Spanish conquest of Nicaragua

The Spanish conquest of Nicaragua was the campaign undertaken by the Spanish conquistadores against the natives of the territory now incorporated into the modern Central American republic of Nicaragua during the colonisation of the Americas. Before European contact in the early 16th century, Nicaragua was inhabited by a number of indigenous peoples. In the west, these included Mesoamerican groups such as the Chorotega, the Nicarao, and the Subtiaba. Other groups included the Matagalpa and the Tacacho.

Gil González Dávila first entered what is now Nicaragua in 1522, with the permission of Pedrarias Dávila, governor of Castilla de Oro, but was driven back to his ships by the Chorotega. In 1524, a new expedition led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba founded the Spanish towns of León and Granada. The western portions of Nicaragua along the Pacific littoral plain received the brunt of the Spanish activity in the territory for the next three decades.[1] Within a century of the conquest, the native inhabitants had been all but eliminated due to war, disease, and exportation as slaves.

Geography

Nicaragua is the largest country in Central America, covering an area of 129,494 square kilometres (49,998 sq mi) – or 120,254 km2 (46,430 sq mi) without including the surface area of its two largest lakes. The country is bordered to the north by Honduras, and to the south by Costa Rica; it is bordered to the west by the Pacific Ocean and to the east by the Caribbean Sea.[2] Nicaragua is divided into three broad regions, the Pacific Lowlands in the west, the Central Highlands, and the Caribbean Lowlands in the east.[3] The Pacific lowlands are largely a coastal plain extending approximately 75 km (47 mi) inland from the Pacific Ocean. A chain of volcanoes extends from the Gulf of Fonseca southeast towards Lake Nicaragua; many of them are active. The volcanoes lie along the western edge of a rift valley running southeast from the Gulf of Fonseca to the San Juan River, which forms a part of the border with Costa Rica. The two largest lakes in Central America dominate the rift valley: Lake Managua and Lake Nicaragua. Lake Managua measures 56 by 24 km (35 by 15 mi), and Lake Nicaragua measures 160 by 75 km (99 by 47 mi). The Tipitapa River flows south out of Lake Managua and into Lake Nicaragua, which empties into the Caribbean via the San Juan River.[2] The Central Highlands reach altitudes of up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) above mean sea level, and consist of generally east–west running ranges that include the Cordillera Dariense, Cordillera de Dipilto, Cordillera Isabella, the Huapí Mountains, and the Yolaina Mountains.[4]

Climate

In central Nicaragua, the temperature varies between 20 and 25 °C (68 and 77 °F); rainfall averages 1,000 to 2,000 mm (39 to 79 in) per year. There is a four-month dry season, with the rain season lasting throughout the rest of the year. Before the conquest, the Central Highlands were covered with coniferous forest.[4] The Pacific coastal plain is classified as tropical dry forest, and features fertile volcanic soils. The Atlantic lowlands receive higher rainfall; the soils are less fertile, and the region is classified as tropical moist forest.[5]

Nicaragua before the conquest

When the Spanish first arrived in what is now Nicaragua there were three principal indigenous groups living in the western portions of the country; these were the Chorotega (also known as the Mangue),[6] the Nicarao, and the Matagalpa (also known as Chontal, from the Nahuatl term for "foreigner").[7] The Nicarao were a Nawat-speaking Mesoamerican people that had migrated southwards from central Mexico from the 8th century AD onwards. They broke off from the Pipil around the early 13th century and settled in pockets of western Nicaragua along the Pacific coast, with their heaviest concentration in what is now the department of Rivas.[8] The Chorotega were also a Mesoamerican people that had migrated from Mexico and spoke the Mangue language. The Subtiaba (also known as the Maribio) were another group of Mexican origin, speaking the Subtiaba language. The Tacacho were a small group of unknown origin and language.[6] The Matagalpa were a non-Mesoamerican people of the Intermediate Area, who spoke a Misumalpan language, but belonged to the Chibchoidean cultural region.[9] They occupied the Central Highlands,[4] over an area covering the modern departments of Boaco, Chontales, Estelí, Jinotega, Matagalpa, southwestern parts of Nueva Segovia, and neighbouring parts of Honduras.[10] The Matagalpa were a tribal society organised into different lineages and chiefdoms, who engaged in organised intertribal warfare; at the time of Spanish contact they were at war with the Nicarao.[11] Eastern Nicaragua was inhabited by Chibchoidean peoples such as the Rama, and the Misumalpa peoples such as the Mayangna and the Miskito.[12] The Chibchoidean peoples of the interior were culturally related to South American groups, and had developed more complex societies than that of the Miskito, who were of Caribbean origin.[13]

The population of Nicaragua at the time of contact is estimated at 825,000. The first century after Spanish contact witnessed the demographic collapse of the native populations, resulting principally from exposure to Old World diseases and their exportation as slaves, but also from a combination of war and mistreatment.[14]

Native weapons and tactics

The Spanish described the Matagalpa as being well-organised, with ordered battle-lines. The Nicarao engaged in war with the Matagalpa, probably in order to capture slaves, and prisoners to be offered for human sacrifice.[11]

Background to the conquest

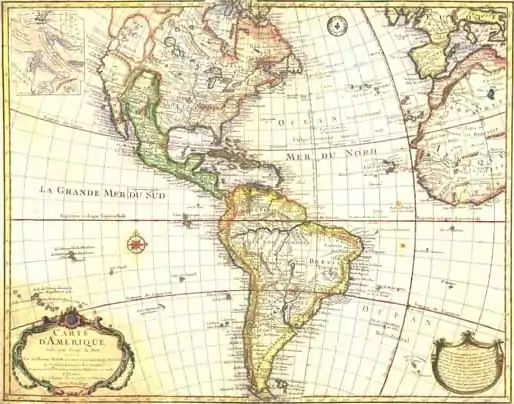

Christopher Columbus discovered the New World for the Kingdom of Castile and Leon in 1492. Private adventurers thereafter entered into contracts with the Spanish Crown to conquer the newly discovered lands in return for tax revenues and the power to rule.[15] The Spanish founded Santo Domingo on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in the 1490s.[16] In the first decades after the discovery of the new lands, the Spanish colonised the Caribbean and established a centre of operations on the island of Cuba.[17]

In the first two decades of the 16th century, the Spanish established their domination over the islands of the Caribbean Sea, and used these as a staging point to launch their campaigns of conquest on the continental mainland of the Americas.[18] From Hispaniola, the Spanish launched expeditions and campaigns of conquest, reaching Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, Cuba in 1511, and Florida in 1513.[19]

In the south, the Spanish established themselves in Castilla de Oro (modern Panama),[20] when Vasco Núñez de Balboa founded Santa María la Antigua in 1511. In 1513, while exploring westwards, Balboa discovered the Pacific Ocean, and in 1519 Pedrarias Dávila founded Panama City on the Pacific coast.[21] The focus soon turned to exploring south along the Pacific coast towards South America.[22]

The Spanish heard rumours of the rich empire of the Aztecs on the mainland to the west of their Caribbean island settlements and, in 1519, Hernán Cortés set sail to explore the Mexican coast.[17] By August 1521 the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had fallen to the Spanish.[23] The Spanish conquered a large part of Mexico within three years, extending as far south as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The newly conquered territory became New Spain, headed by a viceroy who answered to the Spanish Crown via the Council of the Indies.[24]

The discovery of the Aztec Empire and its great riches changed the focus of exploration out of Panama from the south to northwest.[22] Various expeditions were then launched northwards involving notable conquistadors such as Pedrarias Dávila, Gil González Dávila, and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (not to be confused with the conquistador of the same name involved in the Spanish conquest of Yucatán).[20]

Conquistadors

The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.[25] Many of the Spanish were already experienced soldiers who had previously campaigned in Europe.[26] Pedrarias Dávila was a nobleman whose father and grandfather had been influential in the courts of the kings John II and Henry IV of Castile.[27] Gabriel de Rojas was an officer of Dávila who probably travelled from Spain with him; he was a younger brother drawn from a notable family that had risen to prominence in the service of Henry IV of Castile,[28] and was a veteran of the conquest of Tierra Firme (Caribbean South America). After campaigning in Nicaragua he distinguished himself in the conquest of Peru.[29] Little is known of the origin of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba; he was likely to have been a commoner elevated to the nobility as a result of his actions in the New World.[30] Gil González Dávila was a professional soldier who arrived in Panama in 1519.[31] Hernando de Soto was a nobleman from Villanueva de Barcarrota. After Nicaragua, he campaigned in Peru, served as governor of Cuba, and explored Florida.[32] Pedro de Garro was a veteran of the Italian Wars. He brought 43 cavalry and 57 infantry to support Gil González in Honduras, and soon passed to Nicaragua to assist Hernández de Córdoba.[33]

Spanish weapons and armour

The 16th-century Spanish conquistadors were armed with broadswords, rapiers, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery. Mounted conquistadors were armed with a 3.7-metre (12 ft) lance, that also served as a pike for infantrymen. A variety of halberds and bills were also employed. As well as the one-handed broadsword, a 1.7-metre (5+1⁄2 ft) long two-handed version was also used.[34] Crossbows had 60-centimetre (2 ft) arms stiffened with hardwoods, horn, bone and cane, and supplied with a stirrup to facilitate drawing the string with a crank and pulley.[35] Crossbows were easier to maintain than matchlocks, especially in the humid tropical climate of the Caribbean region.[36]

Metal armour was of limited use in the hot, wet tropical climate. It was heavy and had to be constantly cleaned to prevent rusting; in direct sunlight, metal armour became unbearably hot. Conquistadores often went without metal armour, or only donned it immediately prior to battle.[37] They were quick to adopt quilted cotton armour based upon that used by their native opponents, and commonly combined this with the use of a simple metal war hat.[38] Shields were considered essential by both infantry and cavalry; generally this was a circular target shield, convex in form and fashioned from iron or wood. Rings secured it to the arm and hand.[34]

Role of the Church

The justification for conquest was explicitly religious. In 1493, the Spanish Pope Alexander VI issued the Bulls of Donation that justified the colonisation of the New World for the express purpose of converting the native inhabitants to Christianity.[39] The Spanish Crown and the Church insisted that the conquered peoples were human souls meriting legal rights and protection, while some colonists claimed they were subhuman, and a valid resource for forced labour. These opposing viewpoints led to conflict between the authorities in Spain and the colonists on the ground in the Americas.[40] There was religious participation in the conquest of Nicaragua from the first exploratory expeditions onwards; Father Diego de Agüero accompanied Gil González on his 1519 expedition, and returned with Francisco Hernández de Córdoba in 1524, with two religious companions.[41] One of the first actions performed upon entering an indigenous settlement was to plant a cross on top of the local shrine, to symbolically replace the native religion with the authority of the Church.[42] Fathers Contreras and Blas Hernández established the first Jesuit presence in 1619.[43]

Discovery of Nicaragua, 1519–1523

Spanish explorers first viewed the Pacific coast of Nicaragua in 1519, sailing up from Panama.[44] That year, Pedrarias Dávila executed Vasco Núñez de Balboa and seized his ships on the Pacific coast of Panama. He put Gaspar de Espinosa in command of two ships, San Cristóbal and Santa María de la Buena Esperanza, and sent him to scout westwards.[45] Espinosa disembarked at the Burica Peninsula, on the modern border between Panama and Costa Rica, to return overland to Panama.[46] The two ships continued along the coast, under the command of Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León.[47] They discovered the Gulf of Nicoya, probably on 18 October of that year, which became the key entry route to Nicaragua for later expeditions.[48] This first tentative expedition made landfall at the Gulf of Nicoya, but did not establish a Spanish presence;[44] they were met by a great number of native canoes carrying warriors, with more warriors amassed on the shore making a great display of force. Seeing that there would be fierce opposition, the ships turned back to Panama. The Spanish managed to capture three or four natives, who were taken back with them to learn Spanish and be used as interpreters.[49]

Departure of Andrés Niño and Gil González Dávila

The Spanish Crown issued a license to explore the Pacific coast to Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño in Zaragoza in October 1518;[50] they set out from Spain in September 1519.[51] Although the Crown had issued them permission to use Balboa's two ships still anchored on the Pacific coast of Panama, Pedrarias Dávila opposed their taking possession, arguing that they were not Balboa's exclusive property. González Dávila and Niño therefore built their own ships on the Pearl Islands.[52] On 21 January 1522,[53] with the approval of Pedrarias Dávila, who was governor of Castilla de Oro (modern Panama), they travelled northwest across Costa Rica and the Isthmus of Rivas into southwestern Nicaragua.[54] The expedition advanced slowly westwards, only reaching southeastern Costa Rica in October or November 1522.[53] Due to damage sustained by their ships, and spoiled water, they decided to split up.[53] Andrés Niño repaired the ships and scouted the coast,[55] while Gil González penetrated inland with 100 Spaniards and 400 native auxiliaries.[56] They met up at the Gulf of Nicoya, where Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León had made landfall,[53] at what is now the port of Caldera, in Costa Rica. Here they noticed that the natives had cultural traits more in common with the inhabitants of the Yucatán Peninsula. By this time, González was weakened by sickness, and wished to continue by sea, but his men demanded he continue the march with them.[57] They used one of the ships to cross to the western shore of the Gulf of Nicoya, where they were received enthusiastically by the natives.[58] He pushed on overland, with 100 Spaniards and 4 horses.[57]

Exploration of the Pacific coast

While Gil González Dávila marched overland with his troops, Andrés Niño left two of his ships behind and sailed onwards with the remaining two.[59] On 27 February 1523, Niño put to shore at El Realejo, where Captain Antón Mayor formally took possession of the territory in the name of the Spanish crown, the first Spanish act in the territory of what is now Nicaragua.[48] They met no opposition at that time, and the act was officially recorded by Juan de Almanza, who acted as scribe for the legal documentation. To commemorate this act, they named the place Posesión. Niño sailed onwards, making landfall on an island in the Gulf of Fonseca on 5 March, giving the gulf its name in honour of Spanish bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca.[59] Niño continued onwards as far as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in what is now Mexico.[58]

Expedition inland

Meanwhile, on his march inland, Gil González heard rumours of a powerful native ruler called Nicarao, who commanded many warriors. He was advised not to continue, but decided to march on until he met opposition.[60] Nicarao intercepted Gil González outside his capital city,[61] called Quauhcapolca,[62] and received him in peace. He invited the Spaniards to lodge near the city plaza and the two leaders exchanged gifts; González wrote that he received the equivalent of 15,000 gold castellanos. The Spanish captain gifted Nicarao with silk clothing and many other items brought from Spain. Over the course of the next few days, the Spanish instructed the natives in the basics of Christian religion. He claimed that after this, the natives wished to convert to the new religion, and that just over 9,000 people were baptised in one day, including adults and children of both genders.[61] After several days in the Nicarao capital, González learned of Lake Nicaragua, and he sent a small detachment of soldiers to confirm its existence; he then travelled in person with 15 foot soldiers and 3 mounted soldiers. Among those who went with him to the lakeshore were the expedition's treasurer Andrés de Cereceda, and friar Diego de Agüero.[63] On 12 April 1523 they claimed the lake for the Spanish Crown under the name of Mar Dulce ("sweet sea").[64] González sent out a canoe to scout the lake for a short distance, and questioned the natives as to whether it connected with the sea, without receiving any clear response; nonetheless, the Spanish were convinced that the lake must have an outlet to the Caribbean Sea, and that they had discovered a new route across the Central American isthmus.[65] A great many natives came to see the newly arrived Europeans, driven by curiosity about their strange appearance and mode of dress, and horses, which the natives had never seen before.[66]

Opposition and retreat

From Quauhcapolca, Gil González Dávila advanced to the indigenous settlement of Coatega,[66] near the Mombacho volcano,[67] where he was met by another powerful ruler, Diriangén, leader of the Chorotega.[68] Diriangén came accompanied by a great many richly adorned followers, and said he had come to the bearded strangers and their animals for himself.[69] After the initial encounter, Diriangén said he would return in three days. He returned on 17 April at midday, arrayed for battle. The Spanish were alerted to the surprise attack by one of the local natives; even so a violent struggle ensued that resulted in the wounding of various Spanish defenders. The use of their small number of horses assisted them, since they struck fear into the enemy. The Chorotega attack was beaten off, and González immediately sent messengers to call back an advance party consisting of friar Agüero accompanied by a number of soldiers, who had been advancing towards Diriangén's territory. The violent opposition of the Chorotega convinced González and his officers to turn back with the gold they had already collected.[70] They marched back south through Nicarao territory, by now suspicious of all indigenous activity. They took up a defensive formation, in a compact group with a single mounted soldier on each side. In the main group, 60 of the fittest soldiers went ready for battle, while the wounded travelled with the supplies, gold, and native porters in the centre.[67] They were met with passively hostile reactions from the natives they passed, until they finally met a number of Nicarao nobles, who apologised for the hostile reception.[71] González accepted the apology, due to the vulnerability of his forces. They spent the next night in a state of alert upon a hilltop; the next day they continued their retreat in defensive formation, crossing lands abandoned by the Indians until they reached the safety of their ships on the Pacific coast. Andrés Niño had returned to the anchorage a few days previously, but all the ships were in poor repair and the Spanish expedition was forced to make the arduous journey back to Panama in canoes. They arrived back at Panama on 23 June 1523.[72]

Gil González Dávila had discovered Lake Nicaragua, met Nicarao, and converted thousands of natives to the Roman Catholic religion.[73] These included the 9,000 vassals of Nicarao, and 6,000 of Nicoya; González claimed that the total number of natives baptised by the expedition was 32,000.[74] The overland expedition had collected a significant quantity of gold from the natives,[75] amounting to 112,525 gold pesos, including that which had been collected while crossing Costa Rica.[76]

Rival plans, 1523

Gil González Dávila planned to return to Nicaragua as soon as possible,[72] but faced interference from Pedrarias Dávila and from Panama City's treasurer, Alonso de la Puente.[77] Pedrarias Dávila had learned of their discovery of gold and acted quickly to outfit a new expedition in late 1523. While the two explorers put in a claim to the Spanish Crown of the lands they had discovered, he planned to seize control of the newly discovered territories before the Crown could validate González and Niño's claims. The new expedition was a private enterprise under royal commission; the participants signed the two-year contract on 22 September 1523, with one third of the spoils to go to Pedrarias Dávila, and one sixth each to auditor Diego Marquez, treasurer Alonso de la Puente, lawyer Juan Rodríguez de Alarconcillo, and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba. Hernández de Córdoba was placed in command.[78] Pedrarias Dávila sent one of his captains to Spain to recruit more men, and purchase horses,[79] while in Panama he purchased Andrés Niño's ships, rigging, horses, and other items for 2,000 gold pesos.[80] Meanwhile, González planned to return to Nicaragua by exploring a river route from the Caribbean Sea to Lake Nicaragua, thus avoiding Pedrarias Dávila's jurisdiction over Castilla de Oro completely.[81] In the event, he landed further west and initiated the Spanish conquest of Honduras.[82] Although González expedition was the first to set foot in Nicaragua, Pedrarias Dávila based his own claim upon the earlier discovery of the territory by Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León, under his orders.[83]

Hernández de Córdoba in western Nicaragua, 1523–1525

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, under orders of Pedrarias Dávila, set out from Panama for Nicaragua in mid-October 1523, probably on 15 October.[84] The expedition consisted of three or four ships, carrying over 200 men, including officers, foot soldiers, cavalry, and approximately 16 African slaves.[85] His senior officers were Antón Mayor, Juan Alonso Palomino, Alonso de Peralta, Francisco de la Puente, Gabriel de Rojas, and Hernando de Soto.[29]

In 1524, Hernández founded the colonial towns of León and Granada.[73] He founded Granada by the indigenous town of Jalteba, and León in the centre of the native province of Imabite.[86] There are no direct accounts of the expedition that founded these first Spanish towns; such accounts would have taken the form of letters sent to Pedrarias Dávila in Panama, where they were lost.[87] It is known that the natives put up some resistance, but not how many battles were fought, nor where, nor who led indigenous resistance against the Spanish. Hernández is likely to have followed Gil González Dávila's route from the Gulf of Nicoya to the territory of the Nicarao.[88] The expedition carried parts for a small brigantine, which the Spanish assembled on the shores of Lake Nicaragua.[89] The brigantine explored the lake, and found that it did indeed flow out to the Caribbean via a river, but that the river was too rocky to be navigable, with several waterfalls blocking progress. Nonetheless, the explorers were able to confirm the river's course, and that the land was heavily populated by indigenous groups, and that the terrain was forested. The party sent by Hernández continued overland for 80 leagues (approximately 335 km or 208 mi)[nb 1] before turning back.[41]

Hernández divided his forces into three groups; one division remained under his direct command, one placed under the command of Hernando de Soto, and the other under the command of Francisco de la Puente.[33] By 1 May 1524, Hernández had advanced as far west as Tezoatega (now known as El Viejo, in the department of Chinandega).[91] Around this time, the natives of the Cordillera de los Maribios mountains, about 5 leagues from León (about 21 km or 13 mi), killed a large number of indigenous men and women, dressed themselves in their skins and met the Spanish in battle, but were routed.[92] By the beginning of August, Hernández was in the vicinity of León, passing through the native provinces of Imabite and Diriondo. It is likely that León was not actually founded until after this,[93] but before April 1525, when Hernández sent a letter to Pedrarias Dávila, having already founded León and Granada.[94] Undocumented indigenous resistance is supported by Spanish records showing that as early as 1524, prisoners of war were being shipped to Panama as slaves.[95]

Dispute with Honduras, 1524–1525

While establishing a Spanish presence in Nicaragua, Hernández de Córdoba received news of a new Spanish presence to the north.[96] Gil González Dávila had arrived in the Olancho Valley (within the modern borders of Honduras).[97] The jurisdictional limits of Nicaragua had not yet been set, and Gil González viewed himself as the rightful governor of the territory.[98] Hernández sent Gabriel de Rojas to investigate, who was received in peace by González. González instructed Rojas that neither Pedrarias Dávila nor Hernández de Córdoba had any rights over Honduras, and that González would not permit them to take any action there. Rojas reported back to Hernández de Córdoba, who immediately dispatched soldiers under the command of Hernando de Soto to capture González.[97] González caught Hernando de Soto by surprise with a night-time assault, and a number of de Soto's men were killed in the fighting that followed. González succeeded in capturing de Soto, along with 130,000 pesos. Although he had won the day, González was aware that Hernández de Córdoba was unlikely to let matters rest, and he also received news that a new Spanish expedition had arrived on the north coast of Honduras. Not wishing to be surrounded by hostile Spanish rivals, González set de Soto free and rushed north.[99] As events played out in Honduras, and Gil González lost the initiative, some of his men deserted and marched south to join the forces of Hernández de Córdoba in Nicaragua.[100]

Gabriel de Rojas remained in Olancho into 1525 in a continued attempt to extend Nicaraguan jurisdiction there;[101] he was told by native informants of new Spanish arrivals in Honduras,[102] where, in September,[103] Hernan Cortés, conqueror of Mexico, had arrived to impose his authority. Rojas sent a letter and gifts with messengers, who met Gonzalo de Sandoval, then proceeded onwards to Cortés at Trujillo. Cortés at first responded in a friendly manner to Rojas' overtures.[102] Upon meeting native resistance, Rojas' men began pillaging the district and enslaving the inhabitants.[101] Cortés dispatched Sandoval to order Rojas out of the territory, and to release any Indians and their goods that he had seized. Sandoval was under orders to either capture Rojas, or expel him from Honduras, but in the event was unable to do either.[102] While the two groups were still gathered, Rojas received orders from Hernández de Córdoba to return to Nicaragua to assist him against his rebellious captains.[104]

Hernández de Córdoba sent a second expedition into Honduras, carrying letters to the Audiencia of Santo Domingo and to the Crown, searching for a good location for a port on the Caribbean coast, to provide a link to Nicaragua. The expedition was intercepted and captured by Sandoval, who sent some of the Nicaraguan party back to Cortés at Trujillo.[101] They informed Cortés of a plan by Hernández de Córdoba to set himself up in Nicaragua independently of Pedrarias Dávila in Panama.[105] Cortés responded courteously and offered supplies while the expedition was passing through Honduras, but sent letters advising Hernández de Córdoba to remain loyal to Pedrarias Dávila.[106]

Hernández was able to collect a substantial amount of gold in Nicaragua, collecting more than 100,000 pesos of gold in a single expedition; this was consequently seized by Pedrarias Dávila.[107] In May 1524, Hernández sent a brigantine back to Panama with the Royal fifth, which amounted to 185,000 gold pesos.[108] By 1525, Spanish power had been consolidated in western Nicaragua, and reinforcements had arrived from Natá, in Panama, which had become a key port of call for shipping between Nicaragua and Panama.[109]

Intrigue in Nicaragua, late 1525

The friendly contacts between Hernán Cortés and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba were viewed with deep suspicion by those in León who remained loyal to Pedrarias Dávila, such as Hernando de Soto, Francisco de Compañón, and Andrés de Garabito. These officers may also have been motivated by ambition to view Hernández de Córdoba's contact with Cortés as treachery against Pedrarias Dávila.[110] Hernández de Córdoba's position in Nicaragua was consolidated by his foundation of three colonial towns there, although his contract for conquest specifically limited his license to two years from the day he sailed from Panama. Hernández de Córdoba's growing claim over the territory may also have caused Pedrarias Dávila to view his contacts with Cortés with deep suspicion, and a threat to Dávila's own claim.[111]

Rumours, encouraged by Hernández de Córdoba's enemies, spread quickly in the colony that he was plotting with Cortés.[112] About a dozen supporters of Hernando de Soto and Francisco de Compañón secretly plotted against Hernández de Córdoba; he responded by seizing de Soto and imprisoning him in Granada.[113] De Soto and de Compañón fled Nicaragua with several companions, and took word to Pedrarias Dávila in Panama, arriving there in January 1526.[114]

Pedrarias Dávila in western Nicaragua, 1526–1529

Pedrarias Dávila set out from Nata by sea with soldiers and artillery, and landed on the island of Chira, in the Gulf of Nicoya, opposite the colonial settlement of Bruselas on the mainland (then within the jurisdiction of Nicaragua, but now in Costa Rica). There he established a base of operations, and the indigenous inhabitants received him in peace; from these Dávila learned that Hernández de Córdoba had evacuated Bruselas a few days previously.[114] Dávila waited in Chira for reinforcements led by Hernando de Soto, who marched overland from Panama with two units of infantry and cavalry.[115] Dávila subsequently arrested his wayward lieutenant Hernández de Córdoba and ordered his execution.[73]

In 1526, Pedrarias Dávila was replaced as governor of Castilla del Oro; Diego López de Salcedo, governor of Honduras, took advantage of the change in leadership to extend his jurisdiction to include Nicaragua. He marched to Nicaragua with 150 men to impose his authority. He arrived in León in spring of 1527, and was accepted as governor by Martín de Estete, Pedraria Dávila's lieutenant there. His poor government soured relations with the colonists, and provoked the restless natives of northern Nicaragua into open revolt against Spanish authority.[116] Pedro de los Ríos, the new governor in Panama, moved into Nicaragua to challenge López de Salcedo, but was rejected by the colonists and was ordered back to Panama by the governor of Honduras.[117] Meanwhile, Dávila had vociferously protested to the Spanish crown over his loss of governorship of Castilla del Oro, and in recompense was given the governorship of Nicaragua. López de Salcedo prepared to retreat back to Honduras, but was prevented by Martín de Estete and the Nicaraguan colonists, who now pledged their allegiance to Pedrarias Dávila. López de Salcedo's officials were arrested.[118]

León became the capital of the Nicaraguan colony, and Dávila transferred there as governor of the province in 1527.[73] He arrived in León in March 1528, and was accepted everywhere as the rightful governor. He immediately imprisoned López de Salcedo and held him for almost a year, refusing to allow him to return to Honduras. Eventually his release was negotiated by intermediaries, and he renounced all claims to territory beyond a line from Cape Gracias a Dios to León and the Gulf of Fonseca. López de Salcedo returned to Honduras as a broken man early in 1529. This agreement settled the jurisdictional disputes between Nicaragua and Honduras.[118]

Pedrarias Dávila introduced European farming methods and became infamous for his harsh treatment of the natives.[73] In 1528 to 1529, friar Francisco de Bobadilla of the Mercedarian Order was very active, and baptised over 50,000 natives among the Subtiaba, Diriá (a tribe of the Chorotega), and Nicarao.[86]

Central Highlands, 1530–1603

In 1530, an alliance of Matagalpa tribes launched a concerted attack against the Spanish, with the intention of burning the colonial settlements. In 1533, Pedrarias Dávila requested reinforcements to pursue the Matagalpa and punish their revolt, in order to discourage neighbouring peoples from allying with them against the Spanish.[11]

By 1543, Francisco de Castañeda founded Nueva Segovia in north-central Nicaragua, some 30 leagues from León.[119] By 1603, the Spanish had established their dominion over seventeen indigenous settlements in the north-central region that the Spanish named Segovia. The Spanish drafted warriors from these settlements to assist in putting down ongoing indigenous resistance in Olancho, in Honduras.[120]

Fringes of empire: Eastern Nicaragua

From relatively soon after European contact, the Atlantic coast of what is now Nicaragua fell under the influence of the English.[121] This region was inhabited by natives that remained beyond Spanish control, and was known to the Spanish as Tologalpa.[122] Tologalpa is poorly defined in colonial Spanish documentation; Tololgalpa and Taguzgalpa together comprised an extensive region stretching along the Caribbean coast eastwards from Trujillo, or the Aguan River, to the San Juan River, and as far back as the Chontalean Mountain Range (Cordillera de Chontales). Taguzgalpa was that part of the region that now falls within the modern borders of Honduras, and Tologalpa was that part that now falls within Nicaragua.[123] However, together they formed one single Province that was created by a Royal Order of February 10, 1576.[124] From the second half of the 17th century, both regions were together referred to as Mosquitia or Mosquito Coast.[124] Very little is known about the original inhabitants of Mosquitia, beyond that they included the Jicaque, Miskito, and Paya.[125]

In 1508, Diego de Nicuesa was given the governorship of the Governorate of Veragua, a region stretching along the Caribbean coast from the Belén River in Panama to Cape Gracias a Dios, on the current border between Nicaragua and Honduras.[126] In 1534, a license to conquer and colonise the region was issued to Felipe Gutiérrez y Toledo, governor of Veragua, who abandoned his plans to settle the area.[127] In 1545, governor of Guatemala Alonso de Maldonado wrote to the king of Spain, explaining that Taguzgalpa was still beyond Spanish control, and that its inhabitants were a threat to those Spanish living on the borders of the region. In 1562, a new license of conquest was issued to the governor of Honduras, Alonso Ortiz de Elgueta, who sent pilot Andrés Martín to scout the coast from Trujillo as far as the mouth of the San Juan River. Martín founded the settlement of Elgueta on the shore of Caratasca Lagoon (in Honduran Taguzgalpa), which was soon moved inland, to vanish from history. Around the same time, conquistador Juan Dávila launched several self-funded expeditions into the interior of Tologalpa, without success.[128]

In 1641 or 1652, a shipwrecked slave ship gave rise to the Miskito Sambu, when surviving Africans intermixed with the indigenous coastal groups. The Miskito Sambu developed strong ties to English colonists that settled in Jamaica from 1655 onwards, and with groups of English colonists that had settled along the Mosquito Coast. They became the dominant coastal group, allying or subjugating other groups in the region.[129]

When the Kingdom of Guatemala declared itself independent of Spain in 1821, most of Mosquitia was still outside of Spanish control.[126]

Legacy of the conquest

Within a century of the conquest, the Nicarao were effectively eliminated by a combination of the slave trade, disease, and warfare.[6] It is estimated that as many as half a million slaves were exported from Nicaragua before 1550, although some of these had originally come from other parts of Central America.[130] Although Gil González Dávila had initially recovered a significant amount of gold, Spanish hopes of extracting great quantities of gold from the province proved ephemeral.[131] Even when sources of gold were found, the collapse of native population levels meant that the Spanish were unable to work the mines. In 1533, the Spanish noted that although gold had been found in Santa María de la Buena Esperanza, about 25 leagues from León, a measles epidemic had killed so many natives that there were none left to extract the ore.[132] By the end of the 16th century, Nicaragua contained a relatively modest 500 Spanish colonists.[133]

Historical sources

Gil González Dávila wrote a number of letters in 1524 describing his discovery of Nicaragua, including a letter to 16th-century chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés containing his most complete account of his actions there.[134] Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés dedicated the entire 16-chapter Book IV of the Third Part of his Historia general de las Indias (General History of the Indies) to Nicaragua, which was published in Seville in 1535. He had himself lived in Nicaragua for a year and a half, from the very end of 1527 through to July 1529. His chronicle includes an account of the discovery of Nicaragua by Gil González Dávila.[135] Chronicler Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas described the first voyage of Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño in Chapter 5 of Book IV of his Historia General de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Oceáno (General History of the deeds of the Castilians in the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea).[48] Francisco Hernández de Córdoba's foundation of the colonial towns of León and Granada was described in a letter to the king of Spain, written by Pedrarias Dávila in 1525.[136] Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas included an account of the discovery of Nicaragua by Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León in his Historia de las Indias (History of the Indies).[137] Juan de Castañeda wrote his own account of his voyage of discovery, now contained in the national archives of Costa Rica;[138] it was written in 1522.[62]

See also

Footnotes

Citations

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 231.

- Merril 1993a.

- Newson 1982, p. 261.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 234.

- Salamanca 2012, p. 7.

- Fowler 1985, p. 38.

- Staten 2010, pp. 14–15. Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 233.

- Fowler 1985, pp. 37–38.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 242. Fonseca Zamora 1998, p. 36.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 229.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 236.

- Salamanca 2012, pp. 7, 12, 14.

- García Añoveros 1988, p. 49.

- Staten 2010, p. 15.

- Feldman 2000, p. xix.

- Nessler 2016, p. 4.

- Smith 1996, 2003, p. 272.

- Barahona 1991, p. 69.

- Deagan 1988, p. 199.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 10.

- Montoya 2015, p. 27.

- Solórazno Fonseca 1992, p. 315.

- Smith 1996, 2003, p. 276.

- Coe and Koontz 2002, p. 229.

- Polo Sifontes 1986, pp. 57–58.

- Polo Sifontes 1986, p. 62.

- Mena García 1992, p. 16.

- Velasco 1985, pp. 373–375.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 80.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 32–33.

- Olson et al. 1992, p. 283.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 81.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 82.

- Pohl and Hook 2008, p. 26.

- Pohl and Hook 2008, pp. 26–27.

- Pohl and Hook 2008, p. 27.

- Pohl and Hook 2008, p. 23.

- Pohl and Hook 2008, p. 16, 26.

- Deagan 2003, pp. 4–5.

- Deagan 2003, p. 5.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 78.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 78–79.

- Sariego 2005, p. 12.

- Stanislawski 1983, p. 1.

- Calvo Poyato 1988, p. 7.

- Calvo Poyato 1988, pp. 7–8.

- Calvo Poyato 1988, p. 8. Quirós Vargas and Bolaños Arquín 1989, p. 31.

- Calvo Poyato 1988, p. 8.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 49.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 50–51.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 51.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 52–53.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 53.

- Staten 2010, p. 16. Stanislawski 1983, p. 1. Meléndez 1976, p. 51.

- Stanislawski 1983, p. 1. Meléndez 1976, p. 53.

- Stanislawski 1983, p. 1. Solórzano Fonseca 1992, pp. 316–317.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 54.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 56.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 55.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 56–57.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 57.

- Healy 1980, 2006, p. 21.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 59.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 59–60.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 60–61.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 61.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 63.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 61. Staten 2010, p. 16.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 61–62.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 62.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 63–64.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 64.

- Staten 2010, p. 16.

- Newson 1982, p. 257. Stanislawski 1983, p. 1.

- Stanislawski 1983, p. 1. Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 239.

- Solórzano Fonseca 1992, pp. 316–317.

- Meléndez 1976 pp. 64–65.

- Stanislawski 1983, pp. 1–2. Meléndez 1976, p. 70.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 71.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 72.

- Meléndez 1976 p. 65.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 11. Sarmiento 1990, 2006, p. 17.

- Meléndez 1976 p. 68.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 75–76. Staten 2010, p. 16.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 76–77.

- Newson 1982, p. 257.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 75.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 77.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 77–78.

- Rowlett 2005.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 79–80.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 84–85.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 85–86.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 89.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 87–88.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, pp. 10–11.

- Sarmiento 1990, 2006, p. 18. Leonard 2011, p. 19.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 93.

- Sarmiento 1990, 2006, p. 19.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 98.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 18.

- Sarmiento 1990, 2006, p. 21.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 102.

- Sarmiento 1990, 2006, p. 22.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, pp. 18–19.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 19.

- Ibarra Rojas 2001, p. 95.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 83.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 90, 92.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 106-107.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 108.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 108. Staten 2010, p. 16.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 109.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 110.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 111.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 22.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, pp. 22–23.

- Chamberlain 1953, 1966, p. 23.

- Cardoza Sánchez 2017, p. 56.

- Cardoza Sánchez 2017, p. 57.

- Salamanca 2012, p. 8.

- García Buchard, p. 3.

- García Añoveros 1988, pp. 47–48.

- Rica, Costa (1914). Costa Rica-Panama Arbitration: Answer of Costa Rica to the Argument of Panama Before the Arbitrator, Hon. Edward Douglass White, Chief Justice of the United States, Under the Provisions of the Convention Between the Republic of Costa Rica and the Republic of Panama, Concluded March 17, 1910. Press of Gibson Brothers, Incorporated.

- García Añoveros 1988, p. 48.

- García Añoveros 1988, p. 53.

- García Añoveros 1988, pp. 53–54.

- García Añoveros 1988, p. 54.

- García Añoveros 1988, p. 52.

- Newson 1982, pp. 255–256.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 239.

- Ibarra Rojas 1994, p. 241. Ibarra Rojas 2001, p. 105.

- Healy 1980, 2006, p. 19.

- Orellano 1979, pp. 125, 127.

- Orellano 1979, pp. 125–126.

- Meléndez 1976, p. 239.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 49, 250.

- Meléndez 1976, pp. 50, 247.

References

- Barahona, Marvin (1991) Evolución histórica de la identidad nacional (in Spanish). Tegucialpa, Honduras: Editorial Guaymuras. ISBN 99926-28-11-1. OCLC 24399780.

- Calvo Poyato, José (September 1988). "Francisco Hernández de Córdoba y la conquista de Nicaragua." Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos. 459: 7–16, Madrid, Spain: Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana. (in Spanish)

- Cardoza Sánchez, Uriel Ramón (June 2017). "Evolución Urbana y Arquitectónica de la Ciudad de Matagalpa". Revista Arquitectura + Vol. 2, No. 3: 54–61. Managua, Nicaragua: Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería de Nicaragua. ISSN 2518-2943. Accessed on 2017-11-21. (in Spanish)

- Chamberlain, Robert Stoner (1966) [1953]. The Conquest and Colonization of Honduras: 1502–1550. New York: Octagon Books. OCLC 640057454.

- Churchill, Ward (1999). Genocide of native populations in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Basin in Israel W. Charny (ed.) Encyclopedia of Genocide. Santa Barabara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-928-2. OCLC 911775809.

- Coe, Michael D.; with Rex Koontz (2002). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28346-X. OCLC 50131575.

- Deagan, Kathleen (June 1988). "The Archaeology of the Spanish Contact Period in the Caribbean". Journal of World Prehistory Vol. 2, No. 2: 187–233. Springer. JSTOR 25800541

- Deagan, Kathleen (2003). "Colonial Origins and Colonial Transformations in Spanish America". Historical Archaeology Vol. 37, No. 4: pp. 3–13 . Society for Historical Archaeology. JSTOR 25617091. ISSN 2328-1103.

- Feldman, Lawrence H. (2000). Lost Shores, Forgotten Peoples: Spanish Explorations of the South East Maya Lowlands. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2624-8. OCLC 254438823.

- Fonseca Zamora, Oscar M. (1998). "El espacio histórico de los amerindios de filación chibcha: El área histórica chibchoide" in María Eugenia Bozzoli, Ramiro Barrantes, Dinorah Obando, Mirna Rojas (eds.) "Primer Congreso Científico sobre Pueblos Indígenas de Costa Rica y sus fronteras". San José, Costa Rica: UNICEF, Universidad Estatal a Distancia, and Universidad de Costa Rica. pp. 36–60. ISBN 978-9977649740. (in Spanish)

- Fowler, William R. Jr. (Winter 1985). "Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil-Nicarao of Central America: A Critical Analysis". Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 32 (1): 37–62. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482092. OCLC 478130795. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- García Añoveros, Jesús María (1988). "Presencia franciscana en la Taguzgalpa y la Tologalpa (la Mosquitia)". Mesoamérica. Antigua Guatemala: El Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA) in conjunction with Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies, South Woodstock, Vermont. 9: 47–78. ISSN 0252-9963. OCLC 7141215. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. (in Spanish)

- García Buchard, Ethel. Evangelizar a los indios gentiles de la Frontera de Honduras: una ardua tarea (Siglos XVII–XIX) (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica: Centro de Investigación en Identidad y Cultura Latinoamericanas (CIICLA), Universidad de Costa Rica. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08.

- Grenke, Arthur (2005). God, Greed, and Genocide: The Holocaust Through the Centuries. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing. ISBN 0-9767042-0-X. OCLC 255346071.

- Healy, Paul (2006) [1980]. A Brief History of the Culture Subarea in Archaeology of the Rivas Region, Nicaragua. pp. 19–34. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-094-7. (Full text via Project MUSE.)

- Ibarra Rojas, Eugenia (1994). "Los Matagalpas a principios del siglo XVI: aproximación a las relaciones interétnicas en Nicaragua (1552–1581)". Vínculos. 18–19 (1–2): 229–243. San José, Costa Rica: Museo Nacional de Costa Rica. ISSN 0304-3703. Archived from the original on 2017-07-26. (in Spanish).

- Ibarra Rojas, Eugenia (2001). Fronteras étnicas en la conquista de Nicaragua y Nicoya: Entre la solidaridad y el conflicto 800 d.C.-1544. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica. ISBN 9977-67-685-2. OCLC 645912024. (in Spanish)

- Leonard, Thomas M. (2011). The History of Honduras. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36303-0. OCLC 701322740.}

- Meléndez, Carlos (1976) Hernández de Córdoba: Capitán de conquista en Nicaragua. Managua, Nicaragua: Editorial San José. Serie histórica 9. OCLC 538851181. (in Spanish)

- Mena García, María del Carmen (1992) Pedrarias Dávila o "la ira de Dios": una historia olvidada. Sevilla, Spain: Universidad de Sevilla. ISBN 84-7405-834-1. (in Spanish)

- Merril, Tim (1993a). "Geography" in Nicaragua: A Country Study. Washington, D. C.: GPO for the Library of Congress. Accessed on 2017-07-11. Archived from the original on 2017-11-13.

- Montoya, Ramiro (2015). Crónicas del oro y la plata amerinanos. Madrid, Spain: Visión Libros. ISBN 978-84-16284-31-3. OCLC 952956657. (in Spanish)

- Nessler, Graham T. (2016). An Islandwide Struggle for Freedom: Revolution, Emancipation, and Reenslavement in Hispaniola 1789–1809. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-2687-1. OCLC 945632920.

- Newson, Linda (November 1982). "The Depopulation of Nicaragua in the Sixteenth Century". Journal of Latin American Studies. Cambridge University Press. 14 (2): 253–286. ISSN 0022-216X. JSTOR 156458. OCLC 4669522494. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

- Olson, James S.; Sam L. Slick; Samuel Freeman; Virginia Garrard Burnett; Fred Koestler (1992) New York Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-26413-9.

- Orellano, Jorge Eduardo (1979) "Oviedo y la provincia de Nicaragua". Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos. San José, Costa Rica: Universidad de Costa Rica. 15: 125–129. JSTOR 25661767. (in Spanish)

- Pohl, John; Hook, Adam (2008) [2001]. The Conquistador 1492–1550. Warrior. 40. Oxford and New York: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-175-6. OCLC 47726663.

- Polo Sifontes, Francis (1986). Los Cakchiqueles en la Conquista de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: CENALTEX. OCLC 82712257.

- Quirós Vargas, Claudia; and Margarita Bolaños Arquín (1989) "Una reinterpretación del origen de la dominación colonial española en Costa Rica: 1510–1569". Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos. San José, Costa Rica: Universidad de Costa Rica. 15 (1): 29–48. JSTOR 25661952. (Full text via JSTOR.) (in Spanish)

- Rowlett, Russ (2005). "Units of Measurement: L". Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Salamanca, Danilo (2012) "Los dos rostros indígenas de Nicaragua y Centroamérica". Wani, Revista del Caribe Nicaragüense. 65: 6–23. Bluefields, Nicaragua: Bluefields Indian & Caribbean University/Centro de Investigaciones y Documentacion de la Costa Atlántica (BICU/CIDCA). ISSN 2308-7862. Archived from the original on 2017-07-26 (in Spanish)

- Sariego, Jesús M. (2005) ""Evangelizar y educar" Los jesuitas de la Centroamérica colonial". Estudios Centroamericanos: ECA. Vol. 65, No. 723. San Salvador, El Salvador: Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas. ISSN 0014-1445. OCLC 163277504. (in Spanish)

- Sarmiento, José A. (2006) [1990]. Historia de Olancho 1524–1877 (in Spanish). Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Editorial Guaymuras. Colección CÓDICES (Ciencias Sociales). ISBN 99926-33-50-6. OCLC 75959569.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003) [1996]. The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, Massachusetts and Oxford,: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23016-8. OCLC 59452395

- Solórzano Fonseca, Juan Carlos (December 1992). "La búsqueda de oro y la resistencia indígena: campañas de exploración y conquista de Costa Rica, 1502–1610". Mesoamérica. Antigua Guatemala, Guatemala and South Woodstock, Vermont: El Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA) in conjunction with Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies. 24: 313–364. ISSN 0252-9963. OCLC 7141215. (in Spanish)

- Stanislawski, Dan (May 1983). The Transformation of Nicaragua 1519–1548. Ibero-Americana Volume 54. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09680-0. OCLC 470870988.

- Staten, Clifford L. (2010). The History of Nicaragua Greenwood histories of the modern nations. Santa Barbara, California and Oxford: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-36037-4. OCLC 855554817.

Further reading

- Adams, Richard N. (October 1989). "The Conquest Tradition of Mesoamerica". The Americas. Cambridge University Press. 46 (2): 119–136. doi:10.2307/1007079. JSTOR 1007079

- Higgins, Bryan (1994). "Nicaragua". In Gerald Michael Greenfield, ed., Latin American Urbanization: Historical Profiles of Major Cities Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- Lovell, W. George; and Christopher H. Lutz (1992) "The Historical Demography of Colonial Central America". Yearbook (Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers) Vol. 17/18, BENCHMARK 1990 (1991/1992): pp. 127–138. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. JSTOR 25765745. (Full text via JSTOR.).

- Merril, Tim (1993b). "Colonial Period, 1522–1820: The Spanish Conquest" in Nicaragua: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: GPO for the Library of Congress. Accessed on 2017-07-07.

- Pineda, Baron L. (2006) "Nicaragua’s Two Coasts" in Shipwrecked Identities: Navigating Race on Nicaragua's Mosquito Coast. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. pp. 21–66. ISBN 978-0-8135-3813-6. JSTOR j.ctt5hj296.4. (Full text via JSTOR.).

- Sánchez, Consuelo (July 1989). "El régimen colonial español en nicaragua". Boletín de Antropología Americana. 19: 131–161. Mexico City, Mexico: Pan American Institute of Geography and History. JSTOR 40977379. (Full text via JSTOR.). (in Spanish)

- Velasco, Balbino (1985) "El conquistador de Nicaragua y Perú Gabriel de Rojas y su testimonio (1548)". Revista de Indias. XLV (176): 373–403. Madrid, Spain: Instituto de Historia, Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales (CSIC). ISSN 0034-8341. (subscription required) (in Spanish)