Caenagnathus

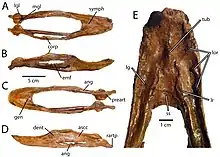

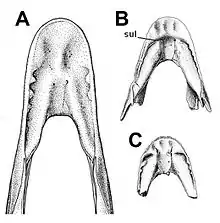

Caenagnathus ('recent jaw') is a genus of caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian dinosaur from the late Cretaceous period (Campanian stage; ~75 million years ago). It is known from partial remains including lower jaws, a tail vertebra, hand bones, and hind limbs, all found in the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Caenagnathus measured about 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long and weighed about 96–100 kg (212–220 lb).[1][2]

| Caenagnathus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype mandible | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Caenagnathidae |

| Subfamily: | †Caenagnathinae |

| Genus: | †Caenagnathus Sternberg, 1940 |

| Species: | †C. collinsi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Caenagnathus collinsi Sternberg, 1940 | |

Description

Caenagnathus was a large oviraptorosaurian, with some specimens suggesting it achieved sizes comparable to its relative Anzu. Like Anzu, it had a toothless lower beak that was shallower in depth than those of elmisaurines. It also shared with Anzu less gracile proportions than those of elmisaurines.[3] Like all oviraptorosaurs, it would most likely have possessed a coat of feathers.

Classification

This dinosaur has a confusing history. In 1936, a set of jaws (CMN 8776) were found, and later given the name Caenagnathus, meaning 'recent jaw'; they were first thought to be those of a bird.[4] In 1988, a specimen from storage since 1923 was discovered and studied. This fossil was used to link the discoveries of several fragmentary oviraptorosaur species into a single dinosaur, which was assigned to the genus Chirostenotes, originally named for a pair of hands that were long considered to come from the same animal as Caenagnathus. Since the first name applied to any of these remains was Chirostenotes, this was the only name recognized as valid for many years.[5] However, Senter and Parrish (2005) doubted the synonymy of Caenagnathus with Chirostenotes, noting that the maxillary remains included in the Epichirostenotes holotype didn't overlap with CMN 8776. A cladistic analysis of Coelurosauria by Senter (2007) found Caenagnathus to fall basally within Caenagnathoidea, while Chirostenotes fell as a derived taxon related to Elmisaurus.[6][7]

The status and relationships of Caenagnathus to other caenagnathid oviraptorosaurians began to be resolved with the discovery of more complete specimens in 2014 and 2015. The description of Anzu wyliei in 2014 represented the first nearly complete caenagnathid, and helped to clarify the differences between the more fragmentary specimens. Phylogenetic analyses found Caenagnathus collinsi to be more closely related to Anzu than to Chirostenotes. A second species which had previously been referred to Caenagnathus, "Caenagnathus" sternbergi, was found to be the sister taxon to the grouping of Anzu and Caenagnathus in one 2014 analysis.[8] In 2015, new fossil remains were found to belong to Caenagnathus collinsi. These appeared to be intermediate in size and anatomy between the smaller Chirostenotes and the larger Anzu, lending support to their hypothesized relationships. These bones can be distinguished from Chirostenotes and contemporary "Leptorhynchos" elegans by features of the limbs, specifically the hand and metatarsals.[1]

| Caenagnathoidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A new Chirostenotes specimen described by Funston and Currie (2020) preserving a mandible provides further evidence that Caenagnathus is a distinct genus from Chirostenotes despite both taxa being part of the Caenagnathidae.[9]

See also

References

- Funston, G. F.; Persons, W. S.; Bradley, G. J.; Currie, P. J. (2015). "New material of the large-bodied caenagnathid Caenagnathus collinsi from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada". Cretaceous Research. 54: 179–187. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.12.002.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- Funston, Gregory (2020-07-27). "Caenagnathids of the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian) of Alberta, Canada: anatomy, osteohistology, taxonomy, and evolution". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 8: 105–153. doi:10.18435/vamp29362. ISSN 2292-1389.

- Sternberg, R.M. (1940). "A toothless bird from the Cretaceous of Alberta". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (1): 81–85.

- Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. (1988). "Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 25 (7): 972–986. Bibcode:1988CaJES..25..972C. doi:10.1139/e88-097.

- Senter, P.; Parrish, J.M. (2005). "Functional analysis of the hands of the theropod dinosaur Chirostenotes pergracilis: evidence for an unusual paleoecological role". PaleoBios. 25: 9–19.

- Senter, P (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (4): 429–463. doi:10.1017/s1477201907002143.

- Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e92022. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992022L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022. PMC 3960162. PMID 24647078.

- G. F. Funston & P. J. Currie (2020) New material of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria) from the Campanian Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada, Historical Biology, doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1726908

- Cracraft, J (1971). "Caenagnathiformes: Cretaceous birds convergent in jaw mechanism to dicynodont reptiles". Journal of Paleontology. 45: 805–809.

- Sues, H.D. (1997). "On Chirostenotes, a Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Western North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 698–716. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011018.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)