Gajah Mada

Gajah Mada (c. 1290 – c. 1364), also known as Jirnnodhara,[3] was a powerful military leader and mahapatih (the approximate equivalent of a modern prime minister) of the Javanese empire of Majapahit during the 14th century. He is credited in Old Javanese manuscripts, poems, and inscriptions with bringing the empire to its peak of glory.[4]

Gajah Mada ꦓꦗꦃꦩꦢ | |

|---|---|

A modern artist's impression of Gajah Mada, based on the outdated, earlier illustration by M. Yamin | |

| Mahapatih/"Mahapatih" of the Majapahit Empire | |

| In office 1331[1] – c. 1364 | |

| Monarchs | Jayanegara Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi Hayam Wuruk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1290 |

| Died | c. 1364 |

| Religion | Shiva-Buddha[2][Note 1] |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Sadeng Rebellion Ra Kuti Rebellion Bedahulu War Battle of Bubat Padompo[Note 2] |

He delivered an oath called Sumpah Palapa, in which he vowed to live an ascetic lifestyle by not consuming food containing spices until he had conquered all of the Southeast Asian archipelago of Nusantara for Majapahit.[5] During his reign, the Hindu epics, including the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata, became ingrained in the Javanese culture and worldview through the performing arts of wayang kulit (“leather puppets”).[6] He is considered an important national hero in modern Indonesia,[7] as well as a symbol of patriotism and national unity. Historical accounts of his life, political career, and administration are taken from several sources, mainly the Pararaton ("The Book of Kings"), the Nagarakretagama (a Javanese-language eulogy), and an inscription dating from the mid-14th century.

Depiction

- Brajanata statue, at the National Museum of Indonesia, No. 5136/310d

- Bima statue, No. 2776/286b

Much of the modern popular depiction of Gajah Mada derives from the imagination of Mohammad Yamin in his 1945 book Gajah Mada: Pahlawan Persatuan Nusantara. One day in the 1940s, Yamin visited Trowulan, the site of the capital city of the former Majapahit kingdom. He found fragments of terracotta, one of which was a piggy bank in the form of the face of a man with a stocky face and curly hair. Based on the look on the piggy bank's face, Yamin interpreted this as the face of Gajah Mada, the unifier of the archipelago. Yamin then asked the artist Henk Ngantung to make a painting based on the terracotta fragment. The painting was displayed as the cover of Yamin's book. Many people disagree with Yamin's opinion because it is impossible for the face of a figure as big as Gajah Mada to be displayed in a piggy bank. Such a portrayal is considered an insult because usually the state leaders during the Hindu-Buddhist era, including Majapahit, were made in effigy as statues. Some even believe that the face was none other than Yamin's own face.[8]

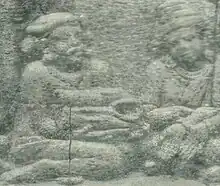

Another illustration of the historical Gajah Mada, different from Yamin's, is the result of research at the University of Indonesia by archaeologist Agus Aris Munandar. He interpreted that Gajah Mada was depicted as Bima in wayang shadow-puppet shows, with a transverse mustache.[9] In popular depiction, Gajah Mada is mostly shown bare-chested, wearing a sarong, and using a weapon in the form of a kris. While this may have been true on civilian duties, his official outfit might have been different: a Sundanese patih explained in the kidung Sundayana that Gajah Mada wore a gold-embossed karambalangan (breastplate) and was armed with a gold-layered spear and a shield full of diamond decoration.[10][11]

- A cuirass being presented by a brahmin, depicted in the Borobudur temple.

- War attire or armor depicted in a statue from a candi in Singasari

- Cuirass being held by a deity, from earlier, 10–11th century Nganjuk, East Java

According to Munandar, at first Gajah Mada was depicted as a Brajanata character from the Panji tales, and as Bima from the Mahābhārata in later eras. The Panji story was known earlier than the activities of making Bima statues, which apparently began in the mid-15th century, so the former was likely Gajah Mada's original depiction. The glorification of Gajah Mada in the first stage is profane—in the form of its depiction as Brajanata, but then the glorification of Gajah Mada occurs in the second stage which is more sacred, which is equated with Bima as an aspect of Siva.[12] In the statue found at the National Museum of Indonesia (No. 5136/310d), the statue is depicted with a sturdy body, transverse mustache, wavy curls, at the top of the head there is a hair tie with a ribbon forming like a tekes hat. He wears clothes and jewelry, bracelets and an upper armband in the form of a snake like Bima's.[13]

The traditional Bima statue depiction associated with Gajah Mada was made at the end of Majapahit in the mid-15th century. The characteristics are: a) wearing a supit urang crown (his hair is shaped in two arches at the top of the head like a shrimp tongs), b) a transverse mustache, c) strong body, d) wearing poleng (black and white) cloth, and e) the phallus is always depicted standing out.[14] In the Bima statue stored in the National Museum (No. 2776/286b), he is depicted standing upright with both hands beside his body, his right hand holding a gadha (a kind of mace); his phallus is depicted as protruding with a shawl hanging between his legs; he is wearing a serpent upavita, a crown of supit urang, a grim face, and a thick transverse mustache; and the hair above the forehead is described as curly, forming a jamang (forehead decoration).[15] The similarity between the statue of Brajanata as the embodiment of Gajah Mada and the statue of Bima is not a coincidence, but there is an underlying conception: this conception developed along with the distance between historical events and their worshippers at a later time.[14]

Meaning of name

The word "Gajah" (elephant) refers to a large animal that is respected by other animals. In Hindu mythology it is believed to be a vahana (animal mount) of the god Indra. Elephants are also associated with Ganesha, the elephant-headed god with a human body, the son of Shiva and Parvati. As for the word "Mada", in the ancient Javanese language (possibly derived from Sanskrit where the word has the same meaning), it means "drunk"; when an elephant is drunk, he will walk arbitrarily and violently, overcoming all obstacles. So when it is associated with the figure of Gajah Mada, the name can be interpreted in two ways, namely:[16]

- He considered himself to be the vehicle of the king, the executor of the king's orders, just as the elephant Airavata became the vahana of the god Indra.

- He is a person who seems drunk and violent when faced with various obstacles that will hinder the progress of the kingdom. It really is the right choice of name and it seems that the name has been carefully thought out, its meaning having been previously used for his name.[16]

In the Gajah Mada inscription, another nickname was used, namely Rakryan Mapatih Jirnnodhara. It is possible the name is just a title for Gajah Mada, but it can also be seen as the official name. The meaning of the word Jirnnodhara is "builder of something new" or "restorer of something that has fallen apart". In a literal sense, Gajah Mada is the builder of caitya for Kertanegara, which did not exist before. In a figurative sense, he can be seen as a restorer and successor to Kertanegara's ideas in the Dwipantara Mandala concept.[3]

Rise to power

Not much is known about Gajah Mada's early life, but he was born into an ordinary family. Early accounts mention his career as a commander of the Bhayangkara, an elite royal guard for the Majapahit king and royal family.

When Rakrian Kuti, an official from Majapahit, rebelled against King Jayanegara (r. 1309–1328) in 1321, Gajah Mada and the mahapatih Arya Tadah rescued the king and his family by escaping from the capital city of Trowulan. Later Gajah Mada helped the king return to the capital and crush the rebellion. Seven years later, Jayanegara was murdered by the court physician Rakrian Tanca, an aide of Rakrian Kuti.

Another version suggests that Jayanegara was assassinated by Gajah Mada in 1328. Jayanegara was overly protective of his two half-sisters, born from Kertarajasa's youngest queen, Dyah Dewi Gayatri. Complaints by the two young princesses led to the intervention of Gajah Mada. His solution was to arrange for a surgeon to murder the king while pretending to perform surgery.

Jayanegara was immediately succeeded by his half-sister Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi (r. 1328–1350). However, when she took the throne, the Sadeng and Keta region did not send their delegations, which was interpreted as a rebellion. This was later confirmed when Tribhuwana's spies discovered that both regions were preparing for rebellions. Sadeng and Keta were coastal regions who were formerly conquered by Majapahit. However, the death of Nambi in 1316 (a local patih who was deemed instrumental in raising both regions) also contributed to the rebellion. At this time Sadeng was also led by a famed Majapahit general, Wirota Wiraganti.

While Gajah Mada was still currently a patih, he was sent by Tribhuwana with the advice of the sickly mahapatih Arya Tadah, to negotiate with rebel leaders in 1331. However, the Majapahit general Ra Kembar, a rival of Gajah Mada, preceded his arrival with his army to crush both rebellions. His men Jabung Tarewes, Lembu Peteng, dan Ikal-Ikalan Bang were also the ones implicated in the murder of Nambi.[17]

This led to a conflict between Gajah Mada's and Ra Kembar's forces which was only resolved when Tribhuwana herself led the battles against both rebelling regions. After Arya Tadah's retirement, Gajah Mada was picked as mahapatih in 1334.[18] It was during Gajah Mada's reign as mahapatih, around the year 1345, that the famous Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta visited Sumatra.

Palapa oath and empire expansion

It is said that it was during his appointment as mahapatih under queen Tribhuwanatunggadewi that Gajah Mada took his famous oath, the Palapa Oath or Sumpah Palapa. The telling of the oath is described in the Pararaton (Book of Kings), an account of Javanese history that dates from the 15th or 16th century:

“Sira Gajah Mada pepatih amungkubumi tan ayun amukita palapa, sira Gajah Mada : Lamun huwus kalah nusantara Ingsun amukti palapa, lamun kalah ring Gurun, ring Seram, Tanjungpura, ring Haru, ring Pahang, Dompo, ring Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Temasek, samana ingsun amukti palapa “

"Gajah Mada, the prime minister, said he will not taste any spice. Said Gajah Mada : If Nusantara (Nusantara= Nusa antara= external territories) has been defeated, I will not taste "palapa" ("fruits and/or spices"). I will not if the domain of Gurun, domain of Seram, domain of Tanjungpura, domain of Haru, Pahang, Dompo, domain of Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Tumasik (Singapore), in which case I will never taste any spice."

While often interpreted literally to mean that Gajah Mada would not allow his food to be spiced (palapa is the prose combination of pala and apa, referring to any fruits/spices), the oath is sometimes interpreted to mean that Gajah Mada would abstain from all earthly pleasures until he conquered the entire known archipelago for Majapahit.

Even his closest friends were at first doubtful of his oath, but Gajah Mada kept pursuing his dream to unify Nusantara under the glory of Majapahit. Soon he conquered the surrounding territory of Bedahulu (Bali) and Lombok (1343). He then sent the navy westward to attack the remnants of the thalassocratic kingdom of Sriwijaya in Palembang. There he installed Adityawarman, a Majapahit prince, as vassal ruler of the Minangkabau in West Sumatra.

He then conquered the first Islamic sultanate in Southeast Asia, Samudra Pasai, and another state in Svarnadvipa (Sumatra). Gajah Mada also conquered Bintan, Tumasik (Singapore), Melayu (now known as Jambi), and Kalimantan.

At the resignation of queen Tribuwanatunggadewi, her son, Hayam Wuruk (ruled 1350–1389), became king. Gajah Mada retained his position as mahapatih under the new king and continued his military campaign by expanding eastward into Logajah, Gurun, Seram, Hutankadali, Sasak, Buton, Banggai, Kunir, Galiyan, Salayar, Sumba, Muar (Saparua), Solor, Bima, Wandan (Banda), Ambon, Timor, and Dompo.

He thus effectively brought the modern Indonesian archipelago under Majapahit control, which spanned not only the territory of today's Indonesia but also that of Temasek (the historical name for Singapore), and the states comprising modern-day Malaysia, Brunei, the southern Philippines and East Timor.

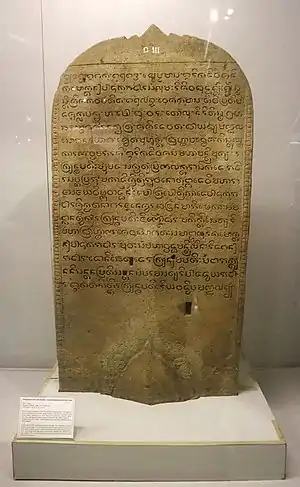

According to the Gajah Mada inscription, dated 1273 Saka (1351 CE), in the month of Wesakha, Sang Mahamantrimukya Rakryan Mapatih Mpu Mada (Gajah Mada) commanded, created and inaugurated a sacred building of Caitya, dedicated for the late Paduka Bhatara Sang Lumah ri Siwa Buddha (King Kertanegara) who had died in 1214 Saka (1292 CE) in the month of Jyesta. The inscription was discovered in Singosari subdistrict, Malang, East Java, and was written in Old Javanese script and language. The caitya or temple mentioned in this inscription is possibly Singhasari temple. The special reverence to King Kertanegara of Singhasari demonstrated by Gajah Mada suggests that the mahapatih honoured the late king tremendously, and possibly the two are related. Some historian suggests that possibly Kertanegara was Gajah Mada's grandfather.[19]

Bubat Incident

.jpg.webp)

In 1357, the only remaining state refusing to acknowledge Majapahit's hegemony was Sunda, in West Java, bordering the Majapahit Empire. King Hayam Wuruk intended to marry Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi, a princess of Sunda and the daughter of Sunda's king. Gajah Mada was given the task to go to the Bubat square in the northern part of Trowulan to welcome the princess as she arrived with her father and escort to Majapahit palace.

Gajah Mada took this opportunity to demand Sunda submission to Majapahit rule. While the Sunda King thought that the royal marriage was a sign of a new alliance between Sunda and Majapahit, Gajah Mada thought otherwise. He stated that the Princess of Sunda was not to be hailed as the new queen consort of Majapahit, but merely as a concubine, as a sign of submission of Sunda to Majapahit. This misunderstanding led to embarrassment and hostility, which quickly rose into a skirmish and then the full-scale Battle of Bubat. The Sunda King with all of his guards as well as the royal party were overwhelmed by Majapahit troops and subsequently killed in the field of Bubat. Tradition holds that the heartbroken princess, Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi, committed suicide.

Hayam Wuruk was deeply shocked by the tragedy. Majapahit courtiers, ministers and nobles blamed Gajah Mada for his recklessness, and the brutal consequences were not to the taste of the Majapahit royal family. Gajah Mada was promptly demoted and spent the rest of his days at the estate of Madakaripura in Probolinggo in East Java.

Death

Gajah Mada died in obscurity in 1364, at the age of 74.[4]: 240 King Hayam Wuruk considered the power Gajah Mada had accumulated during his time as mahapatih too much to handle for a single person. Therefore, the king split the responsibilities that had been Gajah Mada's, between four separate new mahamantri (equal to ministries), thereby probably increasing his own power. King Hayam Wuruk, who is said to have been a wise leader, was able to maintain the hegemony of Majapahit in the region that was gained during Gajah Mada's service. However, Majapahit slowly fell into decline after the death of Hayam Wuruk.

Legacy

His reign helped further Indianisation of Javanese culture through the spread of Hinduism and sanskritization.[4][6]

The Blahbatuh royal house in Gianyar, Bali, has been performing Gajah Mada's mask dance drama ritually for the past 600 years. The mask of Gajah Mada has been protected and brought to life every couple of years to unite and harmonize the world, this sacred ritual was intended to bring peace to Bali.[20]

Gajah Mada's legacy is important for Indonesian Nationalism, and invoked by the Indonesian Nationalist movement in the early 20th century. The Nationalists prior to the Japanese invasion, notably Sukarno and Mohammad Yamin, often cited Gajah Mada's oath and Nagarakretagama as the inspiration and a historical proof of Indonesian past greatness — that Indonesians could unite, despite vast territory and various cultures. The Gajah Mada campaign that united the far flung islands within the Indonesian archipelago under Majapahit suzerainty, was used by Indonesian nationalists to argue that an ancient form of unity had existed prior to Dutch colonialism.[21] Thus, Gajah Mada was a great inspiration during the Indonesian National Revolution for independence from Dutch colonization.

In 1942, only 230 Indonesian natives held a tertiary education. The Republicans sought to mend the Dutch apathy and established the first state university, which freely admitted native pribumi Indonesians. Universitas Gadjah Mada, in Yogyakarta is named in honour of Gajah Mada and was completed in 1945, and had the honour of being the first Medicine Faculty freely open to natives.[22][23][24]

Launched on 9 July 1976, Indonesia's first telecommunication satellite was called Satelit Palapa signifying its role in uniting the vast archipelagic nation.

The Army Military Police Corps of the Indonesian Army has honored Gajah Mada as their unit symbol. The symbol of the Army MP corps also has the picture of Gajah Mada.

Many cities in Indonesia have streets named after Gajah Mada, such as Jalan Gajah Mada and Jalan Hayam Wuruk. There is a brand of badminton shuttlecock named after him as well.

Popular culture

- Gajah Mada appeared in the expansion pack Brave New World for the PC video game Sid Meier's Civilization V as the leader of the Indonesian civilization.

- Gajah Mada has a campaign for the Malay civilization in the Age of Empires II expansion pack, Rise of the Rajas. The campaign revolves around the establishment of the Majapahit empire with the Mongol invasion, the conquest of the archipelago after the Palapa Oath and the Bubat Tragedy that led to his downfall.

- Gajah Mada is also mentioned as Prime Minister of Majapahit Empire in the anime Joukamachi no Dandelion in episode 10.

See also

Notes

- The deification of Gajah Mada as Brajanata and Bima indicated that he is Shiva devotee, but the religion of Majapahit itself is a mixture (syncretic) Hindu-Buddhist, also known as Shaiva-Buddhist.

- It is very possible that Gajah Mada still played a role in Majapahit after the Bubat incident. Munandar interpreted that he led the attack on Dompo with Admiral Wiramandalika Mpu Nala. The interpretation of Gajah Mada's role in Padompo can be seen in the literary collection of the Sultanate of Bima entitled Cerita Asal Bangsa Jin dan Segala Dewa-Dewa (The Story of the Origin of the Jinn and All the Devas), only that Gajah Mada's name is not mentioned directly but is likened to Bima. The description of the story has also been covered with various myths, legends, fairy tales, as well as contemporary historical events when the manuscript was first composed in the 17th and 19th centuries. See Munandar, 2010: 99–100.

References

- Pigeaud, 1960: 83

- Munandar, 2010: 127

- Munandar, 2010: 77

- Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824803681.

- Pradipta, Budya (2004). "Sumpah Palapa Cikal Bakal Gagasan NKRI" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2009.

- Mark Juergensmeyer and Wade Clark Roof, 2012, Encyclopedia of Global Religion, Volume 1, Page 557.

- "Majapahit Story : The History of Gajah Mada". Memory of Majapahit. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Oktorino, Nino (2020). Hikayat Majapahit - Kebangkitan dan Keruntuhan Kerajaan Terbesar di Nusantara. Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo. pp. 128–129.

- Darmajati, Danu (29 December 2015). "Sejarawan: Wajah Gajah Mada Karya M Yamin Pertama Ada Tahun 1945". Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Berg, Kindung Sundāyana (Kidung Sunda C), Soerakarta, Drukkerij “De Bliksem”, 1928.

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (6 August 2018). "The Golden Armor of Gajah Mada". Nusantara Review. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Munandar, 2010: 121

- Munandar, 2010: 116–117

- Munandar, 2010: 116

- Munandar, 2010: 118

- Munandar, 2010: 12–13

- Sobirin, Nanang (17 October 2021). "Dyah Gitarja Nama Kecil Ratu Tribhuwana Tunggadewi yang Turun Langsung Tumpas Pemberontakan Sedeng-Keta". SINDOnews.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- Ningsih, Widya Lestari (5 August 2021). "Pemberontakan Sadeng dan Keta Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "Siapa Sebenarnya Kakek Gajah Mada?". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). 30 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Sertori, Trisha (16 June 2010). "The mask of unity". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Wood, Michael. "The Borderlands of Southeast Asia Chapter 2: Archaeology, National Histories, and National Borders in Southeast Asia" (PDF): 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Stephen Lock, John M. Last, George Dunea. The Oxford illustrated companion to medicine - Oxford Companions Series-Oxford reference online. Oxford University Press US: 2001. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. 891 pages: p. 765

- James J. F. Forest, Philip G. Altbach. Volume 18 of Springer international handbooks of education: International handbook of higher education, Volume 1. Springer: 2006. ISBN 1-4020-4011-3. 1102 pages. p. 772

- R. B. Cribb, Audrey Kahin. Volume 51 of Historical dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East: Historical dictionary of Indonesia. Scarecrow Press: 2004. ISBN 978-0-8108-4935-8. 583 pages. p. 133

Sources

- Munandar, Agus Aris (2010). Gajah Mada: Biografi Politik. Jakarta: Komunitas Bambu. ISBN 978-979-3731-72-8.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1960). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History : The Nāgara-Kĕrtāgama by Rakawi Prapañca of Majapahit, 1365 A.D., Volume III: Translations (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-94-011-8772-5.

- Yamin, Muhammad (1945). Gadjah Mada, Pahlawan Persatoean Noesantara. Balai Poestaka. ISBN 9794073237.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_last_quarter_of_the_10th%E2%80%93first_half_of_the_11th_century.jpg.webp)