Religion in Turkmenistan

The Turkmen of Turkmenistan, are predominantly Muslims. According the U.S. Department of State's International Religious Freedom Report for 2022,

According to U.S. government estimates, the country is 89 percent Muslim (mostly Sunni), 9 percent Eastern Orthodox, and 2 percent other. There are small communities of Jehovah's Witnesses, Shia Muslims, Baha’is, Roman Catholics, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, and evangelical Christians, including Baptists and Pentecostals. Most ethnic Russians and Armenians identify as Orthodox Christian and generally are members of the Russian Orthodox Church or Armenian Apostolic Church. Some ethnic Russians and Armenians are also members of smaller Protestant groups. There are small pockets of Shia Muslims, consisting largely of ethnic Iranians, Azeris, and Kurds, some located in Ashgabat, with others along the border with Iran and in the western city of Turkmenbashy.[2]

The great majority of Turkmen readily identify themselves as Muslims and acknowledge Islam as an integral part of their cultural heritage.[3]

The country of Turkmenistan encourages the conceptualization of "Turkmen Islam," or worship that is often mixed with veneration of elders and saints, life-cycle rituals, and Sufi practices.[3]

Since Turkmenistan's independence saw an increase in religious practices and the development of institutions like the Muftiate and the building of mosques, today it is often regulated.[3]

The government leadership of Turkmenistan often uses Islam to legitimize its role in society by sponsoring holiday celebrations such as iftar dinners during Ramadan and presidential pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. This sponsorship has validated the country's two presidents (Nyýazow and Berdimuhamedow) as pious Turkmen, giving them an aura of cultural authority.[3]

Religious demography

The country has an area of 488,100 square kilometres (188,457 sq mi) and an officially declared population of 5.5- to 6 million, though unofficial sources indicate the resident population may not exceed five million.[4] Official statistics regarding religious affiliation are not available. According to the Government's most recent published census (1995)[5] ethnic Turkmen constitute 77 percent of the population. Minority ethnic populations include Uzbeks (9.2 percent), Russians (6.7 percent), and Kazakhs (2 percent). Armenians, Azeris, and other ethnic groups comprise the remaining 5.1 percent. The unpublished 2012 census reportedly counted Turkmen as 85.6 percent, followed by 5.8 percent Uzbeks and 5.1 percent ethnic Russians.[4] The majority religion is Sunni Islam, and Russian Orthodox Christians constitute the largest religious minority. The level of active religious observance is unknown.

Since independence, Islam has been revived but it is tightly controlled. During the Soviet era, only four mosques operated; now there are 698. Ethnic Turkmens, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Balochs and Pashtuns living in Mary Province are predominantly Sunni Muslim. There are small pockets of Shi'a Muslims, many of whom are ethnic Iranians, Azeris, or Kurds living along the border with Iran and in Turkmenbashy.

While the 1995 census indicated that ethnic Russians composed almost 7 percent of the population, subsequent emigration to Russia and elsewhere has reduced considerably this proportion. Most ethnic Russians and Armenians are Orthodox Christians. There are 12 Russian Orthodox churches, four of which are in Ashgabat.[6] An archpriest resident in Ashgabat leads the Orthodox Church within the country. Until 2007 Turkmenistan fell under the religious jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox archbishop in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, but since then has been subordinate to the Archbishop of Pyatigorsk and Cherkessia.[7] There are no Russian Orthodox seminaries in Turkmenistan.

Ethnic Russians and Armenians also comprise a significant percentage of members of unregistered religious congregations; ethnic Turkmen appear to be increasingly represented among these groups as well. There are small communities of the following unregistered denominations: the Roman Catholic Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, Jews, and several evangelical Christian groups including "Separate" Baptists, charismatic groups, and an unaffiliated, nondenominational group.

Small communities of Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, the Society for Krishna Consciousness and the Baháʼí Faith have registered with the Government. In May 2005 the Greater Grace World Outreach Church of Turkmenistan, the International Church of Christ, the New Apostolic Church of Turkmenistan, and two groups of Pentecostal Christians were able to register. There are also the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Greater Grace World Outreach Church, the Protestant Word of Life Church.

A very small community of ethnic Germans, most of whom live in and around the city of Sarahs, reportedly included practicing Lutherans. Approximately one thousand ethnic Poles live in the country; they have been largely absorbed into the Russian community and consider themselves Russian Orthodox. The Catholic community in Ashgabat, which includes both citizens and foreigners, meet in the chapel of the Apostolic Nunciature. There are a very small number of foreign missionaries, although the extent of their activities is unknown.

An estimated two hundred Jews live in the country in 2022.[2] Most are members of families who came from Ukraine during World War II. There are some Jewish families living in Turkmenabat, on the border with Uzbekistan, part of the Bukharan Jewish community, a historical reference to the Khanate of Bukhara that until the Russian conquest ruled that area. There are no synagogues;[8] the last synogogue was turned into a gym during the Soviet era. Some in the community gather for religious observances but collectively Jews have not opted to register as a religious group. There are no reports of harassment of Jews.

Islam and its history in Turkmenistan

Islam came to the Turkmen primarily through the activities of Sufi shaykhs rather than through the mosque and the "high" written tradition of sedentary culture. These shaykhs were holy men critical in the process of reconciling Islamic beliefs with pre-Islamic belief systems; they often were adopted as "patron saints" of particular clans or tribal groups, thereby becoming their "founders." Reformulation of communal identity around such figures accounts for one of the highly localized developments of Islamic practice in Turkmenistan.[9]

Integrated within the Turkmen tribal structure is the "holy" tribe called övlat . Ethnographers consider the övlat, of which six are active, as a revitalized form of the ancestor cult injected with Sufism. According to their genealogies, each tribe descends from Muhammad through one of the Four Caliphs. Because of their belief in the sacred origin and spiritual powers of the övlat representatives, Turkmen accord these tribes a special, holy status. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the övlat tribes became dispersed in small, compact groups in Turkmenistan. They attended and conferred blessings on all important communal and life-cycle events, and also acted as mediators between clans and tribes. The institution of the övlat retains some authority today. Many of the Turkmen who are revered for their spiritual powers trace their lineage to an övlat, and it is not uncommon, especially in rural areas, for such individuals to be present at life-cycle and other communal celebrations.[9]

In the Soviet era, all religious beliefs were attacked by the communist authorities as superstition and "vestiges of the past." Most religious schooling and religious observance were banned, and the vast majority of mosques were closed. An official Muslim Board of Central Asia with a headquarters in Tashkent was established during World War II to supervise Islam in Central Asia. For the most part, the Muslim Board functioned as an instrument of propaganda whose activities did little to enhance the Muslim cause. Atheist indoctrination stifled religious development and contributed to the isolation of the Turkmen from the international Muslim community. Some religious customs, such as Muslim burial and male circumcision, continued to be practiced throughout the Soviet period, but most religious belief, knowledge, and customs were preserved only in rural areas in "folk form" as a kind of unofficial Islam not sanctioned by the state-run Spiritual Directorate.[9]

Religion after Independence

Since 1991, Islam and minority religions have been allowed to resume, though under tight government control.[10] Mosques were reopened, and Russian Orthodox Christian churches were allowed to operate; a small number of Protestant Christian churches have been allowed to register and operate. Large new mosques have been built in major cities, including the Türkmenbaşy Ruhy Mosque in Ashgabat, constructed by Bouygues of France. Instruction in Islam is authorized in one educational institution, Turkmen State University, which includes a Department of Theology.[11]

Religion remains under government supervision. The mufti is appointed by the president. Importation of religious literature must be approved by the government.[2]

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom reported in 2020

The 2016 Religion Law asserts that Turkmenistan is a secular state with religious freedom. However, it requires religious groups to register with the Ministry of Justice under intrusive criteria (including having 50 adult citizen founders), prohibits any activity by unregistered groups, requires that the government be informed of all foreign financial support, bans worship in private homes and private religious education, and prohibits the wearing of religious garb in public except by clerics. All religious activity is overseen by the State Commission on Religious Organizations and Expert Evaluation of Religious Information Resources (SCROEERIR), which approves the appointment of religious leaders, the building of houses of worship, the import and publication of religious literature, and the registration of all religious organizations. The law does not specify the criteria for gaining SCROEERIR approval, which enables arbitrary enforcement. The registration process requires religious organizations to provide the government with detailed information about founding members, including names, addresses, and birth dates. Registered communities must reregister every three years, and religious activity is not permitted in prisons or the military.[10]

The U.S. Department of State reported in 2019

The constitution provides for the freedom of religion and for the right of individuals to choose their religion, express and disseminate their religious beliefs, and participate in religious observances and ceremonies. The constitution maintains the separation of government and religion, stipulating religious organizations are prohibited from "interference" in state affairs. The law on religion requires all religious organizations, including those previously registered under an earlier version of the law, to reregister with the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) every three years to operate legally. According to religious organizations, government security forces continued to surveil religious organizations and ban the importation of religious literature, and it remained difficult to obtain places of worship.[12]

In 2022, many religious groups reported an increase in young people showing an interest in religion and spirituality; this is said to be a result of growing up after the Soviet era, and a response to the threat of Covid.[2]

Syncretism in Turkmen Islam

The Russian Academy of Sciences has identified many instances of syncretic influence of pre-Islamic Turkic belief systems on practice of Islam among Turkmen, including placing offerings before trees.[13] The Turkmen word taňry, meaning "God", derives from the Turkic Tengri, the name of the supreme god in the pre-Islamic Turkic pantheon.[14] The Turkmen language features a multitude of euphemisms for "wolf", because of a belief that speaking the actual word while tending a flock of sheep will invoke a wolf's appearance.[15] In other examples of syncretism, some infertile Turkmen women, rather than praying, step or jump over a live wolf to assist them in getting pregnant. Children born subsequently are typically given names associated with wolves; alternatively the mother may visit shrines of Muslim saints.[16] The future is also divined by reading of dried camel dung by special fortune tellers.[17]

Other religions

Christianity

Christianity is the second largest religion in Turkmenistan, accounting for 6.4% of the population or 320,000 according to a 2010 study by Pew Research Center.[18] Around 5.3% or 270,000 of the population of Turkmenistan are Eastern Orthodox Christians.[18]

Protestants account for less than 1% (30,000) of the population of Turkmenistan.[18] There are also very few Catholics in the country - around 95 in total.[19]

Armenians living in Turkmenistan (below 1%) mostly adhere to Armenian Apostolic Church and Russian Orthodox Church.[2]

Hinduism

Hinduism was spread in Turkmenistan by International Society for Krishna Consciousness. ISKCON Hindus are a minority community in Turkmenistan.

A ISKCON representative reported to the U.S. Department of State that harassment from officials had decreased since her group's registration. In October 2006, as part of a general annual prison amnesty, former President Niyazov released imprisoned ISKCON follower Ceper Annaniyazova, who had been sentenced to seven years in prison in November 2005 for having illegally crossed the border in 2002.

Baháʼí Faith

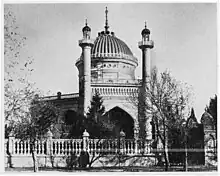

The Baháʼí Faith in Turkmenistan dates to before Russia's advances into the region, while the area was under Persian influence.[20] By 1887 a community of Baháʼí refugees from religious violence in Persia had founded a religious center in Ashgabat.[20] While the Baháʼí Faith spread across the Russian Empire[21] and attracted the attention of scholars and artists,[22] the Baháʼí community in Ashgabat built the first Baháʼí House of Worship, elected one of the first Baháʼí local administrative institutions and was a center of scholarship. However, during the Soviet period religious persecution caused the Baháʼí community almost to disappear. Nevertheless, Baháʼís who moved into the regions in the 1950s did identify individuals still adhering to the religion. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, Baháʼí communities and their administrative bodies started to develop across the nations of the former Soviet Union.[23] In 1994 Turkmenistan elected its own National Spiritual Assembly;[24] however, laws passed in 1995 in Turkmenistan required 500 adult religious adherents in each locality for registration and no Baháʼí community in Turkmenistan could meet this requirement.[25] As of 2007 the religion had still failed to reach the minimum number of adherents to register[26] and individuals have seen their homes raided for Baháʼí literature.[27]

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is guaranteed by Article 11 of the Constitution of Turkmenistan. However, like other human rights, in practice it does not exist. Former President Saparmurat Niyazov's book of spiritual writings, the Ruhnama, is imposed on all religious communities. According to Forum 18, despite international pressure, the authorities severely repress all religious groups, and the legal framework is so constrictive that many prefer to exist underground rather than have to pass through all of the official hurdles. Protestant Christian adherents are affected, in addition to groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses, Baháʼí, and International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Jehovah's Witnesses have been fined, imprisoned and suffered beatings for their faith or due to being conscientious objectors;[10][28] in 2022 they reported no arrests, but noted that the government continues to call them for military service and do not offer exemptions for conscientious objectors.[2]

A 2009 CIA report regarding religious freedom in Turkmenistan reads:

"A survey of bookstores in central Ashgabat to check the availability of the Quran, the holy book of Muslims, revealed that the book was practically unavailable in state stores except for rare cases of second-hand copies. The only other places where the Quran could be bought were at an Iranian bookshop and from a private bookseller. During the visit to the Iranian store, the clerk explained that to import and sell the Quran in Turkmenistan, the store needed approval by the Presidential Council on Religious Affairs. In a predominantly Muslim society, the unavailability of the Quran for purchase seems to be an anomaly. The authorities' strict control over the availability of religious literature, including Islamic literature, highlights the state's insecurity about the impact that the unrestricted practice of religion could have on the current status quo in Turkmen society ... In general, the majority of Turkmen have a Quran in Arabic in their homes. Even if they cannot read Arabic, the fact of having the holy book is believed to protect a family from evil and misfortune. For an explanation of the Quran, most people rely on imams, who are appointed by the Council on Religious Affairs at national, provincial, city and district levels. The scarcity of the Quran in a familiar language leaves people little choice but to turn to the state-appointed imams for the "correct" interpretation of the book, a further sign of the government's policy of strict control over religious life in the country."

In 2023, the country was scored zero out of 4 for religious freedom;[29] it was noted that restrictions have tightened since 2016. In the same year it was ranked the 26th worst place in the world to be a Christian.[30]

See also

References

- "The World Factbook". ca-barometer.org. November 2 – December 24, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- US State Dept 2022 report

- "Religion and the Secular State in Turkmenistan – Silk Road Paper". Institute for Security and Development Policy. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- Goble, Paul (February 10, 2015). "Unpublished Census Provides Rare and Unvarnished Look at Turkmenistan". Jamestown Foundation.

- Results of each subsequent census have remained unpublished.

- "Православие в Туркменистане / Приходы" (in Russian).

- "Православие в Туркменистане / История и современность" (in Russian).

- World Jewish Congress website, Communities page

- Larry Clark, Michael Thurman, and David Tyson. "Turkmenistan". A Country Study: Turkmenistan (Glenn E. Curtis, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (March 1996). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Turkmenistan Chapter - 2020 Annual Report" (PDF). U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. 2020.

- "TSU About us". Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- "Turkmenistan 2019 International Religious Freedom REPORT" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 2019.

- Demidov, Sergey Mikhaylovich (2020). Растения и Животные в Легендах и Верованиях Туркмен (PDF). Moscow: Staryy sad. pp. 22–23.

- Demidov, Sergey Mikhaylovich (2020). Растения и Животные в Легендах и Верованиях Туркмен (PDF). Moscow: Staryy sad. pp. 143–144.

- Demidov, Sergey Mikhaylovich (2020). Растения и Животные в Легендах и Верованиях Туркмен (PDF). Moscow: Staryy sad. pp. 151–152. Demidov cites the Turkmen proverb, "Gurt agzasan, gurt geler" (Mention the wolf, the wolf comes), in explaining why the original Turkic word for wolf, böri, is virtually never used.

- Demidov, Sergey Mikhaylovich (2020). Растения и Животные в Легендах и Верованиях Туркмен (PDF). Moscow: Staryy sad. pp. 155–156.

- Demidov, Sergey Mikhaylovich (2020). Растения и Животные в Легендах и Верованиях Туркмен (PDF). Moscow: Staryy sad. p. 356.

- "Religions in Turkmenistan | PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- "Turkmenistan, Statistics by Diocese, by Catholic Population [Catholic-Hierarchy]". Catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- Momen, Moojan. "Turkmenistan". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv (2007). "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Tolstoy, Leo". A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 340. ISBN 1-85168-184-1. Retrieved October 20, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. Vol. 1998, no. 8. pp. 35–44.

- Hassall, Graham; Universal House of Justice. "National Spiritual Assemblies statistics 1923–1999". Assorted Resource Tools. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- Wagner, Ralph D. "Turkmenistan". Synopsis of References to the Baháʼí Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991–2000. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- U.S. State Department (September 14, 2007). "Turkmenistan - International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- Corley, Felix (April 1, 2004). "Turkmenistan: Religious communities theoretically permitted, but attacked in practice?". F18News.

- "Turkmenistan Imprisons Jehovah's Witnesses for Their Faith". Archived from the original on September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-08

- Open Doors website, retrieved 2023-08-08