Visual design elements and principles

Visual design elements and principles describe fundamental ideas about the practice of visual design.

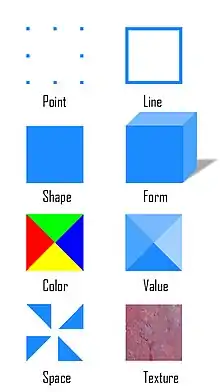

Elements of the design of the art

Design elements are the basic units of any visual design which form its structure and convey visual messages.[1][2] Painter and design theorist Maitland E. Graves (1902-1978), who attempted to gestate the fundamental principles of aesthetic order in visual design,[3] in his book, The Art of Color and Design (1941), defined the elements of design as line, direction, shape, size, texture, value, and color, concluding that "these elements are the materials from which all designs are built."[4]

.svg.png.webp)

Color

Color is the result of light reflecting back from an object to our eyes.[5] The color that our eyes perceive is determined by the pigment of the object itself.[5] Color theory and the color wheel are often referred to when studying color combinations in visual design.[6] Color is often deemed to be an important element of design as it is a universal language which presents the countless possibilities of visual communication.[7]

Hue, saturation, and brightness are the three characteristics that describe color.[8]

- Hue can simply be referred to as "color" as in red, yellow, or green.[9]

- Saturation gives a color brightness or dullness, which impacts the vibrance of the color.[9]

- Values, tints and shades of colors are created by adding black to a color for a shade and white for a tint. Creating a tint or shade of color reduces the saturation.[9]

Color theory in visual design

Color theory studies color mixing and color combinations. It is one of the first things that marked a progressive design approach.[7] In visual design, designers refer to color theory as a body of practical guidance to achieving certain visual impacts with specific color combinations. Theoretical color knowledge is implemented in designs in order to achieve a successful color design.[10]

Color harmony, often referred to as a "measure of aesthetics",[10] studies which color combinations are harmonious and pleasing to the eye, and which color combinations are not.[8] Color harmony is a main concern for designers given that colors always exist in the presence of other colors in form or space.[10]

When a designer harmonizes colors, the relationships among a set of colors are enhanced to increase the way they complement one another. Colors are harmonized to achieve a balanced, unified, and aesthetically pleasing effect for the viewer.[8]

Color harmony is achieved in a variety of ways, some of which consist of combining a set of colors that share the same hue, or a set of colors that share the same values for two of the three color characteristics (hue, saturation, brightness).[8] Color harmony can also be achieved by simply combining colors that are considered compatible to one another[8] as represented in the color wheel.

Color contrasts are studied with a pair of colors, as opposed to color harmony, which studies a set of colors. In color contrasting, two colors with perceivable differences in aspects such as luminance, or saturation, are placed side by side to create contrast.

Johannes Itten presented seven kinds of color contrasts: contrast of light and dark, contrast of hue, contrast of temperature, contrast of saturation, simultaneous contrast, contrast of sizes, and contrast of complementary.[8] These seven kinds of color contrasts have inspired past works involving color schemes in design.[8]

Color schemes are defined as the set of colors chosen for a design. They are often made up of two or more colors that look appealing beside one another, and that create an aesthetic feeling when used together. Color schemes depend on color harmony as they point to which colors look pleasing beside one another.[10]

A satisfactory design product is often accompanied by a successful color scheme. Over time, color design tools with the function of generating color schemes were developed to facilitate color harmonizing for designers.[11]

Use of color in visual design

- Color is used to create harmony, balance, and visual comfort in a design[10]

- Color is used to evoke the desired mood and emotion upon the viewer[5]

- Color is used to create a theme in the design[8]

- Color holds meaning and can be symbolic. In certain cultures, different colors can have different meanings.[5]

- Color is used to put emphasis on desired elements and create visual hierarchy in a piece of art[12]

- Color can create identity for a certain brand or design product[12]

- Color allows viewers to have different interpretations of visual designs. The same color can evoke different emotions, or have various meanings to different individuals and cultures[5]

- Color strategies are used for organization and consistency in a design product[9]

- In the architectural design of a retail environment, colors affect decision making which motivates consumers to buy particular products[12]

.jpg.webp)

Line

The line is an element of art defined by a point moving in space. Lines can be vertical, horizontal, diagonal, or curved. They can be any width or texture, and can be continuous, implied, or broken. On top of that, there are different types of lines aside from the ones previously mentioned. For example, you could have a line that is horizontal and zigzagged or a line that is vertical and zigzagged. Different lines create different moods, it all depends on what mood you are using line to create.

Point

A point is basically the beginning of “something” in “nothing”. It forces the mind to think upon its position and gives something to build upon in both imagination and space. Some abstract points in a group can provoke human imagination to link it with familiar shapes or forms.

Shape

A shape is defined as a two dimensional area that stands out from the space next to or around it due to a defined or implied boundary, or because of differences of value, color, or texture.[13] Shapes are recognizable objects and forms[5] and are usually composed of other elements of design.[14]

For example, a square that is drawn on a piece of paper is considered a shape. It is created with a series of lines which serve as a boundary that shapes the square and separates it from the space around it that is not part of the square.[5]

Types of shapes

Geometric shapes or mechanical shapes are shapes that can be drawn using a ruler or compass, such as squares, circles, triangles, ellipses, parallelograms, stars, and so on.[5] Mechanical shapes, whether simple or complex, produce a feeling of control and order.[14]

Organic shapes are irregular shapes[5] that are often complex and resemble shapes that are found in nature.[14] Organic shapes can be drawn by hand, which is why they are sometimes subjective and only exist in the imagination of the artist.[5]

Curvilinear shapes are composed of curved lines and smooth edges. They give off a more natural feeling to the shape. In contrast, rectilinear shapes are composed of sharp edges and right angles, and give off a sense of order in the composition. They look more human-made, structured, and artificial. Artists can choose to create a composition that revolves mainly around one of these styles of shape, or they can choose to combine both.[5]

Texture

Texture refers to the physical and visual qualities of a surface.

Uses of texture in design

- Texture can be used to attract or repel interest to an element, depending on how pleasant the texture is perceived to be.[14]

- Texture can also be used to add complex detail into the composition of a design.[5]

- In theatrical design, the surface qualities of a costume sculpt the look and feel of a character, which influences the way the audience reacts to the character.[5]

- Types of texture

Tactile texture, also known as "actual texture", refers to the physical three-dimensional texture of an object. Tactile texture can be perceived by the sense of touch. A person can feel the tactile texture of a sculpture by running their hand over its surface and feelings its ridges and dents.[5]

- Painters use impasto to build peaks and create texture in their painting.[14]

- Texture can be created through collage. This is when artists assemble three dimensional objects and apply them onto a two-dimensional surface, like a piece of paper or canvas, to create one final composition.[5]

- Papier collé is another collaging technique in which artists glue paper to a surface to create different textures on its surface.[5]

- Assemblage is a technique that consists of assembling various three-dimensional objects into a sculpture, which can also reveal textures to the viewer.[5]

Visual texture, also referred to as "implied texture", is not detectable by our sense of touch, but by our sense of sight. Visual texture is the illusion of a real texture on a two-dimensional surface.[5] Any texture perceived in an image or photograph is a visual texture. A photograph of rough tree bark is considered a visual texture. It creates the impression of a real texture on a two-dimensional surface which would remain smooth to the touch no matter how rough the represented texture is.[14]

In painting, different paints are used to achieve different types of textures. Paints such as oil, acrylic, and encaustic are thicker and more opaque and are used to create three-dimensional impressions on the surface. Other paints, such as watercolor, tend to be used for visual textures, because they are thinner and have transparency, and do not leave much tactile texture on the surface.[5]

Pattern

Many textures appear to repeat the same motif.[5] When a motif is repeated over and over again in a surface, it results in a pattern.[14] Patterns are frequently used in fashion design or textile design, where motifs are repeated to create decorative patterns on fabric or other textile materials. Patterns are also used in architectural design, where decorative structural elements such as windows, columns, or pediments, are incorporated into building design.

Space

In design, space is concerned with the area deep within the moment of designated design, the design will take place on. For a two-dimensional design, space concerns creating the illusion of a third dimension on a flat surface:[14]

- Overlap is the effect where objects appear to be on top of each other. This illusion makes the top element look closer to the observer. There is no way to determine the depth of the space, only the order of closeness.

- Shading adds gradation marks to make an object of a two-dimensional surface seem three-dimensional.

- Highlight, Transitional Light, Core of the Shadow, Reflected Light, and Cast Shadow give an object a three-dimensional look.[14]

- Linear Perspective is the concept relating to how an object seems smaller the farther away it gets.

- Atmospheric Perspective is based on how air acts as a filter to change the appearance of distant objects.

Form

In visual design, form is described as the way an artist arranges elements in the entirety of a composition.[5] It may also be described as any three-dimensional object. Form can be measured, from top to bottom (height), side to side (width), and from back to front (depth). Form is also defined by light and dark. It can be defined by the presence of shadows on surfaces or faces of an object. There are two types of form, geometric (artificial) and natural (organic form). Form may be created by the combining of two or more shapes. It may be enhanced by tone, texture or color. It can be illustrated or constructed.

Principles of the design of the art

Principles applied to the elements of design that bring them together into one design. How one applies these principles determines how successful a design may be.[1]

Unity/harmony

According to Alex White, author of The Elements of Graphic Design, to achieve visual unity is a main goal of graphic design. When all elements are in agreement, a design is considered unified. No individual part is viewed as more important than the whole design. A good balance between unity and variety must be established to avoid a chaotic or a lifeless design.[9]

Methods

- Perspective: sense of distance between elements.

- Similarity: ability to seem repeatable with other elements.

- Continuation: the sense of having a line or pattern extend.

- Repetition: elements being copied or mimicked numerous times.

- Rhythm: is achieved when recurring position, size, color, and use of a graphic element has a focal point interruption.

- Altering the basic theme achieves unity and helps keep interest.

Balance

It is a state of equalized tension and equilibrium, which may not always be calm.[9]

Types of balance in visual design

- Symmetry

- Asymmetrical balance produces an informal balance that is attention attracting and dynamic.

- Radial balance is arranged around a central element. The elements placed in a radial balance seem to 'radiate' out from a central point in a circular fashion.

- Overall is a mosaic form of balance which normally arises from too many elements being put on a page. Due to the lack of hierarchy and contrast, this form of balance can look noisy but sometimes quiet.

Hierarchy/Dominance/Emphasis

A good design contains elements that lead the reader through each element in order of its significance. The type and images should be expressed starting from most important to the least important. Dominance is created by contrasting size, positioning, color, style, or shape. The focal point should dominate the design with scale and contrast without sacrificing the unity of the whole.[9]

Scale/proportion

Using the relative size of elements against each other can attract attention to a focal point. When elements are designed larger than life, the scale is being used to show drama.[9]

Similarity and contrast

Planning a consistent and similar design is an important aspect of a designer's work to make their focal point visible. Too much similarity is boring but without similarity important elements will not exist and an image without contrast is uneventful so the key is to find the balance between similarity and contrast.[9]

Similar environment

There are several ways to develop a similar environment:[9]

- Build a unique internal organization structure.

- Manipulate shapes of images and text to correlate together.

- Express continuity from page to page in publications. Items to watch include headers, themes, borders, and spaces.

- Develop a style manual and adhere to it.

Contrasts

- Space

- Filled / Empty

- Near / Far

- 2-D / 3-D

- Position

- Left / Right

- Isolated / Grouped

- Centered / Off-Center

- Top / Bottom

- Form

- Simple / Complex

- Beauty / Ugly

- Whole / Broken

- Direction

- Stability / Movement

- Structure

- Organized / Chaotic

- Mechanical / Hand-Drawn

- Size

- Large / Small

- Deep / Shallow

- Fat / Thin

- Color

- Grey scale / Color

- Black & White / Color

- Light / Dark

- Texture

- Fine / Coarse

- Smooth / Rough

- Sharp / Dull

- Density

- Transparent / Opaque

- Thick / Thin

- Liquid / Solid

- Gravity

- Light / Heavy

- Stable / Unstable

Movement is the path the viewer’s eye takes through the artwork, often to focal areas. Such movement can be directed along lines edges, shape and color within the artwork, and more.

See also

Notes

- Lovett, John. "Design and Colour". Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- Charlotte Jirousek. Art, Design, and Visual Thinking. An online, interactive textbook. Cornell.edu, 1995.

- Martin, Jon Henry. An evaluation of Maitland Graves' principle of aesthetic order. Masters thesis, Concordia University, 1972.

- Graves, Maitland, E. The art of color and design. 2d ed. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1951.

- E., Malloy, Kaoime (2014-09-26). The art of theatrical design : elements of visual composition, methods, and practice. New York. ISBN 9781138021501. OCLC 882620042.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "basic color theory". color matters. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Jasper, Adam (2014-05-04). "Colour Theory". Architectural Theory Review. 19 (2): 119–123. doi:10.1080/13264826.2014.991017. ISSN 1326-4826. S2CID 218640469.

- Visual Color Design, 16th International Conference Information on Visualisation (IV 2012) : Montpellier, France, 11-13 July 2012 (PDF). IEEE Computer Society. Los Alamitos, Calif.: IEEE Computer Society. 2012. ISBN 9781467322607. OCLC 823906734.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - White, Alex (2011). The Elements of Graphic Design. New York, NY: Allworth Press. pp. 81–105. ISBN 978-1-58115-762-8.

- "The Architectural Colour Design Process: An Evaluation of Sequential Media via Semantic Ratings". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- Luo, Ming Ronnier (2006-06-01). "Applying colour science in colour design". Optics & Laser Technology. 38 (4–6): 392–398. Bibcode:2006OptLT..38..392L. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2005.06.025. ISSN 0030-3992.

- Tantanatewin, Warakul; Inkarojrit, Vorapat (2016-06-01). "Effects of color and lighting on retail impression and identity". Journal of Environmental Psychology. 46: 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.015. ISSN 0272-4944.

- Cindy Kovalik, Ph.D. and Peggy King, M.Ed. "Visual Literacy". Retrieved 2010-03-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Saw, James. "Design Notes". Palomar College. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

References

- Kilmer, R., & Kilmer, W. O. (1992). Designing Interiors. Orland, FL: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. ISBN 978-0-03-032233-4.

- Nielson, K. J., & Taylor, D. A. (2002). Interiors: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-296520-9

- Pile, J.F. (1995; fourth edition, 2007). Interior Design. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-13-232103-7

- Sully, Anthony (2012). Interior Design: Theory and Process. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4081-5202-7.

External links

- Art, Design, and Visual Thinking. An online, interactive textbook by Charlotte Jirousek at Cornell University.

- The 6 Principles of Design