Glass art

Glass art refers to individual works of art that are substantially or wholly made of glass. It ranges in size from monumental works and installation pieces to wall hangings and windows, to works of art made in studios and factories, including glass jewelry and tableware.

a.jpg.webp)

As a decorative and functional medium, glass was extensively developed in Egypt and Assyria. Glassblowing was perhaps invented in the 1st century BC, and featured heavily in Roman glass, which was highly developed with forms such as the cage cup for a luxury market. Islamic glass was the most sophisticated of the early Middle Ages. Then the builders of the great Norman and Gothic cathedrals of Europe took the art of glass to new heights with the use of stained glass windows as a major architectural and decorative element. Glass from Murano, in the Venetian Lagoon, (also known as Venetian glass) is the result of hundreds of years of refinement and invention. Murano is still held as the birthplace of modern glass art.

Apart from shaping the hot glass, the three main traditional decorative techniques used on formed pieces in recent centuries are enamelled glass, engraved glass and cut glass. The first two are very ancient, but the third an English invention, around 1730. From the late 19th century a number of other techniques have been added.

The turn of the 19th century was the height of the old art glass movement while the factory glass blowers were being replaced by mechanical bottle blowing and continuous window glass. Great ateliers like Tiffany, Lalique, Daum, Gallé, the Corning schools in upper New York state, and Steuben Glass Works took glass art to new levels.

Glass vessels

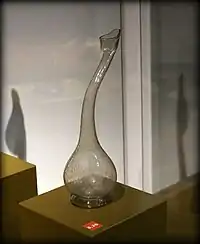

Some of the earliest and most practical works of glass art were glass vessels. Goblets and pitchers were popular as glassblowing developed as an art form. Many early methods of etching, painting, and forming glass were honed on these vessels. For instance, the millefiori technique dates back at least to Rome. More recently, lead glass or crystal glass were used to make vessels that rang like a bell when struck.

In the 20th century, mass-produced glass work including artistic glass vessels was sometimes known as factory glass.

Glass architecture

Stained glass windows

Starting in the Middle Ages, glass became more widely produced and used for windows in buildings. Stained glass became common for windows in cathedrals and grand civic buildings.

Glass facades and structural glass

The invention of plate glass and the Bessemer process allowed for glass to be used in larger segments, to support more structural loads, and to be produced at larger scales. A striking example of this was the Crystal Palace in 1851, one of the first buildings to use glass as a primary structural material.

In the 20th century, glass became used for tables and shelves, for internal walls, and even for floors.

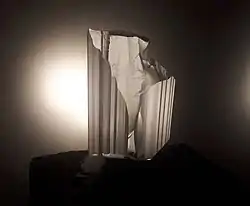

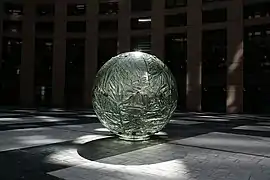

Glass sculptures

Some of the best known glass sculptures are statuesque or monumental works created by artists Livio Seguso, Karen LaMonte, and Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. Another example is René Roubícek's "Object" 1960, a blown and hot-worked piece of 52.2 cm (20.6 in)[1] shown at the "Design in an Age of Adversity" exhibition at the Corning Museum of Glass in 2005.[2] A chiselled and bonded plate glass tower by Henry Richardson serves as the memorial to the Connecticut victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.[3] In 2021, the artist Guillaume Bottazzi created a three-metre high glass sculpture on the “Domaine des Diamants Blancs”, in the extension of the Mallet-Stevens garden which adjoins the Villa Cavrois.[4]

Examples of 21st century glass sculpture:

Glass sculpture by Guillaume Bottazzi

Glass sculpture by Guillaume Bottazzi Reflections on Unity, chiseled glass orb sculpture by Henry Richardson, Asheville Art Museum.

Reflections on Unity, chiseled glass orb sculpture by Henry Richardson, Asheville Art Museum. Vestige, monumental cast glass sculpture by Karen LaMonte.

Vestige, monumental cast glass sculpture by Karen LaMonte. Glass sculpture by Livio Seguso in the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Glass sculpture by Livio Seguso in the Milwaukee Art Museum. Horizont, sculpture in glass by Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová

Horizont, sculpture in glass by Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová

Art glass and the studio glass movement

In the early 20th century, most glass production happened in factories. Even individual glassblowers making their own personalized designs would do their work in those large shared buildings. The idea of "art glass", small decorative works made of art, often with designs or objects inside, flourished. Pieces produced in small production runs, such as the lampwork figures of Stanislav Brychta, are generally called art glass. By the 1970s, there were good designs for smaller furnaces, and in the United States, this gave rise to the "studio glass" movement of glassblowers who blew their glass outside of factories, often in their own studios. This coincided with a move towards smaller production runs of particular styles. This movement spread to other parts of the world as well.

Examples of 20th-century studio glass:

Vortex Vase

Vortex Vase Wind Song Glass

Wind Song Glass Merletto canework

Merletto canework Murrine Foglio

Murrine Foglio Murrine detail

Murrine detail Picking up murrine

Picking up murrine Jack-in-the-pulpit vase

Jack-in-the-pulpit vase

Glass panels

Combining many of the above techniques, but focusing on art represented in the glass rather than its shape, glass panels or walls can reach tremendous sizes. These may be installed as walls or on top of walls, or hung from a ceiling. Large panels can be found as part of outdoor installation pieces or for interior use. Dedicated lighting is often part of the artwork.

Techniques used include stained glass, carving (wheel carving, engraving, or acid etching), frosting, enameling, and gilding (including Angel gilding). An artist may combine techniques through masking or silkscreening. Glass panels or walls may also be complemented by running water or dynamic lights.

Glass paperweights

The earliest glass art paperweights were produced as utilitarian objects in the mid 1800s in Europe. Modern artists have elevated the craft to fine art. Glass art paperweights, can incorporate several glass techniques but the most common techniques found are millefiori and lampwork—both techniques that had been around long before the advent of paperweights. In paperweights, the millefiori or sculptural lampwork elements are encapsulated in clear solid crystal creating a completely solid sculptural form.

In the mid 20th century there was a resurgence of interest in paperweight making and several artist sought to relearn the craft. In the US, Charles Kaziun started in 1940 to produce buttons, paperweights, inkwells and other bottles, using lampwork of elegant simplicity. In Scotland, the pioneering work of Paul Ysart from the 1930s onward preceded a new generation of artists such as William Manson, Peter McDougall, Peter Holmes and John Deacons. A further impetus to reviving interest in paperweights was the publication of Evangiline Bergstrom's book, Old Glass Paperweights, the first of a new genre.

A number of small studios appeared in the middle 20th century, particularly in the US. These may have several to some dozens of workers with various levels of skill cooperating to produce their own distinctive "line". Notable examples are Lundberg Studios, Orient and Flume, Correia Art Glass, St.Clair, Lotton, and Parabelle Glass.[5]

Starting in the late 1960s and early 70s, artists such as Francis Whittemore,[6] Paul Stankard,[7] his former assistant Jim D'Onofrio,[8] Chris Buzzini,[9] Delmo[10] and daughter Debbie Tarsitano,[11] Victor Trabucco[12] and sons, Gordon Smith,[13] Rick Ayotte[14] and his daughter Melissa, the father and son team of Bob and Ray Banford,[15] and Ken Rosenfeld[16] began breaking new ground and were able to produce fine paperweights rivaling anything produced in the classic period.

Glass fashion

Jewelry

The first uses of glass were in beads and other small pieces of jewelry and decoration. Beads and jewelry are still among the most common uses of glass in art and can be worked without a furnace.

It later became fashionable to wear functional jewelry with glass elements, such as pocket watches and monocles.

Wearables and couture

Starting in the late 20th century, glass couture refers to the creation of exclusive custom-fitted clothing made from sculpted glass. These are made to order for the body of the wearer. They are partly or entirely made of glass with extreme attention to fit and flexibility. The result is usually delicate, and not intended for regular use.

Techniques and processes

Several of the most common techniques for producing glass art include: blowing, kiln-casting, fusing, slumping, pâté-de-verre, flame-working, hot-sculpting and cold-working. Cold work includes traditional stained glass work as well as other methods of shaping glass at room temperature. Cut glass is worked with a diamond saw, or copper wheels embedded with abrasives and polished to give gleaming facets; the technique used in creating Waterford crystal.[17]

Fine paperweights were originally made by skilled workers in the glass factories in Europe and the United States during the classic period (1845-1870.) Since the late 1930s, a small number of very skilled artists have used this art form to express themselves, using mostly the classic techniques of millefiori and lampwork.[18]

Art is sometimes etched into glass via the use of acid, caustic, or abrasive substances. Traditionally this was done after the glass was blown or cast. In the 1920s a new mould-etch process was invented, in which art was etched directly into the mould so that each cast piece emerged from the mould with the image already on the surface of the glass. This reduced manufacturing costs and, combined with a wider use of colored glass, led to cheap glassware in the 1930s, which later became known as Depression glass.[19] As the types of acids used in this process are extremely hazardous, abrasive methods gained popularity.

Knitted glass

Knitted glass is a technique developed in 2006 by artist Carol Milne, incorporating knitting, lost-wax casting, mold-making, and kiln-casting. It produces works that look knitted, though they are made entirely of glass.

Glass printing

In 2015, the Mediated Matter group and Glass Lab at MIT produced a prototype 3D printer that could print with glass, through their G3DP project. This printer allowed creators to vary optical properties and thickness of their pieces. The first works that they printed were a series of artistic vessels, which were included in the Cooper Hewitt's Beauty exhibit in 2016.

Glass printing is theoretically possible at large and small physical scales and has the capacity for mass production. However, as of 2016 production still requires hand-tuning, and has mainly been used for one-off sculptures.

Pattern making

Methods to make patterns on glass include caneworking such as murrine, engraving, enameling, millefiori, flamework, and gilding.

Methods used to combine glass elements and work glass into final forms include lampworking.

Museums

Historical collections of glass art can be found in general museums. Modern works of glass art can be seen in dedicated glass museums and museums of contemporary art. These include the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, and Corning Museum of Glass, in Corning, NY, which houses the world's largest collection of glass art and history, with more than 45,000 objects in its collection.[20] The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston features a 42.5 feet (13.0 m) tall glass sculpture, Lime Green Icicle Tower, by Dale Chihuly.[21] In February 2000 the Smith Museum of Stained Glass Windows, located in Chicago's Navy Pier, opened as the first museum in America dedicated solely to stained glass windows. The museum features works by Louis Comfort Tiffany and John Lafarge, and is open daily free to the public.[22] The UK's National Glass Centre is located in the city of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear.

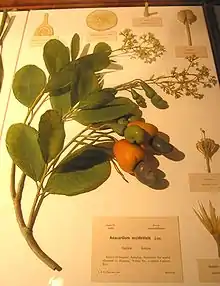

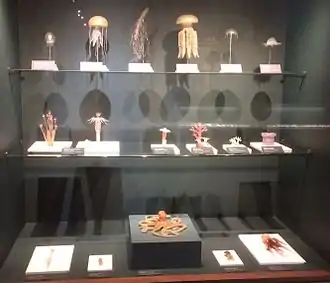

Blaschka models

Among the finest - and arguably the most detailed - examples of glass art are the Glass sea creatures and their younger botanical cousins the Glass Flowers, scientifically accurate models of marine invertebrates and various plant specimens crafted by famed Bohemian lampworkers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka from 1863 to 1936. The Glass Flowers are a unique collection made for and located only at Harvard Museum of Natural History, while the glass invertebrates are located in collections the world over. Given the unmatched anatomical flawlessness of both, many believe that the Blaschkas had a secret method of lampworking which they never revealed. This, however, is not true, as Leopold himself noted in an 1889 letter to Mary Lee Ware (the patron sponsor of the Glass Flowers):

Many people think that we have some secret apparatus by which we can squeeze glass suddenly into these forms, but it is not so. We have the touch.[23] My son Rudolf has more than I have, because he is my son, and the touch increases in every generation. The only way to become a glass modeler of skill, I have often said to people, is to get a good great-grandfather who loved glass; then he is to have a son with like tastes; he is to be your grandfather. He in turn will have a son who must, as your father, be passionately fond of glass. You, as his son, can then try your hand, and it is your own fault if you do not succeed. But, if you do not have such ancestors, it is not your fault. My grandfather was the most widely known glassworker in Bohemia.[24][25]

Over the course of their collected lives Leopold and Rudolf crafted as many as ten thousand glass marine invertebrate models plus the 4,400 botanical ones that are Glass Flowers.[26][27] The rumor of secret methods is partly owed to the fact that the family touch, as Leopold described it, died with the childless Rudolf, meaning Blaschka glass art ceased being produced in the mid-20th century. Regardless, their work remains an inspiration to glassblowers today, with the Glass Flowers being among the most popular exhibits at Harvard while invertebrate models are being remembered and rediscovered everywhere.[28][29]

See also

References

- "René Roubícek". The Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "Czech Glass: Design in an Age of Adversity 1945-1980". The Corning Museum of Glass. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Pelland, Dave. "9/11 Memorial, Danbury". CTMonuments.net. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Guillaume Bottazzi: Dreamlike Spaces". 31 May 2021.

- Flemming, M., p 38-42

- Dunlop, Paul H. p354

- Dunlop, Paul H. p315-317

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 123

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 267

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 328

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 326

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 335

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 304

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 267

- Dunlop, Paul H. p 44 & 45

- Dunlop, Paul H., p275

- "Waterford Crystal Visitors Centre". Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Dunlop, Paul H. (2009). The Dictionary of Glass Paperweights. United States: Papier Presse. ISBN 978-0-9619547-5-8.

- "Depression Glass". Archived from the original on 2014-12-02. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- "Corning Museum of Glass". Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- "Lime Green Icicle Tower". Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- Smith Museum of Stained Glass Windows Archived 2013-01-04 at archive.today

- The German word used here is takt, usually translated as "tact" in English. The German word has several different meanings, and in some cases is translated as "subtlety" or "heartbeat". In this context "the touch" or "the feeling" is closer to the intended meaning than the usual "tact". https://m.interglot.com/de/en/Takt

- Schultes, Richard Evans; Davis, William A.; Burger, Hillel (1982). The Glass Flowers at Harvard. New York: Dutton. Excerpt available at: "The Fragile Beauty of Harvard's Glass Flowers". The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles. February 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- Richard, Frances (Spring 2002). "Great Vitreous Tract". Cabinet Magazine.

- "Back to Back Bay After an Absence of Ten Years". The New York Times. June 10, 1951. p. XX17.

- Geoffrey N. Swinney & (2008) Enchanted invertebrates: Blaschka models and other simulacra in National Museums Scotland, Historical Biology, 20:1, 39-50, DOI: 10.1080/08912960701677036 - https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912960701677036

- The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants. The Harvard Museum of Natural History

- "The Delicate Glass Sea Creatures of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka". September 2016.