50th (Northumbrian) Division

The Northumbrian Division was an infantry division of the British Army, formed in 1908 as part of the Territorial Force with units drawn from the north-east of England, notably Northumberland, Durham and the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire. The division was numbered as 50th (Northumbrian) Division in 1915 and served on the Western Front throughout the First World War. Due to losses suffered in the Ludendorf Offensive in March 1918 it had to be comprehensively reorganized. It was once again reformed in the Territorial Army as the Northumbrian Division in 1920.

| Northumbrian Division 50th (Northumbrian) Division | |

|---|---|

Division sign as used on signboards.[1] | |

| Active | 1908–19 March 1919 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Peacetime HQ | Richmond, North Yorkshire |

| Engagements | Western Front (World War I) |

Formation

The Territorial Force (TF) was formed on 1 April 1908 following the enactment of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907 (7 Edw.7, c.9) which combined and re-organised the old Volunteer Force, the Honourable Artillery Company and the Yeomanry. On formation, the TF contained 14 infantry divisions and 14 mounted yeomanry brigades.[2] One of the divisions was the Northumbrian Division.[3]

The divisions were intended to be replicas of the regular army divisions of approximately 18,000 men on mobilisation including infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineer, medical, supply and signal units. The Northumbrian Division was typical, consisting of three infantry brigades, the 'Northumberland', 'York and Durham' and 'Durham Light Infantry (DLI)' Brigades. Each brigade was composed of four infantry battalions, descendants of the local Volunteer corps. In 1907 Lieutenant General Robert Baden-Powell was appointed to command the division;[lower-alpha 1] he held command from April 1908 to 1910.[4] In peacetime, the divisional headquarters was at Richmond Castle in Richmond, North Yorkshire.[3][5]

The terms of the Territorial Force soldiers were for home service only; they were to be used to garrison the country when the regulars left for overseas. In the summer of 1914 the division was at its annual summer training camp in North Wales when, on 3 August, it received orders to return to the North East. Receiving mobilisation orders the next day, the division arrived at its war station of the coastal defences, railways and dockyards of the Tyne and Wear area. After preparing these defences and undertaking more training, the Territorials volunteered to serve overseas in September.[6] After more training the division was the fourth to be declared fit for service,[7] embarking for France between 16 and 19 April 1915 with orders to concentrate around Steenvoorde.[8]

World War I

A new division arriving in France would normally expect a period of additional training to teach the men about Trench warfare, however on the evening of the arrival of the last unit on 22 April, the division was ordered to have all units stand by.[9]

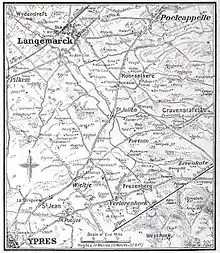

Second Battle of Ypres

St Julien

In the early stages of this battle, the separate brigades and even battalions were to come under command of other divisions, the 4th, 5th, 27th and 28th British divisions and the 1st Canadian Division. The brigades were committed piecemeal to the battle with the York and Durham brigade the first to come under fire at first light on 24 April,[10] before moving into the GHQ line. Two battalions of the brigade (1/4th Green Howards and 1/4th East Yorkshire Regiment) were the first of the division to attack the Germans, attempting to take St Julien in the afternoon, but being beaten back and returning to Potijze in the dark.[11] The Northumbrian and DLI brigades were moved up to Potijze that evening. The 6th DLI was sent to the GHQ line, and the 8th battalion began a long trek in the rain via Zonnebeke to relieve the 8th Canadian battalion at Boetleer's Farm on the Gravenstafel ridge, arriving in the early hours of 25 April.[12]

The Northumbrian and York and Durham Brigades were to be the Corps reserve for an attack on St Julien on 25 April. Two battalions of the York and Durham Brigade (1/5th Green Howards and 1/5th D.L.I.) and the four of the Northumbrian Brigade supported the attacks of the 10th Brigade, but, due to poor communications and timing errors, gained little but casualties from artillery.[13] The 8th D.L.I. (with a company of Monmouths and one of the Middlesex Regiment) at Boetleer's Farm, suffered almost constant shelling throughout the day, some of it from the rear from the southern end of the salient, but held on to repulse a German attack in the evening. Early the next morning the exposed position, North of the Gravenstafel—Koorsaelaere road, was flanked and the battalion suffered from machine-gun fire in enfilade, and was forced to fall back by sections, even then stopping the German advance with rifle fire, reaching a more established line and the reinforcements that had been promised earlier, late in the day.[14] The battalion was reduced to 146 officers and men.[15] The 6th and 7th D.L.I. were used to support the 85th Brigade around Zevenkote and Zonnebeke, and were shelled throughout the day.[16]

The Northumberland Brigade was to suffer once more from poor communications on 26 April. Concentrated around Wieltje, the brigade was designated the reserve for the 1st Canadian Division. In the morning the 5th N.F. was ordered to reconnoitre and block a possible German attack from Fortuin, reaching the village, it came under artillery fire and dug in.[17] At 1:30 pm orders were received for the rest of the Brigade to attack St. Julien in cooperation with the Lahore Division and 10th Brigade, this was the first attack by a territorial brigade in the war. With only 35 minutes in which to prepare before the start of the attack, no artillery support was obtained and the routes through the wire of the GHQ line were unknown, as a result the troops were slow in leaving and presented targets for the Germans. On reaching the front line the 10th Brigade could not be found, its orders had been changed. Advancing from here the 6th N.F. took some trenches the Germans had retired from, the 4th and 7th battalions were unable to leave the front line. Under artillery fire the 6th battalion dug in and withdrew during the night. The Northumberland Brigade lost 1,954 officers and men, over 2/3 of its strength, during the day.[18]

The next few days were spent preparing the new line to which the allies were to fall back to, and alternately holding the front line, often reinforcing other units in company strength, all the while under fire. The infantry of this novice and unacclimatised Division was withdrawn from the salient during the night of 2–3 May, having lost 3764 men killed, wounded and missing since 24 April.[19] On 5 May the 5th (Cumberland) Battalion of the Border Regiment joined the Northumbrian Brigade to reinforce it.

Frezenberg Ridge

The next German attack, on the Frezenberg Ridge, began on 8 May and for the first time involved the division's artillery under the control of the other British Divisions in the area (the 4th, 27th and 28th). The Howitzers firing from positions West and North of Ypres and the field guns from south of Potijze revealed the age and limitations of the 4.7-inch guns, and 15-pounders. The infantry would be used to provide working parties, with the Durham Light Infantry Brigade (6th, 7th and 9th battalions) moving into the 2nd line trenches on 11 May astride the Menin Road, and the 5th Green Howards and the 5th D.L.I. being split into companies and attached to Regular battalions near Sanctuary and Hooge Woods. None of the infantry was involved in fighting.[20] On 12 May the division HQ was informed that it was now to be known as the 50th (Northumbrian) Division, and its infantry Brigades numbered as the 149th, 150th and 151st, and artillery Brigades 250th, 251st, 252nd and 253rd.[21] The artillery would remain attached to other divisions in action around Ypres until the end of the month.[22]

Bellewaarde

The infantry of the division continued its dispersed existence to the extent that some battalions were split into companies and attached to different battalions of other divisions in the line, even the division history admits difficulty in following them.[23] The brigades of the division were used to reinforce the regular units in the line, (from North to South) the 149th brigade with the 4th Division around Verlorenhoek, the 151st with the 28th Division, West of Bellewaarde, and the 150th with the Cavalry Corps[lower-alpha 2] near Bellewaarde lake and the Menin Road.[25]

In the early morning of 24 May the Germans launched an intense artillery and gas attack on the British lines, even those units not in the front line suffered from the gas. In some areas of 4th Division's line the German trenches were only 30 yards away, for example at Mouse Trap Farm, and surprise was gained, forcing the British back to reserve lines. Here the 5th Borderers and 5th N.F. were very much distributed among 10th and 12th Brigades.[26][lower-alpha 3] The 5th Northumberland Fusiliers lost 24 dead, 90 wounded and 170 missing, while the 5th Borderers simply state in their history that they had heavy casualties to gas but difficulty in numbering them due to the dispersion.[27] The trenches in the line held by 85th Brigade (28th Division) were in a poor state due to the weather, and here the Germans broke through the front line between the Potijze—Verlorenheok road and the Ypres—Roulers railway.[28] Two companies of the 9th D.L.I., attached to the 2nd East Surreys, found themselves of the North shoulder of the breakthrough, with two companies of the 7th D.L.I., attached to the 3rd Royal Fusiliers, on the Southern, which was attacked again and forced back to rear lines. The 8th D.L.I. (now 275 of all ranks strong) was ordered to reinforce this Southern section and close the gap and after being shelled moving up through the GHQ line, succeeded in surprising the Germans and rushing 200 yards of open ground without loss to do so.[29]

Holding the Line

On 1 June the division HQ learned that it was to take over a section of the line as a whole division, the first time since 22 April. It first had to reassemble, which was completed on 5 June, concentrating at Abele.[30] On 7 June, the 150th Brigade took over from 9th Brigade (3rd Division) in the trenches West of Zillebeke.

...It [the trench] lay along a ridge of a small hill [Mount Sorrel] and so it was well drained. It was also pleasantly deep so that one had not to walk about half doubled up. I believe the trench was originally dug by the French, as there are a lot of their graves around here. The odour suggests that they were not buried very deep!

— Officer of the 5th D.L.I., [31]

They were joined by the 149th Brigade on 10 June to their North up to the Menin Road, with the trenches separated at Hooge by only 15 yards.[32] There began the never-ending task of trench repair and strengthening, shared by 151st Brigade in the reserve lines around Maple Copse, "...notorious for being the meeting place for half the stray bullets in the district.".[33] Due to losses sustained by the 8th Durham Light Infantry in April and May, it had been merged with the 6th battalion to form the composite 6th/8th Battalion on 8 June, and on 11 June the 1/5th Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment was attached to the brigade to bring it up to strength.[34] On 16 June the division's artillery supported an attack by 3rd Division on the German lines at Bellewaarde,[lower-alpha 4] with the infantry also supporting with rifle fire from their lines. The 7th Northumberland Fusiliers were trench mortared in their trenches which were too close to the Germans for artillery support.[36]

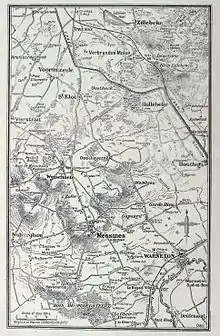

Between 21 and 24 June the division transferred to the line around Messines and Wytschaete, all three brigades would be in the line, in order from South to North, with two battalions in the front line.[37] Part of the 149 and 150th Brigades' lines near the River Douve were breastworks. This part of the line was considered to be quiet compared with the Ypres salient, but still included artillery duels, trench mortaring, grenades, sniping, mining and patrolling no-mans-land. The division still considered it a rest.[38]

After a month the division was sent to the Armentieres sector, another relatively "quiet" sector,[lower-alpha 5] arriving between 17—18 July.[39] On 7 August the 6th/8th Battalion Durham Light Infantry was separated back into two battalions, coming under separate command on 11 August.[40] In September the division's artillery supported the opening of the Battle of Loos, the infantry also demonstrated on the front line to (unsuccessfully) deceive the Germans.[41] In early November the old 15-pounders of the artillery were replaced with new 18-pounders, and the worn out 4.7-inch guns replaced with new 4.5-inch howitzers.[42]

On 12 November the division was taken out of the line for training and concentrated in the Merris—La Crèche area.[43] On 16 December the 7th Durham Light Infantry was converted into the division's pioneer battalion, with the 5th Borderers transferring from the now replenished 149th Brigade into the 151st Brigade, the 5th North Lancashire Regiment was to leave the division for the 55th (West Lancashire) Division in late December.[44]

The Salient

In early December the division received orders that it was to return to the Ypres Salient and join V Corps and relieve the 9th (Scottish) Division between the Menin Road and Hill 60. The initial deployment of three battalions into 9th Division area on 17 December coincided with a gas attack.[44] The relief was completed on the night of 20–21 December, with two battalions of each brigade in the line, suffering casualties from the flanking German bombardment of an attack on the 6th and the 49th Divisions[45] The artillery was positioned North, West and South of Zillebeke Lake, the position of the 1st Northumbrian Brigade described as follows:

For honest filth and disgusting conditions it would be hard to beat...There was an excellent academy picture of an aeroplane flight above, i.e., 1916 or 1917, and I was interested to see that our position was shown by the artist as a cloud of dust and bursting shells, which we found very true to life.

— Colonel Shiel, 50th Division Artillery, [46]

The now wrecked field drainage system caused the buildup of thick mud in all areas and Trench foot made its appearance in the division.[47]

1916 was ushered in by all guns of the division's artillery with a five-minute barrage of the German trenches, there was no reply. In late January the division's line was reduced to a two brigade front with the 149th Brigade initially going into reserve.[48] Since their time in Armentieres, the division had aimed to have the last word in any exchange of grenades or trench mortars, returning double the number of rounds on any occasion. This was maintained in the Salient, together with the domination of no-man's land by patrolling.[49] At this time the operations in the Salient were of a small scale and consisted of repulsing local German attacks, mining operations and occasional demonstrations aiding attacks by neighbouring divisions. Between late March and April 1916, the division was relieved by the 1st Canadian Division and in turn relieved the 2nd Canadian Division in the Wytschaete area. The last Brigade to leave, the 151st, was shelled by the Germans in part of the actions around the St. Eloi craters.[50]

The division again deployed on a three brigade front, with both sides rear areas under observation from high ground behind each line. The Canadians had described the sector as a quiet one, however, after the blowing of the St. Eloi mines to the left of the sector, the amount of trench mortaring greatly increased.[51] At the end of April the division went into Corps reserve, with the Headquarters at Flêtre, the division's artillery was reorganised and renumbered during this time.[52] At the end of May the division returned to the same part of the line, relieving the 3rd Division. During its time there, in addition to strong patrolling in no-man's land, the division's first recorded trench raids took place.[53] The first raids, by 4th East Yorkshires and the 4th Green Howards on the night of 26 June were infective due to the poor placement of the covering barrage.[54] The first successful raid, by the 5th Green Howards, took place on 10 July in a mine crater used by the Germans as part of their front line.[55] Thereafter raids were frequent and rarely returned. On 9–10 August the division was relieved by the 19th (Western) Division, and transferred to the Montigny-en-Gohelle area for training, as part of III Corps, arriving on 17 August.[56]

The Somme

The training was short lived for the artillery, on 19 August two brigades, the 251st and 253rd, relieved the 34th Division's artillery, who were covering the 15th (Scottish) Division's line at Contalmaison.[57] The remainder of the division took over a section of the 15th Division's line North and North-East of Bezin-le-Petit on 9 and 10 September, with the 149th and 150th Brigades in a section of the line protruding some 250 to 300 yards from the rest of the line, with the 15th Division on the left and the 47th (1/2nd London) Division to the right.[58] On 11 September Brigadier General Clifford, the commander of 149th Brigade was killed by a sniper.[59]

The Battle of Flers–Courcelette

On 15 September the division took part in the third offensive on the Somme, its first 'set piece' battle. With 150th brigade of the left and 149th on the right, the division was set objectives of German trenches (named Starfish and Prune) between Martinpuich and High Wood.[60] With the aid of a creeping barrage and two tanks on the left flank, the assaulting battalions quickly gained the first objective. Most of the second line was also gained, but casualties to both brigades during the advance were much heavier due to flanking fire from Martinpuich and High Wood. The advance continued towards the third objective, with intermediate trenches being gained in the afternoon. That evening the 151st brigade was sent into battle for the final parts of the line but could make no progress.[61] Over the next few days attacks were made which varied in their success, and with the relief of the 150th brigade by the 69th brigade of the 23rd Division, the 151st brigade was left in the line, in the increasingly wet weather, with, in places, two and a half feet of mud in the trenches. On 21 September the 149th brigade finally achieved the German lines that were the original third objective, after the Germans had withdrawn.[62] The division had suffered 3750 casualties of all ranks, by 24 September, 149th brigade had been withdrawn to Divisional reserve, 150th Brigade was in the line and the 151st in support.[63]

The Battle of Morval

Remaining in place but now flanked by the 1st Division and the 23rd Division, the 50th played a limited role in this battle, the first objective had already been taken by patrols of the 5th Durham Light Infantry, before the start of the attack on the afternoon of 25 September.[64] The remainder were taken in piecemeal attacks, with the only large scale casualties occurring on the night 26–27 September during a night advance. On that occasion the 5th Green Howards alone reached a German trench, but were bombed back out of it, as the supporting flanks became lost.[65]

The Battle of Le Transloy

By the end of September the 151st brigade was in the line, with the 149th in support. The 5th Borderers and 6th Durham Light Infantry were so depleted that they were formed into a composite battalion for the next attack on the German's Flers line, with the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers moving up to the line.[66] In the afternoon of 1 October the advance was made behind a creeping barrage, and the first German line reached with few casualties, and the composite battalion taking the German support trench. Only on the right, where the 6th Durham Light Infantry were on an open flank, was there more fighting, they were ejected from and then regained the first line.[67] Reinforced that evening by the 9th Durham Light Infantry, the first line was held and the second taken at 1a.m. on 2 October. During this action the 9th's C.O., Lt. Colonel Roland Boys Bradford won the V.C.[68] On 3 October the division was relieved by the 23rd Division, and marched to Millencourt, except for the artillery, engineers and pioneers, which remained to support the 23rd.[69]

During the rest and refitting of the division, the front continued to advance, and in the area the 50th had operated, La Sars was captured on 7 October. The 50th Division returned to the line, taking over from the 9th Division on 24 October, with the 149th and 150th brigades in the front line trenches.[70] By now the weather had turned and conditions in the trenches were deteriorating:

Cold, damp day; mud sticky and plentiful.

— extract from the 50th Division Diary (26 October)[71]

The Butte de Warlencourt

In front of the line lay an otherwise unremarkable chalk outcrop, the Butte de Walencourt, which gave some observation over the rear of the British lines in that area. This was to be the object of the next attack. The main German front line (named 'Grid' by the British) ran behind the butte, with another trench in front ('Butte').[72] The heavy rains and consequent muddy ground forced postponements of the attack originally planned for 26 October to the 28th, then 1 November, then the 5th. By this time the German artillery and the difficult conditions had exhausted the brigades in the front line and on 4 November the 151st Brigade relieved the 149th.[73] Heavy rain again fell on the night of 4–5 November, and when the advance began the mud reduced it to a literal crawl behind the creeping barrage. Both flanks of the advance took flanking fire by machine guns, and on the right, 8th Durham Light Infantry also took hits from 'shorts' from British trench mortars and artillery, it was stopped in front of 'Butte' trench and forced back.[lower-alpha 6] In the centre the 6th Durham Light Infantry had mixed fortunes, the right suffering in the same manner as the 8th, while the left succeeded in establishing a block in the 'Grid' trench. On the left, by mid morning the 9th Durham Light Infantry had taken a quarry to the West of the butte, and a section of 'Grid' trench to the East and later another West of the butte. In the afternoon the Germans counterattacked, using artillery to prevent reinforcement from the British lines, and the 9th battalion, with part of the 6th and a section of the Brigade machine gun Company held out until evening when they were forced back to their start lines. The infantry battalions of the 151st Brigade lost 967 men of all ranks, killed, wounded or missing and with the pioneers and machine gun companies the losses approached 1000.[75]

On 14 November the division was ordered to attack a site of German trench building near the butte. The 149th Brigade succeeded in gaining part of the 'Grid' line and holding it overnight, but were repulsed after heavy counterattacks throughout the next day. The brigade and supporting units suffered 889 men killed wounded or missing.[76] By 20 November the division had been relieved by the 1st and 48th (South Midland) Divisions.[77]

After supplying work details to the rear areas and to the town mayor of Albert, on 1 December the division moved to the Baizieux area and began training.[78]

The first day of the new year of 1917 saw the division return to the Somme and took over the line to the right of its previous battles, relieving the 1st Division. Only the artillery was active, with the infantry of both sides battling the weather:

You have no idea of the state of the ground near these advanced posts. Wherever one looked, one saw the same endless extent of black mud and water, christened all over the place with the remains of old trenches and wherever one walked, one slipped or slithered about among the innumerable shell holes. Almost every day both British and Bosche lose their way and get into the enemy lines...Wandering about in the mud at night was rather an uncanny business as there were a great many dead bodies lying about, some already half sunk in the mud. The mud will have swallowed them all up before the winter is over.

— An officer of the 50th Division.[79]

The division artillery was reorganised, with the 252nd Brigade broken up and distributed amongst the remaining Brigades.[80]

Relieved by the 1st Australian Division on 28 January, after a short rest the division was deployed South of the Somme on 16 February near Foucaucourt.[81] Again the sector was relatively quiet, with trench raids beginning only in March when it was learned that the Germans, in other sectors, were retiring to the Hindenburg Line. On 5 March the division was relieved by the 59th (2nd North Midland) Division (the artillery remained until 23 March, and on 25 March was transferred to VII Corps to assist with the bombardment for the Arras battles), and transferred to Méricourt for training. By 8 April the divisions had moved to the Avesnes area.[82]

The Battle of Arras

The division's artillery was in action on the Arras front from 2 April under the orders of 56th (London) Division around Beaurains and Agny, and on the night of 8–9 April used gas shells for the first time.[83]

First Battle of the Scarpe

The assault began on 9 April, with the division, 149th and 151st Brigades in the front line, relieving the 14th (Light) Division on 11 April, immediately east of Wancourt, flanked by the 56th (on the right) and 3rd Divisions. On 14 April the 151st brigade advanced to capture high ground East of Héninel and a height, the site of Wancourt Tower which had collapsed on 13 April. Fighting would continue around the height, until it was captured by the 7th Northumberland Fusiliers on 17 April.[84]

Second Battle of the Scarpe

On 23 April the 150th Brigade, with 151st Brigade in support, was given the task of capturing the ridge to the East of Wancourt as a first objective and secondly, further ground up to the village of Cherisy.[85] The advance was supported by two tanks, however the troops ran into their own creeping barrage and were also shelled by the Germans. The leading battalions (4th East Yorkshires and 4th Green Howards reinforced by two companies from the 5th Durham Light Infantry) reached the initial objective but both battalions had open flanks and were soon subject to counterattack. At one point the 4th East Yorkshires were surrounded, but both battalions managed to regain the British lines. Captain Hirsch won the V.C. for his actions. Both flanking divisions, the 15th and the 30th, had also been forced back to their starting lines.[86] That evening another attack was launched, with the 150th Brigade reinforced with the 5th Borderers and 9th Durham Light Infantry from the 151st Brigade. This attack regained that morning's objective, on a 1600-yard advance on a 500-yard front, as well as recovering numbers of British wounded in German hands from the morning, and in turn taking prisoners. Casualties that day were 1466 officers and men killed, wounded and missing.[87]

After being relieved by the 14th Division, except for the artillery which remained behind to support it, the division moved into reserve around Couturelle.[88] On 2 May the division was placed in reserve for the Third Battle of the Scarpe, West of Wancourt, but did not participate.[89]

Apart from a 4 days in the line for the 149th Brigade, relieving the 33rd Division near Saint-Léger, the division was rested and trained until mid June, when it returned to the Arras front and relieved the 18th (Eastern) Division near Chérisy.[90] The division's artillery returned to its command, as well as, initially, a brigade from each of the 33rd and 56th Divisions and all of the 18th Division's artillery.[91] With the improvement in the weather and ground conditions, patrolling and trench raiding by both sides was vigorous, until the division was relieved in early October by the 51st Division.[92]

By 23 October the division was once more in the Salient, relieving the 34th Division on the Ypres—Staden railway, with the 149th brigade in the front line supported by the 150th.[93]

The Third Battle of Ypres

Fifty square miles of slime and filth from which every shell burst threw up ghastly relics, and raised stenches too abominable to describe; and over all...the sickly reek of deadly mustard gas.

— Artillery officer of 50th Division.[94]

The already difficult terrain was made even more so by rain on the night before the attack, and on the morning of 26 October the 149th Brigade was unable to keep up behind its creeping barrage. A double line of concrete bunkers protected the objective, and were untouched by the shrapnel shells used in the barrage, and although some German trenches were reached the men in these attacks were killed or driven back to a line 150-yard in front of the start line. When relieved by the 150th Brigade that night, the 149th Brigade had lost 1,118 officers and men killed, wounded or missing.[95] Relieved on 9 November by 17th (Northern) Division, the division returned to the line on 13 December, relieving the 33rd Division East and South of the featureless remains of Passchendaele village. It was relieved after a relatively quiet time on 5 January 1918 by the 33rd Division.[96]

Reorganisation

In February 1918, the army's divisions were reorganised from four infantry battalions per brigade to three, as the result of manpower shortages, caused in part by the British government's reluctance to send new recruits to be "wasted" on the Western Front.[97] None of the division's battalions were disbanded, but it lost the 7th Northumberland Fusiliers to the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division, the 5th Durham Light Infantry transferred from the 150th Brigade to the 151st, from which the 5th Borderers and the 9th Durham Light infantry left the division, both to become pioneer battalions in the 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division and the 62nd Division respectively.[98]

In late February the division was again relieved by the 33rd Division. Training was carried out in the Wizernes area until early March when the division transferred to South of the Somme in Fifth Army reserve.[99]

Spring Offensive

It had been known since the Russian ceasefire that the Germans would use the troops freed from the Eastern Front to launch an attack on the West.[100] Preparations were begun for a defence in depth but were incomplete by the time of the first assault.[101]

The division was to be particularly unfortunate that Spring in being caught in three of the German's assaults, together with the 19th, 21st and 25th Divisions.[102]

The First Battles of the Somme, 1918

The division arrived in the area of Harbonnières on 9 March, on 12 hours notice to move while it conducted training.[103] The division's engineers and pioneers had been sent forward on 15 March to assist with XIX Corps defence works. The assault, aided by thick fog, began on the morning of 21 March, and the division was ordered into the rear "Green" line of defences between Péronne and St Quentin, North of and straddling the Roman road around Poeuilly, arriving exhausted after a long march early on 22 March and deploying all three brigades in the line. During the morning and early afternoon the 24th and 66th Divisions retired through their line, and at 4 p.m. the first German assaults began. The attack fell on all brigade fronts with some battalions being forced back, with the reserve battalions used to maintain a continuous front. The order to retire from the Green line was given in the evening, and next morning more orders to retire even further were received. But before the new line could be established, and while rear guards fought with the advancing Germans, more orders were received to withdraw to the Somme river.[104] After at times heavy fighting the increasingly tired men of the division crossed the Somme at Éterpigny, Brie and St. Christ-Briost through the 8th Division.[105]

On 24 March most of the division occupied defensive line some 3 miles West of the Somme, around Assevillers and Estrées-Deniécourt.[106] By now the brigades of the division were under orders of the 8th Division (150th and 151st Brigades and the Pioneers, 7th Durham Light Infantry, fighting as infantry) and 66th Division (149th Brigade), and later the 20th Division (150th Brigade). Over the next two days continued infiltration and exposure of flanks by the advancing Stormtroopers caused the retreat of 50th Division troops to line from Chaulnes to Curlu on the Somme.[107] The fighting was such that on the afternoon of 25 March, due to losses, 150th Brigade was reformed into a single composite battalion with a strength of around 540 officers and men.[108] The next day, 26 March, the division, now with 149th Brigade reattached, fell back under orders and a closely following German attack to between Rosières-en-Santerre and Vauvilles, along with 150th and 151st Brigades, still under 8th Division. German attacks on this line on 27 March were stopped, opposite Vauville however confused orders caused a withdrawal by part of the 149th and 151st Brigades, who later counter-attacked and regained the lost ground.[109]

Over the next few days further orders to withdraw were received, with the Germans always in close pursuit, first to a line between Caix and Ceyaux and then between Mézières and Demuin. The increasingly tired troops managed a counterattack on 30 March with the 150th Brigade composite battalion driving the Germans (by this time equally tired) from Moreuil Wood.[110] The last gasp of the German offensive pushed the troops of 50th Division over the river Luce on 31 March, and on 1 April the division began to be relieved.[111]

Apart from the heavy casualties, the worst feature of the Somme fighting was undoubtedly the incredible fatigue and lack of sleep. Men simply could not keep awake despite the danger, and the slightest respite found them in deep slumber. Any bed was a good bed—a heap of stones by the roadside, a ditch, an open field, a sloping bank. Cold and hunger were forgotten in Nature's overwhelming clamour for sleep. Passing through Moureuil on the eve of Good Friday, men dropped asleep on doorsteps for three or four minutes, walked a few yards further, slept on another doorstep and so on.... Physically the men had come to the very end of their tether—only sheer will power kept them going.

When reassembled in the Douriez area the division, excluding the artillery, which remained in the line defending Amiens, numbered about 6000 all ranks.[113]

Battle of the Lys (1918)

A German attack in this area had been thought possible since before the Somme offensive, however when that battle began ten divisions had been moved South from the Ypres salient. In return only tired and depleted divisions were returned, the 50th among them.[114]

The division was reinforced to some degree by new recruits from the various regiments' graduated battalions, veterans 'combed out' from various depots and numbers of hastily reclassified 'category B' men. Unable to be replaced were the large numbers of experienced officers and N.C.O.s lost during the Somme battle.[115] By 7 April the division was part of XV Corps part of the reserve of the First Army, with the 151st Brigade at Estaires and the rest of the division at Merville during the planned relief of the 2nd Portuguese Division of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps.[116]

The German attack began on 9 April forcing back the Portuguese, the 151st brigade advanced to La Gorgue and Lestrem, and at midday contact was made with the enemy at Leventie by 6th Durham Light infantry. The 150th Brigade was moving up to the river Lys at Estairs and the 149th Brigade to the North. By the evening the 6th Durham Light Infantry had been pushed back to the Lys, and had been reduced to four officers and 60 men, with only small bridgeheads at the bridges over the river. The 8th Durham Light Infantry holding a series of posts in company or platoon strength on the river Lawe around Lestrem, had its posts overrun with only small numbers escaping back to the Lys by the evening.[117] The 149th and 150th Brigades prevented the Germans from advancing across the Lys, and that night the bridges held by the division were blown up and the whole line brought back to the Lys.[118] Over the next two days with considerable artillery and trench mortar support the Germans advanced slowly against the troops of the division until the line consisted of small groups of isolated men, who in some cases had been fighting for 30 hours.[119]

I think the only thing that saved us that night was the amount of liquor the Bosches found in Estaires and Neuf-Berquin, as I have never heard such a noise in my life as they made, singing.

— An officer of the 5th Durham Light Infantry[120]

Looting also slowed the Germans after they captured Merville in front of the 150th Brigade, where the 4th East Yorkshire were reduced to three officers and 120 men.[121] By 12 April the division's line was reduced to a thin and disorganised one north and north-west of Merville; it was in no state to withstand a determined attack, with only the 149th Brigade able to mount resistance to the slow German advance that day. During the night and next morning, the division was relieved by the 5th Division and withdrawn to the reserve line. Use of composite battalions drawn from the division's support units had reduced the strength of the division (excluding artillery) to 55 officers and 1100 men.[122]

Battle of the Aisne

Both Corps and Army Commanders (General Sir H S Horne) praised the division in its slowing of the Germans on the Lys, giving time for reserves to be brought in.[123] The division once again started to rebuild its strength with new recruits, and was in the Roquetoire area training, when on 23 April it received orders to move to the Aisne Area, considered a quiet part of the line, to replace French Divisions now around Amiens. The 50th Division, together with the 8th, 21st, 25th and later the 19th Divisions formed IX Corps under command of the French Sixth Army.[124]

Arriving on 27–28 April, the division went into the line on 5 May between Pontavert and Chaudardes on the Chemin des Dames ridge with all three brigades on a front of 7,700 yards, with the river Aisne behind them.[125] On the orders of General Duchêne they were concentrated in the front line with little defence in depth.[126] The division took advantage of this 'quiet front' to rest and train the new recruits that filled the ranks. Patrolling was carried out into no-man's land, and a trench raid was carried out on 25 May that captured a prisoner. More experience troops had earlier noticed the signs of an impending attack,[127] which was confirmed to the division on 26 May.[128]

When the attack came at 1 a.m. on 27 May, 3,719 German guns were used on a 24-mile front, firing gas and high explosive.[129] The British and French artillery had also been silenced, and communication between the front line and headquarters severed. The attack by 28 divisions of German infantry overwhelmed the front line, the trenches of which had been levelled in some areas. The concentration in the front line aided the infiltration tactics of the storm-troopers, meant almost the entire 150th Brigade was overrun and captured. Later in the day the remains of the 5th Durham Light Infantry and the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers, the reserve battalions of their Brigades, and other stragglers, some infantry, pioneers and engineers, were formed into the 149th/151st Brigade at Chaudardes. Few in the front line battalions escaped. The division's artillery brigades lost all of their guns and most of the men were captured when surrounded early in the day. Even the Division H.Q. at Beaurieux, was forced to move and had men captured from it. By the evening the division had lost 5,106 officers and men, killed wounded and missing (mostly captured).[130] The remnants of the division became more intermingled with other divisions as it was pushed back, with a battalion formed from stragglers under Lt. Colonel Stead joining the 74th Brigade on 30 May. The rest of the division was withdrawn on 31 May to Vert la Gravelle, where it could muster only around 700 infantrymen.[131]

Stragglers continued to arrive, and on 4 June a force of three weak battalions, known as General Marshall's Composite Force, consisting of the 149th, 150th, and 151st battalions totalling around 1400 men, was sent to the 19th Division, and on 7 June helped stop a German attack on the Bois d'Eglise. Reinforced by Lt. Colonel Stead's battalion on 8 June, this composite force rejoined the division on 19 June.[132]

Reconstitution

While preparing to move back to the British zone at the end of June, the division received orders that its units were to be reduced to cadre, 10 officers and 51 other ranks for the infantry battalions, these cadres and the surplus personnel were to leave the division on arrival at Huppy on 5 July.[133]

The infantry brigades were reformed with six battalions from Salonika (many of whose men were suffering from malaria), one from Palestine and two that had been in France since August 1914.[134] The artillery Brigades were also reformed and the pioneers replaced.[135]

Hundred Days

After conducting training, those men being treated for malaria restricted to four hours a day,[133] the newly reassembled Division joined the Fourth Army as part of XIII Corps in October.[136] The division took part in the Battle of Beaurevior from 3 to 5 October, capturing the villages of Le Catelet and Gouy at the Northern end of the Riqueval tunnel of the St. Quentin Canal.[136] On 8 October the division fought at the Second Battle of Cambrai at Grouy.[137] The division went into action again on the Selle and by 25 October was at the western edge of the Forêt de Mormal.[137] The division's last battle began on 4 November, took the division through the Southern part of the Forêt de Mormal.[138] The division had been taken out of the line and was resting at Solre-le-Château when the Armistice came into effect.[139]

Post-war

After an inspection by the King on 1 December,[140] demobilization started and by 19 March 1919 the division had ceased to exist in France.[139]

It was reformed again in England on 1 April 1920 as the Northumbrian Division of the Territorial Army.[139]

Order of Battle, World War I

- Peacetime HQ: Richmond (Yorkshire)

149th (Northumberland) Brigade

Until July 1918:

- 1/4th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/5th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/6th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/7th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers – transferred to 42nd Division as a Pioneer Battalion, 10 February 1918

- 1/5th (Cumberland) Battalion, Border Regiment – joined May 1915, left for 151st Brigade December 1915

- 149th Machine Gun Company – formed 6 February 1916, moved to Divisional Machine Gun battalion 1 March 1918

- 149th Trench Mortar Battery – formed 18 June 1916

From July 1918:

- 3rd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers – joined 15 July 1918

- 13th (Scottish Horse) Battalion, Black Watch – joined 15 July 1918

- 2nd Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers – joined 15 July 1918

- 149th Trench Mortar Battery – reformed 15 July 1918

150th (York and Durham) Brigade

Until July 1918:

- 1/4th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/4th Battalion, Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own (Yorkshire Regiment) – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/5th Battalion, Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own (Yorkshire Regiment) – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/5th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – to 151st Brigade 12 February 1918

- 150th Machine Gun Company – formed 1 February 1916, moved to Divisional Machine Gun battalion 1 March 1918

- 150th Trench Mortar Battery – formed 18 June 1916

From July 1918:

- 2nd Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers – joined 16 July 1918

- 7th (Service) Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment – joined 15 July 1918

- 2nd Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers – joined 15 July 1918

- 150th Trench Mortar Battery – reformed 16 July 1918

151st (Durham Light Infantry) Brigade

Until July 1918

- 1/6th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/7th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – left to become Division's Pioneer Battalion 16 November 1915

- 1/8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 1/9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – left 12 February 1918

- 1/5th Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment – joined 11 June 1915, left 21 December 1915

- 1/5th (Cumberland) Battalion, Border Regiment – joined from 149th Brigade December 1915, left 12 February 1918

- 1/5th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – joined from 150th Brigade 12 February 1918, reduced to cadre and left 15 July 1918

- 151st Machine Gun Company – formed 6 February 1916, moved to Divisional Machine Gun battalion 1 March 1918

- 151st Trench Mortar Battery – formed 18 June 1916

From July 1918

- 6th (Service) Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers – joined 16 July 1918

- 1st Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry – joined 15 July 1918

- 4th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps – joined 16 July 1918

- 151st Trench Mortar Battery – reformed 16 July 1918

Artillery

- 1st Northumbrian Brigade – renamed 250th Brigade R.F.A. 16 April 1916:

- 1st, 2nd and 3rd Northumberland batteries – renamed A, B and C batteries 16 April 1916.[lower-alpha 7]

- D battery – formed 10 April 1916, transferred to 253rd Brigade on 16 April and replaced by 4th Durham (Howitzer) battery, renamed D battery[lower-alpha 8]

- 1st Northumbrian Ammunition Column. Peacetime HQ – Newcastle

- 2nd Northumbrian Brigade – renamed 251st Brigade R.F.A. 16 April 1916:

- 1st, 2nd and 3rd East Riding Batteries – renamed A, B and C Batteries 16 April 1916.[lower-alpha 7]

- D Battery – formed 10 April 1916, transferred to 253rd Brigade on 16 April and replaced by 5th Durham (Howitzer) Battery, renamed D Battery[lower-alpha 8]

- 2nd Northumbrian Ammunition Column. Peacetime HQ – Hull

- 3rd Northumbrian (County of Durham) Brigade – renamed 252nd Brigade R.F.A. 16 April 1916. Broken up in late January 1917,[143] D (Howitzer) battery distributed to 250th and 251st Brigades.:

- 1st, 2nd and 3rd Durham Batteries.[lower-alpha 9] – Renamed A, B and C Batteries 16 April 1916, B broken up on 16 November, then C renamed B.[lower-alpha 7] In January 1917 A battery transferred to 242nd Brigade R.F.A., B to 72nd Brigade.

- D Battery – formed 10 April 1916, transferred to 253rd Brigade on 16 April and replaced by D/61 Battery, renamed D Battery[lower-alpha 10]

- 3rd Northumbrian (County of Durham) Ammunition Column. Peacetime HQ – Seaham Harbour

- 4th Northumbrian (County of Durham) Howitzer Brigade – renamed 253rd Brigade R.F.A. 16 April 1916. Broken up 16 November and distributed to 250th and 251st brigades.:

- 4th Durham and 5th (Howitzer) batteries.[lower-alpha 11] – transferred to 250th and 251st brigades on 16 May 1916

- D/61 battery – joined from the Guards Division 21 February 1916, transferred to 252nd brigade on 16 May 1916

- A, B and C batteries – the D batteries from 250th, 251st and 252nd brigades joined on 16 May 1916 and renamed[lower-alpha 7]

- 4th Northumbran (County of Durham) Ammunition Column. Peacetime HQ – South Shields

- Northumbrian (North Riding) Heavy Battery R.G.A.[lower-alpha 12] – joined 13 Brigade R.G.A. on 16 May 1915 Peacetime HQ – Middlesbrough

- Trench Mortars

- V.50 Heavy Trench Mortar battery RFA.[lower-alpha 13] – joined July 1916, left for V/VIII Corps on 11 February 1918

- X.50, Y.50 and Z.50 Medium Mortar batteries RFA.[lower-alpha 14] – formed 5 March 1916, Z broken up on 1 March 1918 and distributed to X and Y batteries

Pioneers

- 1/7th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – joined from 151st Brigade 16 November 1915, left 20 June 1918 for 8th Division

- 5th (Service) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment – joined 14 July 1918

Machine gunners

- 245th Machine Gun Company – joined 30 July 1917, moved to Divisional Machine Gun battalion 1 March 1918

- 50th Battalion MGC – formed 1 March 1918 from Brigade and Division machine gun companies

Mounted Troops

- RHQ and 'A' Squadron, 1/1st Yorkshire Hussars from the Yorkshire Mounted Brigade – left 10 May 1916

- Northumbrian Divisional Cyclist Company – left 20 May 1916

Engineers

Originally composed of companies forming the 1st Newcastle Engineers, the 1st and 2nd (Newcastle) Northumbrian Field Companies and the Northumbrian Division Signal Company. Peacetime HQ at Newcastle.

- 1st (Newcastle) Northumbrian Field Company – left December 1914, rejoined June 1915. Renamed the 446th (1st Northumbrian) Field Company in 1917

- 2nd (Newcastle) Northumbrian Field Company – Renamed the 447th (2nd Northumbrian) Field Company in 1917

- 7th Field Company – joined June 1915

- Northumbrian Division Signal Company – Renamed the 50th Divisional Signals Company in May 1915

Transport & Supply

The Northumbrian Divisional Transport and Supply Column was renamed the 50th Divisional Train (Army Service Corps) in May 1915, and was composed of:

- Divisional Company (HQ)

- Northumbrian Brigade Company

- York and Durham Brigade Company

- Durham Light Infantry Brigade Company

Renamed the 467–470 Companies A.S.C. in May 1915.[lower-alpha 15]

Medical

- 1st Northumbrian Field Ambulance. Peacetime HQ – Newcastle

- 2nd Northumbrian Field Ambulance. Peacetime HQ – Darlington

- 3rd Northumbrian Field Ambulance. Peacetime HQ – Hull

Battle honours

From[144]

- Second Battle of Ypres

- St. Julien

- Frizenberg Ridge

- Bellewaarde Ridge

- Battle of the Somme (1916)

- Battle of Arras (1917)

- First Battle of the Scarpe

- Second Battle of the Scarpe

- Third Battle of the Scarpe

- Third Battle of Ypres

- Battle of the Somme (1918)

- St Quentin

- Rosières

- Battle of the Lys (1918)

- Estaires

- Hazebrouck

- Third Battle of the Aisne

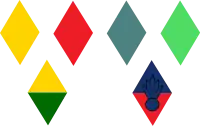

Battle Insignia

The practice of wearing battalion specific insignia (often called battle patches) in the B.E.F. began in mid 1915 with the arrival of units of Kitchener's Armies and was widespread after the Somme Battles of 1916.[145] The patches were devised to a divisional scheme and were worn in 1917,[146] all were worn at the top of both sleeves.[147]

| Top (left to right) 1/4th, 1/5th, 1/6th, 1/7th Northumberland Fusiliers. Lower (left to right) 149th machine gun company, 149th trench mortar battery.[147] |

| Top (left to right) 1/4th East Yorkshires, 1/4th, 1/5th Green Howards, 1/5th Durham Light Infantry. Lower (left to right) 150th machine gun company, 150th trench mortar battery.[147] |

| Top (left to right) 1/5th, Borderers, 1/6th, 1/8th, 1/9th Durham Light Infantry. Lower (left to right) 151st machine gun company, 151st trench mortar battery.[147] |

Commanders

General Officers Commanding have included:[148][149]

| Appointed | General officer commanding |

|---|---|

| April 1908 | Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Baden-Powell |

| March 1910 | Major-General Francis Plowden |

| September 1911 | Major-General Frederick Hammersley |

| 1 March 1912 | Major-General Benjamin Burton |

| 9 April 1915 | Major-General Sir Walter Lindsay |

| 29 June 1915 | Major-General the Earl of Cavan |

| 5 August 1915 | Major-General Percival Wilkinson |

| 25 February 1918 | Brigadier-General Clifford Coffin (temporary) |

| 17 March 1918 | Brigadier-General A. U. Stockley (acting) |

| 23 March 1918 | Major-General Henry Jackson |

| July 1919 | Major-General Sir Percival Wilkinson |

| July 1923 | Major-General Frederick Dudgeon |

| July 1927 | Lieutenant-General Sir George Cory |

| April 1928 | Major-General Henry Newcome |

| February 1931 | Major-General Richard Pope-Hennessy |

See also

- 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division – Second World War formation

- 63rd (2nd Northumbrian) Division – 2nd Line duplicate in the First World War

- List of British divisions in World War I

Notes

- Reported as "a Yorkshire division" in The Times of 29 October 1907

- An example of the dispersion was the 1/4th East Yorkshires, they had A Company with the 11th Hussars, B Company with the Queen's Bays, C Company in reserve and D Company with the 5th Dragoon Guards.[24]

- 5th Borderers: A Company to 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, B to 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment, C to 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and D to 7th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. 5th Northumberland Fisiliers: A Company to 5th South Lancashire Regiment, B to 1st King's Own, C to 2nd Essex Regiment and D to 2nd Royal Irish Regiment.

- Only firing for 10 minutes as ammunition was in short supply.[35]

- It would be used as the "nursery" sector for some newly arrived Service Divisions.

- To their right, the creeping barrage of the Australians began 70 yards behind their trenches and disrupted their advance from the start, leaving the 8th with an open flank.[74]

- 4 18 Pounders each, 6 after November 1916

- 4 4.5" howitzers after the transfer, 6 after January 1917

- Peacetime HQs – Seaham Harbour, Durham and West Hartlepool

- 4 4.5" howitzers after the transfer

- Peacetime HQs – South Shields and Hebburn on Tyne

- 4 4.7" Guns

- 4 9.45-inch Heavy Mortars

- 4 then 6 6" Mortars

- Peacetime HQs: Gateshead, Newcastle, Hull and Sunderland

References

- Chappel pp. 24, 42

- Westlake 1992, p. 3

- Conrad, Mark (1996). "The British Army, 1914". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Westlake, Ray (2011). The Territorials, 1908–1914: A Guide for Military and Family Historians. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1848843608.

- Wyrall p. 4

- Ward p. 321

- Wyrall p. 5

- Wyrall p. 6

- Wyrall p. 15

- Wyrall pp. 17-20

- Wyrall pp. 20-21

- Wyrall pp. 24–27

- Wyrall pp. 29—33

- Wyrall pp. 33-34

- Wyrall pp. 34-35

- Wyrall p. 36

- Wyrall pp. 36—38

- Wyrall p. 48 footnote

- Wyrall pp. 48-57

- Wyrall pp. 54, 362-363

- Wyrall p. 74

- Wyrall p. 57

- Wyrall p. 60

- Wyrall p. 58

- Wyrall pp. 65–66

- Wyrall pp. 67–68

- Wyrall pp. 61-62

- Wyrall pp. 63-64

- Wyrall p. 71

- Wyrall pp. 75-76

- Wyrall pp. 72, 79, 81

- Wyrall pp. 75, 78

- Wyrall p. 83

- Wyrall p. 85

- Wyrall pp. 83-86

- Wyrall p. 86

- Wyrall pp. 86-88

- Wyrall p. 89

- Wyrall p. 92

- Wyrall pp. 93-94

- Wyrall pp. 92-93

- Wyrall p. 100

- Wyrall p. 101

- Wyrall p. 103

- Wyrall p. 104

- Wyrall p. 107

- Wyrall p. 108

- Wyrall pp. 100, 109

- Wyrall pp. 117-118

- Wyrall pp. 118-119

- Wyrall pp. 123-124

- Wyrall p. 125

- Wyrall p. 128

- Wyrall pp. 129–133

- Wyrall p. 134

- Wyrall pp. 136-137

- Wyrall pp. 138-141

- Wyrall p. 141

- Wyrall p. 144

- Wyrall pp. 149-153

- Wyrall pp. 153-159

- Wyrall p. 161

- Wyrall p. 162

- Wyrall p. 163

- Wyrall p. 164

- Wyrall pp. 167-168

- Wyrall p. 168

- Wyrall pp. 169-170

- Wyrall pp. 172-173

- Wyrall p.173

- Wyrall p. 174

- Wyrall pp. 174–175

- Wyrall p. 177

- Wyrall pp. 176-181

- Wyrall pp. 183-191

- Wyrall p. 189

- Wyrall pp. 192-195

- Wyrall pp. 195-197

- Wyrall p. 201

- Wyrall p. 198

- Wyrall pp. 198-201

- Wyrall p. 205

- Wyrall pp. 209-214

- Wyrall pp. 215-216

- Wyrall pp. 217-221

- Wyrall pp. 222-223

- Wyrall pp. 227-228

- Wyrall p. 2228

- Wyrall pp. 229-230

- Wyrall p. 230

- Wyrall pp. 231–237

- Wyrall p. 237

- Wyrall p. 239

- Wyrall pp. 242-247

- Wyrall pp. 252-253

- Hart pp. 28-29

- Wyrall p. 254

- Wyrall p. 255

- Wyrall p. 256

- Hart pp. 39-43, 48

- Wyrall p. 257

- Wyrall pp. 255-256

- Wyrall p. 262-265

- Wyrall pp. 266-274

- Wyrall pp. 276-277

- Wyrall pp. 278-287

- Wyrall pp. 281-282

- Wyrall pp. 293-298

- Wyrall pp. 300–303

- Wyrall pp. 304–305

- Wyrall pp. 306-307

- Wyrall p. 305 footnote

- Wyrall p. 308

- Wyrall pp. 308-309

- Wyrall p. 309

- Wyrall pp. 310-317

- Wyrall pp. 315-319

- Wyrall pp. 320–329

- Wyrall p. 329

- Wyrall pp. 332-333

- Wyrall pp. 332-334

- Wyrall.p 334

- Wyrall p. 335

- Wyrall pp. 335-336

- Hart p. 268

- Hart p. 269

- Wyrall p. 336

- Hart 272

- Wyrall pp. 338-347

- Wyrall pp. 348-349

- Wyrall pp. 350-351

- Wyrall p. 352

- Becke 1936, p. 98

- Wyrall pp. 352, 367

- Wyrall p. 354

- Wyrall p. 355

- Wyrall p. 356

- Baker, Chris. "The 50th (Northumbrian) Division". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Wyrall p. 354 (facing)

- Wyrall pp. 358–360.

- Wyrall pp. 362–367

- Wyrall p. 201 footnote

- Wyrall p. 367

- Chappel pp 5-6

- Hibbard p. 4

- Hibbard pp. 51-52

- "Army Commands" (PDF). Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Becke p.93

Bibliography

- Becke, Major A.F. (1936). Order of Battle of Divisions Part 2A. The Territorial Force Mounted Divisions and the 1st-Line Territorial Force Divisions (42–56). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 1-871167-12-4.

- Chappel, M (1986). British Battle Insignia (1). 1914-18. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9780850457278.

- Hart, P (2009). 1918. A Very British Victory. London: Orion Books Ltd. ISBN 9780753826898.

- Hibbard, Mike; Gibbs, Gary (2016). Infantry Divisions, Identification Schemes 1917 (1 ed.). Wokingham: The Military History Society.

- Ward, S G P (1962). Faithful. The Story of the Durham Light Infantry. Naval and Military Press. ISBN 9781845741471.

- Westlake, Ray (1992). British Territorial Units 1914–18. Men-at-Arms Series. Vol. 245. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-168-7.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1939]. The History of the 50th Division, 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: P. Lund, Humphries. ISBN 1-84342-206-9. OCLC 613336235. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

External links

- The British Army in the Great War: The 50th (Northumbrian) Division

- The Story of the 6th Battalion, The Durham Light Infantry France, April 1915-November 1918 at Project Gutenberg

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081014125847/http://www.4thbnnf.com/03_organisation.html