Entanglement distillation

Entanglement distillation (also called entanglement purification) is the transformation of N copies of an arbitrary entangled state into some number of approximately pure Bell pairs, using only local operations and classical communication.

Quantum entanglement distillation can in this way overcome the degenerative influence of noisy quantum channels[1] by transforming previously shared less entangled pairs into a smaller number of maximally entangled pairs.

History

The limits for entanglement dilution and distillation are due to C. H. Bennett, H. Bernstein, S. Popescu, and B. Schumacher,[2] who presented the first distillation protocols for pure states in 1996; entanglement distillation protocols for mixed states were introduced by Bennett, Brassard, Popescu, Schumacher, Smolin and Wootters[3] the same year. Bennett, DiVincenzo, Smolin and Wootters[1] established the connection to quantum error-correction in a ground-breaking paper published in August 1996, also in the journal of Physical Review, which has stimulated a lot of subsequent research.

Quantifying entanglement

A two qubit system can be written as a superposition of possible computational basis qubit states: , each with an associated complex coefficient :

As in the case of a single qubit, the probability of measuring a particular computational basis state is the square of the modulus of its amplitude, or associated coefficient, , subject to the normalization condition . The normalization condition guarantees that the sum of the probabilities add up to 1, meaning that upon measurement, one of the states will be observed.

The Bell state is a particularly important example of a two qubit state:

Bell states possess the property that measurement outcomes on the two qubits are correlated. As can be seen from the expression above, the two possible measurement outcomes are zero and one, both with probability of 50%. As a result, a measurement of the second qubit always gives the same result as the measurement of the first qubit.

Bell states can be used to quantify entanglement. Let m be the number of high-fidelity copies of a Bell state that can be produced using local operations and classical communication (LOCC). Given a large number of Bell states the amount of entanglement present in a pure state can then be defined as the ratio of , called the distillable entanglement of a particular state , which gives a quantified measure of the amount of entanglement present in a given system. The process of entanglement distillation aims to saturate this limiting ratio. The number of copies of a pure state that may be converted into a maximally entangled state is equal to the von Neumann entropy of the state, which is an extension of the concept of classical entropy for quantum systems. Mathematically, for a given density matrix , the von Neumann entropy is . Entanglement can then be quantified as the entropy of entanglement, which is the von Neumann entropy of either or as:

Which ranges from 0 for a product state to for a maximally entangled state (if the is replaced by then maximally entangled has a value of 1).

Motivation

Suppose that two parties, Alice and Bob, would like to communicate classical information over a noisy quantum channel. Either classical or quantum information can be transmitted over a quantum channel by encoding the information in a quantum state. With this knowledge, Alice encodes the classical information that she intends to send to Bob in a (quantum) product state, as a tensor product of reduced density matrices where each is diagonal and can only be used as a one time input for a particular channel .

The fidelity of the noisy quantum channel is a measure of how closely the output of a quantum channel resembles the input, and is therefore a measure of how well a quantum channel preserves information. If a pure state is sent into a quantum channel emerges as the state represented by density matrix , the fidelity of transmission is defined as .

The problem that Alice and Bob now face is that quantum communication over large distances depends upon successful distribution of highly entangled quantum states, and due to unavoidable noise in quantum communication channels, the quality of entangled states generally decreases exponentially with channel length as a function of the fidelity of the channel. Entanglement distillation addresses this problem of maintaining a high degree of entanglement between distributed quantum states by transforming N copies of an arbitrary entangled state into approximately Bell pairs, using only local operations and classical communication. The objective is to share strongly correlated qubits between distant parties (Alice and Bob) in order to allow reliable quantum teleportation or quantum cryptography.

Entanglement concentration

Pure states

Given n particles in the singlet state shared between Alice and Bob, local actions and classical communication will suffice to prepare m arbitrarily good copies of with a yield

Let an entangled state have a Schmidt decomposition:

where coefficients p(x) form a probability distribution, and thus are positive valued and sum to unity. The tensor product of this state is then,

Now, omitting all terms which are not part of any sequence which is likely to occur with high probability, known as the typical set: the new state is

And renormalizing,

Then the fidelity

Suppose that Alice and Bob are in possession of m copies of . Alice can perform a measurement onto the typical set subset of , converting the state with high fidelity. The theorem of typical sequences then shows us that is the probability that the given sequence is part of the typical set, and may be made arbitrarily close to 1 for sufficiently large m, and therefore the Schmidt coefficients of the renormalized Bell state will be at most a factor larger. Alice and Bob can now obtain a smaller set of n Bell states by performing LOCC on the state with which they can overcome the noise of a quantum channel to communicate successfully.

Mixed states

Many techniques have been developed for doing entanglement distillation for mixed states, giving a lower bounds on the value of the distillable entanglement for specific classes of states .

One common method involves Alice not using the noisy channel to transmit source states directly but instead preparing a large number of Bell states, sending half of each Bell pair to Bob. The result from transmission through the noisy channel is to create the mixed entangled state , so that Alice and Bob end up sharing copies of . Alice and Bob then perform entanglement distillation, producing almost perfectly entangled states from the mixed entangled states by performing local unitary operations and measurements on the shared entangled pairs, coordinating their actions through classical messages, and sacrificing some of the entangled pairs to increase the purity of the remaining ones. Alice can now prepare an qubit state and teleport it to Bob using the Bell pairs which they share with high fidelity. What Alice and Bob have then effectively accomplished is having simulated a noiseless quantum channel using a noisy one, with the aid of local actions and classical communication.

Let be a general mixed state of two spin-1/2 particles which could have resulted from the transmission of an initially pure singlet state

through a noisy channel between Alice and Bob, which will be used to distill some pure entanglement. The fidelity of M

is a convenient expression of its purity relative to a perfect singlet. Suppose that M is already a pure state of two particles for some . The entanglement for , as already established, is the von Neumann entropy where

and likewise for , represent the reduced density matrices for either particle. The following protocol is then used:[3]

- Performing a random bilateral rotation on each shared pair, choosing a random SU(2) rotation independently for each pair and applying it locally to both members of the pair transforms the initial general two-spin mixed state M into a rotationally symmetric mixture of the singlet state and the three triplet states and : The Werner state has the same purity F as the initial mixed state M from which it was derived due to the singlet's invariance under bilateral rotations.

- Each of the two pairs is then acted on by a unilateral rotation, which we can call , which has the effect of converting them from mainly Werner states to mainly states with a large component of while the components of the other three Bell states are equal.

- The two impure states are then acted on by a bilateral XOR, and afterwards the target pair is locally measured along the z axis. The unmeasured source pair is kept if the target pair's spins come out parallel as in the case of both inputs being true states; and it is discarded otherwise.

- If the source pair has not been discarded it is converted back to a predominantly state by a unilateral rotation, and made rotationally symmetric by a random bilateral rotation.

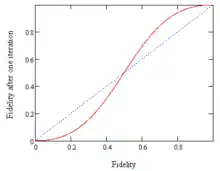

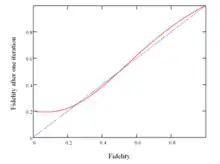

Repeating the outlined protocol above will distill Werner states whose purity may be chosen to be arbitrarily high from a collection M of input mixed states of purity but with a yield tending to zero in the limit . By performing another bilateral XOR operation, this time on a variable number of source pairs, as opposed to 1, into each target pair prior to measuring it, the yield can be made to approach a positive limit as . This method can then be combined with others to obtain an even higher yield.

Procrustean method

The Procrustean method of entanglement concentration can be used for as little as one partly entangled pair, being more efficient than the Schmidt projection method for entangling less than 5 pairs,[2] and requires Alice and Bob to know the bias () of the n pairs in advance. The method derives its name from Procrustes because it produces a perfectly entangled state by chopping off the extra probability associated with the larger term in the partial entanglement of the pure states:

Assuming a collection of particles for which is known as being either less than or greater than the Procrustean method may be carried out by keeping all particles which, when passed through a polarization-dependent absorber, or a polarization-dependent-reflector, which absorb or reflect a fraction of the more likely outcome, are not absorbed or deflected. Therefore, if Alice possesses particles for which , she can separate out particles which are more likely to be measured in the up/down basis, and left with particles in maximally mixed state of spin up and spin down. This treatment corresponds to a POVM (positive-operator-valued measurement). To obtain a perfectly entangled state of two particles, Alice informs Bob of the result of her generalized measurement while Bob doesn't measure his particle at all but instead discards his if Alice discards hers.

Stabilizer protocol

The purpose of an entanglement distillation protocol is to distill pure ebits from noisy ebits where . The yield of such a protocol is . Two parties can then use the noiseless ebits for quantum communication protocols.

The two parties establish a set of shared noisy ebits in the following way. The sender Alice first prepares Bell states locally. She sends the second qubit of each pair over a noisy quantum channel to a receiver Bob. Let be the state rearranged so that all of Alice's qubits are on the left and all of Bob's qubits are on the right. The noisy quantum channel applies a Pauli error in the error set to the set of qubits sent over the channel. The sender and receiver then share a set of noisy ebits of the form where the identity acts on Alice's qubits and is some Pauli operator in acting on Bob's qubits.

A one-way stabilizer entanglement distillation protocol uses a stabilizer code for the distillation procedure. Suppose the stabilizer for an quantum error-correcting code has generators . The distillation procedure begins with Alice measuring the generators in . Let be the set of the projectors that project onto the orthogonal subspaces corresponding to the generators in . The measurement projects randomly onto one of the subspaces. Each commutes with the noisy operator on Bob's side so that

The following important Bell-state matrix identity holds for an arbitrary matrix :

Then the above expression is equal to the following:

Therefore, each of Alice's projectors projects Bob's qubits onto a subspace corresponding to Alice's projected subspace . Alice restores her qubits to the simultaneous +1-eigenspace of the generators in . She sends her measurement results to Bob. Bob measures the generators in . Bob combines his measurements with Alice's to determine a syndrome for the error. He performs a recovery operation on his qubits to reverse the error. He restores his qubits . Alice and Bob both perform the decoding unitary corresponding to stabilizer to convert their logical ebits to physical ebits.

Entanglement-assisted stabilizer code

Luo and Devetak provided a straightforward extension of the above protocol (Luo and Devetak 2007). Their method converts an entanglement-assisted stabilizer code into an entanglement-assisted entanglement distillation protocol.

Luo and Devetak form an entanglement distillation protocol that has entanglement assistance from a few noiseless ebits. The crucial assumption for an entanglement-assisted entanglement distillation protocol is that Alice and Bob possess noiseless ebits in addition to their noisy ebits. The total state of the noisy and noiseless ebits is

where is the identity matrix acting on Alice's qubits and the noisy Pauli operator affects Bob's first qubits only. Thus the last ebits are noiseless, and Alice and Bob have to correct for errors on the first ebits only.

The protocol proceeds exactly as outlined in the previous section. The only difference is that Alice and Bob measure the generators in an entanglement-assisted stabilizer code. Each generator spans over qubits where the last qubits are noiseless.

We comment on the yield of this entanglement-assisted entanglement distillation protocol. An entanglement-assisted code has generators that each have Pauli entries. These parameters imply that the entanglement distillation protocol produces ebits. But the protocol consumes initial noiseless ebits as a catalyst for distillation. Therefore, the yield of this protocol is .

Entanglement dilution

The reverse process of entanglement distillation is entanglement dilution, where large copies of the Bell state are converted into less entangled states using LOCC with high fidelity. The aim of the entanglement dilution process, then, is to saturate the inverse ratio of n to m, defined as the distillable entanglement.

Applications

Besides its important application in quantum communication, entanglement purification also plays a crucial role in error correction for quantum computation, because it can significantly increase the quality of logic operations between different qubits. The role of entanglement distillation is discussed briefly for the following applications.

Quantum error correction

Entanglement distillation protocols for mixed states can be used as a type of error-correction for quantum communications channels between two parties Alice and Bob, enabling Alice to reliably send mD(p) qubits of information to Bob, where D(p) is the distillable entanglement of p, the state that results when one half of a Bell pair is sent through the noisy channel connecting Alice and Bob.

In some cases, entanglement distillation may work when conventional quantum error-correction techniques fail. Entanglement distillation protocols are known which can produce a non-zero rate of transmission D(p) for channels which do not allow the transmission of quantum information due to the property that entanglement distillation protocols allow classical communication between parties as opposed to conventional error-correction which prohibits it.

Quantum cryptography

The concept of correlated measurement outcomes and entanglement is central to quantum key exchange, and therefore the ability to successfully perform entanglement distillation to obtain maximally entangled states is essential for quantum cryptography.

If an entangled pair of particles is shared between two parties, anyone intercepting either particle will alter the overall system, allowing their presence (and the amount of information they have gained) to be determined so long as the particles are in a maximally entangled state. Also, in order to share a secret key string, Alice and Bob must perform the techniques of privacy amplification and information reconciliation to distill a shared secret key string. Information reconciliation is error-correction over a public channel which reconciles errors between the correlated random classical bit strings shared by Alice and Bob while limiting the knowledge that a possible eavesdropper Eve can have about the shared keys. After information reconciliation is used to reconcile possible errors between the shared keys that Alice and Bob possess and limit the possible information Eve could have gained, the technique of privacy amplification is used to distill a smaller subset of bits maximizing Eve's uncertainty about the key.

Quantum teleportation

In quantum teleportation, a sender wishes to transmit an arbitrary quantum state of a particle to a possibly distant receiver. Quantum teleportation is able to achieve faithful transmission of quantum information by substituting classical communication and prior entanglement for a direct quantum channel. Using teleportation, an arbitrary unknown qubit can be faithfully transmitted via a pair of maximally-entangled qubits shared between sender and receiver, and a 2-bit classical message from the sender to the receiver. Quantum teleportation requires a noiseless quantum channel for sharing perfectly entangled particles, and therefore entanglement distillation satisfies this requirement by providing the noiseless quantum channel and maximally entangled qubits.

See also

- Quantum channel

- Quantum cryptography

- Quantum entanglement

- Quantum state

- Quantum teleportation

- LOCC

- Purification theorem

Notes and references

- Bennett, Charles H.; DiVincenzo, David P.; Smolin, John A.; Wooters, William K. (1996). "Mixed State Entanglement and Quantum Error Correction". Phys. Rev. A. 54 (5): 3824–3851. arXiv:quant-ph/9604024. Bibcode:1996PhRvA..54.3824B. doi:10.1103/physreva.54.3824. PMID 9913930. S2CID 3059636.

- Bennett, Charles H.; Bernstein, Herbert J.; Popescu, Sandu; Schumacher, Benjamin (1996). "Concentrating Partial Entanglement by Local Operations". Phys. Rev. A. 53 (4): 2046–2052. arXiv:quant-ph/9511030. Bibcode:1996PhRvA..53.2046B. doi:10.1103/physreva.53.2046. PMID 9913106. S2CID 8032709.

- Bennett, Charles H.; Brassard, Gilles; Popescu, Sandu; Schumacher, Benjamin; Smolin, John A.; Wooters, William K. (1996). "Purification of Noisy Entanglement and Faithful Teleportation via Noisy Channels". Phys. Rev. Lett. 76 (5): 722–725. arXiv:quant-ph/9511027. Bibcode:1996PhRvL..76..722B. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.76.722. PMID 10061534. S2CID 8236531.

- Kwiat, Paul G.; Barraza-Lopez, Salvador; Stefanov, André; Gisin, Nicolas (2001), "Experimental entanglement distillation and 'hidden' non-locality", Nature, 409 (6823): 1014–1017, Bibcode:2001Natur.409.1014K, doi:10.1038/35059017, PMID 11234004, S2CID 4430054

- Yamamoto, Takashi; Koashi, Masato; Özdemir, Şahin Kaya; Imoto, Nobuyuki (2003), "Experimental extraction of an entangled photon pair from two identically decohered pairs", Nature, 421 (6921): 343–346, Bibcode:2003Natur.421..343Y, doi:10.1038/nature01358, PMID 12540894, S2CID 20824150.

- Pan, Jian-Wei; Gasparoni, Sara; Ursin, Rupert; Weihs, Gregor; Zeilinger, Anton (2003), "Experimental entanglement purification of arbitrary unknown states", Nature, 423 (6938): 417–422, Bibcode:2003Natur.423..417P, doi:10.1038/nature01623, PMID 12761543, S2CID 4393391.

- Pan, Jian-Wei; Simon, Christoph; Brunker, Časlav; Zeilinger, Anton (2001), "Entanglement purification for quantum communication", Nature, 410 (6832): 1067–1070, arXiv:quant-ph/0012026, Bibcode:2001Natur.410.1067P, doi:10.1038/35074041, PMID 11323664, S2CID 4424450.

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. (2000), Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521635039

- Bouwmeester, Dirk; Ekert, Artur; Zeilinger, Anton (2000), The Physics of Quantum Information: Quantum Cryptography, Quantum Teleportation, Quantum Computation, Springer, ISBN 3540667784

- Newton, I. (1687), Principia Mathematica, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press

- Luo, Zhicheng; Devetak, Igor (2007), "Efficiently implementable codes for quantum key expansion", Physical Review A, 75 (1): 010303, arXiv:quant-ph/0608029, Bibcode:2007PhRvA..75a0303L, doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.75.010303, S2CID 119491901

- Mark M. Wilde, "From Classical to Quantum Shannon Theory", arXiv:1106.1445.