Hinduism in Java

Hinduism has historically been a major religious and cultural influence in Java, Indonesia. Hinduism was the dominant religion in the region before the arrival of Islam. In recent years, it has also been enjoying something of a resurgence, particularly in the eastern part of the island.[1][2]

History

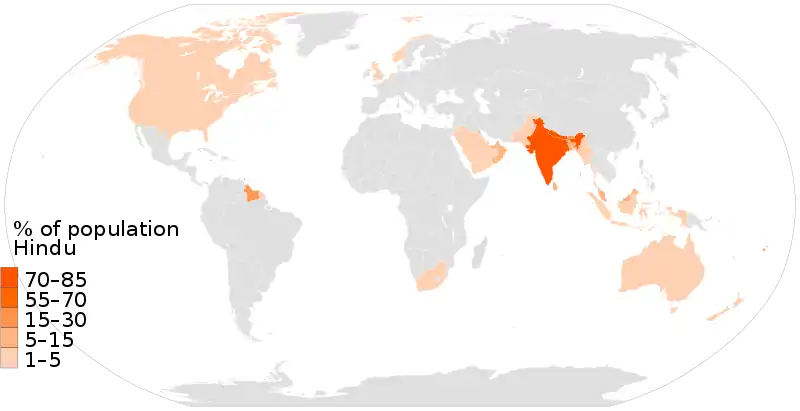

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

Both Java and Sumatra were subject to considerable cultural influence from India during the first and second millennia of the Common Era. Both Hinduism and Buddhism, which are both Indian religions and share a common historical background and whose membership may even overlap at times, were widely propagated in the Maritime Southeast Asia.

Hinduism and the Sanskrit language through which it was transmitted, became highly prestigious and the dominant religion in Java. Many Hindu temples were built, including Prambanan near Yogyakarta, which has been designated a World Heritage Site; and Hindu kingdoms flourished, of which the most important was Majapahit.

In the sixth and seventh centuries many maritime kingdoms arose in Sumatra and Java which controlled the waters in the Straits of Malacca and flourished with the increasing sea trade between China and India and beyond. During this time, scholars from India and China visited these kingdoms to translate literary and religious texts.

Majapahit was based in Central Java, from where it ruled a large part of what is now western Indonesia. The remnants of the Majapahit kingdom shifted to Bali during the sixteenth century as Muslim kingdoms in the western part of the island gained influence.[3]

Although Java was substantially converted to Islam during the 15th century and afterwards, substantial elements of Hindu (and pre-Hindu) customs and beliefs persist among ordinary Javanese. Particularly in central and eastern Java, Abangan or 'nominal' Muslims are predominant. 'Javanists', who uphold this folk tradition, coexist along with more orthodox Islamicizing elements.

Survivals

Hinduism or Hindu-animist fusion have been preserved by a number of Javanese communities, many of which claim descent from Majapahit warriors and princes. The Osings in the Banyuwangi Regency of East Java are a community whose religion shows many similarities to that of Bali. The Tenggerese communities at the foot of Mount Bromo are officially Hindu, but their religion includes many elements of Buddhism including the worship of Lord Buddha along with Hindu trinity Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma. The Badui in Banten have a religion of their own which incorporates Hindu traits. Many Javanese communities still practice Kejawèn, consisting of an amalgam of animistic, Buddhist, and Hindu aspects. Yogyakarta is stronghold of Kejawen.[4]

Modern resurgence

It is interesting to study conversion to Hinduism in two close and culturally similar regions, the Yogyakarta region, where only sporadic conversions to Hinduism had taken place, and the Klaten region, which has witnessed the highest percentage of Hindu converts in Java. It has been argued that this dissimilarity was related to the difference in the perception of Islam among the Javanese population in each region. Since the mass killings of 1965–1966 in Klaten had been far more awful than those in Yogyakarta, in Klaten the political landscape had been far more politicized than in Yogyakarta. Because the killers in Klaten were to a large extent identified with Islam, the people in this region did not convert to Islam, but preferred Hinduism (and Christianity).[5] Also there is fear for those who are adherent of Javanism of the purge, in order to hide their practices they converted into Hinduism, though they may not entirely practice the religion. Many of the new "Hindus" in Gunung Lawu and Kediri are example of this.[6]

The existence of Hindu temples in an area sometimes encourages local people to reaffiliate with Hinduism, whether these are archaeological temple sites (candi) being reclaimed as places of Hindu worship, or recently built temples (pura). The great temple at Prambanan, for example, is also in the Klaten area. An important new Hindu temple in eastern Java is Pura Mandaragiri Sumeru Agung, located on the slope of Mt Semeru, Java's highest mountain. Mass conversions have also occurred in the region around Pura Agung Blambangan, another new temple, built on a site with minor archaeological remnants attributed to the kingdom of Blambangan, the last Hindu polity on Java, and Pura Loka Moksa Jayabaya (in the village of Menang near Kediri), where the Hindu king and prophet Jayabaya is said to have achieved spiritual liberation (moksa). Another site is the new Pura Pucak Raung in East Java, which is mentioned in Balinese literature as the place from where Maharishi Markandeya took Hinduism to Bali in the fifth century AD.

An example of resurgence around major archaeological remains of ancient Hindu temple sites was observed in Trowulan near Mojokerto, the capital of the legendary Hindu empire Majapahit. A local Hindu movement is struggling to gain control of a newly excavated temple building which they wish to see restored as a site of active Hindu worship. The temple is to be dedicated to Gajah Mada, the man attributed with transforming the small Hindu kingdom of Majapahit into an empire. Although there has been a more pronounced history of resistance to Islamization in East Java, Hindu communities are also expanding in Central Java near the ancient Hindu monuments of Prambanan.

See also

References

- "Great Expectations: Hindu Revival Movements in Java". Archived from the original on 2021-10-25.

- Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase publishing. 2006. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- James Fox, Indonesian Heritage: Religion and ritual, Volume 9 of Indonesian heritage, Editor: Timothy Auger, ISBN 978-9813018587

- Krithika Varagur (5 April 2018). "Indonesians Fight to Keep Mystical Religion of Java Alive". Voice of America. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- Verma, Rajeev (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Hinduism. Major Sects: Kalpaz Publications. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-7835-718-8.

- "Traces of Hinduism on Mount Lawu". Viva.co.id. 2010-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-19.