IBM Personal Computer

The IBM Personal Computer (model 5150, commonly known as the IBM PC) is the first microcomputer released in the IBM PC model line and the basis for the IBM PC compatible de facto standard. Released on August 12, 1981, it was created by a team of engineers and designers directed by Don Estridge in Boca Raton, Florida.

| |

.png.webp) IBM Personal Computer with keyboard and monitor | |

| Manufacturer | IBM |

|---|---|

| Type | Personal Computer |

| Generation | First generation |

| Release date | August 12, 1981 |

| Introductory price | Starting at US$1,565 (equivalent to $5,040 in 2022) |

| Discontinued | April 2, 1987 |

| Operating system | |

| CPU | Intel 8088 @ 4.77 MHz |

| Memory | 16 KB – 256 KB (motherboard) |

| Graphics | MDA, CGA |

| Sound | PC speaker 1-channel square-wave/1-bit digital (PWM-capable) |

| Predecessor | IBM System/23 Datamaster |

| Successor | |

| Related | List of IBM Personal Computer models |

The machine was based on open architecture and third-party peripherals. Over time, expansion cards and software technology increased to support it.

The PC had a substantial influence on the personal computer market. The specifications of the IBM PC became one of the most popular computer design standards in the world. The only significant competition it faced from a non-compatible platform throughout the 1980s was from Apple's Macintosh product line, as well as consumer-grade platforms created by companies like Commodore and Atari. The majority of contemporary personal computers are distant descendants of the IBM PC, including the Intel-based Mac computers manufactured from 2006 to 2022.

History

Prior to the 1980s, IBM had largely been known as a provider of business computer systems.[1] As the 1980s opened, their market share in the growing minicomputer market failed to keep up with competitors, while other manufacturers were beginning to see impressive profits in the microcomputer space. The market for personal computers was dominated at the time by Tandy, Commodore, and Apple, whose machines sold for several hundred dollars each and had become very popular. The microcomputer market was large enough for IBM's attention, with $15 billion in sales by 1979 and projected annual growth of more than 40% during the early 1980s. Other large technology companies had entered it, such as Hewlett-Packard, Texas Instruments and Data General, and some large IBM customers were buying Apples.[2][3]

As early as 1980 there were rumors of IBM developing a personal computer, possibly a miniaturized version of the IBM System/370,[4] and Matsushita acknowledged publicly that it had discussed with IBM the possibility of manufacturing a personal computer in partnership, although this project was abandoned.[5][6] The public responded to these rumors with skepticism, owing to IBM's tendency towards slow-moving, bureaucratic business practices tailored towards the production of large, sophisticated and expensive business systems.[7] As with other large computer companies, its new products typically required about four to five years for development,[8][9] and a well publicized quote from an industry analyst was, "IBM bringing out a personal computer would be like teaching an elephant to tap dance."[10]

IBM had previously produced microcomputers, such as 1975's IBM 5100, but targeted them towards businesses; the 5100 had a price tag as high as $20,000.[11] Their entry into the home computer market needed to be competitively priced.

In 1980, IBM president John Opel, recognizing the value of entering this growing market, assigned William C. Lowe to the new Entry Level Systems unit in Boca Raton, Florida. Market research found that computer dealers were very interested in selling an IBM product, but they insisted the company use a design based on standard parts, not IBM-designed ones so that stores could perform their own repairs rather than requiring customers to send machines back to IBM for service.[12]

Atari proposed to IBM in 1980 that it act as original equipment manufacturer for an IBM microcomputer,[13] a potential solution to IBM's known inability to move quickly to meet a rapidly changing market. The idea of acquiring Atari was considered but rejected in favor of a proposal by Lowe that by forming an independent internal working group and abandoning all traditional IBM methods, a design could be delivered within a year and a prototype within 30 days. The prototype worked poorly but was presented with a detailed business plan which proposed that the new computer have an open architecture, use non-proprietary components and software, and be sold through retail stores, all contrary to IBM practice. It also estimated sales of 220,000 computers over three years, more than IBM's entire installed base.[14][15]

This swayed the Corporate Management Committee, which converted the group into a business unit named "Project Chess", and provided the necessary funding and authority to do whatever was needed to develop the computer in the given timeframe. The team received permission to expand to 150 people by the end of 1980, and in one day more than 500 IBM employees called in asking to join.

Design process

The design process was kept under a policy of strict secrecy, with all other IBM divisions kept in the dark about the project.[16]

Several CPUs were considered, including the Texas Instruments TMS9900, Motorola 68000 and Intel 8088. The 68000 was considered the best choice,[17] but was not production-ready like the others.[18] The IBM 801 RISC processor was also considered, since it was considerably more powerful than the other options, but rejected due to the design constraint to use off-the-shelf parts.

IBM chose the 8088 over the similar but superior 8086 because Intel offered a better price for the former and could provide more units,[19] and the 8088's 8-bit bus reduced the cost of the rest of the computer. The 8088 had the advantage that IBM already had familiarity with the 8085 from designing the IBM System/23 Datamaster. The 62-pin expansion bus slots were also designed to be similar to the Datamaster slots,[20] and its keyboard design and layout became the Model F keyboard shipped with the PC,[21] but otherwise the PC design differed in many ways.

The 8088 motherboard was designed in 40 days,[22] with a working prototype created in four months,[23] demonstrated in January 1981. The design was essentially complete by April 1981, when it was handed off to the manufacturing team.[24] PCs were assembled in an IBM plant in Boca Raton, with components made at various IBM and third party factories. The monitor was an existing design from IBM Japan; the printer was manufactured by Epson.[25] Because none of the functional components were designed by IBM, they obtained no patents on the PC.[26]

Many of the designers were computer hobbyists who owned their own computers,[8] including many Apple II owners, which influenced the decisions to design the computer with an open architecture[27] and publish technical information so others could create compatible software and expansion slot peripherals.[28]

During the design process IBM avoided vertical integration as much as possible, for example choosing to license Microsoft BASIC rather than utilizing the in-house version of BASIC used for mainframes due to the better existing public familiarity with the Microsoft version.[29]

Debut

The IBM PC debuted on August 12, 1981 after a twelve-month development. Pricing started at $1,565 for a configuration with 16 KB RAM, Color Graphics Adapter, and no disk drives. The price was designed to compete with comparable machines in the market.[30] For comparison, the Datamaster, announced two weeks earlier as IBM's least expensive computer, cost $10,000.[31]

IBM's marketing campaign licensed the likeness of Charlie Chaplin's character "The Little Tramp" for a series of advertisements based on Chaplin's movies, played by Billy Scudder.[32]

The PC was IBM's first attempt to sell a computer through retail channels rather than directly to customers. Because IBM did not have retail experience, they partnered with the retail chains ComputerLand and Sears, who provided important knowledge of the marketplace[33][34][35][36] and became the main outlets for the PC. More than 190 ComputerLand stores already existed, while Sears was in the process of creating a handful of in-store computer centers for sale of the new product.

Reception was overwhelmingly positive, with analysts estimating sales volume in the billions of dollars in the first few years after release.[37] After release, IBM's PC immediately became the talk of the entire computing industry.[38] Dealers were overwhelmed with orders, including customers offering pre-payment for machines with no guaranteed delivery date.[30] By the time the machine began shipping, the term "PC" was becoming a household name.[39]

Success

Sales exceeded IBM's expectations by as much as 800%, with the company at one point shipping as many as 40,000 PCs per month.[40] IBM estimated that home users made up 50 to 70% of purchases from retail stores.[41] In 1983, IBM sold more than 750,000 machines,[42] while Digital Equipment Corporation, one of the companies whose success had spurred IBM to enter the market, sold only 69,000.[43]

Software support from the industry grew rapidly, with the IBM nearly instantly becoming the primary target for most microcomputer software development.[31] One publication counted 753 software packages available a year after the PC's release, four times as many as were available for the Macintosh a year after its launch.[44] Hardware support also grew rapidly, with 30–40 companies competing to sell memory expansion cards within a year.[45]

By 1984, IBM's revenue from the PC market was $4 billion, more than twice that of Apple.[46] A 1983 study of corporate customers found that two thirds of large customers standardizing on one computer chose the PC, while only 9% chose Apple.[47] A 1985 Fortune survey found that 56% of American companies with personal computers used PCs while 16% used Apple.[48]

Almost as soon as the PC reached the market, rumors of clones began,[49] and the first PC compatible clone was released in June 1982, less than a year after the PC's debut.

Eventually, IBM sold its PC business to Lenovo in 2004.

Hardware

For low cost and a quick design turnaround time, the hardware design of the IBM PC used entirely "off-the-shelf" parts from third party manufacturers, rather than unique hardware designed by IBM.[50]

The PC is housed in a wide, short steel chassis intended to support the weight of a CRT monitor. The front panel is made of plastic, with an opening where one or two disk drives can be installed. The back panel houses a power inlet and switch, a keyboard connector, a cassette connector and a series of tall vertical slots with blank metal panels which can be removed in order to install expansion cards.

Internally, the chassis is dominated by a motherboard which houses the CPU, built-in RAM, expansion RAM sockets, and slots for expansion cards.

The IBM PC was highly expandable and upgradeable, but the base factory configuration included:

| CPU | Intel 8088 @ 4.77 MHz |

|---|---|

| RAM | 16 KB or 64 KB (expandable to 256 KB) |

| Video | IBM Monochrome Display Adapter or |

| Display | IBM 5151 monochrome display

IBM 5153 color display Composite-input television |

| Input | IBM Model F 83-key keyboard with five-pin connector |

| Sound | Single programmable-frequency square wave with built-in speaker |

| Storage | Up to two 5.25-inch, 160 KB/320 KB (single/double sided) floppy disk drives

Port for attaching to cassette tape recorder Optional hard disk drive |

| Expansion | Five 62-pin expansion slots attached to 8-bit CPU I/O bus

IBM 5161 Expansion Chassis with eight (seven usable) extra I/O slots |

| Communication | Optional serial and parallel ports |

Motherboard

The PC is built around a single large circuit board called a motherboard which carries the processor, built-in RAM, expansion slots, keyboard and cassette ports, and the various peripheral integrated circuits that connected and controlled the components of the machine.

The peripheral chips included an Intel 8259 PIC, an Intel 8237 DMA controller, and an Intel 8253 PIT. The PIT provides 18.2 Hz clock "ticks" and dynamic memory refresh timing.

CPU and RAM

.jpg.webp)

The CPU is an Intel 8088, a cost-reduced form of the Intel 8086 which largely retains the 8086's internal 16-bit logic, but exposes only an 8-bit bus.[51] The CPU is clocked at 4.77 MHz, which would eventually become an issue when clones and later PC models offered higher CPU speeds that broke compatibility with software developed for the original PC.[52] The single base clock frequency for the system was 14.31818 MHz, which when divided by 3, yielded the 4.77 MHz for the CPU (which was considered close enough to the then 5 MHz limit of the 8088), and when divided by 4, yielded the required 3.579545 MHz for the NTSC color carrier frequency.

The PC motherboard included a second, empty socket, described by IBM simply as an "auxiliary processor socket", although the most obvious use was the addition of an Intel 8087 math coprocessor, which improved floating-point math performance.[53]

From the factory the PC was equipped with either 16 KB or 64 KB of RAM. RAM upgrades were provided both by IBM and third parties as expansion cards, and could upgrade the machine to a maximum of 256 KB on the motherboard, and 640 KB total.[51]

ROM BIOS

The BIOS is the firmware of the IBM PC, occupying one 8 KB chip on the motherboard. It provides bootstrap code and a library of common functions that all software can use for many purposes, such as video output, keyboard input, disk access, interrupt handling, testing memory, and other functions. IBM shipped three versions of the BIOS throughout the PC's lifespan.

Display

While most home computers had built-in video output hardware, IBM took the unusual approach of offering two different graphics options, the MDA and CGA cards. The former provided high-resolution monochrome text, but could not display anything except text, while the latter provided medium- and low-resolution color graphics and text.

CGA used the same scan rate as NTSC television, allowing it to provide a composite video output which could be used with any compatible television or composite monitor, as well as a direct-drive TTL output suitable for use with any RGBI monitor using an NTSC scan rate. IBM also sold the 5153 color monitor for this purpose, but it was not available at release[54] and was not released until March 1983.[55]

MDA scanned at a higher frequency and required a proprietary monitor, the IBM 5151. The card also included a built-in printer port.[56]

Both cards could also be installed simultaneously for mixed graphics and text applications.[57] For instance, AutoCAD, Lotus 1-2-3 and other software allowed use of a CGA Monitor for graphics and a separate monochrome monitor for text menus. Third parties went on to provide an enormous variety of aftermarket graphics adapters, such as the Hercules Graphics Card.

The software and hardware of the PC, at release, was designed around a single 8-bit adaptation of the ASCII character set, now known as code page 437.

Storage

The two bays in the front of the machine could be populated with one or two 5.25″ floppy disk drives, storing 160 KB per disk side for a total of 320 KB of storage on one disk.[56] The floppy drives require a controller card inserted in an expansion slot, and connect with a single ribbon cable with two edge connectors. The IBM floppy controller card provides an external 37-pin D-sub connector for attachment of an external disk drive, although IBM did not offer one for purchase until 1986.

As was common for home computers of the era, the IBM PC offered a port for connecting a cassette data recorder. Unlike the typical home computer however, this was never a major avenue for software distribution,[58] probably because very few PCs were sold without floppy drives. The port was removed on the very next PC model, the XT.[59]

At release, IBM did not offer any hard disk drive option[51] and adding one was difficult - the PC's stock power supply had inadequate power to run a hard drive, the motherboard did not support BIOS expansion ROMs which was needed to support a hard drive controller, and both PC DOS and the BIOS had no support for hard disks. After the XT was released, IBM altered the design of the 5150 to add most of these capabilities, except for the upgraded power supply. At this point adding a hard drive was possible, but required the purchase of the IBM 5161 Expansion Unit, which contained a dedicated power supply and included a hard drive.[60]

Although official hard drive support did not exist, the third party market did provide early hard drives that connected to the floppy disk controller, but required a patched version of PC DOS to support the larger disk sizes.

Human interface

The only option for human interface provided in the base PC was the built-in keyboard port, meant to connect to the included Model F keyboard. The Model F was initially developed for the IBM Datamaster, and was substantially better than the keyboards provided with virtually all home computers on the market at that time in many regards - number of keys, reliability and ergonomics. While some home computers of the time utilized chiclet keyboards or inexpensive mechanical designs, the IBM keyboard provided good ergonomics, reliable and positive tactile key mechanisms and flip-up feet to adjust its angle. Public reception of the keyboard was extremely positive, with some sources describing it as a major selling point of the PC and even as "the best keyboard available on any microcomputer."[56]

At release, IBM provided a Game Control Adapter which offered a 15-pin port intended for the connection of up to two joysticks, each having two analog axes and two buttons. (The early PCs predated the advent of the "Windows, Icons, Mouse, Pointer concept and so did not have a mouse.)

Communications

Connectivity to other computers and peripherals was initially provided through serial and parallel ports.

IBM provided a serial card based on an 8250 UART. The BIOS supports up to two serial ports.

IBM provided two different options for connecting Centronics-compatible parallel printers. One was the IBM Printer Adapter, and the other was integrated into the MDA as the IBM Monochrome Display and Printer Adapter.

Expansion

The expansion capability of the IBM PC was very significant to its success in the market. Some publications highlighted IBM's uncharacteristic decision to publish complete, thorough specifications of the system bus and memory map immediately on release, with the intention of fostering a market of compatible third-party hardware and software.[61]

The motherboard includes five 62-pin card edge connectors which are connected to the CPU's I/O lines. IBM referred to these as "I/O slots," but after the expansion of the PC clone industry they became retroactively known as the ISA bus. At the back of the machine is a metal panel, integrated into the steel chassis of the system unit, with a series of vertical slots lined up with each card slot.

Most expansion cards have a matching metal bracket which slots into one of these openings, serving two purposes. First, a screw inserted through a tab on the bracket into the chassis fastens the card securely in place, preventing the card from wiggling out of place. Second, any ports the card provides for external attachment are bolted to the bracket, keeping them secured in place as well.

The PC expansion slots can accept an enormous variety of expansion hardware, adding capabilities such as:

- Graphics

- Sound

- Mouse support

- Expanded memory

- Additional serial or parallel ports

- Networking

- Connection to proprietary industrial or scientific equipment

The market reacted as IBM had intended, and within a year or two of the PC's release the available options for expansion hardware were immense.

5161 Expansion Unit

The expandability of the PC was important, but had significant limitations.

One major limitation was the inability to install a hard drive, as described above. Another was that there were only five expansion slots, which tended to get filled up by essential hardware - a PC with a graphics card, memory expansion, parallel card and serial card was left with only one open slot, for instance.

IBM rectified these problems in the later XT, which included more slots and support for an internal hard drive, but at the same time released the 5161 Expansion Unit, which could be used with either the XT or the original PC. The 5161 connected to the PC system unit using a cable and a card plugged into an expansion slot, and provided a second system chassis with more expansion slots and a hard drive.

Software

IBM initially announced intent to support multiple operating systems: CP/M-86, UCSD p-System,[62] and an in-house product called IBM PC DOS, based on 86-DOS from Seattle Computer Products and provided by Microsoft.[63][8] In practice, IBM's expectation and intent was for the market to primarily use PC DOS,[64] CP/M-86 was not available for six months after the PC's release[65] and received extremely few orders once it was,[66] and p-System was also not available at release. PC DOS rapidly established itself as the standard OS for the PC and remained the standard for over a decade, with a variant being sold by Microsoft themselves as MS-DOS.

The PC included BASIC in ROM (four 8 KB chips), a common feature of 1980s home computers. Its ROM BASIC supported the cassette tape interface, but PC DOS did not, limiting use of that interface to BASIC only.

PC DOS version 1.00 supported only 160 KB SSDD floppies, but version 1.1, which was released nine months after the PC's introduction, supported 160 KB SSDD and 320 KB DSDD floppies. Support for the slightly larger nine sector per track 180 KB and 360 KB formats was added in March 1983.

Third-party software support grew extremely quickly, and within a year the PC platform was supplied with a vast array of titles for any conceivable purpose.

Reception

Reception of the IBM PC was extremely positive. Even before its release reviewers were impressed by the advertised specifications of the machine, and upon its release reviews praised virtually every aspect of its design both in comparison to contemporary machines and with regards to new and unexpected features.

Praise was directed at the build quality of the PC, in particular its keyboard, IBM's decision to use open specifications to encourage third party software and hardware development, their speed at delivering documentation and the quality therein, the quality of the video display, and the use of commodity components from established suppliers in the electronics industry.[67] The price was considered extremely competitive compared to the value per dollar of competing machines.[54]

Two years after its release, Byte magazine retrospectively concluded that the PC had succeeded both because of its features – an 80-column screen, open architecture, and high-quality keyboard – and the failure of other computer manufacturers to achieve these features first:

In retrospect, it seems IBM stepped into a void that remained, paradoxically, at the center of a crowded market.[68]

Creative Computing that year named the PC the best desktop computer between $2,000 and $4,000, praising its vast hardware and software selection, manufacturer support, and resale value.[69]

Many IBM PCs remained in service long after their technology became largely obsolete. For instance, as of June 2006 (23–25 years after release) IBM PC and XT models were still in use at the majority of U.S. National Weather Service upper-air observing sites, processing data returned from radiosondes attached to weather balloons.

Due to its status as the first entry in the extremely influential PC industry, the original IBM PC remains valuable as a collector's item. As of 2007, the system had a market value of $50–$500.[70]

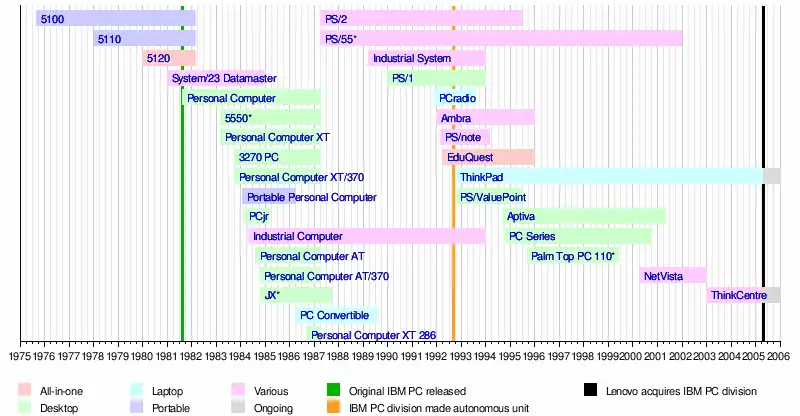

Model line

IBM sold a number of computers under the "Personal Computer" or "PC" name throughout the 80s. The name was not used for several years before being reused for the IBM PC Series in the 90s and early 2000s.

| Model name | Model # | Introduced | Discontinued | CPU | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 5150 | August 1981 | April 1987 | 8088 | Floppy disk or cassette system.[71] One or two internal floppy drives were optional. |

| XT | 5160 | March 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | First IBM PC to come with an internal hard drive as standard. |

| XT/370 | 5160/588 | October 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | 5160 with XT/370 Option Kit and 3277 Emulation Adapter. |

| 3270 PC | 5271 | October 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | With 3270 terminal emulation, 20 function key keyboard |

| PCjr | 4860 | November 1983 | March 1985 | 8088 | Floppy-based home computer, but also used ROM cartridges; infrared keyboard. |

| Portable | 5155 | February 1984 | April 1986 | 8088 | Floppy-based portable |

| AT | 5170 | August 1984 | April 1987 | 80286 | Faster processor, faster system bus (6 MHz, later 8 MHz, vs 4.77 MHz), jumperless configuration, real-time clock. |

| AT/370 | 5170/599 | October 1984 | April 1987 | 80286 | 5170 with AT/370 Option Kit and 3277 Emulation Adapter. |

| 3270 AT | 5281 | June 1985[72] | April 1987 | 80286 | With 3270 terminal emulation. |

| Convertible | 5140 | April 1986 | August 1989 | 80C88 | Microfloppy laptop portable |

| XT 286 | 5162 | September 1986 | April 1987 | 80286 | Slow hard disk, but zero wait state memory on the motherboard. This 6 MHz model is faster than the 8 MHz AT models (when using planar memory) because of its zero wait state memory. |

As with all PC-derived systems, all IBM PC models are nominally software-compatible, although some timing-sensitive software will not run correctly on models with faster CPUs.

Clones

Because the IBM PC was based on commodity hardware rather than unique IBM components, and because its operation was extensively documented by IBM, creating machines that were fully compatible with the PC offered few challenges other than the creation of a compatible BIOS ROM.

Simple duplication of the IBM PC BIOS was a direct violation of copyright law, but soon into the PC's life the BIOS was reverse-engineered by companies like Compaq, Phoenix Software Associates, American Megatrends and Award, who either built their own computers that could run the same software and use the same expansion hardware as the PC, or sold their BIOS code to other manufacturers who wished to build their own machines.

These machines became known as IBM compatibles or "clones", and software was widely marketed as compatible with "IBM PC or 100% compatible". Shortly thereafter, clone manufacturers began to make improvements and extensions to the hardware, such as by using faster processors like the NEC V20, which executed the same software as the 8088 at a higher speed up to 10 MHz.

The clone market eventually became so large that it lost its associations with the original PC and became a set of de facto standards established by various hardware manufacturers.

Timeline

| Timeline of the IBM Personal Computer |

|---|

|

| Asterisk (*) denotes a model released in Japan only |

References

- Cited references

- Pollack, Andrew (August 13, 1981). "Big I.B.M.'s Little Computer". The New York Times. p. D1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- Morgan, Christopher P (March 1980). "Hewlett-Packard's New Personal Computer". Byte. p. 60. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- Swaine, Michael (October 5, 1981). "Tom Swift Meets the Big Boys: Small Firms Beware". InfoWorld. p. 45. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- "Interest Group for Possible IBM Computer". Byte. January 1981. p. 313. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- Libes, Sol (June 1981). "IBM and Matsushita to Join Forces?". Byte. p. 208. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- Morgan, Chris (July 1981). "IBM's Personal Computer". Byte. p. 6. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "IBM 5120". IBM. January 23, 2003. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- Morgan, Chris (January 1982). "Of IBM, Operating Systems, and Rosetta Stones". Byte. p. 6. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Bunnell, David (February–March 1982). "The Man Behind The Machine? / A PC Exclusive Interview With Software Guru Bill Gates". PC Magazine. p. 16. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- "IBM Archives: The birth of the IBM PC". www.ibm.com. January 23, 2003. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- "Obsolete Technology Website". Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Blaxill, Mark; Eckardt, Ralph (2009). The Invisible Edge: Taking Your Strategy to the Next Level Using Intellectual Property. Penguin Group. pp. 195–198. ISBN 9781591842378.

- Musil, Steven (October 28, 2013). "William Lowe, the 'father of the IBM PC,' dies at 72". CNet. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- Atkinson, P, (2013) DELETE: A Design History of Computer Vapourware Archived March 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Scott, Greg (October 1988). ""Blue Magic": A Review". U-M Computing News. 3 (19): 12–15.

- "IBM PC Announcement 1981". www.bricklin.com. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Gates, Bill (March 25, 1997). "Interview: Bill Gates, Microsoft". PC Magazine (Interview). Interviewed by Michael J. Miller. Archived from the original on August 23, 2001. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Rhines, Walden C. (June 22, 2017). "The Inside Story of Texas Instruments' Biggest Blunder: The TMS9900 Microprocessor". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- Freiberger, Paul (August 23, 1982). "Bill Gates, Microsoft and the IBM Personal Computer". InfoWorld. p. 22. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- John Titus (September 15, 2001). "Whence Came the IBM PC". edn.com. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Bradley, David J. (September 1990). "The Creation of the IBM PC". Byte. pp. 414–420. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "Remembering the Beginning". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on February 6, 2002. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Sanger, David E. (August 5, 1985). "Philip Estridge Dies in Jet Crash; Guided Ibm Personal Computer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- "IBM Archives: The birth of the IBM PC". www.ibm.com. January 23, 2003. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- U-M Computing News. Computing Center. 1988.

- "Let's Keep Those Systems Open". InfoWorld. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. August 23, 1982. p. 21 – via Google Books.

- Porter, Martin (September 18, 1984). "Ostracized PC1 Designer Still Ruminates 'Why?'". PC Magazine. p. 33. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Greenwald, John (July 11, 1983). "The Colossus That Works". TIME. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- Curran, Lawrence J.; Shuford, Richard S. (November 1983). "IBM's Estridge". Byte. pp. 88–97. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- "The birth of the IBM PC". IBM Archives. January 23, 2003. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- Pollack, Andrew (27 March 1983). "Big I.B.M. Has Done It Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Papson, Stephen (April 1990). "The IBM tramp". Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media (35): 66–72.

- Mace, Scott (October 5, 1981). "Where You Can Go to Purchase the New Computers". InfoWorld. p. 49. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Sandler, Corey (November 1984). "IBM: Colossus of Armonk". Creative Computing. p. 298. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- Elder, Tait (July 1989). "New Ventures: Lessons from Xerox and IBM". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- McMullen, Barbara E.; John F. (February 21, 1984). "Apple Charts The Course For IBM". PC Magazine. p. 122. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- "Billion Dollar Baby". PC. February–March 1982. p. 5. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- Bunnell, David (February 3, 1982). "Flying Upside Down". PC Magazine. p. 10. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- Edlin, Jim; Bunnell, David (February–March 1982). "IBM's New Personal Computer: Taking the Measure / Part One". PC Magazine. p. 42. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Hayes, Thomas C. (October 24, 1983). "Eagle Computer Stays in the Race". The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Burton, Kathleen (March 1983). "Anatomy of a Colossus, Part III". PC. p. 467. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- "Origin of the IBM PC". Low End Mac. August 12, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Ahl, David H. (March 1984). "Digital". Creative Computing. pp. 38–41. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- Watt, Peggy; McGeever, Christine (January 14, 1985). "Macintosh Vs. IBM PC At One Year". InfoWorld. pp. 16–17. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- Markoff, John (August 23, 1982). "Competition and innovation mark IBM add-in market". InfoWorld. p. 20. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- Libes, Sol (September 1985). "The Top Ten". Byte. p. 418. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Byte Magazine Volume 09 Number 09 - Guide to the IBM PCs. September 1984.

- Porter, Martin (September 18, 1984). "Ostracized PC1 Designer Still Ruminates 'Why?'". PC Magazine. Vol. 3, no. 18. p. 33. Retrieved October 25, 2013 – via Google Books.

- "PCommuniques". PC Magazine. February–March 1982. p. 5. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Henderson, Harry (2009). Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. Infobase Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4381-1003-5.

- Byte Magazine Volume 06 Number 10 - Local Networks. October 1981. pp. 28–34.

- Graves, Michael W. (September 17, 2004). A+ Guide to PC Hardware Maintenance and Repair. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4018-5230-6.

- Byte Magazine Volume 07 Number 01 - The IBM Personal Computer. January 1982.

- Williams, Gregg (January 1982). "A Closer Look at the IBM Personal Computer". Byte. p. 36. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- International Business Machines Corporation (1983): Announcement Letter Number 183-002 - IBM COLOR DISPLAY, 5153. Dated February 4, 1983. http://www-01.ibm.com/common/ssi/ShowDoc.wss?docURL=/common/ssi/rep_ca/2/897/ENUS183-002/index.html&lang=en&request_locale=en

- Byte Magazine Volume 07 Number 01 - The IBM Personal Computer. January 1982.

- "Dual-Head operation on vintage PCs". www.seasip.info. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- The Peter Norton Programmer's Guide to the IBM PC. Microsoft Corporation. 1985. ISBN 0914845462.

I have never encountered a PC program on tape for sale. In fact, about the only use of the cassette port that I am aware of is the homespun and jerry-rigged use of this port as a poor-man's serial port.

- Robert, Brenner (1989). IBM Personal Computer: Troubleshooting & Repair for the IBM PC, PC/XT, and PC AT. Sams. ISBN 0672226626.

Next to the keyboard connector is a 5-pin circular connector for cassette data input/output. This connection is not available on the XT or AT.

- "minuszerodegrees.net". www.minuszerodegrees.net. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Byte Magazine Volume 07 Number 01 - The IBM Personal Computer. January 1982.

- Byte Magazine Volume 07 Number 01 - The IBM Personal Computer. January 1982.

- Freiberger, Paul (October 5, 1981). "Some Confusion at the Heart of IBM Microcomputer / Which Operating System Will Prevail?". InfoWorld. pp. 50–51. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Bunnell, David (April–May 1982). "Boca Diary". PC Magazine. p. 22. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- Edlin, Jim (June–July 1982). "CP/M Arrives". PC Magazine. p. 43. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- "PCommuniques". PC Magazine. February 1983. p. 53. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- Lemmons, Phil (October 1981). "The IBM Personal Computer / First Impressions". Byte. p. 36. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Lemmons, Phil (Fall 1984). "IBM and Its Personal Computers". Byte. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- Ahl, David H. (December 1984). "Top 12 computers of 1984". Creative Computing. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- McCracken, Harry (August 27, 2007). "The Most Collectible PCs of All Time". PCWorld. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- IBM did not offer own brand cassette recorders, but the 5150 had a cassette player jack, and IBM anticipated that entry-level home users would connect their own cassette recorders for data storage instead of using the more expensive floppy drives (and use their existing TV sets as monitors); to this end, IBM initially offered the 5150 in a basic configuration without any floppy drives or monitor at the price of $1,565, whereas they offered a system with a monitor and single floppy drive for an initial $3,005. Few if any users however bought IBM 5150 PCs without floppy drives.

- Scott Mueller, Upgrading and Repairing PCs, 2nd Ed, Que Books 1992,ISBN 0-88022-856-3, page 94

External links

- IBM SCAMP

- IBM 5150 information at www.minuszerodegrees.net

- IBM PC 5150 System Disks and ROMs

- IBM PC from IT Dictionary

- IBM PC history and technical information

- What a legacy! The IBM PC's 25 year legacy

- CNN.com - IBM PC turns 25

- IBM-5150 and collection of old digital and analog computers at oldcomputermuseum.com

- IBM PC images and information Archived July 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- A brochure from November, 1982 advertising the IBM PC

- A Picture of the XT/370 cards, showing the dual 68000 processors Archived December 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine