Robert L. Dale

Robert Dale (October 14, 1924 – June 22, 2020), known as Bob Dale, was an American aircraft pilot for the United States Navy from 1942 to 1966; and a pilot for the National Science Foundation from 1967 to 1975. For his efforts as a pilot in Antarctica as Lieutenant Commander, USN, and part of the Antarctic Operation Deep Freeze (1959–1960), Dale Glacier was named after him by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) in 1963.

Robert L. Dale | |

|---|---|

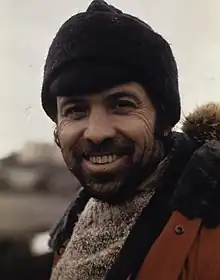

Dale at McMurdo Station, 1972 | |

| Born | October 14, 1924 |

| Died | June 22, 2020 (aged 95) |

| Other names | Bob Dale |

| Education | B.A. of Science in geology |

| Alma mater | GWU, 1959 |

| Occupation | Aircraft pilot |

| Years active | 1945–1975 |

| Employers | |

| Political party | Green Party |

| Military career | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1945–1966 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Assignments | Operation Deep Freeze V |

| Awards | |

Early life

Dale was born October 14, 1924, in Colton, California to Lula Irena Walters and Charles Dale. He is the oldest of four children.[1]

U.S. Navy career

WWII

At the age of 18 in 1942 Dale entered Flight Preparatory School, at the University of Texas at Austin. From there entering Primary Flight Training at Naval Air Station Bunker Hill, Indiana. He earned his gold wings as a United States Naval Aviator in 1945 and was stationed at Naval Air Station Pensacola, flying the Chance-Vought F4U Corsair.[2]

Post WWII

As Lieutenant (j.g.) USNR, from 1946 to 1949 Dale was assigned as a flight Instructor to Cory Field in Pensacola, Florida where he trained pilots formation flying and aerobatics such as loops, rolls, spins, precision maneuvers, takeoffs, landings, and instrument control reading.[3]

Korean War

During the Korean War, as a lieutenant (USNR), Dale learned to speak Russian, and was certified as an interpreter.[4] Later in his career, Dale would teach the Russian language to scientists while stationed in Antarctica.[5]

In 1953, Dale was stationed at Naval Air Station North Island San Diego as part of the Heavy Attack Squadron VC-6, where he flew the Savage AJ-1, a three engine plane and the first capable aircraft to deliver the Atom Bomb via aircraft carrier.[6][7][8] In mid-1953 Dale was transferred to the Naval Air Facility in Atsugi, Japan, where he flew classified missions, practicing bombing runs, Japan acting as a stand-in target. Nuclear weapons were not on board during these training missions, however the Savage was equipped with a dummy bomb to simulate the weight.[9][10][11]

In 1955 Dale received a commission with the U.S. "Regular" Navy. As Lieutenant Commander, USN.[12]

While in the U.S. Navy (1959), Dale received his bachelor's degree from George Washington University graduating cum laude, majoring in geology.[1][13] Count Geza Teleki, ph.D, a Geology professor at the university[14] and Dale's mentor, encouraged him to take part in the U.S. Antarctic Research Program (USARP).[13]

Deep Freeze V and Dale Glacier (1959–1960)

As Lieutenant Commander, USN, and part of Antarctic Operation Deep Freeze (1959–1960), Dale was Officer In-Charge of the "wintering-over" Air Development Squadron Six (VX-6) Detachment Alpha at McMurdo Station.[15] He was part of a team that flew scientist to remote, unexplored, mountain ranges and ice sheets to collect samples, run experiments and compile scientific data.[15][16]

On February 10, 1960, Dale and his crew, evacuated the USARP Victoria Land Traverse (VLT), on Rennick Glacier, and conducted an aerial photographic reconnaissance to Rennick Bay on the coast before returning the VLT team to McMurdo Station.[17][18]

For Dale's efforts, the Dale Glacier (78°17′S 162°2′E) was named after him by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) in 1963.[19]

During Deep Freeze 5, Dale and his VX-6 Squadron carried out the first flight of land-based aircraft from Christchurch New Zealand to Antarctica and carried out the longest logistics flight in Antarctic history, at that point in time. Dale and his squadron photo mapped hundreds of thousands of square miles of Antarctica; and developed new, improved techniques in polar navigation.

National Science Foundation

After retiring from the Navy in 1966 (CDR, USN), Dale continued his Antarctic explorations as a representative of the National Science Foundation (NSF) from 1967 until 1975.[13][21]

IWSOE

In 1967–68 while working for the Office of Polar Programs (OPP) as a USARP Representative for NSF, Dale oversaw the International Weddell Sea Oceanographic Expeditions-68; setting up a plan to outfit the U.S. Coast Guard's USS Glacier, icebreaker with trawling winches, other oceanographic equipment and scientific laboratories.[22][23] This would-be the first comprehensive oceanographic survey of the Weddell Sea, supporting Norwegian scientists placing an array of underwater current meters on the continental slope to measure the flow of Antarctic bottom water.[23]

R/V Hero

During Deep Freeze 1968–1969, Dale succeeded the retired John "Jack" Crowell, who oversaw the construction and launch of the floating scientific laboratory Research Vessel Hero; Dale underwent sea trials on the coast of Maine where the Hero was built, meeting them at Palmer Station in Antarctica. As the NSF Representative (Special Projects Officer),[24][7][21] Dale would spend a lot of his career in Antarctica on the Hero.

Deception Island

in 1969 while in Washington, D.C. and preparing for Deep Freeze '70–'71, Dale learned of the volcanic eruption at Deception Island, Antarctica. He helped in assembling a team of scientists who compiled research on dating the various eruptions over the years. Dale, as the NSF Representative in 1971 accompanied the scientists to and from Deception Island.[25][21]

Jacques Cousteau

During Deep Freeze 1971–72 Deception Island was visited by Jacques Cousteau, the famous oceanographer and his ship, the Calypso. Dale as the NSF Representative agreed to supply the Calypso with needed fuel but the next day a crew member was killed by the tail rotor of a tiny Helicopter on the stern of the Calypso. Their cruise was abruptly terminated.[26]

National Geographic

During Deep Freeze 1971–1972, National Geographic Magazine was on board the Hero writing a story about Palmer Station, Deception Island, and the R/V Hero. Dale was quoted while talking to a new batch of scientists that just came to Palmer Station.[27]: 630

Please don't go up to the glacier without a guide, you can fall into a crevasse before you know it's there. We are here to help you in your research in anyway we can-but we'd rather not have to do it with rescue ropes and a stretcher.

Even after hearing this statement from Dale, the author of the article, Samuel W. Matthews, fell into a crevasse and had to be rescued by glaciologists Olav Orheim and Terence Hughes.[27]: 643

Antarctican Society

In 2008 Dale donated over 2,000 slides to The Antarctician Society, documenting his time in Antarctica. The slides were then digitized.[28]

McMurdo Station, Antarctica 1964

McMurdo Station, Antarctica 1964 Palmer Station Antarctica, 1968 Anvers Island

Palmer Station Antarctica, 1968 Anvers Island Ice and Mountains in Antarctica, 1969

Ice and Mountains in Antarctica, 1969 Lindbald Explorer, Paradise Bay Antarctica, 1970

Lindbald Explorer, Paradise Bay Antarctica, 1970 Esperanza Station, Antarctica 1968

Esperanza Station, Antarctica 1968

Personal life

On September 28, 1945, Dale married Norma M. Cundiff in Riverside, California. They had three children and were divorced in 1971. Their children include Jeffrey Norman Dale (January 30, 1949), Robert Kimberly Dale (November 3, 1951) and Marina Leigh Dale Passano (March 9, 1956).[1]

Friendship with Igor Alekseevich Zotikov

Igor Alekseevich Zotikov (Russian: Зотиков, Игорь Алексеевич) and Dale met at Deep Freeze V in 1965 and became lifelong friends. Zotikov was a Soviet glaciologist, who in 1960, with the materials from the results of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), wrote his thesis predicting freshwater lakes under the thickness of the Antarctic ice.[29][30]

For his work in the Antarctic, Zotikov was awarded a glacier named after him, Zotikov Glacier.

Zotikov consulted with Dale for his book Winter Soldiers; he died in 2010 before it could be published.[31]

Later life, retirement and death

In 1986, only a year after its inception of the Maine chapter, Dale joined the Veterans for Peace organization.[32] and was highly involved in activism and protesting war.[11]

In 1988 Dale journeyed to Canton, China, where in 1953, he flew simulated atom bomb attacks in Japan, Canton being his actual target had the order been given. During this journey to Canton, Dale came to terms with his past and realized that Peace was his Passion.[11]

In 1996 Dale married Jean Parker while on vacation in Mexico.,[33] legalizing their marriage in the states on December 3, 1996, and became Stepfather to her 5 children (Nance Parker, Lisa Parker, Stephen Parker, Janet Parker and Danny Parker).[1] Dale and Parker lived on Hockomock Island, in Woolwich, Maine.[33]

During the sea trials of the research vessel Hero, Dale fell in love with Maine's coast. Finding a forested island in Hockomock Bay Woolwich, he built by hand, a self sustaining solar powered log home.[7] While living on the island, Dale and Parker grew their own food and lived off-the-grid.[33]

On June 22, 2020, Dale died at his home in Brunswick, Maine. His ashes were spread over Hockomock Island, Woolwich, Maine.[1]

Awards and honors

Publications

- Dale, Bob. "A Journey Toward Peace", 23 September 2014, Lulu Press Inc.

- Parker, Jean; Dale, Bob "On the Road with Jean and Bob", 6 December 2016, Lulu Press Inc.

References

- "Obituary". funeralalternatives.net. 22 June 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Robert Dale – Naval Aviator" (PDF). archive.org. 1945. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- "Robert Dale – Flight Instructor" (PDF). archive.org. 1946. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- "Certificate for Russian language by the US Navy" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Associated, Press (5 December 1960). "McMurdo 'College' Hums". The Christian Science Monitor. Vol. 52, no. 142. p. 4.

- "Robert Dale – AJ Certificate" (PDF). archive.org. 1953. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- George, Robert (20 July 1997). "Voices of New England – Bob Dale". The Boston Globe. Maine. p. 87.

- "AJ Savage Bomber (Historical Snapshot)". boeing.com. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Robert Dale – Classified" (PDF). archive.org. 1953. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Ginter, Steve (1992). North American AJ Savage. p. 77. ISBN 094-2-61222-1.

- Dale, Bob (3 May 2017). "Hudner Protest – A Veteran's Perspective". The Times Record. Maine.

- Congressional Record – Senate, "The following-named for permanent appointment", p. 21. 10 June 1955. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Henderson, Tom (October 2020), "CDR Robert L. Dale, USN (Ret.)" (PDF), The Antarctican Society, 20–21: 12

- "Geza Teleki, Ph.D." (PDF). dalepetersonauthor.com. 7 January 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- R. I., Stephen (1961), "Story of the Wintering Over Party, Deep Freeze 59–60" (PDF), Post WWII Antarctica Cruisebooks, National Science Foundation: 4, 7, 126

- Robert Buckhorn, "Is it cold in Antarctica?", Pensacola News Journal, p. 7. 20 February 1966. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Weihaupt, Fred G. (2012). Impossible Journey: The Story of the Victoria Land Traverse 1959–1960. Antarctica: Geological Society of America. p. 107. ISBN 9780813724881.

- "Research on Ice, An Adventure in Antarctica". Courier (GWU): 15. March 1960.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from "Robert L. Dale". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Robert L. Dale". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. - "OAE CDR Robert "Bob" L. Dale, USN (Ret)" (PDF). Explorer's Gazette. Old Antarctic Explorers Association. 20 (2): 26. June 2022.

- Dale, Robert L. (August 1968). "International Weddell Sea Oceanographic Expedition-1968" (PDF). Antarctic Journal of the United States: 7.

- Diller, Marty (Summer 2004). "1968 Weddell Sea Expedition" (PDF). Antarctic Journal of the United States: 13.

- Lagerbom, Charles H. (2 August 2021). Maine to Cape Horn, The World's Most Dangerous Voyage. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-43967-320-1.

Dale was a major background figure in the Hero's daily life and relieved Crowell when he retired as the Hero Project Officer in late 1967.

- "International Weddell Sea Oceanographic Expedition-1971", Antarctic Journal of the United States, August 1971, p. 60, Retrieved 31 July 2022

- Spindler, Bill. "Hero and Calypso at Deception Island". palmerstation.com. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- Matthews, Samuel W. (November 1971), "Antarctica's Nearer Side", National Geographic, Antarctica, pp. 622–655

- Lagerbom, Charles H. "Save the Slides Campaign" (PDF). The Antarctican Society. 8 (4): 3. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Zotikov, I.A. (1963). "Bottom melting in the central zone of the ice shield of the Antarctic continent and its influence upon the present balance of the ice mass". International Association of Scientific Hydrology. Taylor and Francis Online. 8 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1080/02626666309493295. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- Siegert, Martin J. (2017). "A 60-year international history of Antarctic subglacial lake exploration" (PDF). imperial.ac.uk. p. 4.

- Dale, Bob (September 2010). "Igor Zotikov Dies" (PDF). The Antartician Society. p. 4. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Veterans for Peace, Maine Chapter". 26 June 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Ferriss, lloyd (15 December 1996). "Island Couple's Living, and Loving their Self-Sufficient Life". Portland Press Herald. Maine. p. 68. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "WWII Victory Medal" (PDF). archive.org. 1946. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

External links

- Bob Dale Remembrance at YouTube

- The Antarctican Society

Media related to Bob Dale Collection at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bob Dale Collection at Wikimedia Commons