Kiva

A kiva is a space used by Puebloans for rites and political meetings, many of them associated with the kachina belief system. Among the modern Hopi and most other Pueblo peoples, "kiva" means a large room that is circular and underground, and used for spiritual ceremonies.

Similar subterranean rooms are found among ruins in the Southwestern United States, indicating uses by the ancient peoples of the region including the ancestral Puebloans, the Mogollon, and the Hohokam.[1] Those used by the ancient Pueblos of the Pueblo I Period and following, designated by the Pecos Classification system developed by archaeologists, were usually round and evolved from simpler pit-houses. For the Ancestral Puebloans, these rooms are believed to have had a variety of functions, including domestic residence along with social and ceremonial purposes.[2]

Evolution

During the late 8th century, Mesa Verdeans started building square pit structures that archeologists call protokivas. They were typically 3 or 4 feet (0.91 or 1.22 m) deep and 12 to 20 feet (3.7 to 6.1 m) in diameter. By the mid-10th and early 11th centuries, these had evolved into smaller circular structures called kivas, which were usually 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) across. Mesa Verde-style kivas included a feature from earlier times called a sipapu, which is a hole dug in the north of the chamber that is thought to represent the Ancestral Puebloans' place of emergence from the underworld.[3][4]

When designating an ancient room as a kiva, archaeologists make assumptions about the room's original functions and how those functions may be similar to or differ from kivas used in modern practice. The kachina belief system appears to have emerged in the South-West around A.D. 1250, while kiva-like structures occurred much earlier. This suggests that the room's older functions may have been changed or adapted to suit the new religious practice.

As cultural changes occurred, particularly during the Pueblo III period between 1150 and 1300, kivas continued to have a prominent place in the community. However, some kivas were built above ground. Kiva architecture became more elaborate, with tower kivas and great kivas incorporating specialized floor features. For example, kivas found in Mesa Verde National Park were generally keyhole-shaped. In most larger communities, it was normal to find one kiva for each five or six rooms. Kiva destruction, primarily by burning, has been seen as a strong archaeological indicator of conflict and warfare among people of the South-West during this period.

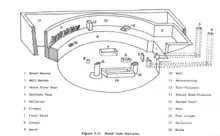

Fifteen top rooms encircle the central chamber of the vast Great Kiva at Aztec Ruins National Monument. The rooms'

... purpose is unclear. ... Each had an exterior doorway to the plaza. ... Four massive pillars of alternating masonry and horizontal poles held up the ceiling beams, which in turn supported an estimated 95-ton roof. Each pillar rested on four shaped-stone disks, weighing about 355 pounds [161 kg] apiece. These discs are of limestone, which came from mountains at least 40 miles away.[5]

After 1325 or 1350, except in the Hopi and Pueblo region, the ratio changed from 60 to 90 rooms for each kiva. This may indicate a religious or organizational change within the society, perhaps affecting the status and number of clans among the Pueblo people.

Great kiva

Great kivas differ from regular kivas, which archeologists call Chaco-style kivas (although Chaco Canyon also features great kivas), in several ways; first and foremost, great kivas are always much larger and deeper than Chaco-style kivas. Whereas the walls of great kivas always extend above the surrounding landscape, the walls of Chaco-style kivas do not, but are instead flush with the surrounding landscape. Chaco-style kivas are often found incorporated into the central room blocks of great houses, but great kivas are always separate from core structures. Great kivas almost always have a bench that encircles the inner space, but this feature is not found in Chaco-style kivas. Great kivas also tend to include floor vaults, which might have served as foot drums for ceremonial dancers, but Chaco-style kivas do not.[6] Great kivas are believed to be the first public buildings constructed in the Mesa Verde region.[7]

See also

References

- Citations

- Pecina 2012.

- Markovich, Nicholas; Preiser, Wolfgang; Sturm, Fred (2015). Pueblo Style and Regional Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-39883-7.

- Lipe 2006, pp. 30–31.

- Lipe 2006, p. 30.

- Cajete & Nichols 2004.

- Vivian & Reiter 1965, pp. 82–92.

- Hurst & Till 2006, p. 78.

- Bibliography

- Cajete, Gregory A.; Nichols, Teresa (2004), A Trail Guide to the Aztec Ruins, Western National Parks Association (WPNA)

- Hurst, Winston; Till, Jonathan (2006), "Mesa Verdean Sacred Landscapes", in Nobel, David Grant (ed.), The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Puebloan Archaeology, School of American Research Press, pp. 74–83, ISBN 978-1-930618-75-6

- Lipe, Willian D. (2006), "The Mesa Verde Region during Chaco Times", in Nobel, David Grant (ed.), The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Puebloan Archaeology, School of American Research Press, pp. 28–37, ISBN 978-1-930618-75-6

- Pecina, Ron (December 2012), "Estufa or Kiva", Indian Trader, Cottonwood Arizona: D. South, 3564 (12): 12–17

- Vivian, Gordon; Reiter, Paul (1965), The great kivas of Chaco Canyon and their relationships, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0-8263-0297-7

Further reading

- Cordell, Linda S. (1994). Ancient Pueblo Peoples. Exploring the Ancient World. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-0895990389.

- LeBlanc, Steven A. (1999). Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest. University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0874805819.

- Rohn, Arthur H.; Ferguson, William M (2006). Puebloan Ruins of the Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826339706.

External links

- La Kiva tradicional de Oscar Freire

- Perfect Kiva on YouTube

- Mule Canyon Kiva on YouTube