Quantum memory

In quantum computing, quantum memory is the quantum-mechanical version of ordinary computer memory. Whereas ordinary memory stores information as binary states (represented by "1"s and "0"s), quantum memory stores a quantum state for later retrieval. These states hold useful computational information known as qubits. Unlike the classical memory of everyday computers, the states stored in quantum memory can be in a quantum superposition, giving much more practical flexibility in quantum algorithms than classical information storage.

|

Units of information |

| Information-theoretic |

|---|

| Data storage |

| Quantum information |

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

Quantum memory is essential for the development of many devices in quantum information processing, including a synchronization tool that can match the various processes in a quantum computer, a quantum gate that maintains the identity of any state, and a mechanism for converting predetermined photons into on-demand photons. Quantum memory can be used in many aspects, such as quantum computing and quantum communication. Continuous research and experiments have enabled quantum memory to realize the storage of qubits.[1]

Background and history

The interaction of quantum radiation with multiple particles has sparked scientific interest over the past decade. Quantum memory is one such field, mapping the quantum state of light onto a group of atoms and then restoring it to its original shape. Quantum memory is a key element in information processing, such as optical quantum computing and quantum communication, while opening a new way for the foundation of light-atom interaction. However, restoring the quantum state of light is no easy task. While impressive progress has been made, researchers are still working to make it happen.[2]

Quantum memory based on the quantum exchange to store photon qubits has been demonstrated to be possible. Kessel and Moiseev[3] discussed quantum storage in the single photon state in 1993. The experiment was analyzed in 1998 and demonstrated in 2003. In summary, the study of quantum storage in the single photon state can be regarded as the product of the classical optical data storage technology proposed in 1979 and 1982, an idea inspired by the high density of data storage in the mid-1970s. Optical data storage can be achieved by using absorbers to absorb different frequencies of light, which are then directed to beam space points and stored.

Types

Atomic Gas Quantum Memory

Normal, classical optical signals are transmitted by varying the amplitude of light. In this case, a piece of paper, or a computer hard disk, can be used to store information on the lamp. In the quantum information scenario, however, the information may be encoded according to the amplitude and phase of the light. For some signals, you cannot measure both the amplitude and phase of the light without interfering with the signal. To store quantum information, light itself needs to be stored without being measured. An atomic gas quantum memory is recording the state of light into the atomic cloud. When light's information is stored by atoms, relative amplitude and phase of light is mapped to atoms and can be retrieved on-demand.[4]

Solid Quantum Memory

In classical computing, memory is a trivial resource that can be replicated in long-lived memory hardware and retrieved later for further processing. In quantum computing, this is forbidden because, according to the no clone theorem, any quantum state cannot be reproduced completely. Therefore, in the absence of quantum error correction, the storage of qubits is limited by the internal coherence time of the physical qubits holding the information. "Quantum memory" beyond the given physical qubit storage limits will be a quantum information transmission to "storing qubits" not easily affected by environmental noise and other factors. The information would later be transferred back to the preferred "process qubits" to allow rapid operations or reads.[5]

Discovery

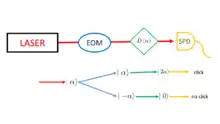

Optical quantum memory is usually used to detect and store single photon quantum states. However, producing efficient memory of this kind is still a huge challenge for current science. A single photon is so low in energy as to be lost in a complex light background. These problems have long kept quantum storage rates below 50%. A team led by professor Du Shengwang of the department of physics at the Hong Kong University of science and technology[6] and William Mong Institute of Nano Science and Technology at HKUST[7] has found a way to increase the efficiency of optical quantum memory to more than 85 percent. The discovery also brings the popularity of quantum computers closer to reality. At the same time, the quantum memory can also be used as a repeater in the quantum network, which lays the foundation for the quantum Internet.

Research and application

Quantum memory is an important component of quantum information processing applications such as quantum network, quantum repeater, linear optical quantum computation or long-distance quantum communication.[8]

Optical data storage has been an important research topic for many years. Its most interesting function is the use of the laws of quantum physics to protect data from theft, through quantum computing and quantum cryptography unconditionally guaranteed communication security.[9]

They allow particles to be superimposed and in a superposition state, which means they can represent multiple combinations at the same time. These particles are called quantum bits, or qubits. From a cybersecurity perspective, the magic of qubits is that if a hacker tries to observe them in transit, their fragile quantum states shatter. This means it is impossible for hackers to tamper with network data without leaving a trace. Now, many companies are taking advantage of this feature to create networks that transmit highly sensitive data. In theory, these networks are secure.[10]

Microwave storage and light learning microwave conversion

The nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond has attracted a lot of research in the past decade due to its excellent performance in optical nanophotonic devices. In a recent experiment, electromagnetically induced transparency was implemented on a multi-pass diamond chip to achieve full photoelectric magnetic field sensing. Despite these closely related experiments, optical storage has yet to be implemented in practice. The existing nitrogen-vacancy center (negative charge and neutral nitrogen-vacancy center) energy level structure makes the optical storage of the diamond nitrogen-vacancy center possible.

The coupling between the nitrogen-vacancy spin ensemble and superconducting qubits provides the possibility for microwave storage of superconducting qubits. Optical storage combines the coupling of electron spin state and superconducting quantum bits, which enables the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond to play a role in the hybrid quantum system of the mutual conversion of coherent light and microwave.[11]

Orbital angular momentum is stored in alkali vapor

Large resonant light depth is the premise of constructing efficient quantum-optical memory. Alkali metal vapor isotopes of a large number of near-infrared wavelength optical depth, because they are relatively narrow spectrum line and the number of high density in the warm temperature of 50-100 ∘ C. Alkali vapors have been used in some of the most important memory developments, from early research to the latest results we are discussing, due to their high optical depth, long coherent time and easy near-infrared optical transition.

Because of its high information transmission ability, people are more and more interested in its application in the field of quantum information. Structured light can carry orbital angular momentum, which must be stored in the memory to faithfully reproduce the stored structural photons. An atomic vapor quantum memory is ideal for storing such beams because the orbital angular momentum of photons can be mapped to the phase and amplitude of the distributed integration excitation. Diffusion is a major limitation of this technique because the motion of hot atoms destroys the spatial coherence of the storage excitation. Early successes included storing weakly coherent pulses of spatial structure in a warm, ultracold atomic whole. In one experiment, the same group of scientists in a caesium magneto-optical trap was able to store and retrieve vector beams at the single-photon level.[12] The memory preserves the rotation invariance of the vector beam, making it possible to use it in conjunction with qubits encoded for maladjusted immune quantum communication.

The first storage structure, a real single photon, was achieved with electromagnetically induced transparency in rubidium magneto-optical trap. The predicted single photon generated by spontaneous four-wave mixing in one magneto-optical trap is prepared by an orbital angular momentum unit using spiral phase plates, stored in the second magneto-optical trap and recovered. The dual-orbit setup also proves coherence in multimode memory, where a preannounced single photon stores the orbital angular momentum superposition state for 100 nanoseconds.[11]

GEM

GEM (Gradient Echo Memory) is a protocol for storing optical information and it can be applied to both atomic gas and solid-state memories. The idea was first demonstrated by researchers at ANU. The experiment in a three-level system based on hot atomic vapor resulted in demonstration of coherent storage with efficiency up to 87%.[13]

Electromagnetically induced transparency

Electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) was first introduced by Harris and his colleagues at Stanford University in 1990.[14] The work showed that when a laser beam causes a quantum interference between the excitation paths, the optical response of the atomic medium is modified to eliminate absorption and refraction at the resonant frequencies of atomic transitions. Slow light, optical storage, and quantum memories can be achieved based on EIT. In contrast to other approaches, EIT has a long storage time and is a relatively easy and inexpensive solution to implement. For example, electromagnetically induced transparency does not require the very high power control beams usually needed for Raman quantum memories, nor does it require the use of liquid helium temperatures. In addition, photon echo can read EIT while the spin coherence survives due to the time delay of readout pulse caused by a spin recovery in non-uniformly broadened media. Although there are some limitations on operating wavelength, bandwidth, and mode capacity, techniques have been developed to make EIT-based quantum memories a valuable tool in the development of quantum telecommunication systems.[11] In 2018, a highly efficient EIT-based optical memory in cold atom demonstrated a 92% storage-and-retrieval efficiency in the classical regime with coherent beams [15] and a 70% storage-and-retrieval efficiency was demonstrated for polarization qubits encoded in weak coherent states, beating any classical benchmark.[16] Following these demonstrations, single-photon polarization qubits were then stored via EIT in a 85Rb cold atomic ensemble and retrieved with an 85% efficiency [17] and entanglement between two cesium-based quantum memories was also achieved with an overall transfer efficiency close to 90%.[18]

Crystals doped with rare earth

The mutual transformation of quantum information between light and matter is the focus of quantum informatics. The interaction between a single photon and a cooled crystal doped with rare earth ions is investigated. Crystals doped with rare earth have broad application prospects in the field of quantum storage because they provide a unique application system.[19] Li Chengfeng from the quantum information laboratory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences developed a solid-state quantum memory and demonstrated the photon computing function using time and frequency. Based on this research, a large-scale quantum network based on quantum repeater can be constructed by utilizing the storage and coherence of quantum states in the material system. Researchers have shown for the first time in rare-earth ion-doped crystals. By combining the three-dimensional space with two-dimensional time and two-dimensional spectrum, a kind of memory that is different from the general one is created. It has the multimode capacity and can also be used as a high fidelity quantum converter. Experimental results show that in all these operations, the fidelity of the three-dimensional quantum state carried by the photon can be maintained at around 89%.[20]

Raman scattering in solids

Diamond has very high Raman gain in optical phonon mode of 40 THz and has a wide transient window in a visible and near-infrared band, which makes it suitable for being an optical memory with a very wide band. After the Raman storage interaction, the optical phonon decays into a pair of photons through the channel, and the decay lifetime is 3.5 ps, which makes the diamond memory unsuitable for communication protocol.

Nevertheless, diamond memory has allowed some revealing studies of the interactions between light and matter at the quantum level: optical phonons in a diamond can be used to demonstrate emission quantum memory, macroscopic entanglement, pre-predicted single-photon storage, and single-photon frequency manipulation.[11]

Future development

For quantum memory, quantum communication and cryptography are the future research directions. However, there are many challenges to building a global quantum network. One of the most important challenges is to create memories that can store the quantum information carried by light. Researchers at the University of Geneva in Switzerland working with France's CNRS have discovered a new material in which an element called ytterbium can store and protect quantum information, even at high frequencies. This makes ytterbium an ideal candidate for future quantum networks. Because signals cannot be replicated, scientists are now studying how quantum memories can be made to travel farther and farther by capturing photons to synchronize them. In order to do this, it becomes important to find the right materials for making quantum memories. Ytterbium is a good insulator and works at high frequencies so that photons can be stored and quickly restored.

References

- Lvovsky AI, Sanders BC, Tittel W (December 2009). "Optical quantum memory". Nature Photonics. 3 (12): 706–714. Bibcode:2009NaPho...3..706L. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2009.231. ISSN 1749-4893. S2CID 4661175.

- Le Gouët JL, Moiseev S (2012). "Quantum Memory". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 45 (12): 120201. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/45/12/120201.

- Ohlsson N, Kröll S, Moiseev SA (2003). "Delayed single-photon self-interference — A double slit experiment in the time domain". In Bigelow NP, Eberly JH, Stroud CR, Walmsley IA (eds.). Coherence and Quantum Optics VIII. Springer US. pp. 383–384. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8907-9_80. ISBN 9781441989079.

- Hosseini M, Sparkes B, Hétet G, et al. (2009). "Coherent optical pulse sequencer for quantum applications". Nature. 461 (7261): 241–245. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..241H. doi:10.1038/nature08325. PMID 19741705. S2CID 1077208.

- Freer S, Simmons S, Laucht A, Muhonen JT, Dehollain JP, Kalra R, et al. (2016). "A single-atom quantum memory in silicon". Quantum Science and Technology. 2: 015009. arXiv:1608.07109. doi:10.1088/2058-9565/aa63a4. S2CID 118590076.

- "Shengwang Du Group | Atom and Quantum Optics Lab". Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- "RC02_William Mong Institute of Nano Science and Technology | Institutes and Centers | Research Institutes and Centers | Research | HKUST Department of Physics". physics.ust.hk. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- "Quantum memories [GAP-Optique]". www.unige.ch. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Tittel W, Afzelius M, Chaneliere T, Cone RL, Kröll S, Moiseev SA, Sellars M (2010). "Photon-echo quantum memory in solid state systems". Laser & Photonics Reviews. 4 (2): 244–267. Bibcode:2010LPRv....4..244T. doi:10.1002/lpor.200810056. ISSN 1863-8899. S2CID 120294578.

- "Quantum Communication | PicoQuant". www.picoquant.com. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Heshami K, England DG, Humphreys PC, Bustard PJ, Acosta VM, Nunn J, Sussman BJ (November 2016). "Quantum memories: emerging applications and recent advances". Journal of Modern Optics. 63 (20): 2005–2028. doi:10.1080/09500340.2016.1148212. PMC 5020357. PMID 27695198.

- Nicolas A, Veissier L, Giner L, Giacobino E, Maxein D, Laurat J (March 2014). "A quantum memory for orbital angular momentum photonic qubits". Nature Photonics. 8 (3): 234–238. arXiv:1308.0238. Bibcode:2014NaPho...8..234N. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2013.355. S2CID 118585951.

- Hosseini M, Sparkes B, Campbell G, et al. (2011). "High efficiency coherent optical memory with warm rubidium vapour". Nat Commun. 2: 174. arXiv:1009.0567. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..174H. doi:10.1038/ncomms1175. PMC 3105315. PMID 21285952. S2CID 6545778.

- Harris SE, Field JE, Imamoglu A (March 1990). "Nonlinear optical processes using electromagnetically induced transparency". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 64 (10): 1107–1110. Bibcode:1990PhRvL..64.1107H. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.64.1107. PMID 10041301.

- Hsiao YF, Tsai PJ, Chen HS, Lin SX, Hung CC, Lee CH, et al. (May 2018). "Highly Efficient Coherent Optical Memory Based on Electromagnetically Induced Transparency". Physical Review Letters. 120 (18): 183602. arXiv:1605.08519. Bibcode:2018PhRvL.120r3602H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.183602. PMID 29775362. S2CID 21741318.

- Vernaz-Gris P, Huang K, Cao M, Sheremet AS, Laurat J (January 2018). "Highly-efficient quantum memory for polarization qubits in a spatially-multiplexed cold atomic ensemble". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 363. arXiv:1707.09372. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..363V. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02775-8. PMC 5785556. PMID 29371593.

- Wang Y, Li J, Zhang S, Su K, Zhou Y, Liao K, Du S, Yan H, Zhu SL (March 2019). "Efficient quantum memory for single-photon polarization qubits". Nature Photonics. 13 (5): 346–351. arXiv:2004.03123. Bibcode:2019NaPho..13..346W. doi:10.1038/s41566-019-0368-8. S2CID 126945158.

- Cao M, Hoffet F, Qiu S, Sheremet AS, Laurat J (2020-10-20). "Efficient reversible entanglement transfer between light and quantum memories". Optica. 7 (10): 1440–1444. arXiv:2007.00022. Bibcode:2020Optic...7.1440C. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.400695.

- "Solid State Quantum Memories | QPSA @ ICFO". qpsa.icfo.es. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Simon C, Afzelius M, Appel J, de la Giroday AB, Dewhurst SJ, Gisin N, Hu CY, Jelezko F, Kröll S (2010-05-01). "Quantum memories". The European Physical Journal D. 58 (1): 1–22. arXiv:1003.1107. doi:10.1140/epjd/e2010-00103-y. ISSN 1434-6079. S2CID 11793247.