Scafell Pike

Scafell Pike (/ˈskɔːfɛl paɪk/)[2] is the highest and the most prominent mountain in England, at an elevation of 978 metres (3,209 ft) above sea level.[1][3] It is located in the Lake District National Park, in Cumbria, and is part of the Southern Fells and the Scafell massif.[4]

| Scafell Pike | |

|---|---|

Scafell Pike (centre) from Yewbarrow | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 978 m (3,209 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 912 m (2,992 ft) Ranked 13th in British Isles |

| Parent peak | Snowdon |

| Isolation | 151.98 km (94.44 mi) |

| Listing | Marilyn, Hewitt, Hardy, Wainwright, County Top, Nuttall, Country high point |

| Coordinates | 54°27′15″N 3°12′41″W |

| Geography | |

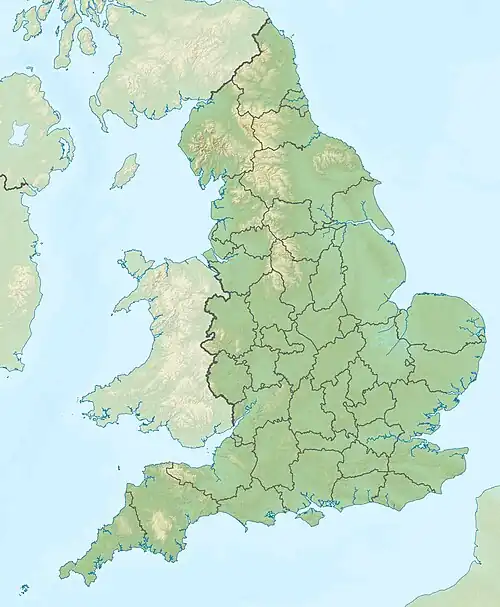

Scafell Pike Location in the Lake District  Scafell Pike Location in Copeland Borough  Scafell Pike #Location in England | |

| Location | Lake District National Park, Cumbria, England |

| Parent range | Lake District, Southern Fells |

| OS grid | NY215072 |

| Topo map | OS Landrangers 89, 90, Explorer OL6 |

Scafell Pike forms part of the inactive Scafells volcano.[5]

Etymology and name history

The name Scafell is believed by some to derive from the Old Norse skalli fjall, meaning either the fell with the shieling or the fell with the bald summit, and is first recorded in 1578 in the corrupted form Skallfield.[6] An alternative derivation is from the Old Norse "skagi", meaning a cape, headland, promontory or peninsula – so giving an etymology that aligns with Skaw in Shetland.[7] It originally referred to Scafell, which neighbours Scafell Pike.[8] What are now known as Scafell Pike, Ill Crag, and Broad Crag were collectively called either the Pikes (peaks) or the Pikes of Scawfell (see below regarding spelling); from many angles Scafell seems to be the highest peak, and the others were thus considered subsidiary to it. The name Scawfell Pikes was adopted "by common consent" according to Jonathan Otley, shortly before the publication of the 4th edition of his guidebook in 1830.[9] Up to this point, England's highest mountain (its status as such was not known until the early 1800s) did not have a name of its own; it was labelled Sca-Fell Higher Top by the Ordnance Survey in their initial work in Cumbria in the first decade of the 19th century.[10] The newly developed name reported by Otley first appeared on a published Ordnance Survey map in 1865.

Formerly the name was spelled Scawfell, which better reflects local pronunciation.[8][11][12][note 1] This spelling has declined due to the Ordnance Survey's use of Scafell on their 1865 map and thereafter.

Topography

Scafell Pike is one of a horseshoe of high fells, open to the south, surrounding the head of Eskdale, Cumbria. It stands on the western side of the cirque, with Scafell to the south and Great End to the north. This ridge forms the watershed between Eskdale and Wasdale, which lies to the west.[13]

The narrowest definition of Scafell Pike begins at the col of Mickledore 831.6 m (2,728 ft) in the south, takes in the wide, stony summit area and ends at the next depression, Broad Crag Col, c. 877.6 m (2,879 ft). A more inclusive view takes in two further tops: Broad Crag, 935.3 m (3,069 ft) and Ill Crag, 930.9 m (3,054 ft), the two being separated by Ill Crag Col, 882.3 m (2,895 ft). This is the position taken by most guidebooks.[14][13] North of Ill Crag is the more definite depression of Calf Cove at 853.4 m (2,800 ft), before the ridge climbs again to Great End, 909.5 m (2,984 ft).

Scafell Pike also has outliers on either side of the ridge. Lingmell 807 m (2,648 ft), to the north west, is invariably regarded as a separate fell,[14][13] while Pen, 760 metres (2,490 ft), a shapely summit above the Esk, is normally taken as a satellite of the Pike. Middleboot Knotts is a further top lying on the Wasdale slopes of Broad Crag, which is listed as a Nuttall.

The rough summit plateau is fringed by crags on all sides with Pikes Crag and Dropping Crag above Wasdale and Rough Crag to the east. Below Rough Crag and Pen is a further tier, named Dow Crag and Central Pillar on Ordnance Survey maps, although known as Esk Buttress among climbers.[15]

Broad Crag Col is the source of Little Narrowcove Beck in the east and of Piers Gill in the west. The latter works its way around Lingmell to Wast Water through a spectacular ravine, one of the most impressive in the Lake District. It is treacherous in winter, as when it freezes over it creates an icy patch, with lethal exposure should you slip. Broad Crag is a small top with its principal face on the west and the smaller Green Crag looking down on Little Narrowcove. From Broad Crag, the ridge turns briefly east across Ill Crag Col and onto the shapely pyramidal summit of Ill Crag. Ill Crag and its associated crags overlook Eskdale.[13]

Scafell Pike has a claim to the highest standing water body in England in Broad Crag Tarn, which (confusingly) is on Scafell Pike proper, rather than on Broad Crag. It lies at about 820 m (2,690 ft), a quarter of a mile (400 m) south of the summit. Foxes Tarn on Scafell is of comparable height.[16]

Mountain classification

Scafell Pike is a Marilyn summit which automatically makes it a HuMP and a TuMP. Scafell Pike is topologically unusual because the Marilyn qualification contour line (150 metres below the summit) passes around Scafell which is itself a HuMP.

Scafell Pike's Maquaco Line also encloses three other TuMP summits, Broad Crag, Ill Crag and Great End.

Summit

The summit was donated to the National Trust in 1919 by Lord Leconfield "in perpetual memory of the men of the Lake District who fell for God and King, for freedom peace and right in the Great War 1914–1918 ...".[17] There is a better-known war memorial on Great Gable, commemorating the members of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club.[18][19]

The actual height of Scafell Pike is a matter of definition or guesswork. The highest point is buried beneath a massive summit cairn over 3 metres high and it is not known how high the fabric of the mountain rises under the cairn. Traditionally the height was given as a very memorable 3,210 feet (978.4 m).[13] The rounded metric height of 978 metres converts to 3209 feet ±1 ft 8 in.

Scafell Pike is one of three British peaks climbed as part of the National Three Peaks Challenge, and is the highest ground for over 90 miles (145 km).

| Name | Grid ref | Height | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ill Crag | NY223073 | 930.9 m (3,054 ft) | Hewitt, Nuttall |

| Broad Crag | NY218075 | 935.4 m (3,069 ft) | Hewitt, Nuttall |

| Middleboot Knotts | NY213080 | 702.9 m (2,306 ft) | Nuttall |

Geology

Ordovician and volcanic activity

Scafell Pike consists of igneous rock, including breccia, andesite and rhyolite, as well as geothermal tufa,[20] dating from the Ordovician; it is geologically part of the Borrowdale Volcanics and along with the other peaks of the Scafells, forms part of an extinct volcano which was active around 400-450 million years ago.[5]

Pleistocene glacial activity

The rugged summit of Scafell Pike was shaped by glacial erosion of the Last Glacial Maximum (~20,000 YA), during which the Lake District was overlain by ice sheets with thicknesses of several kilometers.[21]

Contemporary weathering

The summit plateau of Scafell Pike, and that of other neighbouring peaks, is covered with shattered rock debris which provides the highest-altitude example of a summit boulder field in England.[22] The boulder field is thought to have been caused in part by weathering, such as frost action. Additional factors are also considered to be important; however, opinion varies as to what these may be. James Clifton Ward suggested that weathering with earthquakes as a secondary agent could be responsible, while John Edward Marr and Reginald Aldworth Daly believed that earthquakes were unnecessary and suggested that frost action with other unspecified agents was more likely.[23] To the north of the summit are a number of high altitude gills which flow into Lingmell Beck. These are good examples in Cumbria for this type of gill and are also biologically important due to their species richness.[22]

Tourism

Scafell Pike is a popular destination for walkers. There is open access to Scafell and the surrounding fells, with many walking and rock climbing routes. Paths connect the summit with Lingmell Col to the northwest, Mickledore to the southwest, and Esk Hause to the northeast, and these in turn connect with numerous other paths, giving access to walkers from many directions including Wasdale Head to the west, Seathwaite to the north, Langdale to the east, and Eskdale to the southwest. The shortest route is from Wasdale Head, about 80 metres above sea level, where there is a climbers' hotel, the Wasdale Head Inn, made popular in the Victorian period by Owen Glynne Jones and others. According to the National Trust, as of 2014 there were over 100,000 people per year climbing Scafell Pike from Wasdale Head,[24] many as part of the National Three Peaks Challenge.

Survey point

Scafell Pike was used in 1826 as a station in the Principal Triangulation of Britain by the Ordnance Survey when they fixed the relative positions of Britain and Ireland. Angles between Slieve Donard in Northern Ireland and Scafell Pike were taken from Snowdon in Wales as were angles between Snowdon and Scafell Pike from Slieve Donard. Given the need for clear weather to achieve these very long-range observations (111 miles (179 km) to Slieve Donard), the Ordnance surveyors spent much of the summer camped on the respective mountain tops. Scafell Pike was not used as a station in the earlier part of the Principal Triangulation of Britain, even though Sca-Fell formed one corner of a Principal Triangle.[note 2] The Ordnance Survey's high precision theodolite was not taken to the summit until 1841.[10][25][26]

Views from the summit

Summer

(Scroll left or right)

Winter

List of summits visible

As the highest ground in England, Scafell Pike has a very extensive view, ranging from the Mourne Mountains in Northern Ireland to Snowdonia in Wales. On a clear day, the following prominent mountain tops (Marilyns) can be seen the summit.[27]

- Dun Rig, 77 miles (124 km), 2 degrees

- Binsey, 18 miles (29 km), 2 degrees

- Turner Cleuch Law, 71 miles (114 km), 4 degrees

- Dale Head, 5 miles (8.0 km), 5 degrees

- Wisp Hill, 58 miles (93 km), 11 degrees

- Skiddaw, 14 miles (23 km), 12 degrees

- Roan Fell, 55 miles (89 km), 15 degrees

- Knott, 17 miles (27 km), 17 degrees

- Peel Fell, 63 miles (101 km), 24 degrees

- Blencathra, 14 miles (23 km), 28 degrees

- The Cheviot, 83 miles (134 km), 31 degrees

- Cold Fell, 39 miles (63 km), 39 degrees

- Howgill Fells, 29 miles (47 km), 103 degrees

- Bow Fell, 2 miles (3 km), 105 degrees

- Yorkshire Three Peaks, 36, 44 and 38 miles (58, 71 and 61 km), 119 degrees

- Boulsworth Hill, 63 miles (101 km), 135 degrees

- Pendle Hill, 55 miles (89 km), 138 degrees

- Ward's Stone, 38 miles (61 km), 142 degrees

- The Old Man of Coniston, 7 miles (11 km), 149 degrees

- Winter Hill, 64 miles (103 km), 154 degrees

- Snaefell, 52 miles (84 km), 257 degrees

- Slieve Donard, 111 miles (179 km), 262 degrees

- Slieve Croob, 112 miles (180 km), 268 degrees

- Beneraird, 80 miles (130 km), 303 degrees

- Merrick, 69 miles (111 km), 315 degrees

- Pillar, 4 miles (6 km), 318 degrees

- Cairnsmore of Carsphairn, 68 miles (109 km), 326 degrees

- High Stile, 6 miles (10 km), 328 degrees

- Criffel, 37 miles (60 km), 334 degrees

- Grasmoor, 8 miles (13 km), 342 degrees

- Great Gable, 2 miles (3.2 km), 351 degrees

See also

Notes

- These references on spelling of "Scafell"/"Scawfell" are examples of the more common usage during the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, as can readily be found in the many contemporary guidebooks and local and national newspapers. A useful contrast is the difference in Baddely's guide (1st edn. 1888 and many later editions) between the guide text ("Scafell", following the maps used in this common guide-book) and all the adverts therein of hotels, tours and views, which were placed by local businesses ("Scawfell").

- Absence of angles taken from one corner of some triangles was attributed to difficulties of access in the preface of the 1811 report by the Ordnance Survey.

References

- Bathurst, David (2012). Walking the county high points of England. Chichester: Summersdale. pp. 272–278. ISBN 978-1-84-953239-6.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6. In isolation Scafell is /ˌskɔːˈfɛl/.

- "Marilyns of England". www.peakbagger.com. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Gannon, Paul (April 2009). Rock Trails Lakeland - A Hillwalker's Guide to the Geology & Scenery. Pesda Press. ISBN 9781906095154. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- Geology of England and Wales, pp118ff

- Stuart Rae. "Fells".

- Zoëga, G T (1922). Icelandic-English Dictionary. Iceland. p. 444.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dorothy Wordsworth's ascent of Scafell Pike, 1818, http://www.pastpresented.ukart.com/eskdale/wordsworth1.htm

- Otley, Jonathan (1830). A concise description of the English lakes, and adjacent mountains: with general directions to tourists; notices of the botany, mineralogy, and geology of the district; observations on meteorolgy; the floating island in Derwent lake; and black-lead mine in Borrowdale (4th ed.). Keswick: author. p. 64. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Mudge, Lieutenant-Colonel William; Colby, Captain Thomas (1811). An Account of the Trigonometrical Survey Carried on by Order of the Master-General of His Majesty's Ordnance in the Years 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, 1807, 1808 and 1809 (PDF). Charing Cross, London: W Faden.

- Martineau, Harriet (1855). A Complete Guide to the English Lakes. Windermere: John Garnett – via Archive.org.

- Holland, CF (1924). Climbs on the Scawfell Group – A Climbers' Guide (1st ed.). Fell & Rock Climbing Club.

- Wainwright, A. (1960). The Southern Fells. London: Francis Lincoln. ISBN 0-7112-2230-4.

- Richards, Mark: Mid-Western Fells: Collins (2004): ISBN 0-00-711368-4

- British Mountain Maps: Lake District: Harvey (2006): ISBN 1-85137-467-1

- Blair, Don: Exploring Lakeland Tarns: Lakeland Manor Press (2003): ISBN 0-9543904-1-5

- Scafell Pike Summit, Cumbria – World War I Memorials and Monuments on. Waymarking.com. Retrieved on 2014-04--04-12.

- Westaway, Jonathan. (1970-01-01) Mountains of Memory, Landscapes of Loss: Scafell Pike and Great Gable as War Memorials, 1919–1924 | Jonathan Westaway. Academia.edu. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- "Mammoth mission to repair remarkable World War One memorial on Scafell Pike". Whitehaven News. 15 May 2018.

- "About Scafell". ClimbScafell. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Scoon, Roger N (8 April 2021). Geotraveller - Geology of Famous Geosites and Areas of Historical Interest. Springer. ISBN 978-3030546939.

- "Scafell Pikes SSSI citation sheet" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Hay, T (1942). "Physiographical Notes from Lakeland". The Geographical Journal. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 100, No. 4. 100 (4): 165–173. doi:10.2307/1788974. JSTOR 1788974.

- "Three Peaks Partnership (formerly the Inter Mountain Working Group)" (PDF). www.thebmc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Seymour, W. A., ed. (1980). A History of the Ordnance Survey (PDF). Folkestone, Kent: Wm Dawson & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 0-7129-0979-6.

- "Carlisle Journal". Col 8. 9 October 1841. p. 2. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Computer generated virtual panoramas North South Index

External links

- Computer generated virtual panoramas North South Index

- Scafell Pike is at coordinates 54.454435°N 3.210168°W

- Scafell Pike Sunny Photos from the West at Wasdale Head and North from Borrowdale by Keswick

- Descriptions of the Walking Routes up Scafell Pike