Prehistoric medicine

Prehistoric medicine is any use of medicine from before the invention of writing and the documented history of medicine. Because the timing of the invention of writing per culture and region, the term "prehistoric medicine" encompasses a wide range of time periods and dates.[1]

The study of prehistoric medicine relies heavily on artifacts and human remains, and on anthropology. Previously uncontacted peoples and certain indigenous peoples who live in a traditional way have been the subject of anthropological studies in order to gain insight into both contemporary and ancient practices.[2]

Disease and mortality

Some diseases and ailments were more common in prehistory than they are today; there is evidence that many people suffered from osteoarthritis, probably caused by the lifting of heavy objects which would have been a daily and necessary task in their societies. For example, the transport of latte stones, a practice started during the neolithic era, which involved hyper extension and torque of the lower back while dragging the stones, may have contributed to the development of micro fractures in the spine and subsequent spondylolysis. Things such as cuts, bruises, and breakages of bone, without antiseptics, proper facilities, or knowledge of germs, would become very serious if infected, as they did not have sufficient ways to treat infection.[3] There is also evidence of rickets, bone deformity and bone wastage (osteomalacia),[4] which is caused by a lack of vitamin D.

The life expectancy in prehistoric times was low, 25–40 years,[5] with men living longer than women; archaeological evidence of women and babies found together suggests that many women would have died in childbirth, perhaps accounting for the lower life expectancy in women than men. Another possible explanation for the shorter life spans of prehistoric humans may be malnutrition; also, men as hunters may have sometimes received better food than the woman, who would consequently have been less resistant to disease.[6]

Treatments for diseases

Plant materials

Plant materials (herbs and substances derived from natural sources)[10] were among the treatments for diseases in prehistoric cultures. Since plant materials quickly rot under most conditions, historians are unlikely to fully understand which species were used in prehistoric medicine. A speculative view can be obtained by researching the climate of the respective society and then checking which species continue to grow in similar conditions today[11] and through anthropological studies of existing indigenous peoples.[12][13] Unlike the ancient civilisations which could source plant materials internationally, prehistoric societies would have been restricted to localised areas, though nomadic tribes may have had a greater variety of plant materials at their disposal than more stationary societies.

The effects of different plant materials could have been found through trial and error.[14] Gathering and dispensing of plant materials was in most cultures handled by women, who cared for the health of their family.[15] Plant materials were an important cure for diseases throughout history.[16] This fund of knowledge would have been passed down orally through the generations.

The birch polypore fungus, commonly found in alpine environments, may have been used as a laxative by prehistoric people living in Northern Europe, since it is known to bring on short bouts of diarrhoea when ingested, and was found among the possessions of a mummified man.[17]

The use of earth and clays

Earths and clays may have provided prehistoric peoples with some of their first medicines. This is related to geophagy, which is extremely widespread among animals in the wild as well as among domesticated animals. In particular, geophagy is widespread among contemporary non-human primates.[18] Also, early humans could have learned about the use of various healing clays by observing animal behaviour. Such clay is used both internally and externally, such as for treating wounds, and after surgery (see below). Geophagy, and the external use of clay are both still quite widespread among aboriginal peoples around the world, as well as among pre-industrial populations.

Surgery

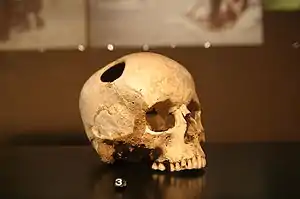

Trepanning (sometimes Trephining) was a basic surgical operation carried out in prehistoric societies across the world,[19][20] although evidence shows a concentration of the practice in Peru.[16][19][21] Several theories question the reasoning behind trepanning; it could have been used to cure certain conditions such as headaches and epilepsy.[22][23] There is evidence discovered of bone tissue surrounding the surgical hole partially grown back, so therefore survival of the procedure did occur at least on occasion.[16]

The first known trepanning operation was carried out c. 5000 BCE in Ensisheim, France.[24] A possible amputation was carried out c. 4,900 BCE in Buthiers-Bulancourt, France.

Many prehistoric peoples, where applicable (geographically and technologically), were able to set broken or fractured bones using clay materials. An injured area was covered in clay, which then set hard so that the bone could heal properly without interference.[1] Also, primarily in the Americas, the pincers of certain ant species were used to close up wounds from infection; the ant was held above the wound until it bit, where its head would be removed allowing the pincers to remain and hold closed the wound.[25]

Magic and medicine men

Medicine men (also witch-doctors, shamans) maintained the health of their tribe by gathering and distributing herbs, performing minor surgical procedures,[27] providing medical advice, and supernatural treatments such as charms, spells, and amulets to ward off evil spirits.[28] In Apache society, as would likely have been the case in many others, the medicine men initiate a ceremony over the patient, which is attended by family and friends. It consists of magic formulas, prayers, and drumming. The medicine man then, from patients' recalling of their past and possible offenses against their religion or tribal rules, reveals the nature of the disease and how to treat it.

They were believed by the tribe to be able to contact spirits or gods and use their supernatural powers to cure the patient, and, in the process, remove evil spirits. If neither this method nor trepanning worked, the spirit was considered too powerful to be driven out of the person. Medicine men would likely have been central figures in the tribal system, because of their medical knowledge and because they could seemingly contact the gods. Their religious and medical training were, necessarily, passed down orally.[29]

Dentistry

The earliest example of a drilled and filled in tooth dates back to 13,000 years ago in Italy where a tooth was filled with a mix of bitumen, hair and plant fiber. [30] Archaeologists in Mehrgarh in Balochistan province in the present day Pakistan discovered that the people of Indus Valley civilization from the early Harappan periods (c. 3300 BC) had knowledge of medicine and dentistry. The physical anthropologist who carried out the examinations, Professor Andrea Cucina from the University of Missouri, made the discovery when he was cleaning the teeth from one of the men. Later research in the same area found evidence of teeth having been drilled dating to 7,000 BCE.[31]

The problem of evidence

There is no written evidence that can be used for investigation into the prehistoric period of history by definition. Historians must use other sources such as human remains and anthropological studies of societies living under similar conditions. A variety of problems arise when the aforementioned sources are used.

Human remains from this period are rare and many have undoubtedly been destroyed by burial rituals or made useless by damage.[32][33] The most informative archaeological evidence are mummies, remains which have been preserved by either freezing or in peat bogs;[34][35] no evidence exists to suggest that prehistoric people mummified the dead for religious reasons, as Ancient Egyptians did. These bodies can provide scientists with subjects' (at the time of death): weight, illnesses, height, diet, age, and bone conditions,[36] which grant vital indications of how developed prehistoric medicine was.

Not technically classed as 'written evidence', prehistoric people left many kinds of paintings, using paints made of minerals such as lime, clay and charcoal, and brushes made from feathers, animal fur, or twigs on the walls caves. Although many of these paintings are thought to have a spiritual or religious purpose,[37] there have been some, such as a man with antlers (thought to be a medicine man), which have revealed some part of prehistoric medicine. Many cave paintings of human hands have shown missing fingers (none have been shown without thumbs), which suggests that these were cut off for sacrificial or practical purposes, as is the case among the Pygmies and Khoikhoi.[38]

The writings of certain cultures (such as the Romans) can be used as evidence in discovering how their contemporary prehistoric cultures practiced medicine. People who live a similar nomadic existence today have been used as a source of evidence too, but obviously, there are distinct differences in the environments in which nomadic people lived; prehistoric people who once lived in Britain for example, cannot be effectively compared to aboriginal peoples in Australia, because of the geographical differences.[39]

See also

References

- Kelly, Nigel; Rees, Bob; Shuter, Paul (2003). Medicine Through Time. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-30841-4.

- "Traditional Medicine". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- "The History of Medicine, Pre-history". Student reference and support materials. St Boniface's College. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- "Babylon to Birmingham, A short journey through medicine to the end of the 18th Century". Revolutionary Players. History West Midlands. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Schools History Project (26 September 1996). Medicine & Health Through Time: an SHP Development Study. Hodder Education. ISBN 978-0719552656.

- "Prehistoric Medicine". HealthGuidance.Org. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- Browning, Marie (1999). Natural Soapmaking. Sterling Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8069-6289-4.

- "Aboriginal Plant Use in SE Australia". Australian Government, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 2015-05-13. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- "Medical use of Spices". UCLA Library, History and Special collections. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- "Use Of Spices As Medicines". UCLA Library, History and Special collections. Retrieved 2009-02-19. Mentions spices being used by some prehistoric cultures

- Lock, Robin (2002). Plants of the Humid Tropics Biome. Eden Project books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-90391913-2.

- Moerman, Daniel E. (2009). Native American Medicinal Plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. Portland, OR / London: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-987-4.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Native American Herbal Remedies". Cherokee Messenger. Cherokee Cultural Society of Houston. 1996. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- Schools History Project. "BBC - GCSE Bitesize, Prehistoric Civilisation". GCSE Bitesize. BBC.

They have done this through a process of trial and error and natural selection.

- Hobbs, Christopher (6 December 2000). "Herbal Medicine: An Outline of The History of Herbalism An Overview and Literature Resource List". healthy.net. HealthWorld Online. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

... women prepared food and healing potions--women generally practiced herbalism on a day to day basis, taking care of the ills of other members of the family or tribal unit

- "Primitive Medicine". HistoryWorld. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- Wilford, John Noble (December 8, 1998). "Lessons in Iceman's Prehistoric Medicine Kit". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- Krishnamani, R.; Mahaney, William C. (2000). "Geophagy among primates: Adaptive significance and ecological consequences". Animal Behaviour. 59 (5): 899–915. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1376. PMID 10860518. S2CID 43702331.

- "Pre-Columbian Trephination". NEUROSURGERY://ON-CALL/Cyber Museum of Neurosurgery. American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Archived from the original on 2018-10-20. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- Piek J, Lidke G, Terberger T, von Smekal U, Gaab MR (July 1999). "Stone age skull surgery in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: a systematic study". Neurosurgery. 45 (1): 147–51, discussion 151. doi:10.1097/00006123-199907000-00033. PMID 10414577. A small but informative text

- "Trephination, An Ancient Surgery". UIC Oral Sciences OSCI 590: Hominid Evolution, Dental Anthropology, and Human Variation. University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

In Peruvian practice there is considerable evidence that many of the operations were performed for the naturalistic purpose of removing a bone fragment ... and trephination undertaken as a supernatural curative procedure by shamans (sancoyoc) with little technical ability as surgeons.

- Siegfried, Juliette. "History of Brain Surgery". Brain-Surgery.com. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- Osler, Sir William (1922). The Evolution of Modern Medicine: A Series of Lectures Delivered at Yale University on the Silliman Foundation in April, 1913. Silliman memorial lectures. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 6–9. See the section "Origin Of Medicine"

- Walker AA (September–October 1997). "Neolithic Surgery". Archaeology Magazine Archive. 50 (5).

- Gudger, E. W. (1925). "Stitching Wounds With the Mandibles of Ants and Beetles". J. Am. Med. Assoc. 84: 1861–4.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1994). Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-585-12190-1.

- "Mysteries of Africa". Encounter South Africa. Encounter Magazine. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2015. Stories of Medicine Men in Africa

- Ackerknecht, Erwin Heinz (1982) [1955]. A Short History of Medicine (Johns Hopkins Paperbacks ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2726-6.

- "Healing Secrets of Aboriginal Bush Medicine". Big River Internet. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

Trained from an early age by their elders and initiated into the deepest of tribal secrets...

- "Oldest tooth filling was made by an Ice Age dentist in Italy".

- "Stone age man used dentist drill". BBC News. 2006-04-06. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Coulson, Ian. "Prehistoric Medicine In Kent". The History of Health and Medicine in Kent. Kent County Council. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

It is a matter of luck because only some skeletons survive

- Wikipedia's Ötzi the Iceman Article '..three or four of his right ribs had been squashed when he had been lying face down after death, or where the ice had crushed his body.'

- "myDigiGuide: The Best UK TV Guide". www.mydigiguide.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- Malam, John (2001). Secret Worlds: Mummies, and the Secrets of Ancient Egypt. Megabites. DK Children. ISBN 978-0-78947976-1.

- Wikipedia's Article on the Mummy Juanita

- Ganeri, Anita; Martell, Hazel Mary; Williams, Brian (2007). World History Encyclopedia: A Complete and Comprehensive Guide to the History of the World. Parragon. ISBN 978-1-40549120-4.

- Janssens PA (October 1957). "Medical Views on Prehistoric Representations of Human Hands". Med Hist. 1 (4): 318–22. doi:10.1017/s0025727300021499. PMC 1034309. PMID 13476920. Pages 318–21 are of particular interest in this subject

- "Prehistoric Medicine". History GCSE / History of Medicine Lessons. Education Forum. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

External links

- Sem, Tatyana. "Shamanic Healing Rituals". Russian Museum of Ethnography.