Puerto Ricans in World War II

Puerto Ricans and people of Puerto Rican descent have participated as members of the United States Armed Forces in the American Civil War and in every conflict which the United States has been involved since World War I. In World War II, more than 65,000 Puerto Rican service members served in the war effort, including the guarding of U.S. military installations in the Caribbean and combat operations in the European and Pacific theatres.[lower-alpha 1]

Puerto Rico was annexed by the United States in accordance to the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898, ratified on December 10, 1898, as consequence of the Spanish–American War. U.S. Citizenship was imposed upon Puerto Ricans as a result of the 1917 Jones-Shafroth Act (the Puerto Rican House of Delegates rejected US citizenship) and were expected to serve in the military.[2] When an Imperial Japanese Navy carrier fleet launched an unexpected attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Puerto Ricans were required to bear arms in defense of the United States.

During World War II, it is estimated by the Department of Defense that 65,034 Puerto Ricans served in the U.S. military.[3][4] Most of the soldiers from the island served in either the 65th Infantry Regiment or the Puerto Rico National Guard. As the induction of Puerto Ricans into the armed forces increased many were assigned to units in the Panama Canal Zone and the British West Indies to replace the continental troops serving in regular Army units.[5] Those who resided in the mainland of the United States were assigned to regular units of the military. They were often subject to the racial discrimination that was widespread in the United States at the time.[4]

Puerto Rican women who served had their options restricted to nursing or administrative positions. In World War II some of the island's men played active roles as commanders in the military. The military did not keep statistics with regard to the total number of Hispanics who served in the regular units of the Armed Forces, only of those who served in Puerto Rican units; therefore, it is impossible to determine the exact number of Puerto Ricans who served in World War II.[6]

Lead-up to World War II

Before the United States entered World War II Puerto Ricans were already fighting on European soil in the Spanish Civil War. The Spanish Civil War was a major conflict in Spain that started following an attempted coup d'état committed by parts of the army, led by the Nationalist General Francisco Franco, against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. Puerto Ricans fought on behalf of both of the factions involved, the "Nationalists" as members of the Spanish Army and the "Loyalists" (Republicans) as members of the Abraham Lincoln International Brigade.[7]

Among the Puerto Ricans who fought alongside General Franco on behalf of the Nationalists was General Manuel Goded Llopis (1882–1936), a high-ranking officer in the Spanish Army. Llopis, who was born in San Juan, was named Chief of Staff of the Spanish Army of Africa, after his victories in the Rif War, took the Balearic Islands and by order of Franco, suppressed the rebellion of Asturias. Llopis was sent to lead the fight against the Anarchists in Catalonia, but his troops were outnumbered. He was captured and was sentenced to die by firing squad.[8][9]

Among the many Puerto Ricans who fought on behalf of the Second Spanish Republic as members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, was Lieutenant Carmelo Delgado Delgado (1913–1937), a leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party from Guayama who upon the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War was in Spain in pursuit of his law degree. Delgado was an anti-fascist who believed that the Spanish Nationalists were traitors. He fought in the Battle of Madrid, but was captured and was sentenced to die by firing squad on April 29, 1937; he was amongst the first US citizens to die in that conflict.[10]

In 1937, Japan invaded China and in September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. In October 1940, the 295th and 296th Infantry Regiments of the Puerto Rican National Guard, founded by Major General Luis R. Esteves, were called into Federal Active Service and assigned to the Puerto Rican Department in accordance with the existing War Plan Orange.[11] During that period of time, Puerto Rico's economy was suffering from the consequences of the Great Depression, and unemployment was widespread. Unemployment was one of the reasons that some Puerto Ricans chose to join the Armed Forces.[12]

Most of these men were trained in Camp Las Casas in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and were assigned to the 65th Infantry Regiment, a segregated unit made up mostly of White Puerto Ricans. The rumors of war spread, and the involvement of the United States was believed to be a question of time. The 65th Infantry was ordered to intensify its maneuvers, many of which were carried out at Punta Salinas near the town of Salinas in Puerto Rico.[13] Those who were assigned to the 295th and 296th regiments of the Puerto Rican National Guard received their training at Camp Tortuguero near the town of Vega Baja.

World War II

There weren't any Puerto Rican military related fatalities when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service attacked Pearl Harbor. However, there was one civilian Puerto Rican fatality. Daniel LaVerne was a Puerto Rican amateur boxer who was working at Pearl Harbor's Red Hill underground fuel tank construction project when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He died as a result of the injuries which he received during the attack. His name is listed among the 2,338 Americans killed or mortally wounded on December 7, 1941, in the Remembrance Exhibit in the back lawn of the USS Arizona Memorial Visitor Center at Pearl Harbor.[14]

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into the war, the Puerto Ricans living on the island and on the U.S. mainland began to fill the ranks of the four major branches of the Armed Forces. Some volunteered for patriotic reasons, some joined in need of employment, and others were drafted.[5] Some families had multiple members join the Armed Forces. Seven brothers of the Medina family known as "The fighting Medinas", fought in the war. They came from Rio Grande, Puerto Rico and Brooklyn, New York.[15] In some cases Puerto Ricans were subject to the racial discrimination which at that time was widespread in the United States.[4] In 1943, there were approximately 17,000 Puerto Ricans under arms, including the 65th Infantry Regiment and the Puerto Rico National Guard. The Puerto Rican units were stationed either in Puerto Rico or in the Virgin Islands.[5]

On December 8, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked the U.S. military installations in the Philippines, Col. Virgilio N. Cordero was the Battalion Commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment.[16] The 31st Infantry covered the withdrawal of American and Philippine forces to the Bataan Peninsula and fought for four months, despite the fact that no help could come in from the outside after much of the United States Pacific Fleet was destroyed at Pearl Harbor and mid-ocean bases at Guam and Wake Island were lost.

Cordero was named Regimental Commander of the 52nd Infantry Regiment of the new Filipino Army, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican to command a Filipino Army regiment. The Bataan Defense Force surrendered on April 9, 1942, and Cordero and his men underwent torture and humiliation during the Bataan Death March and nearly four years of captivity. Cordero was one of nearly 1,600 members of the 31st Infantry who were taken as prisoners. Half of these men perished while prisoners of the Japanese forces. Cordero gained his freedom when the Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1945.[17][18]

France's possessions in the Caribbean began to protest against the Vichy government in France, a government backed by the Germans who invaded France. The island of Martinique was on the verge of civil war. The United States organized a joint Army–Marine Corps task force, which included the 295th Infantry (minus one battalion) and the 78th Engineer Battalion, both from Puerto Rico for the occupation of Martinique. The use of these infantry units was put on hold because Martinique's local government decided to turn over control of the colonies to the French Committee of National Liberation.[5]

A small detachment of insular troops from Puerto Rico was sent to Cuba in late March as a guard for Batista Field. In 1943, the 65th Infantry was sent to Panama to protect the Pacific and the Atlantic sides of the isthmus. An increase in the Puerto Rican induction program was immediately authorized and continental troops such as the 762nd, 766th, and the 891st Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalions, were replaced by Puerto Ricans in Panama.[19][20] They also replaced troops in bases on British West Indies as well, to the extent permitted by the availability of trained Puerto Rican units. The 295th Infantry Regiment followed the 65th Infantry in 1944, departing from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to the Panama Canal Zone.[5] Among those who served with the 295th Regiment in the Panama Canal Zone was a young Second Lieutenant by the name of Carlos Betances Ramírez, who would later become the only Puerto Rican to command a Battalion in the Korean War.[21] On November 25, 1943, Colonel Antulio Segarra, proceeded Col. John R. Menclenhall as Commander of the 65th Infantry, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican Regular Army officer to command a Regular Army regiment.[22]

In January 1944, the 65th Infantry embarked for Jackson Barracks in New Orleans and later to Fort Eustis in Newport News, Virginia, in preparation for overseas deployment to North Africa. For some Puerto Ricans, this would be the first time that they were away from their homeland. Being away from their homeland for the first time would serve as an inspiration for the compositions of two Puerto Ricans Boleros; "En mi viejo San Juan" (In my Old San Juan) by Noel Estrada[23] and "Despedida" (My Good-bye), a farewell song written by Pedro Flores and interpreted by Daniel Santos.[24]

Once in North Africa, the Regiment underwent further training at Casablanca. By April 29, 1944, the Regiment had landed in Italy and moved on to Corsica.[25] On September 22, 1944, the 65th Infantry landed in France and was committed to action on the Maritime Alps at Peira Cava. On December 13, 1944, the 65th Infantry, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila, relieved the 2nd Battalion of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a Regiment which was made up of Japanese Americans under the command of Col. Virgil R. Miller, a native of Puerto Rico. The 3rd Battalion fought against and defeated Germany's 34th Infantry Division's 107th Infantry Regiment.[26] There were 47 battle casualties, including Private Sergio Sanchez-Sanchez and Sergeant Angel Martinez from the town of Sabana Grande, who became the first two Puerto Ricans to be killed in combat action from the 65th Infantry as a result of a German assault on Company "L". On March 18, 1945, the regiment was sent to the District of Mannheim and assigned to military occupation duties. Twenty-three (23) soldiers of the regiment were killed in action.[27][28]

On January 12, 1944, the 296th Infantry Regiment departed from Puerto Rico to the Panama Canal Zone. In April 1945, the unit returned to Puerto Rico and soon after was sent to Honolulu, Hawaii. The 296th arrived on June 25, 1945 and was attached to the Central Pacific Base Command at Kahuku Air Base.[29] Lieutenant Colonel Gilberto Jose Marxuach, "The Father of the San Juan Civil Defense", was the commander of the 1114th Artillery and the 1558th Engineers Company's.[30]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Puerto Ricans who were fluent in English or who resided on the mainland were assigned to regular Army units. Such was the case of Sgt. First Class Louis Ramirez, who was assigned to the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized, which landed at Normandy on D-Day (Battle of Normandy), June 6, and advanced into France during the Battle of Saint-Malo, where they were met by enemy tanks, bombs, and soldiers. PFC Fernando Pagan was also a Puerto Rican who resided on the mainland; he was assigned to unit Company A, 293 Combat Engineering Battalion, which arrived in Normandy on June 10. Others, like Frank Bonilla, were assigned to the 290th Infantry Regiment, 75th Infantry Division, which later fought in the front lines at the Battle of the Bulge. Bonilla was the recipient of the Silver Star and Purple Heart medals for his actions in combat.[31] One Puerto Rican who earned a Bronze Star in the Battle of the Bulge was PFC Joseph A. Unanue, whose father was the founder of Goya Foods. Unanue had trained for armored infantry, and went to the European Theater as a gunner in A company, 63rd Armored Infantry Battalion, 11th Armored Division. His company landed in France in December 1944, just before the Battle of the Bulge.[32][33][34] PFC Santos Deliz was assigned to Battery D, 216 AAA, a gun battalion, and sent to Africa in 1943 to join the Third Army. According to Deliz, General Patton demanded the best from all under him, including cooks and kitchen hands. Deliz, who earned a Bronze Star Medal, once recounted an experience which he had with General Patton:

Patton went in to inspect and he scolded me because I had rations over the amount I should've had. The rations were food the GIs didn't want, so instead of dumping it, I sometimes gave it to the people who were around there.[35]

It was during this conflict that CWO2 Joseph B. Aviles Sr., a member of the United States Coast Guard and the first Hispanic-American to be promoted to Chief Petty Officer, received a war-time promotion to Chief Warrant Officer (November 27, 1944), thus becoming the first Hispanic American to reach that level as well.[36] Aviles, who served in the United States Navy as Chief Gunner's Mate in World War I, spent most of the war at St. Augustine, Florida training recruits.

Homefront

In 1939, a survey was conducted of possible air base sites. It was determined that Punta Borinquen was the best site for a major air base. Later that year, Major Karl S. Axtater assumed command of what was to become "Borinquen Army Air Field". The first squadron based at Borinquen Field was the 27th Bombardment Squadron, consisting of nine B-18A Bolo medium bombers. In 1940, the air echelon of the 25th Bombardment Group (14 B-18A aircraft and two A-17 aircraft) arrived at the base from Langley Field.[37]

During World War II, the following squadrons were assigned to the airfield:

- Headquarters, 13th Composite Wing, 1 November 1940 – 6 January 1941; 1 May-25 October 1941

- Headquarters, 25th Bombardment Group, 1 November 1940 – 1 November 1942; 5 October 1943 – 24 March 1944

- 417th Bombardment Squadron, 21 November 1939 – 13 April 1942 (B-18 Bolo)

- 10th Bombardment Squadron, 1 November 1940 – 1 November 1942 (B-18 Bolo)

- 12th Bombardment Squadron, 1 November 1940 – 8 November 1941 (B-18 Bolo)

- 35th Bombardment Squadron, 31 Oct – 11 November 1941 (B-18 Bolo)

- 44th Bombardment Squadron (40th Bombardment Group) 1 April 1941 – 16 June 1942 (B-18 Bolo)

- 20th Troop Carrier Squadron (Panama Air Depot) June 1942 – July 1943 (C-47 Skytrain)

- 4th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (72d Reconnaissance Group) 27 October 1943 – 21 May 1945; 5 October 1945 – 20 August 1946

- Antilles Air Command, 1 Mar – 25 August 1946

- As: Antilles Air Division, 12 January 1948 – 22 January 1949

- 24th Composite Wing, 25 August 1946 – 28 June 1948

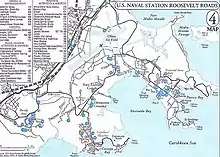

In 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered the construction of a naval base in the Atlantic similar to Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The site was meant to provide anchorage, docking, repair facilities, fuel, and supplies for 60% of the Atlantic Fleet. The naval base, which was named U.S. Naval Station Roosevelt Roads’ became the largest naval installation in the world in land mass and was meant to be the Pearl Harbor of the Atlantic, however with the defeat of Germany, the United States concentrated all of their efforts to the war in the Pacific. In May 2003, after six decades of existence, the base was officially shut down by the U.S. Navy.[38][39]

Highly decorated combatants

Three Puerto Ricans were awarded Distinguished Service Cross. The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is the second highest military decoration of the United States Army, awarded for extreme gallantry and risk of life in actual combat with an armed enemy force. The first Puerto Rican recipient of said award was PFC Joseph R. Martínez. He was followed by PFC. Luis F. Castro and Private Anibal Irrizarry.[40][41][42]

PFC Joseph (José) R. Martínez born in San Germán, Puerto Rico destroyed a German Infantry unit and tank in Tunis by providing heavy artillery fire, saving his platoon from being attacked in the process. He received the Distinguished Service Cross from General George S. Patton, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican recipient of said military decoration.[43] His citation reads as follow:

"The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Joseph R. Martinez, Private First Class, U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy in action against enemy forces in March 1943. Private First Class Martinez's intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army."[43]

Private First Class Luis F. Castro, born in Orocovis, Puerto Rico, was assigned to 47th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division. PFC. Castro's platoon was about to be overrun by enemy German forces, when he decided to stay in the rear flank and cover his men's retreat by providing firepower killing 15 of the enemy in the process.[44]

Private Anibal Irizarry born in Puerto Rico, was assigned to Co. L, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Regiment. Private Irizarry single-handedly destroyed two enemy machine gun nests and captured eight enemy soldiers.[45]

Agustín Ramos Calero was one of many Puerto Ricans who distinguished themselves in combat. Calero's company was in the vicinity of Colmar, France, and engaged in combat against a squad of German soldiers in what is known as the Battle of Colmar Pocket. Calero attacked the squad, killing ten of them and capturing 21 shortly before being wounded himself. Following these events, he was nicknamed "One-Man Army" by his comrades. A Silver Star was among the 22 decorations and medals which he was awarded from the US Army for his actions during World War II, thus becoming the most decorated Hispanic soldier in all of the United States during that war.[46]

United States Army Air Forces

Puerto Ricans also served in the United States Army Air Forces. In 1944, Puerto Rican aviators were sent to the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama to train the famed 99th Fighter Squadron of the Tuskegee Airmen. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American military aviators in the United States armed forces. Puerto Ricans were also involved in clerical positions with the Tuskegee unit. Among the Puerto Ricans who helped make the Tuskegee experiment a successful one were T/Sgt. Pablo Diaz Albortt, an NCO (Non Commissioned Officer) in charge of the Special Service Office, and Eugene Calderon, who was assigned to the "Red Tail" unit, as the Company Clerk.[47] By the end of the war, the Tuskegee Airmen were credited with 112 Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, a patrol boat run aground by machine-gun fire, and destruction of numerous fuel dumps, trucks and trains.[48]

Puerto Ricans distinguished themselves in aerial combat as well. This was the case of then-Captains Mihiel "Mike" Gilormini and Alberto A. Nido, Lieutenants José Antonio Muñiz and César Luis González and airman T/Sgt. Clement Resto.

Captain Mihiel "Mike" Gilormini served in the Royal Air Force and in the Army Air Force during World War II. He was a flight commander whose last combat mission was attacking the airfield at Milano, Italy. His last flight in Italy gave air cover for General George Marshall's visit to Pisa. He was the recipient of the Silver Star Medal, the Air Medal with four clusters, and the Distinguished Flying Cross 5 times. Gilormini later became the Founder of the Puerto Rico Air National Guard and retired as Brigadier General.

Captain Alberto A. Nido served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Royal Air Force and in the United States Army Air Forces during the war. He flew missions as a bomber pilot for the RCAF and as a Supermarine Spitfire fighter pilot for the RAF. As member of the RAF, he belonged to 67th Reconnaissance Squadron who participated in 275 combat missions. Nido later transferred to the USAAF's 67th Fighter Group as a P-51 Mustang fighter pilot. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters. Nido co-founded the Puerto Rico Air National Guard and, as Gilormini, retired a Brigadier General.[49]

Lieutenant José Antonio Muñiz served with distinction in the China-Burma-India Theater. During his tour of duty he flew 20 combat missions against the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force and shot down a Mitsubishi A6M Zero.[50] In 1960, Muñiz was flying a formation of F-86s celebrating the 4th of July festivities in Puerto Rico and upon take off his airplane flamed out and crashed. In 1963, the Air National Guard Base, at the San Juan International airport in Puerto Rico, was renamed "Muñiz Air National Guard Base" in his honor.[51]

2nd Lieutenant César Luis González, a co-pilot of a C-47, was the first Puerto Rican pilot in the United States Army Air Forces. He was one of the initial participants of the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943 also known as Operation Husky. During the invasion of Sicily, he flew on two night missions, the first on July 9, where his mission was to release paratroops of 82nd Airborne Division on the area of Gela and the second on July 11, when he dropped reinforcements in the area. His unit was awarded a "DUC" for carrying out this second mission in spite of bad weather and heavy attack by enemy ground and naval forces. González died on November 22, 1943, when his plane crashed during training off the end of the runway at Castelvetrano. He was posthumously promoted to First Lieutenant.[52]

T/Sgt. Clement Resto served with the 303rd Bomb Group and participated in numerous bombing raids over Germany. During a bombing mission over Düren, Germany, Resto's plane, a B-17 Flying Fortress, was shot down. He was captured by the Gestapo and sent to Stalag XVII-B where he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. Resto, who lost an eye during his last mission, was awarded a Purple Heart, a POW Medal, and an Air Medal with one battle star after he was liberated from captivity.[53][54]

In 1945, when Kwajalein of the Marshall Islands was secured by the U.S. forces, Sergeant Fernando Bernacett was among the Marines who were sent to guard various essential military installations. Bernacett, a combat veteran of the Battle of Midway, guarded the airport and prisoners of war as well as the atomic bomb as it made its way for Japan.[55]

Women in the military

When the United States entered World War II, Puerto Rican nurses volunteered for service but were not accepted into the Army or Navy Nurse Corps.

In 1944, the Army sent recruiters to the island to recruit no more than 200 women for the Women's Army Corps (WAC). Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit which was to be composed of only 200 women. The Puerto Rican WAC unit, Company 6, 2nd Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, a segregated Hispanic unit, was assigned to the New York Port of Embarkation, after their basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. They were assigned to work in military offices which planned the shipment of troops around the world.[56] Among them was PFC Carmen García Rosado, who in 2006, authored and published a book titled "LAS WACS-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra Mundial" (The WACs-The participation of the Puerto Rican women in the Second World War), the first book to document the experiences of the first 200 Puerto Rican women who participated in said conflict.[57]

That same year the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) decided to accept Puerto Rican nurses so that Army hospitals would not have to deal with the language barriers.[58] Thirteen women submitted applications, were interviewed, underwent physical examinations, and were accepted into the ANC. Eight of these nurses were assigned to the Army Post at San Juan, where they were valued for their bilingual abilities. Five nurses were assigned to work at the hospital at Camp Tortuguero, Puerto Rico. Among them was Second Lieutenant Carmen Lozano Dumler, who became one of the first Puerto Rican female military officers.[56]

Not all the women served as nurses: some women served in administrative duties in the mainland or near combat zones. Such was the case of Technician Fourth Grade Carmen Contreras-Bozak who belonged to the 149th Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. The 149th Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) Post Headquarters Company was the first WAAC Company to go overseas, setting sail from New York Harbor for Europe in January 1943. The unit arrived in Northern Africa on January 27, 1943 and rendered overseas duties in Algiers within General Dwight D. Eisenhower's theater headquarters, T/4. Carmen Contreras-Bozak, a member of this unit, was the first Hispanic to serve in the U.S. Women's Army Corps as an interpreter and in numerous administrative positions.[58][59]

Another was Lieutenant Junior Grade Maria Rodriguez Denton, the first woman from Puerto Rico who became an officer in the United States Navy as member of the WAVES. The Navy assigned LTJG Denton as a library assistant at the Cable and Censorship Office in New York City. It was LTJG Denton who forwarded the news (through channels) to President Harry S. Truman that the war had ended.[58]

Some Puerto Rican women became notable in other fields outside of the military. Among them Sylvia Rexach – a composer of boleros, Marie Teresa Rios – an author, and Julita Ross – singer.

Sylvia Rexach, dropped-out of the University of Puerto Rico in 1942 and joined the United States Army as a member of the WACS where she served as an office clerk. She served until 1945, when she was honorably discharged.[60] Marie Teresa Rios was a Puerto Rican writer who also served in World War II. Rios, mother of Medal of Honor recipient, Capt. Humbert Roque Versace and author of The Fifteenth Pelican which was the basis for the popular 1960s television sitcom "The Flying Nun", drove Army trucks and buses. She also served as a pilot for the Civil Air Patrol. Rios Versace wrote and edited for various newspapers around the world, including places such as Guam, Germany, Wisconsin, and South Dakota, and publications such the Armed Forces Star & Stripes and Gannett.[61] During World War II, Julita Ross entertained the troops with her voice in "USO shows" (United Service Organizations).[62]

Puerto Rican commanders

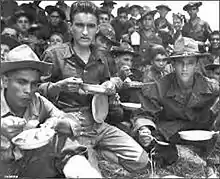

and Brigadier General del Valle, Corps Artillery Commander, examine a plaster relief map of Guam on board USS Appalachian

In addition to Lieutenant Colonel Juan Cesar Cordero Davila, nine Puerto Ricans who graduated from the United States Naval Academy and the United States Military Academy served in command positions in the Army, Navy, and the Marine Corps.[63] They were: Lieutenant General Pedro Augusto del Valle, USMC, the first Hispanic to reach the rank of General in the Marine Corps; Rear Admiral Frederick Lois Riefkohl, USN, the first Puerto Rican to graduate from the Naval Academy and recipient of the Navy Cross; Rear Admiral Jose M. Cabanillas, USN, who was the Executive Officer of USS Texas which participated in the invasions of North Africa and Normandy (D-Day); Rear Admiral Edmund Ernest Garcia, USN, commander of the destroyer USS Sloat who saw action in the invasions of Africa, Sicily, and France; Admiral Horacio Rivero Jr., USN, who was the first Hispanic to become a four-star Admiral; Captain Marion Frederic Ramirez de Arellano, USN, the first Hispanic submarine commander, who commanded USS Balao and is credited with sinking two Japanese ships; Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez, USN, a highly decorated submarine commander who was the recipient of two Silver Star Medals; Colonel Virgilio N. Cordero Jr., USA, recipient of three Silver Star Medals and a Bronze Star Medal, Battalion Commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment on December 8, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked the U.S. military installations in the Philippines. Colonel Virgil R. Miller, USA, Regimental Commander of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team; and Colonel Jaime Sabater Sr., USMC, Class of 1927.

- Lieutenant General Pedro del Valle, USMC, a highly decorated Marine, played a key role in the Guadalcanal Campaign and the Battle of Guam and became the Commanding General of the First Marine Division. Del Valle played an instrumental role in the defeat of the Japanese forces in Okinawa and was in charge of the reorganization of Okinawa.[64][65][66]

- Rear Admiral Frederick Lois Riefkohl, USN, was the captain of USS Vincennes, which was assigned to the Fire Support Group, LOVE (with Transport Group XRAY) under the command of Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner's Task Force TARE (Amphibious Force) during the landing in the Solomon Islands on August 7, 1942.[67]

- Prior to World War II, Rear Admiral Jose M. Cabanillas, USN, served aboard various cruisers, destroyers, and submarines. In 1942, upon the outbreak of World War II, he was assigned Executive Officer of USS Texas. Texas participated in the invasion of North Africa by destroying an ammunition dump near Port Lyautey. Cabanillas also participated in the invasion of Normandy on D-Day.[68]

- Rear Admiral Edmund Ernest García, USN, was the commander of the destroyer USS Sloat and saw action in the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, and France.[69]

- Admiral Horacio Rivero Jr., USN, served aboard USS San Juan (CL-54) and was involved in providing artillery cover for Marines landing on Guadalcanal, the Marshall Islands, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. For his service, he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Combat "V."

- Captain Marion Frederic Ramírez de Arellano, USN, the first Hispanic submarine commanding officer,[71] was a submarine commander in the Navy who was awarded two Silver Star Medals, the Legion of Merit, and a Bronze Star Medal for his actions against the Imperial Japanese Navy. Not only is he credited with the sinking of at least two Japanese ships, but he also led the rescue of the lives of numerous downed Navy pilots.[63]

- Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez, USN, who was at the time a Lieutenant Commander, saw action aboard submarines and on various occasions weathered depth charge attacks. For his actions, he was awarded the Silver and Bronze Star Medals. Benitez would later play an important role in the first American undersea spy mission of the Cold War as commander of the submarine USS Cochino in what became known as the "Cochino Incident".[72]

- Colonel Virgilio N. Cordero Jr., USA, was the Battalion Commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment on December 8, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked the U.S. military installations in the Philippines. The Bataan Defense Force surrendered on April 9, 1942 and Cordero and his men underwent brutal torture and humiliation during the Bataan Death March and nearly four years of captivity. Cordero was one of nearly 1,600 members of the 31st Infantry who were taken as prisoners. Half of these men perished while prisoners of the Japanese forces. Cordero gained his freedom when the Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1945, and he returned to the United States. Cordero, who retired with the rank of Brigadier General, wrote about his experiences as a prisoner of war and what he went through during the Bataan Death March. He authored My Experiences during the War with Japan, which was published in 1950. In 1957, he authored a revised Spanish version titled Bataan y la Marcha de la Muerte; Volume 7 of Colección Vida e Historia,[16]

- Colonel Virgil R. Miller, USA, born in San Germán, Puerto Rico, was the Regimental Commander of the 442d Regimental Combat Team, a unit which was composed of "Nisei" (second generation Americans of Japanese descent), during World War II. He led the 442nd in its rescue of the Lost Texas Battalion of the 36th Infantry Division, in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France.[73][74]

- Colonel Jaime Sabater Sr., USMC, commanded the 1st Battalion 9th Marines during the Bougainville amphibious operations.[75] Sabater also participated in the Battle of Guam (July 21, 1944- August 10, 1944) as Executive officer of the 9th Marines. He was wounded in action on July 21, 1944 and awarded the Purple Heart.[76]

Discrimination

During World War II, the United States Army was segregated. Puerto Ricans who resided on the mainland and who were fluent in English served alongside their "White" counterparts and "Black" Puerto Ricans were assigned to units made up mostly of African Americans. Puerto Ricans from the island served in Puerto Rico's segregated units, like the 65th Infantry and the Puerto Rico National Guard's 295th and 296th regiments. Racial discrimination practiced against Hispanic Americans, including Puerto Ricans on the United States' east coast and Mexican Americans in California and the Southwest, was widespread. Some Puerto Ricans who served in regular Army units were witnesses to the racial discrimination of the day.[77]

In an interview, PFC Raul Rios Rodriguez said that during his basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he had encountered a strict drill instructor who was particularly harsh on the Hispanic and black soldiers in his unit. He stated that he remains resentful of the discriminatory treatment that Latino and black soldiers received during basic training: "We were all soldiers; we were all risking our lives for the United States. That should have never been done, never."[78] Rios Rodriguez was shipped to Le Havre, France, assigned to guard bridges and supply depots in France and Germany with the 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division.[78]

Another soldier, PFC Felix López-Santos was drafted into the Army and sent to Fort Dix in New Jersey for training. López -Santos went to Milne Bay and then to the small island of Woodlark, both in New Guinea, where he was in the communications department using telephone wires to communicate to the troops during the war. In an interview, López-Santos stated that in North Carolina he witnessed some forms of racial discrimination, but never experienced it for himself. He stated: "I remember seeing some colored people refused service at a restaurant, I believe that I was not discriminated against because of my blue eyes and fair complexion."[79]

According to Carmen García Rosado, one of the hardships which Puerto Rican women in the military were subject to was the social and racial discrimination which at the time was rampant in the United States against the Latino community.[80]

Human experimentation

Puerto Rican soldiers were also subject to human experimentation by the United States Armed Forces. On Panama's San Jose Island, Puerto Rican soldiers were exposed to mustard gas to see if they reacted differently than their "white" counterparts.[81] According to Susan L. Smith of the University of Alberta, the researchers were searching for evidence of race-based differences in the responses of the human body to mustard gas exposure.[82]

Post World War II

The American participation in the Second World War came to an end in Europe on May 8, 1945 when the western Allies celebrated "V-E Day" (Victory in Europe Day) upon Germany's surrender, and in the Asian theater on August 14, 1945 "V-J Day" (Victory over Japan Day) when the Japanese surrendered by signing the Japanese Instrument of Surrender.

On October 27, 1945, the 65th Infantry, which had participated in the battles of Naples–Fogis, Rome–Arno, central Europe, and of the Rhineland, sailed home from France. Arriving at Puerto Rico on November 9, 1945, they were received by the local population as national heroes and given a victorious reception at the Military Terminal of Camp Buchanan.

According to the book "Historia Militar De Puerto Rico" (Military history of Puerto Rico), by historian Col. Hector Andres Negroni, the men of the 65th Infantry were awarded the following military decorations:[83]

| Award | Name | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Star | 2 | |

| Bronze Star | 22 | |

| Purple Heart | 90 | |

The 295th Regiment returned on February 20, 1946 from the Panama Canal Zone, and the 296th Regiment on March 6. Both regiments were awarded the American Theatre streamer and the Pacific Theatre streamer. They were inactivated that same year.[84]

Many of the men and women who were discharged after the war returned to their civilian jobs or made use of the educational benefits of the G.I. Bill. Others, such as Major General Juan César Cordero Dávila, Colonel Carlos Betances Ramírez, Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero, and Master Sergeant Pedro Rodriguez, continued in the military as career soldiers and went on to serve in the Korean War.[85]

Some of the Puerto Ricans from the mainland who had not completed their full active duty in the military service were reassigned to the 65th Infantry in Puerto Rico. According to remarks made by Frank Bonilla in an interview, he discovered that there was a divide among the soldiers. The Puerto Ricans who had emigrated to the mainland were seen as "American Joes" while Puerto Ricans from the island considered themselves "pure" Puerto Ricans. Bonilla at first thought the soldiers were being disrespectful to the United States, especially since they stood at attention whenever "La Borinqueña", the Puerto Rican anthem, was played and not when the United States anthem. Bonilla is quoted as saying:

The Puerto Rican soldiers paid little, if any, attention to the playing of the 'Star Spangled Banner" "The soldiers in the regiment, although proud to be U.S. citizens, felt that they were a Puerto Rican army, not a US army," Mr. Bonilla said. "These men had a select unit pride because they had had more time overseas and in combat areas than the American units.[86]

Bonilla eventually earned a Ph.D. from Harvard and held faculty appointments at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, and the City University of New York. He became a major leader in Puerto Rican studies.[86]

According to the 4th Report of the Director of Selective Service of 1948, a total of 51,438 Puerto Ricans served in the Armed Forces during World War II, however the Department of Defense in its report titled "Number of Puerto Ricans serving in the U.S. Armed Forces during National Emergencies" stated that the total of Puerto Ricans who served was 65,034 and from that total 2,560 were listed as wounded.[87] These numbers only reflect those who served in Puerto Rican units. However, the total number of Puerto Ricans who served in World War II in other units cannot be determined because the military categorized Hispanics along with whites. The only racial groups for which separate statistics were kept were Blacks and Asians.[6][88]

The names of the 37 men who are known to have perished in the conflict are engraved in "El Monumento de la Recordación" (Memorial Monument) monument which honors the memory of those who have fallen in the defense of the United States. The monument is located in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[89]

Gallery of people

Carmen Dumler

Carmen Dumler Pedro de Valle

Pedro de Valle Carmen Conteras-Bozak

Carmen Conteras-Bozak César Luis González

César Luis González Joseph B. Aviles Sr.

Joseph B. Aviles Sr. Jose M. Cabanillas

Jose M. Cabanillas Carmen Garcia Rosado

Carmen Garcia Rosado Gilberto José Marxuach

Gilberto José Marxuach Virgil R. Miller

Virgil R. Miller Alberto A. Nido

Alberto A. Nido Rafael Celestino Benítez

Rafael Celestino Benítez.jpg.webp) Edmund Ernest García

Edmund Ernest García Horacio Rivero Jr.

Horacio Rivero Jr. Maria Rodriguez Denton

Maria Rodriguez Denton Fernando Bernacett

Fernando Bernacett

Further reading

- "Puertorriquenos Who Served With Guts, Glory, and Honor. Fighting to Defend a Nation Not Completely Their Own"; by : Greg Boudonck; ISBN 978-1497421837

- "Historia militar de Puerto Rico"; by: Hector Andres Negroni; publisher=Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario (1992); ISBN 84-7844-138-7

- 65th Infantry Division. Turner Publishing. 1997. ISBN 1-56311-118-7.

- del Valle, Pedro (1976). Semper fidelis: An autobiography. Christian Book Club of America. ASIN B0006COTKO.

- Esteves, General Luis Raúl (1955). ¡Los Soldados Son Así!. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Star Publishing Co. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- Gordy, Bill (1945). Right to be proud: History of the 65th infantry division's march across Germany. J. Wimmer. ASIN B0007J8K74.

- Lederer, Commander William J., USN (1950). The Last Cruise: The Story of the Sinking of the Submarine, U.S.S. Cochino. Sloane. ASIN B0007E631Y.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Hispanics in the Defense of America". America USA. 1996–2007. Archived from the original on 2007-04-11. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- Stetson Conn; Rose C. Engelman & Byron Fairchild (2000) [1964]. Guarding the United States and Its Outposts. U.S. Army in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 4-2. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "U.S. Latino and Latina World War II Oral History Project". University of Texas at Austin. 1990–2007. Archived from the original on 2007-12-08. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Hispanic Americans in the U.S. Army". United States Army.

- "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial"; by: Carmen García Rosado; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Regitro tro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685

See also

- Military history of Puerto Rico

- History of Puerto Ricans

- Camp Las Casas

- Puerto Rican Campaign

- Puerto Ricans in World War I

- Puerto Ricans in the Vietnam War

- 65th Infantry Regiment in the Korean War

- Puerto Rican women in the military

- List of Puerto Rican military personnel

- Borinqueneers Congressional Gold Medal

Notes

References

- "Donan bandera nazi a la Guardia Nacional de Puerto Rico". NotiCel (in Spanish). January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity; By Nancy Morris

- Dept. of Defense; "Number of Puerto Ricans in the U.S. Armed Forces during National Emergencies"

- "Introduction: World War II (1941–1945)". Hispanics in the Defense of America. Hispanic America USA. Archived from the original on 2007-02-04. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- Conn, Stetson; Engelman, Rose C. & Byron Fairchild (1961). "The Caribbean in Wartime". U.S. Army in World War II: Guarding the United States and Its Outposts. United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- "World War II By The Numbers". The National World War II Museum (New Orleans, LA). Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- Latinos who fought in Spain, Retrieved November 12, 2007

- "Richard A. H. Robinson. The Origins of Franco’s Spain – The Right, the Republic and Revolution, 1931–1936. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970) p. 28", Retrieved November 12, 2007

- Battle for Spain, Retrieved November 12, 2007

- U.S. citizens who fought against fascism Archived 2004-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved November 12, 2007

- Marin, Hector. "Puerto Rican Units (WWII)". Hispanics in the Defense of America. Hispanic America USA. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Puerto Rican Military History". El Boricua. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Ruiz, Bruce C. (November 1, 2002). "Major General Luis Raúl Esteves Völckers". bruceruiz.net. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- Boxing: Fatalities in Hawaii, December 7, 1941

- PBS – New York goes to War

- Toledo Blade – Jun 9, 1980

- "31st Infantry Regiment Association". Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- Bataan Death March

- United States War Department, History of the 762nd Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion; 15 September 1943 to 31 May 1945; Former designation 72d Coast Artillery Regiment; Fort Randolph, Canal Zone; Prepared at Inglewood, California and dated 31 May 1945; Available from the National Archives and Records Administration, Maryland.

- United States War Department; History of the 891st Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion; 15 September 1943 to 28 February 1945; Former designation First Battalion, 615th CA (AA). Fort Clayton, Canal Zone; Prepared at Inglewood, California and dated 31 May 1945; Available from the National Archives and Records Administration, Maryland.

- Key, Mervin. "A Short Biography of Carlos Betances-Ramirez". mervino.com. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- Commands

- "Biografías" (in Spanish). Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular.

- Francisco José Correa Bustamante (1995). Daniel Santos: Su vida y sus canciones. Guayaquil, Ecuador: Editores Corsan. pp. 25–51.

- "Military History". American Veteran's Committee for Puerto Rico Self-Determination. Archived from the original on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Villahermosa, LTC Gilberto (September 2000). "World War II". "Honor and Fidelity" – The 65th Infantry Regiment in Korea 1950–1954 (Official Army Report on the 65th Infantry Regiment). United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Harris, W.W. (2001). Puerto Rico's Fighting 65th U.S. Infantry:From San Juan to Chowon. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-056-2.

- Villahermosa, Colonel Gilberto (2000). "Juan Cesar Cordero-Davila". valerosos. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Shelby, Stanton (1984). World War II Order of Battle. New York: Galahad Books.

- "Gilberto Marxauch Acosta"; El Mundo; by: Luis O'Niel de Milan; June 7, 1957

- "Frank Bonilla". U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- De La Cruz, Juan. "Combat engineer Fernando Pagan went from Normandy to Belgium and Germany, where a sniper nearly killed him". U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Jennifer Nalewicki. "Louis Ramirez recalls brutality of war; but what still shines through is the camaraderie". U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-11. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Oral History Project Unanue Archived 2008-08-02 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved July 17, 2008

- Chris Nay. "Santos Deliz". U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- site United States Coast Guard

- Ravenstein, Charles A. Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History 1984. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- Puerto Rico Herald May 1, 2003 Archived October 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Navy Closes Major Base in Wake of Protests

- "Irizarry's DSC Citation". Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- "Martinez's DSC Citation". Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- Castro's DSC Citation

- "Martinez's DSC Citation". Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- "El Imparcial" – "Boricua mata 15 Alemanes"; Recobe Alta Condecoracion; November 13, 1945

- The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical; By Carmen Teresa Whalen and Víctor Vázquez; p. 78; Published 2005 by Temple University Press; ISBN 1-59213-413-0

- "Who was Agustín Ramos Calero?" (PDF). The Puerto Rican Soldier. August 17, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ”The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men who Changed a Nation”; By: Charles E. Francis, p. 370; Branden Books, 1997; ISBN 0828320292, 978-0828320290

- History of the Tuskegee Airmen

- El Mundo; "La carrera de Alberto A. Nido en las fuerzas aéreas de los EE. UU.; April 26, 1944; Number 9986

- "Relatan hechos en que Participaron"; El Mundo; May 12, 1945; Number 10467

- Muñiz Air National Guard Base

- Roll of Honor of the 314th Troop Carrier Group Archived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Memories of a Jug Driver". worldwar2pilots.com. Archived from the original on 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "T/Sgt. Clement Resto". valerosos.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-25. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- White, Jenny. "Fernando Bernacett". Latinos and Latinas in WW II. Archived from the original on 2008-04-23.

- Puerto Rican Woman in Defense of our country Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; page 60; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Regitro tro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- Bellafaire, Judith. "Puerto Rican Servicewomen in Defense of the Nation". Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- Kennon, Katie. "Young woman's life defined by service in Women's Army Corps". US Latinos and Latinas & World War II. Archived from the original on 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- Music of Puerto Rico

- Marie Teresa Rios

- Popular Culture

- "CAPT Marion Frederic Ramirez de Arellano". USNA graduates of Hispanic descent for the Class of 1911, 1915, 1924, 1927, 1931, 1935, 1939, 1943, 1947. Association of Naval Services Officers. February 27, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- Sontag, Blind Man's Bluff.

- "Puerto Rico Archives". Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Lieutenant General Pedro A. Del Valle, USMC". Who's Who in Marine Corps History. History Division, United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- Lippman, David H. "August 5th, 1942 – August 8th, 1942". World War II Plus 55. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Cabanillas, Jose C. (December 2001). "Mail Call" (PDF). Griggs-Grundy News. 2 (4): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-04.

- "USS Sloat (DE-245)". Navsource Online: Destroyer Escort Photo Archive.

- "The Submarine Forces Diversity Trailblazer – Capt. Marion Frederick Ramirez de Arellano"; Summer 2007 Undersea Warfare magazine; pg.31

- Sontag, Sherry; Christopher Drew; Annette Lawrence Drew (1998). Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage. Public Affairs. ISBN 0-06-097771-X.

- "Collection of the U.S. Military Academy Library" (PDF). Assembly. Summer 1969. pp. 132–133. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08.

- Shenkle, Kathryn. "Patriots under Fire: Japanese Americans in World War II". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17.

- Rentz, John N. (April 9, 2007) [1946]. "Appendix X: Commands and Staff". Bougainville and the Northern Solomons. USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Branch, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- Lodge, O.R. (1954). "Appendix IV: Command and Staff List of Major Units". The Recapture of Guam. Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- "Discrimination". History.com. Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- D'Arcy Kerschen. "Despite war's end and brother's horror stories, man was intent on joining military". Utopia: U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- de la Cruz, Juan. "Man survived jungle fever, suicide attacks and kangaroos during service in Pacific". Utopia: U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WWII Oral History Project. University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; Page 79; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Regitro tro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685

- The Panama News Archived September 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- The New York Academy of Medicine; The Lilianna Sauter Lecture; "Medicine in Wartime, Part IV: Place, Health and War: World War II Mustard Gas Experiments in Transnational Perspective"; Susan L. Smith, University of Alberta Archived November 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Negroni, Héctor Andrés (1992). Historia militar de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario. ISBN 978-84-7844-138-9.

- "The Puerto Rican Soldier". El Pozo Productions. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-02-10. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Puerto Rico Profile: The 65th Infantry Regiment in Korea". Puerto Rico Herald. June 30, 2000. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Quach, Anne. "Frank Bonilla became major figure in Puerto Rican studies". Utopia: U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WWII Oral History Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Department of Defense; "Number of Puerto Ricans serving in the U.S. Armed Forces during National Emergencies"

- "Minority Groups in World War II". United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "Monumento de la Recordación". Searching For Our Roots. February 10, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2007-03-18.