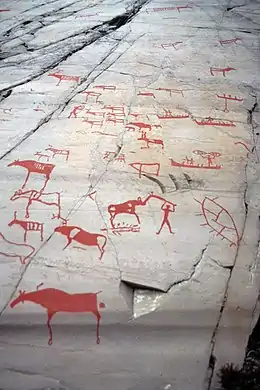

Rock carvings at Alta

The Rock art of Alta (Helleristningene i Alta) are located in and around the municipality of Alta in the county of Troms og Finnmark in northern Norway. Since the first carvings were discovered in 1973, more than 6,000 carvings have been found on several sites around Alta. The largest locality, at Jiepmaluokta about five kilometers (3.1 mi) from Alta, contains thousands of individual carvings and has been turned into an open-air museum. The site, along with the sites Storsteinen, Kåfjord, Amtmannsnes, and Transfarelv, was placed on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites on 3 December 1985. It is Norway's only prehistoric World Heritage Site.[1]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Alta, Troms og Finnmark, Northern Norway, Norway |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 352 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Area | 53.59 ha (132.4 acres) |

| Coordinates | 69°56′49″N 23°11′16″E |

Location of Rock carvings at Alta in Finnmark  Rock carvings at Alta (Norway) | |

The carvings were divided into five separate groups by Professor Knut Helskog, of the Department of Cultural Sciences at the University of Tromsø. Using shoreline dating, the earliest carvings were dated to around 4200 BC; the most recent carvings were dated to around 500 BC. In 2010, researcher Jan Magne Gjerde pushed the dates for the oldest phases back by 1,000 years. The wide variety of imagery shows a culture of hunter-gatherers that was able to control herds of reindeer, was adept at boat building and fishing, and practiced shamanistic rituals involving bear worship and other venerated animals.

In April 2014, the World Heritage Rock Art Centre - Alta museum launched the website altarockart.no, a digital archive containing pictures of the rock art of Alta. The archive contains several thousand pictures and tracings and will, in the future, probably contain other kinds of documenting material as well, such as 3D-scans and articles.

Cultural and historical background

When the carvings were made, Norway was inhabited by hunter-gatherers. The almost 5000 years over which carvings were made by the people of the late stone age and early metal age, saw many cultural changes, including the adoption of metal tools and changes in areas such as boat building and fishing techniques. The carvings show a wide variety of imagery and religious symbolism. There are however some main motifs that are found through all the periods, like the reindeer. Rock carvings especially from the earliest period show great similarity with carvings from northwestern Russia, indicating contact between and maybe parallel development of cultures over a wide area of Europe's extreme North.

Alta's rock carvings were probably made using quartzite chisels that were probably driven by hammers made from some harder rocks; probable examples of chisels have been found throughout the area and are on display in Alta Museum. Use of rock chisels seems to have continued even after metal tools came into use in the area.

Due to post-glacial rebound, Scandinavia started to rise at a considerable rate out of the ocean after the end of the last ice age. This effect is still somewhat noticeable today, but it is thought to have been much faster and probably even noticeable during a man's lifetime while Alta's rock drawings were made. It is strongly indicated that the carvings were originally directly on the shore and were gradually lifted to where they are now several dozen metres inland.

Discovery and restoration

The first carvings were discovered in autumn 1973 in the area of Jiepmaluokta (a Northern Sami name meaning "bay of seals"), about 4 kilometres from the town centre of Alta. During the 1970s, many more carvings were discovered all around Alta, with a noticeably higher density around Jiepmaluokta (of around 6000 known carvings in the area, more than 3000 are located there). A system of wooden walkways totaling about 3 kilometres was constructed in the Jiepmaluokta area during the second half of the 1980s, and Alta's museum was moved from its previous location in the town centre to the site of the rock carvings in 1991. Although several other sites around Alta are known and new carvings are constantly discovered, only the Hjemmeluft locality is part of the official tour of the museum.

Most rocks around Alta are overgrown with a thick growth of moss and lichen; once carvings have been discovered, these plants are carefully removed and the rock is cleaned to expose the full extent of the carvings. The carvings are then documented using different techniques, most often the combination of quartz powder painted into the carvings which are then photographed and digitally treated.

World Heritage Rock Art Centre - Alta Museum

World Heritage Rock Art Centre - Alta Museum features a display of objects found in the area thought to be related to the culture that created the carvings, a photographic documentation of the carvings, and displays on Sami culture, the phenomenon of Aurora Borealis and the area's history of slate mining. The museum received the European Museum of the Year Award in 1993.[2]

Imagery and interpretations

Possible explanations include use in shamanistic rituals, totemistic symbols that denoted tribal unity or marked a tribe's territory, a kind of historical record of important events, or even simple artistic pleasure. Since individual carvings show such a wide array of different images and the carvings were created over an extremely long period of time, it seems plausible that individual carvings might have served any of the purposes listed above. Some of the more common types of images are listed below:

Animals

A wide array of animals are depicted on carved scenes; among them, reindeer are clearly predominant and are often shown in large herds that are alternatively nurtured and hunted. Depictions of reindeer behind fences indicate large cooperative hunting of these animals. Other animals that appear frequently are elk, various bird species and different kinds of fish. Pregnant animals are often depicted with a young one visible inside of its mother.

Bears

Bears seem to have played a special role in the carvers' culture: they feature prominently in many carvings and frequently appear not only as animals to be hunted but are also often depicted in positions that seem to indicate that bears were worshipped in some form of cult (which seems very plausible since bear cults are known in many old cultures of northwestern Russia as well as in Sami culture).[3] Of special interest are the tracks coming out of bear dens: they are often shown with tracks leading vertically through the carved image and crossing the horizontal tracks of other animals. This has led some researchers to speculate that bears might have been in some way connected with a cult of the afterlife (or death in general) since the vertical tracks seem to indicate an ability of bears to pass between different layers of the world. The depiction of bears seems to have ceased around 1700 BC; this might indicate a change in religious beliefs around that time.

Hunting and fishing scenes

Many scenes depicting humans show hunters stalking their prey; these scenes have traditionally been explained as being connected to hunting rituals, although current researchers seem to favor more complicated explanations that see depictions of different hunting and fishing actions as symbols for individual tribes and the interrelations of different hunting and fishing carvings as symbolic representations of existing or wished-for intertribal relations. The use of throwing spears and of bows and arrows is evident from the earliest period, indicating that the use of these tools was known to the carvers' culture from a very early time. Similarly, fishermen are almost exclusively shown using fishing-lines, indicating that a method of creating hooks and using bait was known to the carvers.

Of special interest is the depiction of boats: while small fishing boats appear from the earliest drawings onward, later drawings show larger and larger boats, some carrying up to 30 people and being equipped with elaborate, animal-shaped decorations on bow and stern that are sometimes reminiscent of those found on viking longboats. This, along with the fact that similar carvings of large boats have been found in coastal regions in southern Norway, seems to indicate long distance voyages along the coast from either direction.

Scenes of mundane life and scenes of rituals

It is especially difficult to judge the meaning of scenes showing interactions between humans; scenes apparently showing a dance, the preparation of food or sexual interactions might also display the performance of rituals. Additionally, even if these carvings in fact do show episodes from mundane life, it remains mysterious why these specific scenes were carved into rock. Depictions of sexuality might be connected to fertility rituals, scenes that show people cooking and preparing food might have been meant to ensure an abundance of food. Some scenes clearly show different societal positions of the humans depicted, indicated by peculiar headgear and by more prominent positions of wearers of special headgear among their fellow humans; these have alternatively been explained as priests or shamans or as rulers of a tribe. If the interpretation of prominent persons as rulers is correct, these scenes might also display events of historical significance, such as the ascension of a ruler, royal marriages or diplomatic relations between tribes.

Geometric symbols

Among the most mysterious of the carvings are images of geometric symbols, found predominantly among the oldest carvings of the area. Some of these are circular objects, some of which are surrounded by fringes, others show intricate patterns of horizontal and vertical lines. While some of these objects have been explained as tools or similar objects (the line patterns, for example, are sometimes explained as fishing nets), most of these symbols remain unexplained.

See also

References

- Rock Art of Alta (UNESCO World Heritage Centre)

- The Rock Art of Alta (Alta Museum IKS)

- Brandon Bledsoe. "The Significance of the Bear Ritual Among the Sami and Other Northern Cultures". University of Texas, web course on Sami Culture. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

Other sources

- Knut Helskog (1988). Helleristningene i Alta. Alta (town). ISBN 82-991709-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Arvid Sveen (1996). Helleristninger. Hjemmeluft, Alta. Vadsø. ISBN 82-993932-2-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Øivind Stenersen and Ivar Libæk (2003). The History of Norway. Lysaker. ISBN 82-8071-041-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Alta Museum website

- Rock Art of Alta UNESCO Collection on Google Arts and Culture

- Norway State of Environment webpage about the carvings

- The digital rockart archive - Altarockart.no