Pope County, Arkansas

Pope County is a county in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 63,381.[2] The county seat is Russellville.[3] The county was formed on November 2, 1829, from a portion of Crawford County and named for John Pope, the third governor of the Arkansas Territory. Pope County was the nineteenth (of seventy-five) county formed. The county's borders changed eighteen times in the 19th century with the creation of new counties and adjustments between counties. The current boundaries were set on 8 March 1877.[4]

Pope County | |

|---|---|

Pope County Courthouse | |

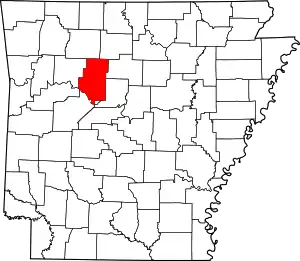

Location within the U.S. state of Arkansas | |

Arkansas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°25′35″N 93°01′55″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | November 2, 1829 |

| Named for | John Pope |

| Seat | Russellville |

| Largest city | Russellville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 831 sq mi (2,150 km2) |

| • Land | 813 sq mi (2,110 km2) |

| • Water | 18 sq mi (50 km2) 2.2% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 63,381 |

| • Estimate (2021) | 63,789 [1] |

| • Density | 76/sq mi (29/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 4th |

| Website | www |

Pope County is geographically diverse, with the Arkansas River Valley and its farmlands and towns in the southern portion and the Ozarks covering nearly two-thirds of the county to the north, including a portion of the rugged Boston Mountains, a deeply dissected plateau. Approximately 40% of the county is in the Ozark National Forest.

Pope County is an alcohol prohibition or dry county.

Pope County is part of the Russellville, Arkansas, Micropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Pope and Yell County.

History

Louisiana Purchase and Cherokee Lands

In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte sold French Louisiana to the United States, including all of Arkansas. Today, that transaction is known as the Louisiana Purchase.

By 1804, Present Jefferson, with others, looked to the new lands as a refuge for Indian peoples on lands near American settlements, keeping American settlers and Indian societies separate.[5]

Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, much of the region encompassing future Pope and other counties was designated as lands for the removal of eastern native tribes.[6] In about 1805, Cherokee living in southeast Missouri on the Mississippi River moved to the Arkansas River at the suggestion of Louisiana Territory Governor James Wilkinson. After the New Madrid earthquakes, most of the Cherokee—as many as 2,000 people—who had lived along the St. Francis River relocated to the Arkansas River Valley.[7]

In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in the Arkansas district of the Missouri Territory and tried to convince the Cherokee to move there voluntarily. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. The Cherokee who moved to this reservation became known as the "Old Settlers" or Western Cherokee.

A village on the Illinois Bayou served as the capitol of the Western Cherokees from 1813 to 1824.[8]

The Treaty of 1817 secured lands in Arkansas for the Western Cherokees north of the Arkansas River between Point Remove and Fort Smith and removed all citizens of the United States, except Persis Lovely, the widow of Indian Agenet William Lovely.[9] Most white settlers moved to new locations south of the river. By 1820, new Cherokee emigrants from the east had blended with the Old Settlers in a new "colony" with a string of Cherokee villages stretching for over 70 miles above Point Remove. About half of this distance was in the future Pope County.[10] An 1820 description by Territorial Governor James Miller called it a "lovely, rich part of the country".[11]

In 1818, the chief of the Arkansas Cherokees, Tol-on-tus-ky (Tolunskee or Tollontiskee), requested that the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions send a mission to Arkansas. The assignment was given to Cephas Washburn and his brother-in-law, Alfred Finney, who established a mission in 1820 on the west side of Illinois Bayou about four miles from the Arkansas River. The stream was navigable for keelboats about nine months of the year. The mission was named Dwight for the late Rev. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College and a corporate member of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.[12] The site was on a gentle rise covered with a growth of oak and pine at the foot of which issued a large spring of pure water. Above, below and opposite the site was plenty of excellent bottomland for cultivation. The mission was conveniently near Indian villages.[13] The mission eventually included more than 25 buildings, including seven log cabins, a dining hall, library, post office, lumber house, carpenter shop, saw mill, meat house, grist mill and barn.[14] The land where Dwight Mission buildings were is now under the waters of Lake Dardanelle, but the cemetery is still on the hill nearby.[15]

By the time Arkansas Territory was established in 1819, the western Cherokees represented at least 20 percent of the total population of the Territory, mostly centered along the Arkansas River and the future Pope County.

Arkansas Territory

Beginning in the 1820s, an increasing number of settlers came to Arkansas from southern states resulting in an environment for the eastern Indians who had moved to Arkansas that was similar to that from which they had been expelled.[16] Under a new treaty concluded on May 6, 1828, the western boundary of Arkansas was established with seven million acres to the west of that provided to the Cherokees "forever". The Cherokees agreed to leave the Arkansas lands within 14 months.[17] In 1829, all of the people at Dwight Mission moved to the new Indian Territory—in present-day Oklahoma—, where Dwight Mission was re-established in a new location.[18]

Pope County was established on November 2, 1829, ten years after the establishment of the Territory of Arkansas, with a temporary county seat to be at the home of John Bollinger.[19][20] A county seat selection commission elected in January 1830 chose the community of Scotia, home of Judge Andrew Scott, a neighbor of Bollinger, as the permanent county seat. With the formation of Johnson County in 1833, Scotia was but half a mile from the county line. The county seat was moved to Dwight and, then, in 1834, to Norristown, a growing town of the Arkansas River upstream and across the river from Dardanelle.[21]

Transportation into Arkansas' interior in the early years was mostly limited to river travel. While navigable, the Arkansas River was unpredictable, alternating between floods and droughts and infested with sandbars and snags. The winding Arkansas River passed through a vast swampy floodplain that covered much of eastern Arkansas, a breeding ground for malaria-bearing mosquitos. Settlers in those areas soon suffered from malarial fevers and other ailments and Arkansas gained a reputation as a sick and swampy land. Most pioneers avoided Arkansas and chose other destinations to settle in. Those who ventured further—into central and western parts of the territory, and Pope County—found good soils along the river valley and, in the mountains, healthy forests of pine, oaks, and hickory, with well-drained soils for farming in the valleys, a wealth of forage for grazing and an abundance of game animals. At the end of the territorial years, the bulk of the people of Pope County were plain-folk farmers, herders, and hunters.[22][23]

Antebellum Pope County

With the establishment of Yell County on December 5, 1840, the county seat was again on the periphery of the county and the county seat was moved to Dover—a more central location in the county—in 1841, after being selected by commissioners chosen for that purpose.[25] The first courthouse was a log structure.

With the outbreak of war with Mexico, in July 1846, a company of mounted infantry volunteers from Pope County, organized under Captain David West, along with volunteer units from other counties, entered service in the Indian Territory, replacing regular Army troops that had been dispatched to Mexico. The Arkansas volunteer troops provided an essential Federal military presence along the state's western border and eastern portion of the Indian Territory during a period of violent disputes between factions in the Cherokee Nation. After the arrival of three companies of regular Army dragoon recruits, the Pope County volunteers returned home in late April 1847.[26]

There were 695 white families in Pope County in 1850. The total population, according to the census, was 4,710; 10.2% were slaves (479 Individuals).[27] Only 1,640 individuals had been born in Arkansas. Most of the rest had been born in southern slave states. There were 11 who were foreign-born, including Dr. Thomas Russell. Sixty-two percent of the white population was under 15 years old. Twenty-three individuals were seventy or older; just two had made it to eighty. Over eighty percent of the population was supported by agriculture, mostly by self-sufficient farm families. Other occupations included carpentry, blacksmithing, tanning, lumbering, merchandising, and wagon-making. There were some lawyers, teachers, doctors, and preachers as well as millers, saddlers, shoemakers, cabinet-makers, county officials, and at least one tar kiln operator. There were only 100 slaveowners, and only ten owned ten or more slaves. Only three farmers had twenty or more slaves, enough to be considered "planters" in the slave culture of the south. There were no free blacks documented. There were thirteen sawmills—two steam-powered and the rest powered by water—, two tanneries, and a cotton factory producing 22,500 pounds of thread annually. Dr. Thomas Russell, for whom Russellville was named, owned 680 acres of land, four slaves, a store, and ten town lots. There were eleven one-teacher subscription schools with a total enrollment of 326 students. Churches totaled ten, according to the census, with 6 Methodist, 2 Baptist, 1 Cumberland Presbyterian, and 1 Old School Presbyterian. Principal causes of death, were, in order, croup, winter fever, cholera, hives, diarrhea, consumption and accidents. More than half of all deaths were infants under one year of age and only nine percent were over forty.[28]

Dover, the county seat, was the most important town between Little Rock and Fort Smith in 1850. Galla Rock, south of present-day Atkins, and Norristown were important trading centers with goods transported on the Arkansas River.[29]

In the late 1850s, Edward Payson Washburn took inspiration from Pope County scenes near the family's Norristown home for his most famous work, The Arkansas Traveler, the composition of which was derived from a story he heard from Colonel Sandford C. Faulkner. Supposedly occurring on the campaign trail in Arkansas in 1840, Colonel Faulkner's humorous story ends with a fiddle playing squatter being won over by the traveler (man on horse in image). Washburn's father was Cephas Washburn, founder of Dwight Mission.[30]

While the majority of the population of Pope County consisted of rural families, many were squatters on state or federal land. In 1851, about 76% of households did not own land and, in 1860, some 66% did not.[31]

In 1860, though its population had grown by 67.4% in a decade, Pope County was still sparsely settled. The slave population had grown to 12.4% (978 individuals).[27] Along with the rest of Arkansas, it was on an economic frontier attracting relatively large numbers of new settlers, mostly from other southern states.[32] Even though Arkansas had been a state since 1836, the few communities were small with limited development. The population in the 1860 census included 6,905 whites. There were 978 slaves, mostly in the agricultural areas in the southern part of the county. Most families were in the southern lowlands of the county. A railroad being developed to be built through the county—the Little Rock & Fort Smith—was to include a depot in Dover.[33]

Civil War

After South Carolina seceded in December 1860, an election was scheduled in Arkansas for February 1861 to vote on whether Arkansas would secede and if a secession convention would be called. In Pope County, prior to the election, secession was rejected four to one in a straw ballot.[34] In the statewide vote on February 18, secession was voted down.[35] The convention in March rejected an ordinance of secession, scheduled a vote of the people on secession for August, and adjourned subject to recall by the president of the convention.[36] After Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln issued a call for support from the states, many advocated for recalling the convention, but others were opposed, such as the delegate from Pope County, William Stout, who wrote, "I believe it is the President's duty to put down rebellion. I have always thought so."[37]

Convention President David Walker issued a proclamation calling for the convention to reconvene on May 6 where, in the final vote, the Arkansas Ordinance of Secession was passed by a vote of 69 to 1.[38]

In 1861, much of Pope County was still a wilderness frontier. There was no railroad. Roads were little more than tracks and there were no bridges crossing streams. The population was sparse with most dependent on subsistence farming. Many were squatters not owning the land their cabins were on.[39]

During the war, what little civil authority there was collapsed throughout Arkansas. By 1863, in most of the state, travel was dangerous, farming hazardous, and county government inoperative.[40] Pope County records at Dover were moved to a cave for protection. Several skirmishes took place in the county, but there were no major engagements. On April 8, 1865, Dover, including the courthouse was burned.[41][42][43]

The civil war's primary principles—for the South, independence and preservation of slavery, and for the North, restoration of the Union—soon lost their relevance in thinly settled Pope County. As in much of the region, the already hard lives of much of the population were disrupted by wartime loyalties separating unionists from rebels. For many, the struggle turned into a no-holds-barred conflict of killing and driving out opponents in the interest of ensuring the survival of families and allies.[44][45] Of those who were able to, many fled to safer places.[46][47] Most able-bodied men were away from home on one side or the other. Many of those left behind—women, old men, and children—fell prey to bands of guerrillas aligned to the Confederacy—called bushwhackers by Union sympathizers—or the Union—called jayhawkers by southerners. Some belonged to neither side, attacking both sides and committing murder and arson and "pilfering and robbing of clothes, rustling cattle, emptying corn bins, taking whatever they wanted".[48] Others actively supported one side or the other, such as William Stout's cooperation with the federals,[49] though it probably led to his assassination in 1865.

With Federal troops stationed at Lewisburg—on the river south of present-day Morrilton—and Clarksville in 1864, foraging parties seeking supplies ranged into Pope County. Many families remaining in the county suffered incursions by the military and guerilla bands.[50]

Following the civil war, Pope County remained sparsely settled, with a census population in 1870 of only 503 more people than had been recorded before the war. Many of the people who had fled the upheaval and uncertainties of the war years never returned and, of course, many former residents had not survived the conflict. The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad had been postponed by the conflict with the first rails not laid until 1869.[51]

Reconstruction

Arkansas became the second former Confederate state to be fully restored to the Union in June 1868, but political and social stability was still years away. During the military reconstruction period (1867-1868), when Arkansas was placed in the Fourth Military District, companies E and G of the Nineteenth Infantry,[52] were stationed in Pope County and headquartered at Dover for a year and a half.[53] In 1868, a militia law passed by the general assembly authorized the governor to enroll a state guard modeled, generally, after the U. S. Army.[54] Elements of this guard would be used four years later in Pope County.

Between 1865 and 1870, at least five county officials were assassinated:[55] Sheriff Archibald D. Napier and Deputy Sheriff Albert Parks on October 24, 1865, County Clerk William Stout on December 4, 1865, Sheriff W. Morris Williams on August 20, 1866, and Russellville Postmaster John L. Harkey on July 27, 1868. Napier and Williams both served as Captain of the Third Arkansas Cavalry Regiment (Union), Company I where Wallace H. Hickox, Stout's successor, was a lieutenant and John H. Williams, a successor to Parks and Morris Williams' brother, was a bugler.[56]

On March 1, 1870, the new Pope County jail in Dover was burned.[57] A man named Glover later claimed responsibility.[58]

Militia War

A period of a little over seven months in 1872 and 1873 came to be known as the Pope County Militia War. However, there were no battles or skirmishes. There were no engagements between organized opponents of any kind. Instead, an unofficial militia,[59] headed by four county officers, exerted excessive and harsh control over the county, including threats to burn Dover, the county seat.[60][61] By the end of the period, three of the four officials were dead.

Late Nineteenth Century

By June 1873, regular service on the Little Rock & Fort Smith Railroad extended all the way through the county as far as Clarksville in Johnson County. County commerce that had previously made Dover the business center of the county moved to Russellville or Atkins.

County Seat move from Dover to Russellville

With the new railroad running eight miles south of the county seat at Dover and the gradual relocation of county commerce toward Russellville and Atkins, moving the county seat was inevitable. Russellville was developing into the business center of the county[62] and a newer town, Atkins, was growing fast and would compete as a potential new location for the county seat.

It took 15 years from an act from the Arkansas General Assembly moving the county seat to Russellville—reversed the next year, sending it back to Dover—until the new courthouse was completed in Russellville. Dover had been selected in the 1840s for its more central location in the county. Thirty years later, the southern townships held the majority of the population and paid a large majority of the taxes.[63]

County Seat—1870s

An act to move the county seat passed in the General Assembly in 1873[64] but was repealed during a special session of the General Assembly in 1874.[65] The moving of the county seat from Russellville back to Dover in 1874 was because moving the county seat from Dover to Russellville had not been done by the citizens but rather by the legislature. The railroad had just opened up through Russellville and the citizens did not see that the business center of the county had so shifted yet as to justify the change.[66]

Winds from a storm on March 8, 1878, damaged the county courthouse in Dover, rendering it "unfit and unsafe".[67] With the county having no funds to repair the structure, its condition became a consideration for some in the issue of moving the county seat, with citizens of Russellville offering a building site and $2,500 to build a new courthouse there at no cost to the taxpayers.[68][69] A church was used for a courtroom during terms of the circuit court while the courthouse was unavailable.[70]

On September 2, 1878, an election was held, as ordered by the county court[71] to determine:

- whether to move the county seat from Dover, and

- whether to change the county seat to Atkins or to Russellville if the voters decided to move the seat from Dover.

Following the special election, the county clerk certified that a majority (1,240) of the qualified electors voted to move the county seat from Dover. However, neither Atkins nor Russellville received enough votes to determine where the new county seat would be located. The results of the election were challenged in court.[72]

On April 30, 1879, an election was ordered[73] by the county court to be held June 20, 1879, to determine whether the county seat would be changed to Russellville or to Atkins. On the 17th of June, Russellville citizens increased the amount of their bond for building a new courthouse from $2,500 to $10,000.[74]

The results of that election were moot after courts overturned the results of the September 1878 vote. The case made it to the Arkansas Supreme Court which returned the case to the circuit court of Judge W. D. Jacoway.[75] Jacoway's subsequent ruling was that there were 200 votes of men voting in the wrong township and 150 ballots that were marked "for Russellville" that were not marked for a move "from" Dover. The ruling said that the proposition to move the county seat received just 890 votes. There were 2,266 qualified voters at the time of the election. The law required a majority of qualified voters to approve the move of the county seat,[76] which, for this election, would have been 1,134 votes "for" the move.[77]

During the 1879 September term of Pope County Circuit Court, a grand jury condemned the courthouse as "wholy unfit for use as a Court House."[78]

County Seat—1880s

With the 1878 vote to move the county seat from Dover reversed, repairs to the county courthouse in Dover were made in the early 1880s.[79][80] The contract for the repairs was to W. R. Cox of Atkins for $1,000.[81]

A September 6, 1886, election—ordered on July 21, 1886, in response to two petitions[82]—had three proposals:

- Shall the County Seat be removed or changed? (removed meant moved)

- Shall the County Seat be removed from Dover to Russellville?

- Shall the County Seat be removed from Dover to Atkins?

Again, a majority voted to move the county seat from Dover, but neither Russellville nor Atkins received enough votes to move the County Seat to either place.[76] Pope County had 3,688 registered voters at the time. The move to Russellville received 1,485 votes (40.2% of registered voters) and Atkins garnered 1200 (32.5% of the registered voters).[83]

In October 1886, the county court set aside the election, deciding that the election was void for bribery, Russellville having offered to erect a courthouse if she was selected as the county seat. The decision was appealed to the circuit court, where M. L. Davis was elected special judge to try the contested case. On November 12, Davis reversed the county court's decision and ordered that an election be held on March 19, 1887, to determine whether the county seat would be moved to Russellville or to Atkins.[83] His decision was appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

The offer that Russellville's leading citizens made included lots in Russellville as the site for a new courthouse and a $50,000 bond for the construction, without cost to the county, of a "good and sufficient two story brick court house" and a "good, sufficient, and commodious jail". Before the September 1886 election, citizens in Atkins made a very similar offer.[84]

The certified result of the March 19, 1887, special election was 1,399 votes for Russellville and 1271 for Atkins, with Russellville selected by a margin of 128 votes out of 2,670 total votes cast.[85]

The Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed the ruling by Judge Davis on June 4, 1887,[86] clearing the way for the county seat to be moved to Russellville and for the construction of a new courthouse and jail.[87] Title to properties in Russellville for the new courthouse and jail had been tendered to the county in March.[88] On June 13, the bondsmen for the new courthouse held a meeting and took steps deemed necessary to start the work[89] and on September 23, the cornerstone was laid.[90] County records were moved to Russellville in August and, temporarily, the county courtroom and clerk's office were upstairs in the R. J. Wilson Building.[91]

The new courthouse and jail in Russellville were accepted as completed on May 16, 1888, by J.M. Haney, W. H. Poynter, and L. D. Ford, commissioners appointed by the county court to examine and receive the new county structures.[92]

Railroads, ferry, and a bridge

With the completion of the railroad through the county and the move of the county seat, some smaller communities such as Norristown [93] and Dover went into a period of decline or disappeared.

On August 15, 1893, train operations began on the Dardanelle and Russellville Railroad (D&R). A 4.8-mile (7.7 km) shortline that still exists, the D&R railroad runs from Russellville to the north bank of the Arkansas River at North Dardanelle, across from Dardanelle, Arkansas. The line was originally built primarily to transport agricultural products—primarily cotton—from Dardanelle to the LR&FS depot in Russellville. For the first eight years of operation, freight and passengers crossed the river on a ferry.

In 1891, the ferry across the river at Dardanelle was supplanted by the Dardanelle pontoon bridge which was in use for nearly four decades except for periods when its operation was interrupted because of high river flows or other disruptions.

Twentieth Century

On the night of January 16, 1906, nearly half of the business district of Russellville was destroyed by fire. The county courthouse was spared, though most of the buildings in its block of the city were lost.[94]

In 1931, the 1878 county courthouse was demolished and replaced with the current building.[95][96]

Arkansas's first highway rest area was built in Pope County on Highway 7 in the 1930s. Despite its challenging terrain, Highway 7 became a major route for travelers, connecting Russellville and Harrison. This was back when cars were a relatively new invention and there were few places to stop and take a break. "Rotary Ann" rest stop was named after the Rotary Club's ladies' auxiliary. The Russellville branch recognized the need for a rest area with bathrooms and scenic views along Highway 7 and worked with the Rotary Club to create a scenic overlook in the 1930s.[97][98]

In 1954, the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers dug a new, straight channel for the Arkansas River across the 6-mile "bend" of Pope County's Holla Bend.[99] The project was part of the long-term development of the river for flood control and mitigation and future use of the river for navigation. The new channel is entirely in Pope County. Holla Bend, now on the south side of the river, is accessible by land only through neighboring Yell County. After the channel project was completed, the Corps turned 4,068 acres back to the General Services Administration (GSA), advising the GSA that the land, which had been part of the "Holla Bend Cutoff" flood control project, was surplus. Following a period of uncertainty due to local opposition, Holla Bend was acquired by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in 1957 for development and use as a national wildlife refuge.[100][101] Additional acquisitions have brought the total number of acres to 7,055 currently under refuge management.[102]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 831 square miles (2,150 km2), of which 813 square miles (2,110 km2) is land and 18 square miles (47 km2) (2.2%) is water.[103]

Major highways

.svg.png.webp) Interstate 40

Interstate 40 U.S. Highway 64

U.S. Highway 64 Arkansas Highway 7

Arkansas Highway 7 Arkansas Highway 7S

Arkansas Highway 7S Arkansas Highway 7T

Arkansas Highway 7T Arkansas Highway 16

Arkansas Highway 16 Arkansas Highway 27

Arkansas Highway 27 Arkansas Highway 105

Arkansas Highway 105 Arkansas Highway 123

Arkansas Highway 123 Arkansas Highway 124

Arkansas Highway 124 Arkansas Highway 164

Arkansas Highway 164 Arkansas Highway 247

Arkansas Highway 247 Arkansas Highway 324

Arkansas Highway 324 Arkansas Highway 326

Arkansas Highway 326 Arkansas Highway 331

Arkansas Highway 331 Arkansas Highway 333

Arkansas Highway 333 Arkansas Highway 363

Arkansas Highway 363.svg.png.webp) Arkansas Highway 980

Arkansas Highway 980

Adjacent counties

- Newton County (northwest)

- Searcy County (northeast)

- Van Buren County (northeast)

- Conway County (southeast)

- Yell County (south)

- Logan County (southwest)

- Johnson County (west)

National protected areas

- Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge (part)

- Ozark National Forest (part)

- East Fork Wilderness[104]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 1,483 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,850 | 92.2% | |

| 1850 | 4,710 | 65.3% | |

| 1860 | 7,883 | 67.4% | |

| 1870 | 8,386 | 6.4% | |

| 1880 | 14,322 | 70.8% | |

| 1890 | 19,458 | 35.9% | |

| 1900 | 21,715 | 11.6% | |

| 1910 | 24,527 | 12.9% | |

| 1920 | 27,153 | 10.7% | |

| 1930 | 26,547 | −2.2% | |

| 1940 | 25,682 | −3.3% | |

| 1950 | 23,291 | −9.3% | |

| 1960 | 21,177 | −9.1% | |

| 1970 | 28,607 | 35.1% | |

| 1980 | 39,021 | 36.4% | |

| 1990 | 45,883 | 17.6% | |

| 2000 | 54,469 | 18.7% | |

| 2010 | 61,754 | 13.4% | |

| 2020 | 63,381 | 2.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[105] 1790–1960[106] 1900–1990[107] 1990–2000[108] 2010–2017[109] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 50,037 | 78.95% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 2,060 | 3.25% |

| Native American | 456 | 0.72% |

| Asian | 664 | 1.05% |

| Pacific Islander | 23 | 0.04% |

| Other/Mixed | 3,726 | 5.88% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6,415 | 10.12% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 63,381 people, 22,579 households, and 14,881 families residing in the county.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census,[112] there were 54,469 people, 20,701 households, and 15,008 families residing in the county. The population density was 67 inhabitants per square mile (26/km2). There were 22,851 housing units at an average density of 28 per square mile (11/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 93.73% White, 2.61% Black or African American, 0.68% Native American, 0.64% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.93% from other races, and 1.39% from two or more races. 2.06% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 20,701 households, out of which 34.30% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.60% were married couples living together, 10.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.50% were non-families. 23.00% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.55 and the average family size was 3.00.

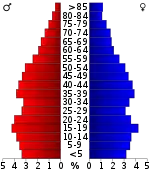

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.50% under the age of 18, 11.60% from 18 to 24, 28.20% from 25 to 44, 21.90% from 45 to 64, and 12.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.40 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.10 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $32,069, and the median income for a family was $39,055. Males had a median income of $29,914 versus $19,307 for females. The per capita income for the county was $15,918. About 11.60% of families and 15.20% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.80% of those under age 18 and 14.00% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Over the past few election cycles, Pope County has trended heavily towards the GOP. The last Democrat (as of 2020) to carry this county was Bill Clinton in 1996.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 18,081 | 74.01% | 5,772 | 23.62% | 579 | 2.37% |

| 2016 | 16,256 | 72.03% | 5,000 | 22.15% | 1,313 | 5.82% |

| 2012 | 14,763 | 72.23% | 5,126 | 25.08% | 550 | 2.69% |

| 2008 | 15,568 | 70.51% | 6,002 | 27.18% | 509 | 2.31% |

| 2004 | 13,614 | 65.13% | 7,100 | 33.97% | 188 | 0.90% |

| 2000 | 11,244 | 61.04% | 6,669 | 36.20% | 509 | 2.76% |

| 1996 | 8,243 | 43.75% | 8,433 | 44.76% | 2,164 | 11.49% |

| 1992 | 8,056 | 45.10% | 7,704 | 43.13% | 2,102 | 11.77% |

| 1988 | 10,084 | 66.68% | 4,941 | 32.67% | 98 | 0.65% |

| 1984 | 10,667 | 67.28% | 5,082 | 32.05% | 106 | 0.67% |

| 1980 | 7,217 | 50.72% | 6,364 | 44.72% | 649 | 4.56% |

| 1976 | 4,348 | 34.15% | 8,355 | 65.62% | 29 | 0.23% |

| 1972 | 6,917 | 67.52% | 3,302 | 32.23% | 25 | 0.24% |

| 1968 | 3,319 | 38.30% | 2,578 | 29.75% | 2,769 | 31.95% |

| 1964 | 2,651 | 34.07% | 4,972 | 63.91% | 157 | 2.02% |

| 1960 | 2,573 | 46.04% | 2,760 | 49.38% | 256 | 4.58% |

| 1956 | 2,267 | 44.94% | 2,753 | 54.57% | 25 | 0.50% |

| 1952 | 2,226 | 42.27% | 3,036 | 57.65% | 4 | 0.08% |

| 1948 | 764 | 20.56% | 2,525 | 67.95% | 427 | 11.49% |

| 1944 | 805 | 28.14% | 2,048 | 71.58% | 8 | 0.28% |

| 1940 | 770 | 16.88% | 3,765 | 82.55% | 26 | 0.57% |

| 1936 | 348 | 11.49% | 2,678 | 88.38% | 4 | 0.13% |

| 1932 | 280 | 10.36% | 2,391 | 88.49% | 31 | 1.15% |

| 1928 | 1,559 | 36.11% | 2,735 | 63.35% | 23 | 0.53% |

| 1924 | 479 | 21.23% | 1,581 | 70.08% | 196 | 8.69% |

| 1920 | 1,120 | 34.24% | 2,082 | 63.65% | 69 | 2.11% |

| 1916 | 783 | 26.71% | 2,148 | 73.29% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1912 | 334 | 13.14% | 1,517 | 59.70% | 690 | 27.15% |

| 1908 | 811 | 31.56% | 1,664 | 64.75% | 95 | 3.70% |

| 1904 | 850 | 36.64% | 1,424 | 61.38% | 46 | 1.98% |

| 1900 | 835 | 30.68% | 1,871 | 68.74% | 16 | 0.59% |

| 1896 | 762 | 24.60% | 2,315 | 74.75% | 20 | 0.65% |

Townships

Townships in Arkansas are the divisions of a county. Each township includes unincorporated areas; some may have incorporated cities or towns within part of their boundaries. Arkansas townships have limited purposes in modern times. However, the United States census does list Arkansas population based on townships (sometimes referred to as "county subdivisions" or "minor civil divisions"). Townships are also of value for historical purposes in terms of genealogical research. Each town or city is within one or more townships in an Arkansas county based on census maps and publications. The townships of Pope County are listed below; listed in parentheses are the cities, towns, and/or census-designated places that are fully or partially inside the township. [114][115]

Pope County formerly included 10 more townships. Allen Township was moved into Hogan Township around 1910, and Hill Township, Galla Creek Township, Independence Township, Lee Township, North Fork Township, Sand Spring Township, and Sulphur Township were also formerly active townships in Pope County. Holla Bend Township, containing the Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge, has also been disbanded.

| Township | FIPS code | ANSI code (GNIS ID) |

Population center(s) |

Pop. (2010) |

Pop. density (/mi2) |

Pop. density (/km2) |

Land area (mi2) |

Land area (km2) |

Water area (mi2) |

Water area (km2) |

Geographic coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayliss | 05-90159 | 69697 | 708 | 24.6 | 9.5 | 28.81 | 74.62 | 0.0979 | 0.2536 | 35°24′10″N 93°14′06″W | |

| Burnett | 05-90558 | 69698 | 452 | 20.9 | 8.1 | 21.65 | 56.07 | 0.1051 | 0.2722 | 35°19′10″N 92°52′33″W | |

| Center | 05-90735 | 69699 | 515 | 36.8 | 14.2 | 13.99 | 36.23 | 0.0339 | 0.0878 | 35°24′20″N 92°57′16″W | |

| Clark | 05-90813 | 69700 | London | 2969 | 115.3 | 44.6 | 25.73 | 66.64 | 6.0444 | 15.6549 | 35°19′45″N 93°14′46″W |

| Convenience | 05-90921 | 69701 | 933 | 50.4 | 19.4 | 18.53 | 47.99 | 0.0942 | 0.2440 | 35°20′00″N 92°56′41″W | |

| Dover | 05-91134 | 69702 | Dover | 5277 | 119.1 | 46.0 | 44.29 | 114.7 | 0.3637 | 0.9420 | 35°23′30″N 93°07′01″W |

| Freeman | 05-91377 | 69703 | 98 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 119.78 | 310.2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 35°39′10″N 93°04′06″W | |

| Galla | 05-91407 | 69704 | Pottsville | 3523 | 88.7 | 34.3 | 39.71 | 102.8 | 1.8410 | 4.7682 | 35°13′15″N 93°02′46″W |

| Griffin | 05-91536 | 69705 | 901 | 26.5 | 10.2 | 33.96 | 87.96 | 0.1106 | 0.2865 | 35°25′30″N 92°52′36″W | |

| Gum Log | 05-91560 | 69706 | 1420 | 71.6 | 27.6 | 19.84 | 51.39 | 0.0142 | 0.0368 | 35°16′30″N 92°59′51″W | |

| Illinois | 05-91812 | 69707 | Russellville | 25841 | 540.9 | 208.9 | 47.77 | 123.7 | 6.6022 | 17.0996 | 35°17′00″N 93°07′46″W |

| Jackson | 05-91875 | 69708 | Hector | 1191 | 11.5 | 4.4 | 103.72 | 268.6 | 0.0505 | 0.1308 | 35°29′20″N 92°57′01″W |

| Liberty | 05-92181 | 69709 | 805 | 14.2 | 5.5 | 56.64 | 146.7 | 0.0028 | 0.0073 | 35°29′40″N 93°03′16″W | |

| Martin | 05-92415 | 69710 | 1482 | 23.7 | 9.2 | 62.46 | 161.8 | 0.3931 | 1.0181 | 35°28′25″N 93°10′06″W | |

| Moreland | 05-92553 | 69711 | 700 | 52.2 | 20.2 | 13.40 | 34.71 | 0.0683 | 0.1769 | 35°21′30″N 92°59′46″W | |

| Phoenix | 05-92871 | 69712 | 334 | 26.7 | 10.3 | 12.51 | 32.40 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 35°24′30″N 93°00′31″W | |

| Smyrna | 05-93420 | 69713 | 173 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 70.69 | 183.1 | 0.0218 | 0.0565 | 35°38′10″N 92°53′46″W | |

| Valley | 05-93765 | 69714 | 2776 | 125.7 | 48.5 | 22.09 | 57.21 | 0.0144 | 0.0373 | 35°20′05″N 93°02′46″W | |

| Wilson | 05-94089 | 69715 | Atkins | 4371 | 77.6 | 30.0 | 56.32 | 145.9 | 3.0305 | 7.8490 | 35°13′30″N 92°55′01″W |

| Source: "Census 2000 U.S. Gazetteer Files". U.S. Census Bureau, Geography Division. | |||||||||||

See also

Notes

- https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/popecountyarkansas/PST045221

- "QuickFacts Pope County, Arkansas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Atlas of Historical County Boundaries - Arkansas". The Newberry Library. The Newberry. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- Everrett, Derek R. (Spring 2008). "On the Extreme Frontier: Crafting the Western Arkansas Boundary". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 67 (1): 3–4. JSTOR 40038311. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

Although mandatory relocation would not be established until 1830, by 1804 President Jefferson and others already looked to the western lands as a refuge for Indian peoples occupying land nearer to American settlements, particularly in the southern states and territories. Keeping American settlers and Indian societies separate in order to keep the peace seemed sensible, and the vast tracts beyond the great river offered Jefferson his solution.

- Bolton, S. Charles (Autumn 2003). "Jeffersonian Indian Removal and the Emergence of Arkansas Territory". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Association. 62 (3): 253–271. doi:10.2307/40024265. JSTOR 40024265. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

... for twenty years, beginning in 1808, Arkansas was the government's destination of choice for removed tribes.

- Myers, Robert A. (Summer 1997). "Cherokee Pioneers in Arkansas: The St. Francis Years, 1785-1813". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayettevill, Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Association. 56 (2): 153–156. doi:10.2307/40023675. JSTOR 40023675. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

By the time the New Madrid earthquakes drowned out the Cherokee settlements on the St. Francis River, their population there had increased to two thousand persons. The principal Cherokee town was undoubtedly the largest settlement in Arkansas at the time, with a population roughly four times greater than Arkansas Post.

- "Takatoka (1755?–1824)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- "Treaty with the Cherokee, 1817". Tribal Treaties Database. Oklahoma State University Libraries. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

Art. 5 - The United States bind themselves in exchange for the lands ceded in the first and second articles hereof, to give to that part of the Cherokee nation on the Arkansas as much land on said river and White river as they have or may hereafter receive from the Cherokee nation east of the Mississippi, acre for acre, as the just proportion due that part of the nation on the Arkansas agreeably to their numbers; which is to commence on the north side of the Arkansas river at the mouth of Point Remove or Budwell's Old Place; thence, by a straight line, northwardly, to strike Chataunga mountain, or the hill first above Shield's Ferry on White river, running up and between said rivers for complement, the banks of which rivers to be the lines; and to have the above line, from the point of beginning to the point on White river, run and marked, which shall be done soon after the ratification of this treaty; and all citizens of the United States, except. P. Lovely, who is to remain where she lives during life, removed from within the bounds as above named. And it is further stipulated, that the treaties heretofore between the Cherokee nation and the United States are to continue in full force with both parts of the nation, and both parts thereof entitled to all the immunities and privilege which the old nation enjoyed under the aforesaid treaties; the United States reserving the right of establishing factories, a military post, and roads within the boundaries above defined.

- Markman, Robert Paul (1972). "IV". The Arkansas Cherokees: 1817-1828 (PhD). The University of Oklahoma. p. 107.

- Morse, Jedediah (1822). A Report to the Secretary of War of the United States, on Indian Affairs. pp. 212–213. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

The settlement of the Cherokees is scattered for a long extent on the river, and appears not much different from those of the white people. They are considerably advanced towards civilization and were very decent in their deportment. They inhabit a lovely, rich part of the country.

- Jones, Dorsey D. (1944). "Cephas Washburn and His Work in Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 3 (2): 125–136. doi:10.2307/40018753. JSTOR 40018753. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- Morse, Jedediah (1822). A Report to the Secretary of War of the United States, on Indian Affairs. pp. 214–217. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

The site selected for the Establishment, is on the west bank of the Illinois river, a northern branch of the Arkansaw, about five miles from their junction, on a gentle eminence, covered with a growth of oak and pine. At the foot of the eminence issues a large spring of pure water, yielding an abundant supply of this comfort and necessary of life. The Illinois, three fourths of the year, is navigable for keel boats, as far as the Establishment. Above, opposite, and below it, is plenty of excellent bottom land for culture, and conveniently near a good mill seat. From the circumstances mentioned, the situation promises to be very eligible; pleasant and healthful; and is also conveniently near the Indian villages. It is one hundred miles below Fort Smith; two hundred above the Arkansaw post; and about five hundred, as the river runs, from the mouth of the Arkansaw. The first log-house was raised here the 28th September, 1820.

- Logan, Charles Russel (1997). The Promised Land: The Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal, 1794-1839. Little Rock, Arkansas: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. p. 16.

- Davis, Hester A (October 1999). "The Cherokee in Arkansas". Central States Archeological Journal. Central States Archaeological Societies, Inc. 46 (4): 191. JSTOR 43144201. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- Bolton, S. Charles (Autumn 2003). "Jeffersonian Indian Removal and the Emergence of Arkansas Territory". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Association. 62 (3): 258–259. doi:10.2307/40024265. JSTOR 40024265. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- Littlefield, Danel F.; Underhill, Lonnie E. (Summer 1972). "The Cherokee Agency Reserve, 1828-1886". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Association. 31 (2): 167–168. doi:10.2307/40022264. JSTOR 40022264. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

The Indians left behind them many well-cultivated farms and substantial dwellings. White settlers moved onto the land and occupied the improvements. Many even purchased the land and improvements from the departing Cherokees, who, of course, had no right to sell them.

- Davis, Hester A (October 1999). "The Cherokee in Arkansas". Central States Archeological Journal. Central States Archaeological Societies, Inc. 46 (4): 191. JSTOR 43144201. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

All the people at Dwight Mission moved 150 miles west into Indian Territory (Oklahoma) in 1829 and most of the Cherokee followed. The reservation was dissolved and the area of the Ozarks was opened for white settlement.

- "An act to erect and establish the County of Pope". Organic act of 2 November 1829. General Assembly of the Territory of Arkansas. p. 42.

Be it further enacted by the General Assembly of the Territory of Arkansas, That all the part of the county of Crawford, included within the following boundaries,... be, and the same is hereby, erected into a separate and distinct county, to be called and known by the name of Pope.

- Acts passed at The Sixth Session of the General Assembly of the Territory of Arkansas. Little Rock: William E Woodruff. 1830. p. 43. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

Be it further enacted that the temporary seat of justice of the said county of Pope, hereby erected and established, shall be at the present residence of John Bollinger; and that an election shall be held... on the first Monday in January next for the purpose of electing one commissioner from each of said townships..., to locate the seat of justice in and for the county of Pope..

(Note 1: The act actually took effect on December 25th, though John Pope approved it on November 2nd. Virtually all references give November 2nd for the day that Pope County was established.) (Note 2: John Bollinger was one of 13 county magistrates appointed 20 November 1829.) - Hempstead, Fay (1890). A Pictorial History of Arkansas. St. Louis and New York: N. D. Thompson Publishing Company. p. 946. ISBN 0-89308-074-8. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

... an election for Commissioners was directed by the Act to be held to locate the county seat permanently. The place selected for the purpose was Scotia, the residence place of Judge Andrew Scott, which was the next house to Bollinger's in the neighborhood settlement, and was made the county seat in 1830...

- Otto, John Solomon (Fall 1986). ""On a Slow Train Through Arkansaw" : Creating an Image for a Mountain State". Appalacian Journal. Boone, North Carolina: Appalachian Journal and Appalachian State University. 14 (1): 70. JSTOR 40932861. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- Blansett, Kent (Fall 2010). "Intertribalism in the Ozarks, 1800-1865". American Indian Quarterly. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 34 (4): 478–479. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.34.4.0475. JSTOR 10.5250/amerindiquar.34.4.0475. S2CID 161921853. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

Most of those pioneers who chose to stay came from Appalachian stock and settled individually throughout the area. Log cabins with dirt floors, a small garden for corn, and supplies for trapping and hunting were all they needed to scratch out a life in the hills.

- "Arkansas Traveler Print" (PDF). Arkansas Life. Little Rock: Arkansas Democrat Gazette: 76–77. July 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- Hempstead, Fay (1890). A Pictorial History of Arkansas. St. Louis and New York: N. D. Thompson Publishing Company. p. 946. ISBN 0-89308-074-8. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

It was located at Dover by Benjamin Lanford, Webster Jamison and James Burton. It remained there until March 19th, 1887...

- Trotter, Richard L. (Winter 2001). "For the Defense of the Western Border: Arkansas Volunteers on the Indian Frontier, 1846-1847". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Little Rock, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 60 (4): 394–410. doi:10.2307/40038254. JSTOR 40038254. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

With the majority of the Sixth Infantry and First Dragoons en route to Mexico, the volunteers were essential to maintaining a strong federal presence along the Arkansas border and preventing further violence among the Cherokees. The volunteers rounded up deserters, criminals, and murderers for prosecution by local authorities or military courts and helped prevent theft of livestock and property from local inhabitants. Though they never faced combat, the volunteers experienced many of the same hardships and privations as their brethren in Mexico. Disease plagued troops, and unfamiliarity with army regulations caused continual conflict between volunteer and regular army commanders.

- Duncan, Georgena (Winter 2007). "Manumission in the Arkansas River Valley: Three Case Histories". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 66 (4): 422–443. JSTOR 40031122. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- Worley, Ted R. (Summer 1954). "Pope County One Hundred Years Ago". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Van Buren - Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 13 (2): 196–204. doi:10.2307/40027520. JSTOR 40027520. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Field Operations of the Division of Soils, Volume 15. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agricuture, Bureau of Soils. 1913. p. 1222. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

However, with the building of the railroad... in 1873 Russellville and Atkins became the most important towns in the county.

- Anderson, Mabel W. (July 1907). Sturm, G. P. (ed.). "The Southern Artist". Sturm's Oklahoma Magazine. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Sturm Publishing Company. IV (5 and 6): 5–7.

(One day)...Edward remarked that he believed he would paint a picture and call it "The Arkansas Travelor." A few days later... he began to paint...One day he and his brother visited their old home at Dwight to look at the memorable spring that once slaked the thirst... and in passing one of the old mission houses they saw a young girl holding a looking class in one hand while with the other she combed and brushed a lovely suit of hair... immediately upon reaching home he sketched the character of the girl holding the glass and combing her hair.

- Boyette, Gene W. (1990). Hardscrabble Frontier : Pope County, Arkansas in the 1850s. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, Inc. p. 8. ISBN 978-0819177087.

- Moneyhon, Carl H. (1999). "The Slave Family in Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 58 (1): 27. doi:10.2307/40026272. JSTOR 40026272.

- "Pope County". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "4) Arkansas and The Union, November, 1860 - March, 1861". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780817305222.

In Pope County secession was voted down four to one in a straw ballot, and thirty-three guns fired to honor the occasion.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "4) Arkansas and The Union, November, 1860 - March, 1861". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780817305222.

On February 18, 1861, the voters... (in) near freezing weather voted down secession... 23,626 for the Union and 17,927 for secession... The summoning of a convention was approved 27,412 to 15, 826.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "5) Arkansas Leaves the Union". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 48 to 56. ISBN 9780817305222.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "5) Arkansas Leaves the Union". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9780817305222.

I believe it is the President's duty to put down rebellion. I have always thought so. I have always thought that General Jackson was right in 33 if he was right then Lincoln is right now but it Seems that there is going to be war between the north & the South—for me to take the Side of the north against my brethren of the South that would brand me forever with valainy [sic] that would be too bad and roll up my Sleeves and go to kiling off men that never did me any harm and never intends to do me any...The Secessionists here are rejoicing best pleased in the world a thousand times better pleased when they heard that Fort Sumpter was taken than they would have been to have heard that a plan was devised to put at rest forever all political differences and raised the Strips and Stars again over a free contented happy and prosperous people—these are hard things to say but I believe in my soul it is so and can I ever cooperate with a people whose heart is so decidedly in the wrong place I think no I see no way to do that—

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "5) Arkansas Leaves the Union". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780817305222.

- Shea, William L (Summer 2011). "The War We Have Lost". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 70 (2): 101. JSTOR 23046159. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "7) The Third Year of the War". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780817305222.

- Gillet, Orville; Worley, Ted R. (Summer 1958). "Diary of Orville Gillet, U. S. A., 1864-1865". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Little Rock and Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 17 (2): 193. doi:10.2307/40038015. JSTOR 40038015. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

April 8. Staid in Camp all day. Rebs burnt 23 Buildings in Dover

- "Dover (Pope County)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- "Arkansas's Iliad". The New York Herald. No. 13189. James Gordon Bennett Jr. September 30, 1872. p. 7. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

We lost nearly all our town in the war. Our own boys burned it to keep the federals from occupying it, after they had driven out the women and children.

- "Arkansas's Iliad". The New York Herald. No. 13189. James Gordon Bennett Jr. September 30, 1872. p. 7. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

It was neutral ground, and successively over-ran by federals from Dardanelle and Lewisburg, and by rangers and jayhawkers of both armies, and of neither. Horses and stock were stolen, houses burned and wayside murders committed. The people, observing old political lines fell into both armies, according to their traditions; but they seem not to have divided by any geographical line. Between rival families recriminations ensued after the peace, and in time old grudges began to be avenged, and bushwhacking was not uncommon.

- Dougan, Michael B. (1976). "7) The Second Year of the War". Confederate Arkansas - The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscalooosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780817305222.

In the Ouachita and Ozark mountains, where the war had been considered an alien imposition from the first, the threat of conscription intruded violently on the culture of the hill folk. Given the sturdy independence of the mountaineer and his propensity for violence, conscription gave an added impetus to bushwhacking and guerrilla warfare. Moreover the mores of this folk culture made it necessary for the mountaineer to seek revenge for each actual or alleged aggression. Thus the need of the Confederacy for manpower clashed head-on with traditional mountain ways. The results were murder, robbery, brutality, destruction, and lasting bitterness as mountaineers either hid in the hills, fled to the Federals, or, if taken, sought to desert at the first opportunity.

- Blevins, Brooks (Autumn 2018). "Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War that Refused to End". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Little Rock and Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 77 (3): 176. JSTOR 26554746. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- Brown, Walter L. (Winter 1961). "Dr. Thomas Russell: Founder of Russellville". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville, Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Association. 20 (4): 389. doi:10.2307/40030659. JSTOR 40030659. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

Dr. Russell and Mary Ann, with their two youngest sons, Thomas Jefferson and Lawrence, were refugees in Texas during the last months of the Civil War.

- Ragsdale, William Oats (1997). They Sought a Land : A Settlement in the Arkansas River Valley 1840-1870. Fayetteville, Arkansas: The University of Arkansas Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1557284983.

- Bishop, Albert W. (1867). Report of the Adjutant General of Arkansas, for the Period of the Late Rebellion, and to November 1, 1866. Washington D. C.: Government Printing Office. p. 94. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

(Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Cameron) As captain of company F, 2d Kansas cavalry, while on duty in Arkansas, in 1862-'63, I never failed to find faithful scouts and reliable guides among the citizens. When, at Dardanelle, during the months of November and December, 1863, with eighty-five armed men, ('Mountain Feds') surrounded by more than six hundred renegade Missouri rebels, I was sustained and re-enforced as often as necessary by the citizens of Pope and Yell counties, under the direction of Burk Johnson and the late William Stout, during which time over five hundred recruits were added to the federal army, and not a single case of treachery on the part of any citizen was discovered.

- Ragsdale, William Oats (1997). They Sought a Land : A Settlement in the Arkansas River Valley 1840-1870. Fayetteville, Arkansas: The University of Arkansas Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1557284983.

- Arsenault, Raymond (1988). The Wild Ass of the Ozarks : Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press in arrangement with Temple University Press (original publisher). pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780870495694.

- "Report of Major General Ord, Commanding Fourth Military District, September 27, 1867". Executive Documents, House of Representatives, 2nd Session of the 40th Congress, Vol.2. Washington, D. C.: U. S. Government Printing Office. 1868. p. 377. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- Reynolds, Thomas J (1908). "Pope County Militia War". In Reynolds, John Hugh (ed.). Publications of The Arkansas Historical Association, Vol. 2. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. pp. 174–198. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

In the spring of 1867 two companies of 'regulars' under the command of Major Mulligan, United States army, came to Dover, the county seat, to aid the civil authorities and in the interest of the Freedman's Bureau. These soldiers had a welcome reception and after a year and a half departed, regretted by all. The officers of the companies, by their gentlemanly bearing and conservative methods, made friends in every class of people.

- Singletary, Otis A. (Summer 1956). "Militia Disturbances in Arkansas during Reconstruction". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Little Rock and Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Historical Association. 15 (2): 142. doi:10.2307/40038001. JSTOR 40038001. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- "Arkansas's Iliad". The New York Herald. No. 13189. James Gordon Bennett Jr. September 30, 1872. p. 7. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

In this period, several county officials were killed, although the citizens disavow the acts, and say that they were private assassinations arising from personal causes.

- Bishop, Albert W. (1867). Report of the Adjutant General of Arkansas, for the Period of the Late Rebellion, and to November 1, 1866. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 121. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- "Pope". Daily Arkansas Gazette. March 8, 1870. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

On Tuesday night the jail was discovered in flames and in a few minutes was destroyed. The building had just been completed at a cost of $2500. The fire was evidently the work of an incendiary, as the locks were found in the flames with the bolts all drawn. There were four prisoners confined in the jail, all of whom escaped.

- "Pope County". Memphis Daily Appeal. Memphis, Tennessee. September 25, 1872.

- "Arkansas's Iliad". The New York Herald. No. 13189. James Gordon Bennett Jr. September 30, 1872. p. 7. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

After the new and disfranchising constitution went into operation a lull ensued, and for some time everything was quiet, but the county officials of Pope, who were all republicans and secret leaguers, grew more and more obnoxious to the people and both sides were surly, muttering and threatening. The native republicans, who go by the name of 'Mountain Feds' took sides with their Sheriff and County Clerk, and as the time of another election drew near the county authorities claimed that the insecurity of the times demanded martial law in Pope County.

- Affairs in Arkansas, Reports of Committees of the House Of Representatives, 2nd Session of the 43rd Congress. 1875-'75. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office. 1875. pp. 97–98. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

Deposition of William F. Grove, taken August 6, 1873...On arriving in sight of Dover I saw quite a number of armed men drawn up in the street, and on arriving in town found there between seventy and eighty men. I asked them why they were armed. They told me that Dodson had threatened to kill some of them and burn the town down. I asked them if they had any idea that he would kill any of them if he got them, or burn their town down. They said they did, for he had already partially carried out one threat by killing Hale and Tucker.

- "Affidavit of Perry West and G. W. Cox". The Missouri Republican. St. Louis, Missouri: George Knapp & Co. July 22, 1872. p. 3.

... on or about the 15th of April, 1872, John Williams, deputy sheriff, gave me orders to shoot or lead Nat Hale, John Hale, Reese Hogan, Harry Pointer, and John Young, saying, 'In fact, shoot any of them that impose upon you, come and give yourself up, and the governor will pardon you,' and he went so far as to say that he was going to get rid of the McCune and Hale outfit... The said John Williams said that he had orders to burn Dover, and he intended to do it.

Note: West and Cox were members of John Williams' militia company. - "Where should the county seat be located?". The Russellville Democrat. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. August 8, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- "Fine Cuts". The Russellville Democrat. No. 26 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. July 25, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- An Act entitled "An act to move the county seat of Pope County." (Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Arkansas (1873) ed.). Little Rock, Arkansas: Little Rock Printing and Publishing Company. April 25, 1873. p. 239. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- An Act to repeal An Act entitled An act to move the county seat of Pope County (Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Arkansas Passed at the 1874 Special Session ed.). Little Rock, Arkansas: Gazette Book and Job Printing Office. 1874. p. 7. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- "Personal interest and local feelings". The Russellville Democrat. No. 30, 12th year. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. September 1, 1886. p. 2. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "The Court House 'Gone Up'". The Russellville Democrat. No. 8 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. March 14, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "Come. Let Us Reason Together". The Russellville Democrat. No. 32 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. August 29, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "Here it is 'In Black and White' - Russellville Means to do Just What She Says". The Russellville Democrat. No. 32 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. August 29, 1878. p. 1. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "Circuit Court". The Russellville Democrat. No. 35 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. September 25, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

The village church was being used as a court house.

- "Removal of the Countyseat". The Russellville Democrat. No. 31 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. August 22, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "Judge Jacoway's Decision". The Russellville Democrat. No. 23 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas. The Russellville Printing Association. June 26, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- "Removal of County Seat". The Russellville Democrat. No. 18 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. May 22, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "$10,000". The Russellville Democrat. No. 22 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. June 19, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- "Supreme Court Decision". The Russellville Democrat. No. 25 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. July 17, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- "An Act to be Entitled An Act to Provide for locating and Changing of County Seats". The Russellville Democrat. No. 29 Vol IV. Russellville, Arkansas. The Russellville Printing Association. August 8, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

... unlawful to establish or change any county seat, in this State without the consent of a majority of the qualified voters of the county to be affected by the change...

Note: Approved March 2, 1885 - "Judge Jacoway's Decision on the County-seat Question". The Russellville Democrat. No. 37 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. October 9, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- "Report of the Grand Jury". The Russellville Democrat. No. 37 Vol V. Russellville, Arkansas. The Russellville Printing Association. October 9, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

We consider the Court House as a very unsafe place to keep the public records in, and liable at almost any time to fall to the ground—rendering It not only unsafe for the public records, but hazardous to the life of those who have to be about the building. We would recommend that the records be removed to a safe place. We condemn the building as wholy unfit for use as a Court house.

- "Local News". The Russellville Democrat. No. 48 Vol VI. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. December 23, 1880. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

...Mr. W. T. Cox, to whom was awarded the contract for repairing the court house at Dover... will soon commence work on the building.

- "Dover Dots". The Russellville Democrat. No. 6 Vol VII. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. March 10, 1881. p. 3. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

The repairs on the court house are moving up lively...

- "Dover Dots". The Russellville Democrat. No. 46, Vol VI. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. December 9, 1880. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

The contract for repairing the court house was let... to Mr. W. R. Cox, of Atkins, for $1000, his being the lowest bid. The work according to contract and specifications will commence at once and is to be completed by the March term of the circuit court.

- "Proclamation of Election in the Matter of County Seat Removal". The Russellville Democrat. No. 27, 12th year. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. August 4, 1886. p. 3. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "Proclamation of Election in the Matter of Location of the County Seat". The Russellville Democrat. No. 5, 13th year. Russellville, Arkansas. February 23, 1887. p. 2. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "Adkins Bond—$50,000". The Russellville Democrat. No. 30, 12th year. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. September 1, 1886. p. 2. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- "Russellville's Majority 128". The Russellville Democrat. No. 9, 13th year. Russellville, Arkansas. The Russellville Printing Association. March 23, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "County Seat Removal". Daily Arkansas Gazette. No. 185, 86th year. Little Rock, Arkansas: The Gazette Printing Company. June 19, 1887. p. 6. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

"But it is a universal rule that the donating of facilities for the public convenience, as an inducement to the electors to vote for the removal of a county seat, will not invalidate the election. Affirmed.

- "Neal v. Shinn, 49 Ark. 227 (1887)". Case Law Access Project. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Law School. June 4, 1887. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "The Court House Question". The Russellville Democrat. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. March 30, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

The case appealed to the supreme court has not been decided...

- "Court House Meeting". The Russellville Democrat. No. 21, 13th year. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. June 15, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- "Laying of the Corner Stone of the Court House of Pope County". Russellville Democrat. No. 37, 13th year. Russellville, AArkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. September 28, 1887. p. 2. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- "Court House". The Russellville Democrat. No. 30, 13th year. Russellville, Arkansas. The Russellville Printing Association. August 10, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- "It is Finished". The Russellville Democrat. No. 17, 14th year. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. May 17, 1888. p. 3. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "Norristown". Russellville Democrat. Russellville, Arkansas: The Russellville Printing Association. July 20, 1876. p. 3.

A quiet little village..., some 3 miles from the station of Russellville... For many years Norristown was the principle mercantile point of the county. Since the completion of the L. R. & F. S. Ry. most of the business men have left the place and removed to Russellville. It is still a quiet, pleasant little town.., with a population of 100 or 150 souls.

- "Russellville Downtown Historic District". National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

On the night of January 16, 1906 a fire destroyed nearly half of the downtown business district. The fire included both sides of Commerce Street from Main to "B" Street. Ironically, Russellville had just formed a fire department and ordered fire-fighting equipment, all of which had not arrived. The newly formed fire department, insufficiently organized, was helpless to contain the ravaging fire which, fueled by strong winds, spread to the north side of Main Street from Commerce. In less than three hours, twenty-three buildings were destroyed. The estimated loss was $250,000 of which only 40% was insured. In addition to the loss of the buildings and their stock, many of the citizens of Russellville who worked in the businesses abruptly lost their jobs. Those early businessmen of Russellville immediately set about re-building the downtown and, remarkably, within six months, twenty of the twenty-three buildings lost in the fire had been rebuilt.

- "Russellville Downtown Historic District". National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

In 1931 a new courthouse for Pope County was constructed on the site of the original 1888 building. The four-story brick building was designed by Arkansas architect H. Ray Burks (architect of many Arkansas county courthouses) and is typical of Depression-era public building construction with its simple lines and Art Deco detailing.

- "Pope County Courthouse". SAH Archipedia. Society of Architectural Historians. November 6, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

This courthouse, which replaced an 1888 structure, is the dominant building in the downtown. It occupies a small corner site, presenting two facades, of which the principal and more elaborate one faces Main Street. Constructed of beige brick, the courthouse is three stories in height on a raised basement and is elaborated with fluted pilasters of white between the windows and flanking the main entrances. The entrance to the building on the Main Street side is handsomely decorated with low relief Art Deco stylized foliate ornamentation, a cartouche, and, perched on the entrance entablature, a sculpted eagle with outstretched wings.

- Robinson, Kat. "Oh How I Love Thee, Rotary Ann". Tie Dye Travels. Kat Robinson. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Bruner, Ernest. "History of Rotary Ann". Rotary Club of Lake Houston Area. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

In many Rotary clubs throughout the world, wives of male members are affectionately called "Rotary Ann's." This designation was never one of disparagement, but rather grew out of an interesting historical occasion.

- "Bossier Firm Bids Low on Arkansas River Work". Boosier City Planters Press. No. 50, Vol XXIV. Bossier City, Louisiana. Planters Press Publishers, Inc. June 4, 1953. p. 1. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- Reynolds, Henry (December 1, 1957). "Holla Bend to become National Wildlife Area-Hunters Hope For the Best". The Commercial Appeal. No. 335, 118th year. Memphis, Tennessee: The Memphis Publishing Company. p. 29. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- "Holla Bend Island, Arkansas, Becomes National Wildlife Refuge" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Department of the interior Information Service. September 1, 1957. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

The land was transferred without cost to the Department by the General Services Administration pursuant to the provisions of Public Law 537, 80th Congress.

- "Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge - Abbout Us". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Department of the interior. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

In 1957, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers transferred 4,068 acres to the Fish and Wildlife Service, but retained a permanent flood easement for these acres. In 1985, a court action based on the Thalweg Law accreted an additional 1,526 acres for the refuge. Other acquisitions totaling 589 acres, plus 441 acres included in the migratory bird closure area, account for a total of 7,055 acres currently under refuge management.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "East Fork Wilderness". USDA Forest Service. U. S. Government. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

The East Fork Wilderness takes its name from the East Fork of the Illinois Bayou, which bisects the wilderness from the northeast to southwest. The Area encompasses 10,777 acres along the southern edge of the Boston Mountains. East Fork's terrain is characterized by flat or gently rounded ridges separated by hollows with very steep slopes of sheer rock walls. The elevation ranges from 800- 1,600 ft. The most unique feature of East Fork Wilderness is the presence of 3 upland ponds. These areas have exposed standing water during wet weather months and...

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Based on 2000 census data

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- 2011 Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS): Pope County, AR (PDF) (Map). U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- "Arkansas: 2010 Census Block Maps - County Subdivision". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 28, 2014.