. PMID 30104767. S2CID 51976344.

- Krallinger M, Erhardt RA, Valencia A (March 2005). "Text-mining approaches in molecular biology and biomedicine". Drug Discovery Today. 10 (6): 439–45. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03376-3. PMID 15808823.

- Pratas D, Hosseini M, Silva R, Pinho A, Ferreira P (June 20–23, 2017). "Visualization of Distinct DNA Regions of the Modern Human Relatively to a Neanderthal Genome". Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10255. pp. 235–242. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58838-4_26. ISBN 978-3-319-58837-7.

- Bardgett RD, Caruso T (March 2020). "Soil microbial community responses to climate extremes: resistance, resilience and transitions to alternative states". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 375 (1794): 20190112. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0112. PMC 7017770. PMID 31983338.

- Deveau A, Bonito G, Uehling J, Paoletti M, Becker M, Bindschedler S, et al. (May 2018). "Bacterial-fungal interactions: ecology, mechanisms and challenges". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 42 (3): 335–352. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuy008. PMID 29471481.

- Ansari MZ, Yadav G, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D (July 2004). "NRPS-PKS: a knowledge-based resource for analysis of NRPS/PKS megasynthases". Nucleic Acids Research. 32 (Web Server issue): W405-13. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh359. PMC 441497. PMID 15215420.

- Navarro-Muñoz JC, Selem-Mojica N, Mullowney MW, Kautsar SA, Tryon JH, Parkinson EI, et al. (January 2020). "A computational framework to explore large-scale biosynthetic diversity". Nature Chemical Biology. 16 (1): 60–68. doi:10.1038/s41589-019-0400-9. PMC 6917865. PMID 31768033.

- Doroghazi JR, Albright JC, Goering AW, Ju KS, Haines RR, Tchalukov KA, et al. (November 2014). "A roadmap for natural product discovery based on large-scale genomics and metabolomics". Nature Chemical Biology. 10 (11): 963–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1659. PMC 4201863. PMID 25262415.

- Cimermancic P, Medema MH, Claesen J, Kurita K, Wieland Brown LC, Mavrommatis K, et al. (July 2014). "Insights into secondary metabolism from a global analysis of prokaryotic biosynthetic gene clusters". Cell. 158 (2): 412–421. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034. PMC 4123684. PMID 25036635.

- Goering AW, McClure RA, Doroghazi JR, Albright JC, Haverland NA, Zhang Y, et al. (February 2016). "Metabologenomics: Correlation of Microbial Gene Clusters with Metabolites Drives Discovery of a Nonribosomal Peptide with an Unusual Amino Acid Monomer". ACS Central Science. 2 (2): 99–108. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.5b00331. PMC 4827660. PMID 27163034.

- Amiri Moghaddam J, Crüsemann M, Alanjary M, Harms H, Dávila-Céspedes A, Blom J, et al. (November 2018). "Analysis of the Genome and Metabolome of Marine Myxobacteria Reveals High Potential for Biosynthesis of Novel Specialized Metabolites". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 16600. Bibcode:2018NatSR...816600A. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-34954-y. PMC 6226438. PMID 30413766.

- Duncan KR, Crüsemann M, Lechner A, Sarkar A, Li J, Ziemert N, et al. (April 2015). "Molecular networking and pattern-based genome mining improves discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters and their products from Salinispora species". Chemistry & Biology. 22 (4): 460–471. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.010. PMC 4409930. PMID 25865308.

- Nielsen JC, Grijseels S, Prigent S, Ji B, Dainat J, Nielsen KF, et al. (April 2017). "Global analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters reveals vast potential of secondary metabolite production in Penicillium species". Nature Microbiology. 2 (6): 17044. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.44. PMID 28368369. S2CID 22699928.

- McClure RA, Goering AW, Ju KS, Baccile JA, Schroeder FC, Metcalf WW, et al. (December 2016). "Elucidating the Rimosamide-Detoxin Natural Product Families and Their Biosynthesis Using Metabolite/Gene Cluster Correlations". ACS Chemical Biology. 11 (12): 3452–3460. doi:10.1021/acschembio.6b00779. PMC 5295535. PMID 27809474.

- Cao L, Shcherbin E, Mohimani H (August 2019). "A Metabolome- and Metagenome-Wide Association Network Reveals Microbial Natural Products and Microbial Biotransformation Products from the Human Microbiota". mSystems. 4 (4): e00387–19, /msystems/4/4/msys.00387–19.atom. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00387-19. PMC 6712304. PMID 31455639.

- Olm MR, Bhattacharya N, Crits-Christoph A, Firek BA, Baker R, Song YS, et al. (December 2019). "Necrotizing enterocolitis is preceded by increased gut bacterial replication, Klebsiella, and fimbriae-encoding bacteria". Science Advances. 5 (12): eaax5727. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.5727O. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5727. PMC 6905865. PMID 31844663.

- Carrión VJ, Perez-Jaramillo J, Cordovez V, Tracanna V, de Hollander M, Ruiz-Buck D, et al. (November 2019). "Pathogen-induced activation of disease-suppressive functions in the endophytic root microbiome". Science. 366 (6465): 606–612. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..606C. doi:10.1126/science.aaw9285. PMID 31672892. S2CID 207814746.

- Andreu VP, Augustijn HE, van den Berg K, van der Hooft JJ, Fischbach MA, Medema MH (December 15, 2020). "BiG-MAP: an automated pipeline to profile metabolic gene cluster abundance and expression in microbiomes". bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.12.14.422671.

- Kautsar SA, van der Hooft JJ, de Ridder D, Medema MH (January 2021). "BiG-SLiCE: A highly scalable tool maps the diversity of 1.2 million biosynthetic gene clusters". GigaScience. 10 (1): giaa154. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giaa154. PMC 7804863. PMID 33438731.

- Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, et al. (July 2011). "antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Web Server issue): W339-46. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr466. PMC 3125804. PMID 21672958.

- Ondov BD, Treangen TJ, Melsted P, Mallonee AB, Bergman NH, Koren S, Phillippy AM (June 2016). "Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash". Genome Biology. 17 (1): 132. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x. PMC 4915045. PMID 27323842.

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (March 2012). "Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2". Nature Methods. 9 (4): 357–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1923. PMC 3322381. PMID 22388286.

- "CSS - Metagenomics". metagenomics.wiki.

- Agrawal P, Khater S, Gupta M, Sain N, Mohanty D (July 2017). "RiPPMiner: a bioinformatics resource for deciphering chemical structures of RiPPs based on prediction of cleavage and cross-links". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (W1): W80–W88. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx408. PMC 5570163. PMID 28499008.

- Huber F, Ridder L, Verhoeven S, Spaaks JH, Diblen F, Rogers S, van der Hooft JJ (February 2021). "Spec2Vec: Improved mass spectral similarity scoring through learning of structural relationships". PLOS Computational Biology. 17 (2): e1008724. Bibcode:2021PLSCB..17E8724H. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008724. PMC 7909622. PMID 33591968.

- Huber F, Ridder L, Verhoeven S, Spaaks JH, Diblen F, Rogers S, van der Hooft JJ (February 2021). "Spec2Vec: Improved mass spectral similarity scoring through learning of structural relationships". PLOS Computational Biology. 17 (2): e1008724. Bibcode:2021PLSCB..17E8724H. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008724. PMC 7909622. PMID 33591968.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information; U.S. National Library of Medicine. "National Center for Biotechnology Information". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- Agarwala R, Barrett T, Beck J, Benson DA, Bollin C, Bolton E, et al. (NCBI Resource Coordinators) (January 2018). "Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (D1): D8–D13. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1095. PMC 5753372. PMID 29140470.

- "antiSMASH database". antismash-db.secondarymetabolites.org.

- "MIBiG: Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster". mibig.secondarymetabolites.org. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- MiBiG

- Kautsar SA, Blin K, Shaw S, Navarro-Muñoz JC, Terlouw BR, van der Hooft JJ, et al. (January 2020). "MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (D1): D454–D458. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz882. PMC 7145714. PMID 31612915.

- "Silva". arb-silva.de. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. (January 2013). "The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (Database issue): D590-6. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1219. PMC 3531112. PMID 23193283.

- "greengenes.secondgenome.com". greengenes.secondgenome.com. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, et al. (July 2006). "Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (7): 5069–72. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.5069D. doi:10.1128/AEM.03006-05. PMC 1489311. PMID 16820507.

- McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, et al. (March 2012). "An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea". The ISME Journal. 6 (3): 610–8. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.139. PMC 3280142. PMID 22134646.

- "opentree". tree.opentreeoflife.org. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- Hinchliff CE, Smith SA, Allman JF, Burleigh JG, Chaudhary R, Coghill LM, et al. (October 2015). "Synthesis of phylogeny and taxonomy into a comprehensive tree of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (41): 12764–9. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11212764H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423041112. PMC 4611642. PMID 26385966.

- "RDP Release 11 -- Sequence Analysis Tools". rdp.cme.msu.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y, et al. (January 2014). "Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D633-42. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1244. PMC 3965039. PMID 24288368.