Sustainable landscape architecture

Sustainable landscape architecture is a category of sustainable design concerned with the planning and design of the built and natural environments.[1][2]

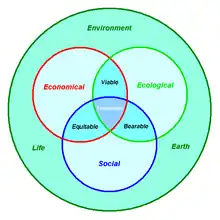

The design of a sustainable landscape encompasses the three pillars of sustainable development: economic well-being, social equity and environmental protections. The United Cities and Local Governments, UNESCO, and the World Summit on Sustainable Development further recommend including a fourth pillar of cultural preservation to create successful sustainable landscape designs.[3][4] Creating a sustainable landscape requires consideration of ecology, history, cultural associations, sociopolitical dynamics, geology, topography, soils, land use, and architecture.[5] Methods used to create sustainable landscapes include recycling, restoration, species reintroduction, and many more.[6]

Goals of sustainable landscape architecture include a reduction of pollution, heightened water management and thoughtful vegetation choices.[5]

An example of sustainable landscape architecture is the design of a sustainable urban drainage system, which can protect wildlife habitats, improve recreational facilities and save money through flood control. Another example is the design of a green roof or a roof garden that also contributes to the sustainability of a landscape architecture project. The roof will help manage surface water, decrease environmental impacts and provide space for recreation.

History

The first documented concern of the destruction of the modern landscape was in the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act.[7]

Historic Cultural Influences

Perspectives on what entails a sustainable landscape design vary in different cultural lenses.[8] Historically, Eastern and Western civilizations have had opposing philosophies of how to interact with nature within the built environment.[9]

United States

In the United States, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) acted as a pioneer in American landscape architecture.[10] Olmsted began his career as an agricultural correspondent, before visiting England where he experienced and brought back ideas of English landscape design to the United States. He used landscape design to transform societal dynamics. His projects encouraged the mingling of community members from different strata by creating communal passageways through the city. This fostered an emphasis on creating socially sustainable communal urban spaces. His legacy is still lived in projects such as New York City’s Central Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace and the U.S. Capitol Grounds.[11] The cultural and philosophical doctrine that Olmsted introduced to North American landscape architecture created a basis of socially sustainable landscape designs.[12] This idea falls under the old paradigm (1905-1940s) of scientific ecology, fathered by Frederic Clements, which excludes humans from being a part of natural ecology.[8] This school of thought sees nature as a venue for humans to mingle and interact, rather than including humans as part of the natural world and ecosystem. The next scientific ecology paradigm in American culture was the thermodynamic paradigm (1930s-1980s), most famously documented by Eugene Odum. Rather than seeing humans dominating and existing separate from ecology, this school of thought focused on the relationship between humanity and nature. This era was characterized by the New Deal in the United States, and projects such as the Tennessee Valley Authority and large-scale highway projects. Within this paradigm, the United States government began to foster support of natural conservation, inviting the public to travel and admire the conserved landscapes of the country.[8] However, efforts of conservatism within this age are criticized for emphasizing the human component of landscapes. The TVA, for example, championed the creation of dams and the production of energy. This created a space for admiration of a landscape altered solely for human benefit. Although there is a clear connection between humanity and nature, the emphasis on human accomplishment continued the anthropocentric culture of landscape architecture in North America. Within this same era, Ian McHarg was a leading landscape architect, and is seen as one of the first to challenge traditional ideas of landscape architecture towards a more sustainable lens. McHarg emphasized the idea of designing with nature, instead of against it. He encouraged thorough analysis and observation of a landscape before designing.[13] His ideas were revolutionary as he put the environmental restrictions at the forefront of landscape architecture, reasoning that a healthy living environment fosters occupant respect for their surroundings.[8] Instead of seeing man and nature as forces against one another, McHarg sought to bring them together.[9] Aldo Leopold was another influential figure during this time, who pushed for the symbiotic relationship between man and nature. In addition to Olmsted’s emphasis on societal equality within the space of designed landscape, Leopold urged society to view the landscapes as part of the community. The widespread government support of natural conservation in American culture began to shatter once economic growth and political unrest began to overwhelm the country.[8] These tensions gave way to the modern-day paradigm of scientific ecology: the evolutionary paradigm. This perspective views humans as a piece within nature’s dynamics, emphasizing the consequences of human impact on the environment.

Europe

European culture offers similar influences to the practice of sustainable landscape architecture. Western European countries would historically use landscaping to separate and organize natural habitats.[14] Like North American practices, conservation of nature was routinely seen as “management” of wildlife by containing it in a space that is admired from a distance. Furthermore, landscapes have been designed to optimize the use of natural resources and economic gain of the land. Research into landscapes of ancient Eastern European civilizations showed similar ideals. In the Aegean, coaxial field and terraces were frequently used to cultivate the land for food.[15] This connects to the root of all artificial landscape manipulation; a method of survival. Agriculture and resource allocation are an instinctual way which humans approach landscape architecture, demonstrating human dependence on continued and sustainable use of such landscapes.

Eastern Civilization

East Asian countries had a different cultural history in connection to sustainable landscape architecture. Whereas Western civilization focused on a human-centered built environment, Eastern countries used traditional philosophies that encourage the “unity of man and nature” to design landscapes.[9] This idea is centered around the Chinese philosophy of Taoism, claiming that humans must be in tune with nature’s rhythms.[9]

Instead of altering the environment to benefit humanity, this philosophy states that humans should create the build environment by taking advantage of natural patterns and tendencies (4). Furthermore, this school of thought considers The Peach Blossom Spring ideal, which expresses the cultural desire for nature to be a healing oasis for humans. In Eastern culture, nature is the overpowering entity that can care for humanity. This key difference from Western culture influenced a different trajectory of sustainable landscape architecture in Eastern civilization. The first instances of preservation and respect of nature was seen up to 2,000 years ago, via Chinese “gardens of literati”, or scholar gardens.[9] Landscapes like these emphasized controlled borders of landscape design, rather than growth and expansion. Furthermore, ideas of Yin-yang and Feng shui inspired sustainable landscape practices. Yin-yang emphasizes balance, and within the built environment, dictates that natural and manmade components of landscape architecture must be in harmony. Feng shui originates from traditional burial design, and represents the “wind-water” balance. This relationship represents a fluidity of ecological processes and Feng shui aims to protect these natural cycles. Additionally, Feng shui focuses on “Qi” energy of design components, and how this energy can be influenced to inspire the ideal symbiosis between human and nature. Qi can include any resource, such as clean air, water, and suitable soil.[6] Finding a location with Qi and maintaining the integrity of the Qi serves both the environment and the occupants. The principles defining Feng shui divide land into categories of which direction they face, their size, shape, and other parameters that dictate their “qi”, or energy potential. If the balance of a landscape does not cultivate optimal energy, to benefit both the ecosystem and humanity, then sustainable landscape architecture permits “bibo” or “apseung” - an addition or deletion, respectively - of materials. Human intervention therefore, is only used when necessary to increase the symbiosis of a landscape, rather than used simply to benefit human occupants of the area. The most influential aspect of Feng shui is its assessment of the built environment. Instead of quantitatively measuring the well-being of a community’s environment, the environment is assessed based on how it serves the culture, and if processes are in balance. This integrates the ecological well-being with cultural well-being, raising the stakes of the landscape health and connecting it directly to the people. Although Eastern culture emphasizes a harmonious and mutual benefit in humanity’s relationship with nature, critics point out that Eastern culture tends to emphasize landscape design on beauty, rather than function.[9]

Main Differences Between Western and Eastern Civilizations

The cultural backgrounds that give way to sustainable landscape architecture in the Western and Eastern hemisphere differ on several grounds. Western culture aimed to domesticate and tame nature.[16] Humans and nature were considered separate entities, and humans would design for ways to overcome the ‘obstacle’ of nature. Eastern culture, conversely, strived to be in harmony with nature.[9] Humans and nature were thought to be a part of the same cycle, and designs were created to be in sync with natural processes for maximum benefits. A specific phenomenon that exemplifies these two cultures is looking at building materials from the two contrasting cultures. In England and New England, whenever possible, brick and mortar were used, symbolic of the dominance that humans would exert in their built environment. These materials are strong, but energy intensive to make, and not in sync with the natural world. In China and other Asian countries, wood was the preferred building material, as it was readily available and renewable. Design of buildings and landscape were purposefully done in a way that enhances the flow of “Qi”, or energy, rather than stifling it.

Challenges to Sustainable Landscape Architecture

History and cultural norms have defined how landscape designs have been approached in the past, largely when interpreting how mankind can design untouched land. However, following the industrial revolution and along with a booming population rise, urbanization has become the main spotlight surrounding landscape architecture.[9] Some European countries have witnessed up to 80% of their population moving to urban centers.[17]

Along with these mass migrations comes a tremendous loss of biodiversity, as forest land is cleared for timber and residential land use.[18] Due to urbanization and increased transportation, neighboring rural landscapes and even remote villages have been delegated to functional urban regions (FURs) and are slowly losing their cultural and heritage value.[17] These patterns influence landscape architecture to be catered solely to urban spaces, and to serve the metropolitan needs of economic meccas. Whereas once culture was the driving force behind how sustainable landscape designs are, financial worth now governs the design of landscapes in a largely urban world. Instead of designing untouched land and choosing how to interact with nature, landscape architects face the challenge of how to design and renovate an environment or city to be as sustainable as possible.[19]

Western colonization of Eastern Asian countries has overwhelmed traditional cultural perspectives of landscape architecture with Western ideals. Urbanization leads to environmental degradation such as fragmentation, a lack of green spaces and poor water quality. All these side-effects hinder the practice of Fengshui.[6] For example, in Seoul, 20% of forests disappeared during urbanization in 1988-1999, due to an unplanned influx of population coupled with disorganization following the Korean War. To avoid the environmental downfalls of urbanization, methods such as planned spacing, sustainable transport systems and purposeful vegetation implementation (on roofs, roads, riversides) is recommended.[6]

.jpg.webp)

Due to a strong human presence and impact, sustainable landscape architecture is more important now than it has ever been.[9] Tools within the built environment, such as natural filters, climate control tactics and reconciliation ecology are recommended to sustain the planet. This requires a combination of both Eastern and Western cultural drivers. In Southern Europe, domestic species are being re-introduced to urbanized areas to help with cultural identity, food production, and a lack of vegetation in the city.[20] Athens is an example of this tactic. In the 1980s, Athens, Greece was a compact city. It slowly began to spread out into periphery farming land, consuming the landscapes bordering the urban space. The government has begun to plant olive trees in such areas, therefore benefitting from small green urban spaces in several categories. Olive trees offer cultural and traditional sustainability, due to their importance in Greek culture and history. They offer local food production and a source of income. Furthermore, the trees increase shade in heat island, and decrease the risk of fire. They are a low-maintenance crop which emphasizes sustainable landscape design within multiple realms, making their implementation a favorable way to design challenging urban landscapes in a sustainable fashion. The emphasis on the cultural identity of the olive trees ensures cultural sustainability, the suggested fourth pillar in sustainable development.

With urbanization and industrialization discouraging the participation in rural landscapes and communities, the United Nations has sought ways to restore culture sustainability with these spaces through touristic potential. In 1990, UNESCO emphasized the creation of GeoParks to instill geotourism and restore historical and cultural integrity to a site.[21] By rooting these projects in cultural incentives, landscape designs can focus on rural community ideals, rather than metropolitan restrictions. Ţara Haţegului in Romania is an ideal example of such a project which achieves sustainable landscape architecture by using cultural emphasis. Combining landscape architecture with cultural identity ensures that the land becomes a part of a community's heritage. The Council of Europe has created a framework convention on the value of cultural heritage, and they have concluded that cultural integrity correlates with social responsibility of a landscape.[22] They emphasize approaching landscape architecture in a conscious matter that protects people’s surrounding. By connecting people to their environment, it becomes part of their identity, and it gives motive to protect the ecosystem. The council concludes that such multidisciplinary policies are essential to cultivate sustainable landscape architecture.

Certifications

Green Business Certification Inc. has partnered with the U.S. Green Building Council to create the Sustainable SITES Initiative certification program.[23] This program has adopted LEED strategies in promoting the sustainability of landscapes within the built environment.

See also

- Built environment

- Carbon cycle re-balancing

- Climate-friendly gardening

- Context theory

- Cultural sustainability

- Energy-efficient landscaping

- Feng shui

- Frederick Law Olmsted

- Green roof

- Green transport

- GeoParks

- Ian McHarg

- Landscape planning

- Sustainable agriculture

- Sustainable gardening

- Sustainable landscaping

- Sustainable planting

- Sustainable urban drainage

- Urban agriculture

- Urban forestry

- Urbanization

- Taoism

References

- Orr, Stephen. "A Sustainability That Aims to Seduce". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- American Society of Landscape Architects. (2020). What is Landscape Architecture? Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.asla.org/aboutlandscapearchitecture.aspx Archived 2021-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Petrişor AI. (2014) GIS-Based Methodology for the Analysis of Regional Landscapes and Their Changes Based on Land Cover and Use: A Planning Perspective Aimed at Conserving the Natural Heritage. In: Crăciun C., Bostenaru Dan M. (eds) Planning and Designing Sustainable and Resilient Landscapes. Springer Geography. Springer, Dordrecht.

- United Cities and Local Governments (2010) Culture: fourth pillar of sustainable development. Policy statement. United Cities and Local Governments, Barcelona, Spain

- Bean, C., & Yang (Mayla), C. (2009, October). Standards in Sustainable Landscape Architecture. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://soa.utexas.edu/sites/default/disk/preliminary/preliminary/4-Bean_Yang-Standards_in_Sustainable_Landscape_Architecture.pdf Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Hong, SK., Song, IJ. & Wu, J. Fengshui theory in urban landscape planning. Urban Ecosyst 10, 221–237 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-006-3263-2 Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Tress, Bärbel; Tress, Barbel; Tres, Gunther; Fry, Gary; Opdam, Paul (2006). From Landscape Research to Landscape Planning: Aspects of Integration, Education and Application. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3979-9. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- Conan, M., & Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture. (2000). Environmentalism in Landscape Architecture.

- Chen, Xiangqiao, & Wu, Jianguo. (2009). Sustainable landscape architecture: Implications of the Chinese philosophy of “unity of man with nature” and beyond. Landscape Ecology, 24(8), 1015-1026.

- Nelson, G. D. (2015). Walking and talking through Walks and Talks: Traveling in the English landscape with Frederick Law Olmsted, 1850 and 2011. Journal of Historical Geography, 48, 47-57.

- The Cultural Landscape Foundation. (2020). Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://tclf.org/pioneer/frederick-law-olmsted-sr Archived 2021-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Kosnoski, J. (2011). Democratic Vistas: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Parks as Spatial Mediation of Urban Diversity. Space and Culture, 14(1), 51-66.

- The McHarg Center. (2019, August 13). Ian L. McHarg. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://mcharg.upenn.edu/ian-l-mcharg Archived 2021-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Angelstam, Per, Grodzynskyi, Michael, Andersson, Kjell, Axelsson, Robert, Elbakidze, Marine, Khoroshev, Alexander, . . . Naumov, Vladimir. (2013). Measurement, Collaborative Learning and Research for Sustainable Use of Ecosystem Services: Landscape Concepts and Europe as Laboratory. Ambio, 42(2), 129-145.

- Turner, Sam, & Crow, Jim. (2010). Unlocking historic landscapes in the Eastern Mediterranean: Two pilot studies using Historic Landscape Characterisation. Antiquity, 84(323), 216-229.

- Kareiva, P., Watts, S., Mcdonald, R., & Boucher, T. (2007). Domesticated Nature: Shaping Landscapes and Ecosystems for Human Welfare. Science, 316(5833), 1866-1869. doi:10.1126/science.1140170

- Antrop, M. (2004). Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. Landscape and Urban Planning, 67(1-4), 9-26. doi:10.1016/s0169-2046(03)00026-4

- Armaş I., Osaci-Costache G., Braşoveanu L. (2014) Forest Landscape History Using Diachronic Cartography and GIS. Case Study: Subcarpathian Prahova Valley, Romania. In: Crăciun C., Bostenaru Dan M. (eds) Planning and Designing Sustainable and Resilient Landscapes. Springer Geography. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Vasenev, V., Dovletyarova, Elvira., Chen, Zhongqi., Valentini, Riccardo., & International Conference on Landscape Architecture to Support City Sustainable Development. (2017). Megacities 2050 : Environmental Consequences of Urbanization : Proceedings of the VI International Conference on Landscape Architecture to Support City Sustainable Development.

- Cecchini, Massimo, Zambon, Ilaria, Pontrandolfi, Antonella, Turco, Rosario, Colantoni, Andrea, Mavrakis, Anastasios, & Salvati, Luca. (2018). Urban sprawl and the ‘olive’ landscape: Sustainable land management for ‘crisis’ cities. GeoJournal, 84(1), 237-255.

- Hărmănescu M. (2014) Living the Space from Ţara Haţegului: Building Places and Landscapes as Collective Identity and Memory. In: Crăciun C., Bostenaru Dan M. (eds) Planning and Designing Sustainable and Resilient Landscapes. Springer Geography. Springer, Dordrecht.

- European Landscape Convention, Mar. 1, 2004, ETS No. 176. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176 Archived 2021-06-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- GBCI. (2020). The Sustainable SITES Initiative. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from http://www.sustainablesites.org/about Archived 2021-08-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Landscape and sustainability John F. Benson, Maggie H. Roe (2007)

- Sustainable Site Design: Criteria, Process, and Case Studies Claudia Dinep, Kristin Schwab (2009)

- Sustainable urban design: perspectives and examples Work Group for Sustainable Urban Development (2005)

External links

- The Sustainable Landscapes Conference at Utah State University

- Information on designing a sustainable urban landscape

- Resource guides from the American society of landscape artists.