Martial law in Taiwan

Martial law in Taiwan (Chinese: 戒嚴時期; pinyin: Jièyán Shíqí; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Kài-giâm sî-kî) refers to the periods in the history of Taiwan after World War II, during control by the Republic of China Armed Forces of the Kuomintang-led regime. The term is specifically used to refer to the over 38-year-long consecutive martial law period between 20 May 1949 and 14 July 1987, which was qualified as "the longest imposition of martial law by a regime anywhere in the world"[1] at that time (having since been surpassed by Syria[2]).

| Martial law in Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 戒嚴時期 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Declaration of Martial Law in Taiwan Province | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣省戒嚴令 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

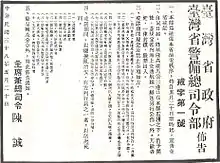

| Declaration of Martial Law in Taiwan Province 臺灣省戒嚴令 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Original title | 臺灣省政府、臺灣省警備總司令部佈告戒字第壹號 |

| Ratified | 19 May 1949 |

| Date effective | 20 May 1949 |

| Repealed | 15 July 1987 |

| Location | Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China |

| Commissioned by | Taiwan Provincial Government and Taiwan Garrison Command |

| Signatories | Chen Cheng, Chairman and Commander |

| Presidential Order on Lifting of Martial Law in Taiwan 臺灣地區解嚴令 | |

|---|---|

| |

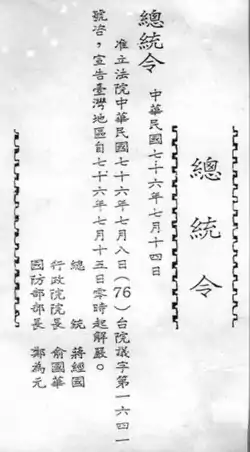

| Original title | 總統令 |

| Ratified | 14 July 1987 |

| Date effective | 15 July 1987 |

| Location | Office of the President, Taipei, Republic of China |

| Commissioned by | Government of the Republic of China |

| Signatories | Chiang Ching-kuo, President Yu Kuo-hwa, Premier Cheng Wei-yuan, Minister of National Defense |

|

|---|

|

|

With the outbreak of Chinese Civil War, the "Declaration of Martial Law in Taiwan Province" (臺灣省戒嚴令; Táiwān Shěng Jièyán Lìng; Tâi-oân-séng Kài-giâm Lēng) was enacted by Chen Cheng, who served as the chairman of Taiwan Provincial Government and commander of Taiwan Garrison Command, on 19 May 1949. This order was effective within the territory of Taiwan Province (including Island of Taiwan and Penghu).[3] The provincial martial law order was then superseded by an amendment of the "Declaration of Nationwide Martial Law", which was enacted by the central government after the amendment received a retroactive consent by the Legislative Yuan on 14 March 1950. Martial law in Taiwan Area (including Island of Taiwan, Penghu) was lifted by a Presidential order promulgated by President Chiang Ching-kuo on 15 July 1987.[4]

History of martial law under the Republic of China

The history of martial law of the Republic of China (ROC) could be dated back to the final year of the Qing dynasty. The outline of a 1908 draft constitution—modeled on Japan's Meiji Constitution—included provisions for martial law.[5] The Provisional Government of the Republic of China promulgated the Provisional Constitution in March 1911, which authorized the President to declare martial law in times of emergency. The Martial Law Declaration Act (Chinese: 戒嚴法; pinyin: Jièyánfǎ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Kài-giâm-hoat) were issued by the Nationalist Government later in 1920s and amended in 1940s. After the surrender of Japan in August 1945, the Republic of China occupied Taiwan on behalf of the Allies. The martial law was declared twice in Taiwan in 1947, due to the February 28 incident.

- The first martial law was enacted by Chen Yi, Chief Executive of Taiwan Province in 28 February. It was lifted shortly in 2 March by the request from members of the Taiwan Representative Council and the National Assembly hoping to cool down the tension.

- The incident broke out to a wide protest on economic collapse due to the Kuomintang's occupation administration. Then the second martial law was enacted by Chen Yi again in 9 March. The tension of the incidents made the Republic of China to reform the Taiwan Provincial Government. After the incident was fully repressed, the martial law was lifted on 16 May 1947 by the first Chairman of Taiwan Provincial Government Wei Tao-ming.

At the same time, the Chinese Civil War was also raging in the Republic of China. In April 1948, the newly elected National Assembly passed the Temporary Provisions against the Communist Rebellion as a constitutional amendment. This became the factual legal basis for the martial law in effect between 1948 and 1987.[6]

- The first declaration of nationwide martial law was enacted by President Chiang Kai-shek on 10 December 1948. The declaration was effective nationwide except in Sinkiang, Sikang, Tsinghai, Tibet Area and Taiwan. The territory in the north of Yangtze River was declared as the War Zone, and the south was declared as the Alert Zone. With the continuing of the civil war, Chiang resigned as president on 21 January 1949, as KMT forces suffered terrible losses and defections to the Chinese Communist Party. The Vice President Li Tsung-jen was then sworn in as the Acting President. He decided to lift the nationwide martial law in 24 January to ease the situation to conduct negotiations with the Chinese Communist Party.

- As an increasing number of refugees of the Chinese Civil War fled to Taiwan, the Declaration of Martial Law in Taiwan Province was enacted by Chen Cheng, who served as the chairman of Taiwan Provincial Government and commander of Taiwan Garrison Command, on 19 May 1949. This order was effective within the territory of Taiwan Province.

- The negotiations between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party failed. The second declaration of nationwide martial law was enacted by Acting President Li Tsung-jen on 7 July 1949.[7] This declaration also excluded the five divisions as the first declaration, but all the south-of-Yangtze provinces became War Zone, including the Fukien Province, under which (Kinmen and Matsu).

The situation became worse in later months. In September 1949, Chen Cheng then submitted a request to Premier Yen Hsi-shan, proposing to amend the second Declaration of Nationwide Martial Law to add Hainan and Taiwan into the War Zone. However, the Acting President Li Tsung-jen then fled to Hong Kong in November 1949 and did not ratify the amendment.

The outcome of the Chinese Civil War forced the Kuomintang-led Government of the Republic of China to retreat to Taiwan since 7 December 1949. On 14 March 1950, the restored session of the Legislative Yuan subsequently endorsed the second Declaration of Nationwide Martial Law along with the amendment proposed by Executive Yuan Premier Yen Hsi-shan to add Hainan and Taiwan into the War Zone. This makes the Declaration of Nationwide Martial Law supersede the provincial martial law declaration. The situation remained unchanged until 1987 Lieyu Massacre.[8]

The procedure of the ratification of the martial law declarations was significantly flawed as found by an investigation conducted by the Control Yuan.[9][10]

Influence of martial law

In December 1949, the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China retreated to Taiwan. The ROC continued to claim sovereignty over all "China", which the ROC defines to include mainland China, Taiwan, Outer Mongolia and other areas while the Communist People's Republic of China claimed to be the only China and that the ROC no longer existed. Thus, the two regimes entered a new era of confrontation and the martial law became one of the most important laws to "suppress Communist and Taiwan Independent activities in Taiwan", issuing the emergency declaration.

Also in the year 1949, a series of relevant regulations were promulgated by ROC government, including the Regulations to prevent unlawful assembly, association, procession, petition, strike under martial law, the Measures to regulate newspapers, magazines and book publication under the martial law and the Regulations for the punishment of rebellions.

Under the martial law, the formation of new political parties was prohibited except the Kuomintang (KMT), the Chinese Youth Party and the China Democratic Socialist Party. In order to implement the strict political censorship, the lianzuo or collective responsibility system was adopted among the civil servants from 9 July 1949 and soon spread to all the enterprises and institutions, according to which no one would be employed without a guarantor.

The government was authorized by the martial law to deny the right of assembly, free speech and publication in Taiwanese Hokkien. Newspapers were asked to run propaganda articles or make last-minute editorial changes to suit the government's needs. At the beginning of the martial law era, "newspapers could not exceed six pages. The number was increased to eight pages in 1958, 10 in 1967 and 12 in 1974. There were only 31 newspapers, 15 of which were owned by either the KMT, the government or the military."[11]

Taiwan Garrison Command had sweeping powers, including the right to arrest anyone voicing criticism of government policy and to screen publications prior to distribution. According to a recent report by the Executive Yuan of Taiwan, around 140,000 Taiwanese were arrested, tortured, imprisoned or executed for their real or perceived opposition to the KMT and 3000–4000 people were executed during the martial law period. Since these people were mainly from the intellectual and social elite an entire generation of political and social leaders was decimated.

Lifting of martial law

Enforcement was slowly relaxed after Chiang Kai-shek's death in 1975, but continued until the exposure of the Donggang Incident by international media reportage and the follow-up Parliament questioning by newly elected Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) members in June 1987. The lifting of martial law was proclaimed by President Chiang Ching-kuo on 14 July, followed by the liberalization and democratization of Taiwan.[12][13] Before that, the Democratic Progressive Party was illegally established in September 1986 and won 22.2% of the vote in the Legislative Yuan election and 18.9% of the vote in the National Assembly that year.[14][15][16]

Lifting of martial law permitted opposition political parties to be formed legally for the first time, giving Taiwan's fragmented but increasingly vocal opposition a new chance to organize. But even after the law was lifted, tight restrictions on freedom of assembly, speech and the press remained in place, having been written into a National Security Law, which had been passed a few days before the lifting of martial law.[17]

All declarations of martial law based on the Temporary Provisions against the Communist Rebellion were lifted when the Temporary Provisions were repealed on 1 May 1991. However, the Ministry of National Defense then issued a temporary declaration of martial law effective in the frontier region including Fukien Province (Kinmen and Matsu) and South China Sea Islands (Tungsha, and Taiping Island in Nansha). This temporary martial law was formally lifted on 7 November 1992, marking a turn to constitutional democracy for the entire Free area of the Republic of China, though the statutory restriction on civilians' traveling to Kinmen or Matsu remained effective until 13 May 1994.[18]

Compensation and memorials

In 1998, a law was passed to create the "Compensation Foundation for Improper Verdicts" which oversaw compensation to White Terror victims and families.[19][20] From 1998 to 2014, the foundation received 10,065 files. 1,940 were rejected for not relating to victims of the White Terror, as were 96 others under article 8 of the 1998 Compensation Act, whilst 7,965 applications were accepted, and 20,340 people were compensated.

In 2007, the Executive Yuan designated 15 July as "Commemoration Day of the Lifting of Martial Law".[21] President Ma Ying-jeou made an official apology in 2008, expressing hope that there would never be a tragedy similar to White Terror.[22]

See also

Notes

- Mulvenon, James C (2003). A Poverty of riches: new challenges and opportunities in PLA research. Rand Corporation. p. 172. ISBN 0-8330-3469-3.

- Barker, Anne (28 March 2011). "Syria to end 48 years of martial law". ABC/Wire. ABC News. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Han Chueng (15 May 2016). "Taiwan in Time: The precursor to total control". Taipei Times. p. 12. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- "Declaration of the Lifting of Martial Law Starting 12AM on 15 July 1987". National Central Library Gazette Online. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Mulvenon (2003), p. 171.

- 宜蘭市志—國府時期(1945~1961)

- 全國戒嚴令

- Zheng Jing, Cheng Nan-jung, Ye Xiangzhi, Xu Manqing (13 June 1987). <Shocking inside story of the Kinmen Military Murder Case>. Freedom Era Weekly, Ver 175-176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 臺灣發布戒嚴是否符合法定程序—監察院提調查報告

- 監院報告:38年戒嚴令—發布有瑕疵

- "Taiwanese Society Under Martial Law Remembered". 15 July 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Guan Ren-jian (1 September 2011). <The Taiwan you don't know: Stories of ROC Arm Forces>. Puomo Digital Publishing. ISBN 9789576636493.(in Chinese)

- "Taiwan Ends 4 Decades of Martial Law". The New York Times. Associated Press. 15 July 1987. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Copper, John F. (1987). "Taiwan in 1986: Back on Top again". Asian Survey. 27 (1): 81–91. doi:10.2307/2644602. JSTOR 2644602.

- Copper, John F. (1990). "Taiwan's Recent Elections: Fulfilling the Democratic Promise". Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies. 1990 (6): 45–64. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "Taiwan Communiqué no. 28". International Committee for Human Rights in Taiwan. January 1987. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- Gluck, Caroline (13 July 2007). "Remembering Taiwan's martial law". BBC News. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Art. 3, the Act on the Security and Assistance for Kinmen, Matsu, Tungsha, and Nansha (jinmen mazu dongsha nansha anquan ji fudao tiaoli, 金門馬祖東沙南沙地區安全及輔導條例), version in effect from 7 November 1992, to 12 May 1994. "《世紀金門百年輝煌》建縣百年 金門大事紀". 金門日報特訊月刊. 29 September 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Stolojan, Vladimir; Guill, Elizabeth (2017). "Transitional Justice and Collective Memory in Taiwan: How Taiwanese Society is Coming to Terms with Its Authoritarian Past". China Perspectives. 110 (2017/2): 27–35. doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.7327. JSTOR 26380503.

- "Compensation Act for Wrongful Trials on Charges of Sedition and Espionage during the Martial Law Period". Laws & Regulations Database of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "Chen marks 1987 martial-law abolition". Taiwan Today. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Gluck, Caroline (16 July 2008). "Taiwan sorry for white terror era". BBC News. London. Retrieved 15 December 2022.