Siege of Leiden

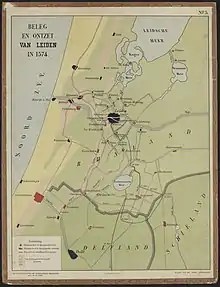

The siege of Leiden occurred during the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo–Spanish War in 1573 and 1574, when the Spanish under Francisco de Valdez attempted to capture the rebellious city of Leiden, South Holland, the Netherlands. The siege failed when the city was successfully relieved in October 1574.[1]

| Siege of Leiden | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War & the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||

Relief of Leiden by the Geuzen on flat-bottomed boats, on 3 October 1574. Otto van Veen. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pieter Adriaanszoon van der Werff (Mayor of Leiden) | Francisco de Valdez | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11,000 | 15,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 500 | 2,000 | ||||||

Background

In the war that had broken out (eventually called the Eighty Years' War), Dutch rebels took up arms against the Habsburg king of Spain, whose family had inherited the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. Most of the counties of Holland and Zeeland were occupied by rebels in 1572, who sought to end the harsh rule of the Spanish Duke of Alba, governor-general of the Netherlands. The territory had a high density of cities, which were protected by defense works and by the low-lying boglands, which could easily be flooded by opening the dykes and letting in the sea.

The Duke of Alba tried to break resistance using brute force. He used Amsterdam as a base, as this was the only city in the county of Holland that had remained loyal to the Spanish government. Alba's cruel treatment of the populations after the sieges of Naarden and Haarlem was notorious. The rebels learned that no mercy was shown there and were determined to hold out as long as possible. The county of Holland was split in two when Haarlem was taken by the Spanish after a seven-month siege. Alba then attempted to take Alkmaar in the north, but the city withstood the Spanish attack. Alba then sent his officer Francisco de Valdez to attack the southern rebel territory, starting with Leiden. In the meantime, due to his failure to quell the rebellion as quickly as he had intended, Alba submitted his resignation, which King Philip accepted in December. The less harsh and more politic Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens replaced him as governor-general.

First siege of Leiden

The city of Leiden had plenty of food stored for the siege when it started in October 1573. The siege was very difficult for the Spanish, because the soil was too loose to dig trenches, and the city's defense works were hard to break. Defending Leiden was a Dutch States rebel army consisting of English, Scottish, and Huguenot French troops.[2][3] The leader of the Dutch rebels, William the Silent, Prince of Orange, attempted a relief of Leiden by sending an army into the Netherlands under the command of his brother, Louis of Nassau. Valdez lifted the siege in April 1574 to face the invading rebel troops, but Sancho d'Avila reached them first and defeated them in the Battle of Mookerheyde, where Louis was killed.

Second siege and relief of Leiden

During the brief respite from the siege, Orange counselled the citizens of Leiden to restock their city with supplies, and take in a larger garrison to help defend the town. They disregarded his advice, however, so when Valdez' army returned to renew the siege on 26 May 1574, they were in as poor a condition as they had previously been. The city considered surrendering, as there was almost no chance of relief and supplies were dwindling. The defeat of Louis' army was also a blow to morale.

The Prince of Orange, however, was determined to relieve the city. Therefore, he sent a carrier pigeon into the city pleading for it to hold out for three months. To fulfil this promise, he planned to breach the dykes to allow the sea to flood the low-lying land. The siege could then be lifted using the rebel fleet, and the Spaniards would be forced to retire before the incoming sea. This tactic had also been used to relieve Alkmaar. The damage to the surrounding countryside would be enormous, and therefore the population of the area resisted the breaching of the dykes. However, in the end, the Prince prevailed and the outer dykes were broken on 3 August. Previously, the Prince's Admiral Louis Boisot had assembled a fleet of more than two hundred small flat-bottomed vessels, manned by 2,500 veteran Dutch seamen, and carrying a large store of provisions for the starving townspeople of Leiden. Soon after the first dykes were broken, the Prince of Orange came down with a violent fever which brought operations to a halt. More importantly, the flooding of the countryside took longer than expected because of unfavorable winds. On 21 August, the inhabitants of Leiden sent a message to the Prince saying that they had held out for three months, two with food and one without food. The Prince answered them, again by carrier pigeon, that the dykes had all been pierced and relief would come soon.[4]

However, only by the first day of September, when the Prince had recovered from his ailment, did the expedition continue in earnest. More than 15 miles lay between the relieving rebel fleet and Leiden, but ten miles were covered without difficulty. On the night of 10 September, the fleet came upon the Landscheiding, which blocked their path to Leiden, and captured it in a night-time surprise attack. The Spaniards had neglected to strongly fortify this important point. The next morning, the Spaniards tried to regain the position but were repulsed with the loss of several hundred men. The dyke was breached and the fleet proceeded towards Leiden.

Admiral Boisot and the Prince of Orange had been misinformed as to the lie of the lands, and had assumed that the rupture of the Landscheiding would flood the country inland all the way to Leiden. Instead, the rebel flotilla once again found their path blocked, this time by the Greenway dike, less than a mile inland of the Landscheiding, which was still a foot above the water level. Again however the Spaniards had left the dike largely undefended, and the Dutch broke through it without much difficulty. Due to easterly winds driving the water back seawards, and the ever growing surface area of the land that the water covered, the flooding was by this time so shallow that the fleet was all but stranded. The only way that was deep enough for them to proceed was by a canal, leading to a large inland lake called the Zoetermeer (freshwater lake). This canal, and the bridge over it, were strongly defended by the Spaniards, and after a brief amphibious struggle, the Admiral gave up the venture. He dispatched a despondent message to the Prince, saying that unless the wind turned, and they could sail around the canal, they were lost.

Meanwhile, in the city, the inhabitants clamoured for surrender when they saw that their countrymen had run aground. But Mayor van der Werff inspired his citizens to hold on, telling them they would have to kill him before the city could surrender, and that they could eat his arm if they were really that desperate. In fact thousands of inhabitants died of starvation. To add to their troubles, as so often happened in that age, the plague appeared in the city streets and near eight thousand died from that cause alone. The city only held out because they knew that the Spanish soldiers would massacre the whole population in any case, to set an example to the rest of the country, as had happened in Naarden and the other cities that had been sacked. Admiral Boisot sent a dove into the town, assuring them of speedy succour.

On the 18th the wind shifted again, and blowing strongly from the west, piled the sea against the dams. With the rising water level, the flotilla was soon able to make a circuit around the bridge and canal, and successfully enter the Zoetermeer. In October, the Dutch patriots led by William the Silent destroyed the dykes in four locations in order to form an obstacle the Spanish troops could not overcome. As a result of this and the coming of a strong wind from the West, the water rose and Spanish troops lost their mobility. On one of these four locations, a monument has been established in remembrance of what happened called the Groenedijk Monument. The Sea Beggars under Admiral Louis de Boisot had ships to successfully use the water to their advantage.[5] A succession of fortified villages now stood in the way of the patriot fleet, and the Dutch Admiral was afraid even now of losing his prize, but the Spaniards, panicked by the rising waters, barely offered any resistance. Every one of their strongholds, now become islands, were deserted by the Royalist troops in their flight, except for the village of Lammen. This was a small fort under the command of Colonel Borgia, and situated about three-quarters of a mile from the walls of Leiden.

This was a formidable obstacle, but the Spaniards, adept at land fighting and not amphibious warfare, had despaired of maintaining so unequal a contest against the combined forces of the sea and the veteran Dutch seamen. Accordingly, the Spanish commander Valdez ordered a retreat in the night of 2 October, and the army fled, rendered more fearful by a terrible crash they heard from the city, and assumed to be the men of Leiden breaking still another dam upon them. In fact, part of the wall of Leiden, eroded by the sea water, had fallen, leaving the city completely vulnerable to attack, had any chosen to remain.

The next day, the relieving rebels arrived at the city, feeding the citizens with herring and white bread. The people also feasted on hutspot (carrot and onion stew) in the evening. According to legend, a little orphan boy named Cornelis Joppenszoon found a cooking pot full with hutspot that the Spaniards had had to leave behind when they left their camp, the Lammenschans, in a hurry to escape from the rising waters.[6]

Aftermath

In 1575, the Spanish treasury ran dry, so that the Spanish army could not be paid anymore and it mutinied. After the pillaging of Antwerp, the whole of the Netherlands rebelled against Spain. Leiden was once again safe.

The Leiden University was founded by William of Orange in recognition of the city's sacrifice in the siege. According to the ironical fiction still maintained by the Prince, that he was acting on behalf of his master Philip of Spain, against whom he was in fact in open rebellion, the university was endowed in the King's name.

The 3 October Festival is celebrated every year in Leiden. It is a festival, with a funfair and a dozen open air discos in the night.[7] The municipality gives free herring and white bread to the citizens of Leiden.

Trivia

- There was an earlier siege of Leiden, in 1420.

Notes

- Fissel, p. 141

- Van Dorsten, pp. 2–3

- Trim, p. 164

- Motley, John Lothrop (1855). The Rise of the Dutch Republic.

- Battles, James B. (September 2014). "Sea Beggars, Loaves, Fishes, and Turkey: The influence of Leidens Ontzet (Relief of Leiden) on the Pilgrims Thanksgiving". The Mayflower Quarterly 136.

- Motley, John Lothrop (1855). The Rise of the Dutch Republic.

- "Leidens Onzet"

References

- Fissel, Mark Charles (2001). English warfare, 1511–1642; Warfare and history. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415214810.

- Henty, G. A. (2002). By Pike and Dyke. Robinson Books. ISBN 978-1590870419.

- Motley, John Lothrop. The Rise of the Dutch Republic, Entire 1566–74.

- Trim, David (2011). The Huguenots: History and Memory in Transnational Context. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-9004207752.

- Van Dorsten, J. A. (1962). Poets, Patrons and Professors: Sir Philip Sidney, Daniel Rogers and the Leiden Humanists. Brill: Architecture. ISBN 978-9004066052.