12th (Eastern) Infantry Division

The 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army, which fought briefly in the Battle of France during the Second World War. In March 1939, after the re-emergence of Germany as a European power and its occupation of Czechoslovakia, the British Army increased the number of divisions within the Territorial Army by duplicating existing units. The 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was formed in October 1939, as a second-line duplicate of the 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division.

| 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

The shoulder insignia of the division | |

| Active | 7 October 1939 – 11 July 1940 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Second World War * Battle of France |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Roderic Petre |

It was intended that the division would remain in the United Kingdom to complete training and preparation, before being deployed to France within twelve months of the war breaking out. The division was dispersed to defend Kent and guard strategically important and vulnerable locations. In France, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was suffering from a manpower shortage among rear-line units. To boost morale, provide additional labour for the rear echelon of the BEF, and acquire political capital with the French Government and military, the division was sent to France in April 1940, leaving behind most of its administration and logistical units as well as its heavy weapons and artillery. The men were assigned to aid in the construction of airfields and pillboxes. General Sir Edmund Ironside, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), secured a promise from the commander of the BEF, General Lord Gort, that the division would not be used in action owing to it being untrained and incomplete.

When Germany invaded the Netherlands and advanced into northern Belgium, the BEF and French armies moved to meet the attack, leaving the 12th Division behind. The main German attack came through the Ardennes, in southern Belgium beyond the main Allied armies, and then rapidly advanced into France. This move intended to cut off the British and French forces in northern France and Belgium, from other formations along the Franco-German border as well as the Allied supply centres. With no other reserves available, the 12th Division was ordered to the front line to defend several towns blocking the way between the main German assault and the English Channel. This resulted in the division being widely spread out. A brief skirmish occurred on 18 May, in which one of the division's battalions repulsed the German vanguard. However, on 20 May, three German panzer divisions attacked the division in several isolated actions. Without the means to stop the attacking Germans, the division was overwhelmed and destroyed. The survivors were evacuated to England, and the division was broken-up. Its assets were transferred to other formations to help bring them up to strength.

Background

During the 1930s, tensions increased between Germany and the United Kingdom and its allies.[1] In late 1937, German policy towards Czechoslovakia became hostile. During 1938, Germany demanded the annexation of the Sudetenland, the border areas of Czechoslovakia that were primarily inhabited by German-ethnic people. These demands led to an international crisis. To avoid war, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met with German chancellor Adolf Hitler in September and brokered the Munich Agreement. The agreement averted a war and allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland.[2] Although Chamberlain had intended for the agreement to further a peaceful resolution of issues, relations between the two countries soon deteriorated.[3] On 15 March 1939, Germany breached the terms of the agreement by invading and occupying the remnants of the Czech state.[4]

On 29 March, British secretary of state for war Leslie Hore-Belisha announced plans to increase the Territorial Army (TA) from 130,000 to 340,000 men and double the number of TA divisions.[5][lower-alpha 1] The plan was for existing TA divisions, referred to as the first-line, to recruit over their establishments (aided by improved pay and conditions) and then form a new division, known as the second-line, from cadres around which the new divisions could be expanded.[5][10] This process was dubbed "duplicating". The 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division provided cadres to create a second line "duplicate" formation, which became the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division.[11] Despite the intention for the army to grow, a lack of central guidance on the expansion and duplication process and a dearth of facilities, equipment and instructors complicated the programme.[5][12] In April 1939, limited conscription was introduced. At that time 34,500 men, all aged 20, were conscripted into the regular army, initially to be trained for six months before being deployed to the forming second line units.[11][13] The War Office had envisioned that the duplicating process and recruiting of the required number of men would take no more than six months.[12][14] The process varied widely between the TA divisions. Some were ready in weeks while others had made little progress by the time the Second World War began on 1 September.[12][14]

History

Formation

On 7 October, the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division became active. The division took control of the 35th, the 36th, and the 37th Brigades, as well as divisional support units, which the 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division had administered previously.[15] Because of the lack of official guidance, the newly constituted formations were at liberty to choose numbers, styles, and titles. The division adopted the number of their First World War counterpart: the 12th (Eastern) Division.[12] The division did not use their predecessor's divisional insignia, adopting a plain white diamond instead, which was painted on the division's vehicles but not worn on uniforms.[16]

The 35th Brigade consisted of the 2/5th, the 2/6th, and the 2/7th Battalions, Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey). The 36th Brigade comprised the 2/6th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment (2/6th Surrey), and the 6th and the 7th Battalions, Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment (6th RWK and 7th RWK). The 37th Brigade had the 5th Battalion, Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) (5th Buffs), and the 6th and the 7th Battalions, Royal Sussex Regiment (6th and 7th Sussex). On 25 October, the 2/6th East Surrey Regiment and the 5th Buffs were exchanged between the 36th and the 37th Brigades.[17][lower-alpha 2] The division was assigned to Eastern Command, and Major-General Roderic Petre became the General Officer Commanding.[15] Petre's prior experience included commanding the Sudan Defence Force during the inter-war period before being made commandant of the Senior Officers' School in 1938.[19]

Initial service and transfer to France

_in_France_1939-1940_F4573.jpg.webp)

The war deployment plan for the TA envisioned its divisions being sent overseas, as equipment became available, to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that had already been dispatched to Europe. The TA would join regular army divisions in waves as its divisions completed their training, the final divisions deploying one year after the war had begun.[20] In October 1939, Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, General Walter Kirke, was tasked with drawing up a plan, code named "Julius Caesar", to defend the United Kingdom from a potential German invasion.[lower-alpha 3] As part of this plan, the division was assigned to defend northern Kent.[22] In addition, its forces were dispersed to guard strategically important locations known to be vulnerable points.[23][24]

In early 1940, the division became caught up in an effort to address manpower shortages among the BEF's rear-echelon units.[lower-alpha 4] More men were needed to work along the line of communication, and the army had estimated that by mid-1940 it would need at least 60,000 pioneers for engineering and construction tasks.[26] The lack of such men had taxed the Royal Engineers (RE) and the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps (AMPC), and had also impacted frontline units that had to divert men from training to help construct defensive positions along the Franco-Belgian border.[27][28] To address this issue, it was decided to deploy untrained territorial units as an unskilled workforce, thereby alleviating the strain on the existing pioneer units and freeing up regular units to complete their training.[29][30] As a result, the decision was made to deploy the 12th (Eastern), 23rd (Northumbrian), and the 46th Infantry Divisions to France. Each division would leave their heavy equipment and most of their logistical, administrative, and support units behind. In total, the elements of the three divisions that were transported to France amounted to 18,347 men.[31][lower-alpha 5] The divisions were to aid in the construction of airfields and pillboxes. The intent was that by August their job would be completed and they could return to the United Kingdom to resume training before being redeployed to France as front-line soldiers.[33] The Army believed that this diversion from guard duty would also raise morale.[28] Lionel Ellis, the author of the British official history of the BEF in France, wrote that while the divisions "were neither fully trained nor equipped for fighting ... a balanced programme of training was carried out so far as time permitted".[34] Historian Tim Lynch commented the deployment also had a political dimension, allowing "British politicians to tell their French counterparts that Britain had supplied three more infantry divisions towards the promised nineteen by the end of the year".[30]

General Edmund Ironside, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, opposed this use of these divisions. He reluctantly caved to the political pressure to release the divisions, having been assured by General Sir John Gort (commander of the BEF) that the troops would not be used as frontline combat formations.[35] The 12th left the United Kingdom on 20 April 1940, arrived in France two days later, and was placed under the direct command of the BEF.[15]

German invasion of France

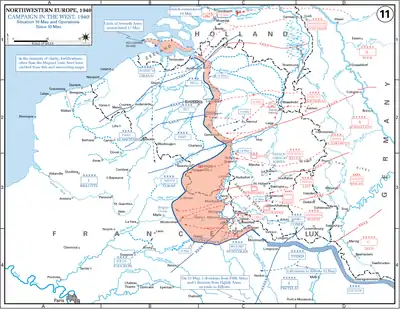

On 10 May 1940, the Phoney War—the period of inactivity on the Western Front since the start of the conflict—ended as the German military invaded Belgium and the Netherlands.[36] As a result, the majority of the BEF along with the best French armies and their strategic reserve moved forward to assist the Belgian and Dutch armies.[37] While these forces attempted to stem the tide of the German advance, the main German assault pushed through the Ardennes Forest and crossed the River Meuse. This initiated the Battle of Sedan and threatened to split the Allied armies in two, separating those in Belgium from the rest of the French military along the Franco-German border.[38]

Once the Allied commanders realised that the German crossing of the Meuse had turned into a breakthrough, the BEF and French armies began a fighting withdrawal from Belgium back to France. On 17 May, the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was ordered to assemble around Amiens. The next day, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Bridgeman, in charge of the BEF's rear headquarters, requested that Petre take command of an ad hoc force that included his 36th Brigade, a makeshift garrison in Arras and the 23rd (Northumbrian) Division. This collection of troops was dubbed Petreforce. Petreforce, along with the 12th Division, were the only troops blocking the German route to the sea and the defeat of the BEF.[39][40] On being appointed to this command, Petre was provided with an over-optimistic report that he then passed on to his subordinates: the French were resilient on either side of the German breakthrough, and that only small German units had penetrated deep into French territory. With this information, it was expected that Petreforce could handle the German incursion.[41] However, the 12th Division was woefully under-equipped for the task assigned to it. On average, there were only four Boys anti-tank rifles and one ML 3-inch mortar per each of the divisions nine battalions. In comparison, a fully equipped division was to have 361 anti-tank rifles and 18 three-inch mortars spread over these units. Some units were issued with training rounds for the anti-tank rifles, which were not effective against tanks. Within the 35th Brigade, there was only five such rifles and a total of 35 rounds. At the platoon level, there was an average of one Bren light machine gun instead of three.[42]

Demise of the division

The 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was widely dispersed across four areas, unable to support each other, and this further eroded the division's limited fighting power. The 35th Brigade took up positions along the eastern side of Abbeville. The 36th Brigade dispatched the 6th RWK and the 5th Buffs to Doullens. The 7th RWK, supplemented by four field guns obtained from a Royal Artillery training school, occupied Cléry-sur-Somme to block the exits from Péronne, which had a bridge across the Canal du Nord. French troops were supposed to hold it, but they never arrived. The 37th Brigade was caught-up in a German bombing raid on Amiens, which resulted in between 60 and 100 casualties.[43][44][45] It then dispatched the 6th Sussex and the 7th Sussex to take up positions south of the town. The 2/6th Surrey's were ordered to move south to join the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, but ended up being allocated to an ad hoc composition called Beauforce.[43]

The German 1st Panzer Division reached Péronne during the evening of 18 May. They crossed the canal and attempted to carry on their advance, but the 7th RWK and their four field guns stopped them. Fighting continued until dark, when the Germans fell back into Péronne and the 7th RWK fell back to Albert.[46] The next day saw no German activity along the division's front. On 20 May, the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was engaged in a series of isolated battles. The 1st Panzer Division advanced on Albert and overran the 7th RWK. It then moved towards Amiens and destroyed the 37th Brigade's 7th Sussex in the process. The 6th Panzer Division reached Doullens and was held up by the 36th Brigade for two and a half hours, before they overwhelmed the brigade. The 2nd Panzer Division arrived at Abbeville and occupied the town after defeating the 35th Brigade.[47] Ellis wrote that the 12th Division "had practically ceased to exist", as a result of the fighting that saw the "whole tract of country between the Scarpe and the Somme" fall into German hands, and left the way to the English Channel open.[48]

The German XXXXI Panzer Corps war diary reported that the 6th Panzer Division was "only able to gain ground slowly and with continual fighting against an enemy who defended himself stubbornly".[48] Historians have praised the division for delaying the German advance for several hours, despite being under-equipped, un-prepared and fighting against unfavourable odds.[49] The historian Gregory Blaxland was more critical, and wrote "it was both tragic and wasteful to have committed these men of little training but great spirit to battle at such hopeless disadvantage."[50] Both Blaxland and the historian Julian Thompson cited the praise delivered upon these battalions by the Germans, in their war diaries. However, they argued that the British Army had not heeded the lessons of the invasion of Poland nor given enough thought into how infantry should counter tanks. They believe had the battalions been concentrated and placed in more defensible positions, such as behind the Canal du Nord, they would have held greater tactical value and delayed the Germans longer than they achieved. The BEF had intended to deploy the 12th Division behind this canal, but this intention was not acted upon prior to the division being dispersed.[51][52] Blaxland highlighted that the overall lack of training within the territorial soldiers should not have been an issue, as all levels of command were held by regular soldiers who should have been able to impress their greater experience upon the recruits.[50] Thompson noted, however, "it has to be borne in mind that a delay of even one hour was of huge benefit" to the BEF.[52]

Most of Petreforce suffered a similar fate. The 23rd (Northumbrian) Division was overrun by the 8th Panzer Division on 20 May.[53][54] Meanwhile, the 5th Infantry Division and the 50th (Northumbrian) Motor Division had taken up positions in Arras, and the 5th Division took command of the garrison. On 25 May, Petreforce was officially abolished.[55] The remnants of the 12th Division were evacuated back to England. The 36th Brigade evacuated via Dunkirk, and the rest of the division was largely evacuated via Cherbourg during Operation Aerial.[56] Divisional casualty information is sparse. The 35th Brigade started the campaign with 2,400 men, and was reduced to 1,234 after their encounter with the 2nd Panzer Division.[57] Within the 36th Infantry Brigade, the 6th RWK was reduced from 578 men to 75, and the 605 strong 5th Buffs was reduced to 80.[58]

Disbandment

As soon as the Allied troops returned from France, the British Army began implementing lessons learnt from the campaign. This involved the decision to abandon the two-brigade motor division concept and for the basic infantry division to be based around three brigades.[59][60][lower-alpha 6] This entailed the break up of four second-line TA divisions to reinforce depleted formations and aid in transforming the Army's five motor divisions into infantry divisions.[59][60][lower-alpha 7] Consequently, the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division was disbanded on 11 July, and its units dispersed.[15]

The 35th Infantry Brigade (along with the 113th Field Regiment and the 67th Anti-Tank Regiment) were transferred to the 1st London Division, a motor formation. The arrival of the brigade was part of the division's re-organisation into an infantry division. With little change to the composition of the brigade, it would fight in the Italian Campaign between 1943 and 1945.[67] The 36th Infantry Brigade was briefly attached to the 2nd London Division (another motor formation), before becoming an independent infantry brigade directly under the command of either the War Office or as a corps-level asset. It was eventually transferred to the 78th Infantry Division, and the brigade (with some changes) fought in the North African Campaign in 1942, the invasion of Sicily in 1943, and in the Italian Campaign from 1943 through to the end of the war.[68] The 37th Infantry Brigade became an independent formation under corps level command. It was re-designated the 7th Infantry Brigade in 1941, before being assigned to a variety of divisions based in the United Kingdom throughout the rest of the war.[69] The 114th Field Regiment also joined the 2nd London Division and stayed with the division until the end of 1941.[70] It was then transferred to India and attached to the 20th Indian Infantry Division and fought in the Burma Campaign.[71] The 118th Field Regiment was transferred to the 18th Infantry Division, to bring it up to strength in artillery. They would fight and surrender following the Battle of Singapore in 1942.[72] The division's engineers became the XII Corps Troops, Royal Engineers, and served as part of the Second Army in the North-West Europe campaign in 1944–1945.[73] The survivors of the divisional signals unit were allocated to signal units based within the United Kingdom, Sudan, and units in the Mediterranean and Middle East theatre.[74]

Order of battle

12th (Eastern) Infantry Division (1939–40):[15]

35th Infantry Brigade[75]

- 2/5th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey)

- 2/6th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey)

- 2/7th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey)

36th Infantry Brigade[76]

- 2/6th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment (left 25 October 1939)

- 6th Battalion, Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment

- 7th Battalion, Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment

- 5th Battalion, Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) (from 25 October 1939)

37th Infantry Brigade[69]

- 5th Battalion, Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) (left 25 October 1939)

- 6th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment

- 7th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment

- 2/6th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment (from 25 October 1939)

Divisional Troops[15]

- 12th (Eastern) Divisional artillery, Royal Artillery

- 113th (Home Counties) Field Regiment

- 114th (Sussex) Field Regiment

- 118th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 67th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 12th (Eastern) Divisional Engineers, Royal Engineers

- 262nd Field Company

- 263rd Field Company

- 264th Field Company

- 265th (Sussex) Field Park Company

- 12th (Eastern) Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals

Footnotes

- The Territorial Army (TA) was a reserve of the British regular army made up of part-time volunteers. By 1939, its intended role was the sole method of expanding the size of the British Army. (This is comparable to the creation of Kitchener's Army during the First World War.) Existing territorial formations would create a second division using a cadre of trained personnel and, if needed, a third division would be created. All TA recruits were required to take the general service obligation: if the British Government decided, territorial soldiers could be deployed overseas for combat. (This avoided the complications of the First World War-era Territorial Force, whose members were not required to leave Britain unless they volunteered for overseas service.)[6][7][8][9]

- British battalion numbering nomenclature used fractions to signify when a battalion had created a second line unit. The number prior to the fraction detailed the 'line', and the number after was the parent battalion. For example, if the 1st Battalion formed a second line unit, it would be called the 2/1st etc.[18]

- "Julius" was the code word to bring troops to a state of readiness within eight hours. The code word "Caesar" meant an invasion was imminent, and units were to be readied for immediate action. Kirke's plan assumed the Germans would use 4,000 paratroopers, followed by 15,000 troops landed via civilian aircraft once airfields had been secured (Germany only actually had 6,000 such troops), and at least one division of 15,000 troops to be used in an amphibious assault.[21]

- By the end of April, 78,864 men were employed on lines-of-communication duties; 23,545 were allocated to headquarters, hospitals, and other rear-echelon duties; 9,051 were allocated as drafts; 2,515 had not been assigned a role; and 6,859 were supporting the Advanced Air Striking Force. Around 10,000 men who were assigned to railway and other construction tasks to support the lines of communication were included in these figures.[25]

- For comparison, the 1939 war-establishment (the on-paper strength) of a three-brigade infantry division was 13,863 men.[32]

- British military doctrine development during the inter-war period established three types of divisions: the infantry division, the mobile division (later called an armoured division), and the motor division (a motorised infantry division). The primary role of the infantry division was to penetrate the enemy's defensive line with the support of infantry tanks. Any gap created would then be exploited by mobile divisions, and the territory thus captured would be secured by the fast-moving motor divisions. These tactics would transform the attack into a break-through, while maintaining mobility.[61] By 1940, five such divisions had been formed within the TA: the 1st London, the 2nd London, the 50th (Northumbrian), the 55th (West Lancashire), and the 59th (Staffordshire) Motor Divisions.[62][63] French wrote that the motor division "matched that of the German army's motorized and light divisions. But there the similarities ended." German motorised divisions contained three regiments (comparable to British brigades) and were as fully equipped as a regular infantry division, while the smaller light divisions contained a tank battalion. The motor division, fully motorised and capable of transporting all their infantry, contained no tanks and was "otherwise much weaker than normal infantry divisions" or their German counterparts.[62]

- The two-brigade strong 23rd (Northumbrian) Division was disbanded on 23 June. One brigade was transferred to the 50th (Northumberland) Motor Division as part of their transition into an infantry formation, while the other was eventually transferred to the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division to bring it up to full strength.[64] The 66th Infantry Division was disbanded on 3 June, with one brigade transferred to the 59th (Staffordshire) Motor Division to finalise its re-organisation, and the other was initially attached to another transiting motor formation, the 1st London Division.[65] On 7 August, the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, destroyed in France, was re-created by the re-designation of its second-line duplicate, the 9th (Highland) Infantry Division.[66]

Citations

- Bell 1997, pp. 3–4.

- Bell 1997, pp. 258–275.

- Bell 1997, pp. 277–278.

- Bell 1997, p. 281.

- Gibbs 1976, p. 518.

- Allport 2015, p. 323.

- French 2001, p. 53.

- Perry 1988, pp. 41–42.

- Simkins 2007, pp. 43–46.

- Messenger 1994, p. 47.

- Messenger 1994, p. 49.

- Perry 1988, p. 48.

- French 2001, p. 64.

- Levy 2006, p. 66.

- Joslen 2003, p. 56.

- Chappell 1987, p. 21.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 56, 282, 284, 286.

- Story 1961, p. 9.

- "No. 34171". The London Gazette. 18 June 1935. p. 3928., "No. 34419". The London Gazette. 20 July 1937. p. 4668., "No. 34511". The London Gazette. 17 May 1938. p. 3196.

- Gibbs 1976, pp. 455, 507, 514–515.

- Newbold 1988, p. 40.

- Newbold 1988, p. 47.

- Chaplin 1954, p. 116.

- Martineau 1955, p. 219.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 19 and 21.

- Perry 1988, p. 52.

- Rhodes-Wood 1960, pp. 29, 228.

- Jones 2016, p. 228.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 19, 21.

- Lynch 2010, p. 52.

- Ellis 1954, p. 19; Lynch 2010, p. 52; Joslen 2003, pp. 56, 62, and 75.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 131 and 133.

- Collier 1961, p. 83.

- Ellis 1954, p. 21.

- Lynch 2010, p. 52; Smalley 2015, p. 75; Murland 2016, Chapter Four: "Massacre of the Innocents 19–20 May 1940".

- Weinberg 1994, p. 122.

- Weinberg 1994, pp. 123–125.

- Weinberg 1994, pp. 126–127.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 59, 65, 77.

- Sebag-Montefiore 2006, pp. 129–131.

- Sebag-Montefiore 2006, p. 131.

- Joslen 2003, p. 131; French 2001, pp. 38–39; Thompson 2009, p. 69; Lynch 2010, p. 98.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 77–79.

- Sebag-Montefiore 2006, p. 138.

- Thompson 2009, p. 73.

- Ellis 1954, p. 78.

- Ellis 1954, p. 80.

- Ellis 1954, p. 81.

- Ellis 1954, p. 81; Fraser 1999, p. 61; Horne 2007, p. 561; Lynch 2010, p. 52.

- Blaxland 1973, p. 130.

- Blaxland 1973, pp. 117, 130.

- Thompson 2009, p. 77.

- Thompson 2009, pp. 81–82.

- Rissik 2004, pp. 37–42.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 131, 139.

- Martineau 1955, p. 233; Haswell 1967, p. 129; Langley 1972, p. 104; Sebag-Montefiore 2006, pp. 137–138.

- Lynch 2010, p. 121.

- Sebag-Montefiore 2006, pp. 137–138.

- French 2001, pp. 189–191.

- Perry 1988, p. 54.

- French 2001, pp. 37–41.

- French 2001, p. 41.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 37, 41, 61, 90, 93.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 79–82, 301.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 93–94, 97, 362.

- Joslen 2003, p. 55.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 37, 56, 282.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 41–42, 101, 284.

- Joslen 2003, p. 286.

- Joslen 2003, p. 41.

- Joslen 2003, p. 505.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 60–61.

- Morling 1972, pp. 211, 225–234.

- Lord & Watson 2003, p. 153.

- Joslen 2003, p. 282.

- Joslen 2003, p. 284.

References

- Allport, Alan (2015). Browned Off and Bloody-minded: The British Soldier Goes to War 1939–1945. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17075-7.

- Bell, P. M. H. (1997) [1986]. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe (2nd ed.). London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-582-30470-3.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1973). Destination Dunkirk: The Story of Gort's Army. London: William Kimber. OCLC 816504061.

- Chaplin, Howard Douglas (1954). The Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment, 1920–1950. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 558561129.

- Chappell, Michael (1987). British Battle Insignia 1939–1940. Men-At-Arms. Vol. 2. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-739-1.

- Collier, Richard (1961). The Sands of Dunkirk. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc. OCLC 974413933.

- Ellis, Lionel F. (1954). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 1087882503.

- Fraser, David (1999) [1983]. And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in the Second World War. London: Cassell Military. ISBN 978-0-304-35233-3.

- French, David (2001) [2000]. Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War Against Germany 1919–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-24630-4.

- Gibbs, N. H. (1976). Grand Strategy. History of the Second World War. Vol. I. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-116-30181-9.

- Haswell, Jock (1967). The Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey): (The 2nd Regiment of Foot). London: H. Hamilton. OCLC 877364233.

- Horne, Alistair (2007) [1990]. To Lose a Battle: France 1940. London: Pengiun. ISBN 978-0-14103-065-4.

- Jones, Alexander David (2016). Pinchbeck Regulars? The Role and Organisation of the Territorial Army, 1919–1940 (PhD thesis). Oxford: Balliol College, University of Oxford. OCLC 974510947.

- Joslen, H. F. (2003) [1960]. Orders of Battle: Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-474-1.

- Langley, Michael (1972). The East Surrey Regiment (The 31st and 70th Regiments of Foot). London: Cooper. OCLC 1027224968.

- Levy, James P. (2006). Appeasement and Rearmament: Britain, 1936–1939. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-4537-3.

- Lord, Cliff; Watson, Graham (2003). Royal Corps of Signals: Unit Histories of the Corps (1920–2001) and its Antecedents. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-87462-207-9.

- Lynch, Tim (2010). Dunkirk 1940 'Whereabouts Unknown': How Untrained Troops of the Labour Division were Sacrificed to Save an Army. Stroud: Spellmount/The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75245-490-0.

- Martineau, G.D. (1955). A History of the Royal Sussex Regiment; A History of the Old Belfast Regiment and the Regiment of Sussex, 1701-1953. Chichester: Moore & Tillyer. OCLC 38743977.

- Messenger, Charles (1994). For Love of Regiment 1915–1994. A History of British Infantry. Vol. 2. London: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-422-2.

- Morling, L.F. (1972). Sussex Sappers: A History of the Sussex Volunteer and Territorial Army Royal Engineer Units from 1890 to 1967. Seaford: 208th Field Coy. R.E. Committee and C. Hollington. OCLC 558527345.

- Murland, Jerry (2016). Retreat & Rearguard: Dunkirk 1940: The Evacuation of the BEF to the Channel Ports. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-47382-366-2.

- Newbold, David John (1988). British Planning And Preparations To Resist Invasion on Land, September 1939 – September 1940 (PhD thesis). London: King's College London. OCLC 556820697.

- Perry, Frederick William (1988). The Commonwealth Armies: Manpower and Organisation in Two World Wars. War, Armed Forces and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71902-595-2.

- Rissik, David (2004) [1952]. The D.L.I. at War. The History of the Durham Light Infantry 1939–1945. Uckfield: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-144-0.

- Rhodes-Wood, Edward Harold (1960). A War History of the Royal Pioneer Corps, 1939–1945. Aldershot: Gale & Polden. OCLC 3164183.

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2006). Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-0-2439-7.

- Simkins, Peter (2007) [1988]. Kitchener's Army: The Raising of the New Armies 1914–1916. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-585-9.

- Smalley, Edward (2015). The British Expeditionary Force, 1939–40. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-137-49419-1.

- Story, H. H. (1961). The History of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles): 1910-1933. Slough: Hazell Watson & Viney. OCLC 758883173.

- Thompson, Julian (2009). Dunkirk. Retreat to Victory. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-1-50986-004-3.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1994). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52144-317-3.