Confuciusornithidae

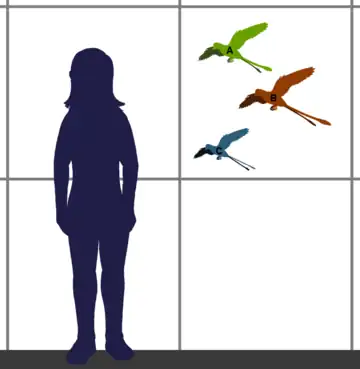

Confuciusornithidae is an extinct family of pygostylian avialans known from the Early Cretaceous, found in northern China. They are commonly placed as a sister group to Ornithothoraces, a group that contains all extant birds along with their closest extinct relatives. Confuciusornithidae contains four genera, possessing both shafted and non-shafted (downy) feathers. They are also noted for their distinctive pair of ribbon-like tail feathers of disputed function.

| Confuciusornithids Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Fossil specimen of Confuciusornis sanctus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Clade: | Pygostylia |

| Clade: | †Confuciusornithiformes Hou et al., 1995 |

| Family: | †Confuciusornithidae Hou et al., 1995 |

| Type species | |

| †Confuciusornis sanctus Hou et al., 1995 | |

| Genera | |

The wing anatomy of confuciusornithids suggests an unusual flight behavior, due to anatomy that implies conflicting abilities. They possessed feathers similar to those of fast-flapping birds, which rely on quick flapping of their wings to stay aloft. At the same time, their wing anatomy also suggests a lack of flapping ability. Confuciusornithids are also noted for their beak and lack of teeth, similar to modern birds. Both predators and prey, confuciusornithid fossils have been observed with fish remains in their digestive systems and have themselves been found in the abdominal cavities of Sinocalliopteryx, a compsognathid predator.

Classification

| Avialae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Confuciusornithidae was first named by Hou et al. in 1995 to contain the type genus, Confuciusornis, and assigned to the monotypic clade Confuciusornithiformes within the class Aves.[1] The group was given a phylogenetic definition by Chiappe, in 1999, who defined a node-based clade Confuciusornithidae to include only Changchengornis and Confuciusornis.[2]

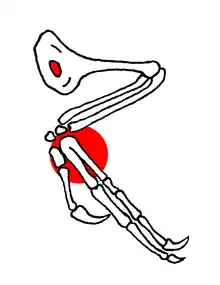

There are a number of features that define the clade. The most significant is the presence of a toothless jaw, which shows a more birdlike adaptation compared to Archaeopteryx. The other defining features are as follows, according to Chiappe et al. (1999):[2]

- There is a fork in the rostral (front) part of the mandibular symphysis, the area where the mandibles fuse together.

- The presence of a distinct maxillary fenestra (breathing hole) in the maxilla's ascending ramus.

- The deltopectoral crest of the humerus is prominent, which allows for increased muscle attachment for adductor muscles.

- The first metacarpal is not attached by bone to the other co-ossified metacarpals.

- The claw of the second manual digit is much smaller than the other claws.

- A V-shape in the sternum in the caudal end.

- The proximal phalanx of the third digit is much smaller than the other phalanges.

Confuciusornithidae is the most basal group of the clade Pygostylia, whose members possess a pygostyle, a fused set of caudal vertebrae at the end of the tail. The pygostyle replaced the longer, unfused tail found in more primitive avialans such as Archaeopteryx,[2] and may have served to improve flight. Pygostylia includes all modern birds, the only living members of the clade.

Additional members have been added to Confuciusornitidae since 1999. Jinzhouornis was added by Hou, Zhou, and Zhang in 2002,[3] and in 2008, Zhang, Zhou and Benton assigned the newly described genus Eoconfuciusornis to the family.[4]

Biogeography

Most confuciusornithids are known from the upper Jehol group, the Yixian Formation and Jiufotang Formation, dating from 125 to 120 million years ago. Eoconfuciusornis, however, predated the other confuciusornithids by 6 million years, dating to 131 Ma ago.

Anatomy

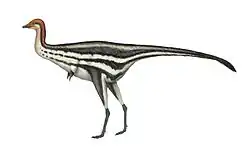

The entire body of confuciusornithids was covered in contour feathers, except for the foot, base of beak, and the tarsometatarsus, the bone directly attached to the foot.[5] It appears that they may also have had down feathers.[5]

The beaks of confuciusornithids show development of modern birdlike characteristics, such as a large beak and lack of teeth. The premaxilla and dentary are larger than those of Archaeopteryx.[6] The anterior of these bones shows evidence of vasculature and innervation, implying the presence of a beak.[2] The lack of recovery of this structure indicates that the beak had a soft horny sheath. The softness of the beak along with the innervation suggest that the beak was sensitive, making it useful for searching for prey.[5]

Much of their anatomy resembles that of Archaeopteryx, especially the pectoral girdle and forelimbs.[6] They were better adapted for flight than Archaeopteryx, due to the elimination of two thoracic vertebrae.[6] The development of a pygostyle also shows better adaptation for flight, as this replaces the long tails present in earlier avialans.[2] Similarly to Archaeopteryx, confuciusornithids possessed a large first digit with a hook-like claw. The digit implies a climbing lifestyle, as it serves to allow for hooking onto the grooves of trees. A similar anatomy and function is seen in the nestlings of the hoatzin, an extant South American bird.

The biomechanics of the wing itself are quite contentious due to a combination of traits that imply different modes of flight.[7] Confuciusornithids possessed long primary feathers similar to those of modern fast-flapping birds, as opposed to gliding birds which have short primaries relative to their size.[7] However, the narrowness of the wings of confuciusornithids along with the lack of upstroke ability during flapping motion seem to preclude the ability to flap their wings quickly.[7] Thus, they may have relied upon a flight method that no longer exists in modern birds.

The hindlimbs of confuciusornithids did not resemble those of living birds.[5] They were bad runners, with feet curved in a way that implies they did not move on the ground.

The long feathers of the tail (central rectrices) of confuciusornithids are of disputed function. Sexual dimorphism is an explanation, with males presumed to use the feathers in mating displays.[8] However, it has been argued that the long rectrices were instead used as a defense against predators, as many birds shed feathers to protect themselves. The observation that less than 10% of confuciusornithid fossils possess these feathers supports this, as they may have been shed either in response to predators, or to the stress of the sudden death that produced the fossils.[8]

Paleoecology

Confuciusornithids were first thought to be herbivorous due to the lack of teeth.[5] However, their anatomy was not adapted for plant consumption, as gastroliths have never been found, nor did the weak rhamphotheca of the beak allow for grinding. Instead, the beak appears to have been sensitive enough to assist in food acquisition and capable of holding potential prey. This beak type is well suited for skimming prey off of the top of a body of water.[5] Large numbers of fossils appear to originate from the tops of freshwater lakes, further supporting the water feeding connection. The remains of fish have been found in fossils of C. sanctus.[9] Confuciusornithids appear to have been unable to take off from water and lacked the adaptations necessary to live aquatically.[5] Thus, it appears that they flew along the surface of the water, using their beak to search for fish.

Confuciusornithid remains have been found in the abdominal contents of Sinocalliopteryx gigas, a compsognathid predator.[10] Multiple confuciusornithids were present in the remains, implying that they were all captured in a short time.[10]

Confuciusornithids appear to have been social animals, as concurrently buried fossils are often found in close proximity.[5]

Reproduction

A 2018 study suggests that confuciusornithids could not have incubated their eggs like modern birds do.[11] Other paravians (including Deinonychus) and pterosaurs are known to be superprecocial and able to fly soon after birth,[12][13][14] but for now there are no unambiguous confuciusornithid juveniles to attest this.

References

- Hou, L; Zhou, Z; Gu, Y; Zhang, H (1995). "Description of Confuciusornis sanctus". Chinese Science Bulletin. 10: 61–63.

- Chiappe, Luis M. et al. (1999)

- Hou, L. H.; Zhou, Zhouhe; Zhang, Fucheng; Gu, Yucai (2002). "Mesozoic birds from western Liaoning in China". Liaoning Science Cretaceous of China with Information from Two New Species.

- Zhang, FuCheng; Zhou, ZhongHe; Benton, Michael J. (2008-05-01). "A primitive confuciusornithid bird from China and its implications for early avian flight". Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences. 51 (5): 625–639. Bibcode:2008ScChD..51..625Z. doi:10.1007/s11430-008-0050-3. ISSN 1006-9313. S2CID 84157320.

- Zinoviev, A. V. (2009-07-01). "An attempt to reconstruct the lifestyle of confuciusornithids (Aves, Confuciusornithiformes)". Paleontological Journal. 43 (4): 444–452. doi:10.1134/S0031030109040145. ISSN 0031-0301. S2CID 85359766.

- Martin, L. D.; Zhou, Z.; Hou, L.; Feduccia, A. (1998-06-01). "Confuciusornis sanctus Compared to Archaeopteryx lithographica". Naturwissenschaften. 85 (6): 286–289. Bibcode:1998NW.....85..286M. doi:10.1007/s001140050501. ISSN 0028-1042. S2CID 10934480.

- Wang, X; Nudds, R. L.; Dyke, G. J. (2011). "The primary feather lengths of early birds with respect to avian wing shape evolution". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (6): 1226–1231. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02253.x. PMID 21418115.

- Peters, Winfried S.; Peters, Dieter Stefan (2009-12-23). "Life history, sexual dimorphism and 'ornamental' feathers in the mesozoic bird Confuciusornis sanctus". Biology Letters. 5 (6): 817–820. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0574. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2828012. PMID 19776067.

- Dalsätt, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ericson, P. G. P. (2006-09-01). "Food remains in Confuciusornis sanctus suggest a fish diet". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (9): 444–6. Bibcode:2006NW.....93..444D. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0125-y. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 16741705. S2CID 14377499.

- Xing, Lida; Bell, Phil R.; Iv, W. Scott Persons; Ji, Shuan; Miyashita, Tetsuto; Burns, Michael E.; Ji, Qiang; Currie, Philip J. (2012-08-29). "Abdominal Contents from Two Large Early Cretaceous Compsognathids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) Demonstrate Feeding on Confuciusornithids and Dromaeosaurids". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e44012. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744012X. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044012. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3430630. PMID 22952855.

- Deeming, D. C.; Mayr, G. (2018). "Pelvis morphology suggests that early Mesozoic birds were too heavy to contact incubate their eggs" (PDF). Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 31 (5): 701–709. doi:10.1111/jeb.13256. PMID 29485191. S2CID 3588317.

- Fernández, Mariela S.; García, Rodolfo A.; Fiorelli, Lucas; Scolaro, Alejandro; Salvador, Rodrigo B.; Cotaro, Carlos N.; Kaiser, Gary W.; Dyke, Gareth J. (2013). "A Large Accumulation of Avian Eggs from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina) Reveals a Novel Nesting Strategy in Mesozoic Birds". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e61030. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...861030F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061030. PMC 3629076. PMID 23613776.

- Parsons, William L.; Parsons, Kristen M. (2015). "Morphological Variations within the Ontogeny of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae)". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0121476. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1021476P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121476. PMC 4398413. PMID 25875499.

- Grellet-Tinner, G; Wroe, S; Thompson, MB; Ji, Q (2007). "A note on pterosaur nesting behavior". Historical Biology. 19 (4): 273–7. doi:10.1080/08912960701189800. S2CID 85055204.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)