Dakotaraptor

Dakotaraptor (meaning “thief from Dakota”) is a potentially chimaeric[2] genus of large dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived in western North America during the Late Cretaceous period. The remains have been found in the Maastrichtian-aged Hell Creek Formation, dated to the very end of the Mesozoic era, making Dakotaraptor one of the last surviving dromaeosaurids. The remains of D. steini were discovered in a multi-species bonebed.[1] Elements of the holotype and referred specimens were later found to belong to trionychid turtles[3] and further analysis of potential non-dromaeosaurid affinities of the holotype and referred material have not yet been conducted. Phylogenetic analyses of D. steini place it in a variety of positions within Dromaeosauridae.[1][4]

| Dakotaraptor Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian), | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Reconstructed skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Eumaniraptora |

| Clade: | †Deinonychosauria |

| Genus: | †Dakotaraptor DePalma et al. 2015[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Dakotaraptor steini DePalma et al. 2015[1] | |

Discovery and naming

In 2005, paleontologist Robert DePalma in Harding County, South Dakota discovered a fluvial bonebed bearing the remains of a variety of dinosaurian and non-dinosaurian remains, which yielded a partial skeleton attributed by DePalma to a large dromaeosaurid. Subsequently, the same site produced additional dromaeosaurid remains.[5]

In 2015, the type species Dakotaraptor steini was named and described by Robert A. DePalma, David A. Burnham, Larry Dean Martin, Peter Lars Larson, and Robert Thomas Bakker. The generic name, Dakotaraptor, combines a reference to South Dakota and the Dakota people with the Latin word raptor, meaning "plunderer". The specific name, steini, honors paleontologist Walter W. Stein.[1] Dakotaraptor was one of eighteen dinosaur taxa from 2015 to be described in open access or free-to-read journals.[6][7]

The holotype, PBMNH.P.10.113.T, was found in a sandstone layer of the upper Hell Creek Formation, dating to the late Maastrichtian. It consists of a partial skeleton of an adult individual, albeit without a skull. It contains a piece of a back vertebra, ten tail vertebrae, both humeri, both ulnae, both radii, the first and second right metacarpals, three claws of the left hand, a right thighbone, both shinbones, a left astragalus bone, a left calcaneum, the left second, third and fourth metatarsal, the right fourth metatarsal, and the second and third claw of the right foot. An assigned furcula was later excluded from the specimen.[8]

Apart from the remains of the holotype, bones were discovered in the site that also belonged to Dakotaraptor, but which represented a more gracile morph. These included the specimens PBMNH.P.10.115.T (a right shinbone), PBMNH.P.10.118.T (a connected left astragalus and calcaneum), and KUVP 152429 (originally identified as a furcula, but now also excluded from the known remains of Dakotaraptor).[8] Additionally, four isolated teeth were referred (PBMNH.P.10.119.T, PBMNH.P.10.121.T, PBMNH.P.10.122.T, and PBMNH.P.10.124.T). These fossils are part of the collection of The Palm Beach Museum of Natural History. Other referred fossils are KUVP 156045 (an isolated tooth)[1] and NCSM 13170 (a third supposed furcula that was later identified as not belonging to Dakotaraptor).[8]

The elements originally identified as the furcula of Dakotaraptor were U- to V-shaped, suggested by the describers to be similar to many other dromaeosaurids, such as Velociraptor, and even the large spinosaurid theropod Suchomimus. In 2015, a study by Victoria Megan Arbour et al. proposed that the presumed Dakotaraptor furculae in fact represented a part of a turtle’s armor, the entoplastron of Axestemys splendida, a member of Trionychidae.[3] In 2016, DePalma et al. recognized that none of the referred furculae actually belonged to Dakotaraptor and excluded them from its hypodigm.[8]

Description

Size

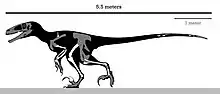

Dakotaraptor is exceptionally large for a dromaeosaurid, with an estimated adult length of 5.5 m (18 ft).[1] In 2016, other estimations suggested a length of 4.35-6 m (14.3-19.7 ft) and a weight of 220-350 kg (485-772 lbs).[9][10]

This approaches the size of one of the largest known dromaeosaurids, Utahraptor.[11] Dakotaraptor, however, does not have the proportions and adaptations of Utahraptor, but more closely resembles smaller dromaeosaurids, like Deinonychus.[1]

Distinguishing traits

Apart from its large size, the description of 2015 indicated some additional distinguishing traits. On the fourth foot claw, the boss that serves as an attachment for the tendon of the flexor muscle is reduced in size. The "blood groove" on the outer side of the fourth claw of the foot, towards the tip, is fully enclosed over half of its length, forming a bony tubular structure. The second and third claws of the foot have sharp keels at their undersides. The second foot claw, the "sickle claw", equals 29% of the thighbone length. On the shinbone, the crista fibularis, the crest that contacts the calfbone, is long and lightly built, with a height that does not exceed 9% of the crest length. The upper edge of this crest ends in a hook. On the second metacarpal, of the two condyles that contact the finger, the inner one is almost as large as the outer one. The outer side of the second metacarpal has but a shallow groove for the ligament that connects it to the third metacarpal. When the arm is seen in a flat position, of the second metacarpal, the edge between the wrist joint and the upper shaft is straight in top view. The teeth have fifteen to twenty denticles per 5 millimetres (0.20 in) on the rear edges and twenty to twenty-seven denticles on the front edges.[1]

Vertebral column

The vertebrae of the back are highly pneumatised, filled with trabecular bone that shows many air spaces. On the middle tail vertebrae, the front joint processes, the prezygapophyses, are extremely elongated with an estimated intact length of 70 centimetres (28 in), spanning about ten vertebrae. This helps to stiffen out the tail.[1]

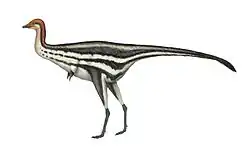

Arms

The wing of Dakotaraptor was given much attention in the describing article. Here, “wing” is used as an anatomical descriptive term not related to its functionality, since Dakotaraptor was flightless. This is similar to the term “wing” for the same appendages in ostriches, emus, and other flightless birds. It is meant to express that the arm is equipped with long feathers resembling those of flight feathers in birds that can actually fly. Many of the wing bones were discovered (humerus, radius, ulna, two of the three metacarpal wrist bones, and parts of the finger digits), so the wing is very complete. The humerus, the upper arm bone, is relatively long, slender, and somewhat bent to the inside. The most notable anatomical feature is the row of very prominent bumps along a ridge on the lower edge of the ulna, one of the forearm bones. These are called ulnar papillae, more commonly known as quill knobs. In birds and some other theropod dinosaurs, these bumps were spots for reinforced attachment of the remiges, or wing feathers. When quill knobs are present, this is considered a strong indication that the animal had long remiges on the wings. Since quill knobs are rare in the fossil record, paleontologists mainly relied on phylogenetic bracketing to determine if a species was likely to have had wing feathers - if a relative on a "higher" branch of the evolutionary tree had the feathers and one on a "lower" down branch had them too, then a species in the middle position likely did as well. Dakotaraptor’s quill knobs show that the animal unequivocally had prominent wing feathers, making it the largest dromaeosaurid with confirmed plumage of that type. The quill knobs of Dakotaraptor have a diameter of about 8–10 millimetres (0.31–0.39 in), which shows that these feathers were rather large. It was estimated that a complete series might include fifteen of these papillae ulnares. The ulna is 36 centimetres (14 in) long and the other lower arm bone, the radius, measures 32 centimetres (13 in). The hand bones show that their joints allowed for little mobility. The wingspan of Dakotaraptor was estimated at 120 centimetres (47 in), not taking into account possible primary remiges longer than the hand.[1]

The second metacarpal of the metacarpus of the hand, the bone that primary remiges attach to, also had a flat bony shelf as its dorsal surface. The shelf made a perfect spot for the primary feathers to lay across in their life-attachment.[1]

Legs

Overall, the legs of Dakotaraptor are lightly built and have long elements, contrary to the robust, stocky legs of Utahraptor. Dakotaraptor more closely resembles the agile, springy smaller dromaeosaurids and would have been well-suited to running and pursuit predation. The length of the thighbone is 558 millimetres (22.0 in). It is relatively shorter and more lightly built than that of Utahraptor. On the contrary, the shinbone is rather elongated. The holotype shinbone is, with a length of 678 millimetres (26.7 in), the longest dromaeosaurid tibia known. It is 22% longer than the thighbone, indicating high running capability. The shinbone's cnemial crest has a sharp corner pointing to the front. Its fibular crest ends in a hook-shaped process pointing up, a condition that is unique in the entirety of Theropoda. The astragalus and calcaneum, the upper ankle bones, are fused and similar to those in Bambiraptor. The top of the calcaneum has but a small contact facet for the calfbone, indicating that this fibula must have had a very narrow lower end.[1] The metatarsus has an estimated length of 32 centimetres (13 in), which makes it rather long when compared to the remainder of the leg.[1]

The foot claws of Dakotaraptor include a typical dromaeosaurid raptorial second claw, or "sickle claw", which was used for killing or holding down prey. It is large and robust with a diameter of 16 centimetres (6.3 in) and a length of 24 centimetres (9.4 in) measured along the outer curve. This equals 29% of the length of the thighbone (as previously mentioned), compared to 23% in Deinonychus. The claw is transversely flattened and has a droplet-shaped cross-section. The flexor tubercle, a large bump near the base, served as an attachment site for flexor muscles - the larger it was, the greater the slashing strength. Dakotaraptor has a flexor tubercle that is larger relative to overall claw size than it is in other discovered dromaeosaurids, potentially giving it the strongest slashing strength of any known member of this group. The flexor tubercle on the third claw of the foot is almost non-existent, being very reduced in size compared to other dromaeosaurids. This suggests a more minimized use of that claw. As these are the bony cores of the claws, they would have been covered in a keratinous sheath that extended the "nail" and ended in a sharp tip. The third claw is keeled too, but is much smaller, with a tip to joint length of 7 centimetres (2.8 in) and a curve length of 9 centimetres (3.5 in). The groove on its outer side towards the tip ends in a bone tunnel, which is a rare condition.[1]

Classification

Dakotaraptor was placed in Dromaeosauridae. A cladistic analysis showed that it was the sister taxa of Dromaeosaurus. They again formed a clade with Utahraptor, of which clade Achillobator was the direct side branch. Despite being related to other large dromaeosaurids, Dakotaraptor was suggested to represent a separate fourth instance of dromaeosaurid size increase, besides Deinonychus, Unenlagia, and the Achillobator plus Utahraptor clade.[1]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A recent study conducted by Hartman et al. 2019 recovered a placement of Dakotaraptor in Unenlagiidae.[12] If this study proves correct, then Dakotaraptor would have been one of the northernmost genera of Unenlagiine known.

| Unenlagiidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the recently performed phylogenetic analysis by Currie and Evans in 2019, Dakotaraptor was again recovered as an eudromaeosaur, though the authors noted that the holotype may not represent one individual.[13]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In their description of Dineobellator, Jasinski et al. (2020) (using the same dataset as Currie and Evans(2019)) again recovered this position for Dakotaraptor, but also noted the likely status of Dakotaraptor as a chimaera, casting doubt on this placement as too basal because of the potential composite nature of the taxon.[2]

Possible synonymy with Acheroraptor

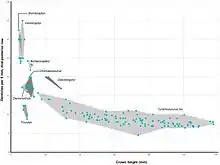

Acheroraptor temertyorum is another theropod from the Hell Creek Formation, named in 2013 for a lower jaw, a maxilla, and some teeth. Acheroraptor was diagnosed by multiple features, including the possession of ridges on its teeth.[14] Teeth are the only overlapping features between Acheroraptor and Dakotaraptor. However Acheroraptor is significantly smaller and differs from Dakotaraptor only in that it possesses vertical ridges on the tooth crowns.[15] Andrea Cau noted that, though Dakotaraptor is known from individuals of differing sizes, some of the smaller specimens are also fully mature and it is possible that the size difference means Dakotaraptor is simply a different species or size morph of Acheroraptor. A phylogenetic analysis presented by Cau, mainly relying on fragmentary specimens, did not result in a close relationship between the two.[15]

Paleobiology

The keeled claw of the second toe, the "sickle claw", was used to bring down prey and had a more robust flexor tubercle than that of Utahraptor. On the contrary, the third foot claw was relatively smaller in size than with other dromaeosaurids and seems not to have had an important function in attacking prey.[1]

Two morphs, a robust one and a gracile one, were present in the fossil material. A study of the bone histology showed that both morphs were adults, so the lighter build of some bones was not caused by a young age. Individual variety or pathologies might account for the difference, but the simplest explanation is sexual dimorphism. It can as yet not be deduced which morph was male and which morph was female.[1]

On the ulna of the lower arm, wide quill knobs are present, attachment points for large pennaceous feathers (as previously mentioned). Adult Dakotaraptor individuals were much too heavy to fly. Despite this flightless condition, the feathers were not reduced. There is a variety of possible alternative functions for its wings, including shielding of eggs, display, intimidation, and keeping balance while pinning down prey with the sickle claw. These functions, however, do not necessitate quill knobs and the describing authors considered it likely that Dakotaraptor descended from a smaller flying ancestor that had them.[1]

Paleoecology

Dakotaraptor is the first medium-sized predator discovered in the Hell Creek Formation (aside from the dubious Nanotyrannus), intermediate in length between the giant tyrannosaurid Tyrannosaurus and smaller Deinonychosaurians, like Acheroraptor.[14] As its tibia was longer than its femur, Dakotaraptor would have had a high running capacity, filling the niche of a pursuit predator. If it was possibly a pack-hunter that cooperated in groups, it could have preyed upon larger herbivores, possibly competing with subadult Tyrannosaurus in the 6–9 metres (20–30 ft) length range. It lived alongside other famous Hell Creek dinosaurs, including the aforementioned Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, Pachycephalosaurus, Ornithomimus, and Edmontosaurus.[1][16][17]

References

- DePalma, R. A.; Burnham, D. A.; Martin, L. D.; Larson, P. L.; Bakker, R. T. (2015). "The First Giant Raptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Hell Creek Formation". Paleontological Contributions (14). doi:10.17161/paleo.1808.18764.

- Jasinski, Steven E.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Dodson, Peter (2020-03-26). "New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the end of the Cretaceous". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 5105. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5105J. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61480-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7099077. PMID 32218481.

- Arbour, V.M.; Zanno, L.E.; Larson, D.W.; Evans, D.C.; Sues, H. (2015). "The furculae of the dromaeosaurid dinosaur Dakotaraptor steini are trionychid turtle entoplastra". PeerJ. 3: e1957. doi:10.7717/peerj.1691. PMC 4756751. PMID 26893972.

- Hartman, Scott; Mortimer, Mickey; Wahl, William R.; Lomax, Dean R.; Lippincott, Jessica; Lovelace, David M. (2019-07-10). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- DePalma, R. A. (2010). Geology, taphonomy, and paleoecology of a unique Upper Cretaceous bonebed near the Cretaceous-Tertiary Boundary in South Dakota (Master of Science thesis). University of Kansas. pp. 227 pp.

- "The Open Access Dinosaurs of 2015". PLOS Paleo. 2016-01-06.

- Connected, Science (2016-01-26). "Discovering Dakotaraptor Steini". Science Connected Magazine. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- DePalma, R.A.; Burnham, D.A.; Martin, L.D.; Larson, P.L.; Bakker, R.T. (2016). "Corrigendum to: The First Giant Raptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Hell Creek Formation". Paleontological Contributions. 16. doi:10.17161/1808.22120.

- Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain: Larousse. p. 275.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd Edition. Princeton University Press. p. 151.

- Mike (4 November 2015). "Dakotaraptor Compared to Utahraptor". Everything Dinosaur Blog. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W. R.; Lomax, D. R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D. M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- Currie, P. J.; Evans, D. C. (2019). "Cranial Anatomy of New Specimens of Saurornitholestes langstoni (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian) of Alberta". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 691–715. doi:10.1002/ar.24241. PMID 31497925. S2CID 202002676.

- Evans, David C.; Larson, Derek W.; Currie, Philip J. (2013-11-19). "A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) with Asian affinities from the latest Cretaceous of North America". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (11): 1041–1049. Bibcode:2013NW....100.1041E. doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1107-5. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 24248432. S2CID 14978813.

- Cau, A. (2015-10-31). "Dakotaraptor... a giant Acheroraptor?". Theropoda.

- Pearson, D. A.; Schaefer, T.; Johnson, K. R.; Nichols, D. J.; Hunter, J. P. (2002). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek Formation in Southwestern North Dakota and Northwestern South Dakota". In Hartman, John H.; Johnson, Kirk R.; Nichols, Douglas J. (eds.). The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the northern Great Plains: An integrated continental record of the end of the Cretaceous. Geological Society of America. pp. 145–167. ISBN 9780813723617. Special Paper 361.

- Arens, N. C.; Jahren, A. H.; Kendrick, D. (2014). "Carbon isotope stratigraphy and correlation of plant megafossil localities in the Hell Creek Formation of eastern Montana, USA". Special Paper of the Geological Society of America. 503: 149–171. doi:10.1130/2014.2503(05). ISBN 9780813725031. S2CID 44089740.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)