History of Sheffield

The history of Sheffield, a city in South Yorkshire, England, can be traced back to the founding of a settlement in a clearing beside the River Sheaf in the second half of the 1st millennium AD. The area now known as Sheffield had seen human occupation since at least the last ice age, but significant growth in the settlements that are now incorporated into the city did not occur until the Industrial Revolution.

Following the Norman conquest of England, Sheffield Castle was built to control the Saxon settlements and Sheffield developed into a small town, no larger than Sheffield City Centre. By the 14th century Sheffield was noted for the production of knives, and by 1600, overseen by the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire, it had become the second centre of cutlery production in England after London. In the 1740s the crucible steel process was improved by Sheffield resident Benjamin Huntsman, allowing a much better production quality. At about the same time, Sheffield plate, a form of silver plating, was invented. The associated industries led to the rapid growth of Sheffield; the town was incorporated as a borough in 1843 and granted a city charter in 1893.

Sheffield remained a major industrial city throughout the first half of the 20th century, but the downturn in world trade following the 1973 oil crisis, technological improvements and economies of scale, and a wide-reaching restructuring of steel production throughout the European Economic Community led to the closure of many of the steelworks from the early 1970s onward. Urban and economic regeneration schemes began in the late 1980s to diversify the city's economy. Sheffield is now a centre for banking and insurance functions with HSBC, Santander and Aviva having regional offices in the city. The city has also attracted digital start-ups, with 25,000 now employed in the digital sector.

Early history

The earliest known evidence of human occupation in the Sheffield area was found at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire to the east of the city. Artefacts and rock art found in caves at this site have been dated by archaeologists to the late Upper Palaeolithic period, at least 12,800 years ago.[1][2] Other prehistoric remains found in Sheffield include a Mesolithic "house"—a circle of stones in the shape of a hut-base dating to around 8000 BC, found at Deepcar, in the northern part of the city. This has been ascribed to the Maglemosian culture. (grid reference SK 2920 9812).[3][4] The site's culture has similarities to Star Carr in North Yorkshire, but gives its name to unique "Deepcar type assemblages"[5] of microliths in the archaeology literature. A cup and ring-marked stone was discovered in Ecclesall Woods in 1981, and has been dated to the late Neolithic or Bronze Age periods. It, and an area around it of 2 m diameter, is a scheduled ancient monument.[6]

During the Bronze Age (about 1500 BC) tribes sometimes called the Urn people started to settle in the area. They built numerous stone circles, examples of which can be found on Ash Cabin Flat, Froggatt Edge and Hordron Edge (Hordron Edge stone circle). Two Early Bronze Age urns were found at Crookes in 1887,[7][8] and three Middle Bronze Age barrows found at Lodge Moor[9] (both suburbs of the modern city).

Iron Age

During the British Iron Age the area became the southernmost territory of the Pennine tribe called the Brigantes. It is this tribe who in around 500 BC are thought to have constructed the hill fort that stands on the summit of a steep hill above the River Don at Wincobank, in what is now northeastern Sheffield.[8] Other Iron Age hill forts in the area are Carl Wark on Hathersage Moor to the southwest of Sheffield,[10] and one at Scholes Wood, near Rotherham. The rivers Sheaf and Don may have formed the boundary between the territory of the Brigantes and that of a rival tribe called the Corieltauvi who inhabited a large area of the northeastern Midlands.[11]

Roman Britain

The Roman invasion of Britain began in AD 43. By 51 the Brigantes had submitted to the clientship of Rome,[12] eventually being placed under direct rule in the early 70s.[13] Few Roman remains have been found in the Sheffield area. A minor Roman road linking the Roman forts at Templeborough and Navio at Brough-on-Noe possibly ran through the centre of the area covered by the modern city,[14] and Icknield Street is thought to have skirted its boundaries.[15][16] The routes of these roads within this area are mostly unknown, although sections of the former were thought, by Hunter and Leader,[15][17] be visible between Redmires and Stanage on an ancient road known as the Long Causeway. In recent years some scholars have cast doubt on this, with an initial survey of Barber Fields, Ringinglow, suggesting the Roman Road took a route over Burbage Edge.[18][19] The remains of a Roman road, possibly linked to the latter, were discovered in Brinsworth in 1949.[20][21]

In April 1761, tablets or diplomas dating from the Roman period were found in the Rivelin Valley south of Stannington, close to what was possibly the course of the Templeborough to Brough-on-Noe road. These tablets included a grant of citizenship and land or money to a retiring Roman auxiliary of the Sunuci tribe of Belgium.

To . . . . . . . . the son of Albanus, of the tribe of the Sunuci, late a foot soldier in the first cohort of the Sunuci commanded by M. Junius Claudianus.[22]

In addition there have been finds dating from the Roman period on Walkley Bank Road, which leads onto the valley bottom.[n 1]

There have been small finds of Roman coins throughout the Sheffield area, for example 30 to 40 Roman coins were found near the Old Great Dam at Crookesmoor,[24] 19 coins were found near Meadowhall in 1891,[25] 13 in Pitsmoor in 1906,[26] and ten coins were found at a site alongside Eckington cemetery in December 2008.[27] Roman burial urns were also found at Bank Street near Sheffield Cathedral, which, along with the name of the old lane behind the church (Campo Lane[n 2]), has led to speculation that there may have been a Roman camp at this site.[n 3] It is unlikely that the settlement that grew into Sheffield existed at this time. In 2011 excavations revealed remains of a substantial 1st or 2nd century AD Roman rural estate centre, or 'villa' on what is believed to be a pre-existing Brigantian farmstead site at Whirlow Hall Farm in South-west Sheffield.[28]

Following the departure of the Romans, the Sheffield area may have been the southern part of the Celtic kingdom of Elmet,[29] with the rivers Sheaf and Don forming part of the boundary between this kingdom and the kingdom of Mercia.[30] Gradually, Anglian settlers pushed west from the kingdom of Deira. The Britons of Elmet delayed this English expansion into the early part of the 7th century.[29] An enduring Celtic presence within this area is evidenced by the settlements called Wales and Waleswood close to Sheffield—the word Wales derives from the Germanic word Walha, and was originally used by the Anglo-Saxons to refer to the native Britons.[n 4]

The origins of Sheffield

The name Sheffield is Old English in origin.[31] It derives from the River Sheaf, whose name is a corruption of shed or sheth, meaning to divide or separate.[32] Field is a generic suffix deriving from the Old English feld, meaning a forest clearing.[33] It is likely then that the origin of the present-day city of Sheffield is an Anglo-Saxon settlement in a clearing beside the confluence of the rivers Sheaf and Don founded between the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in this region (roughly the 6th century) and the early 9th century.[34]

The names of many of the other areas of Sheffield likely to have been established as settlements during this period end in ley, which signifies a clearing in the forest, or ton, which means an enclosed farmstead.[35] These settlements include Heeley, Longley, Norton, Owlerton, Southey, Tinsley, Totley, Treeton, Wadsley, and Walkley.

The earliest evidence of this settlement is thought to be the shaft of a stone cross dating from the early 9th century[36] that was found in Sheffield in the early 19th century. This shaft may be part of a cross removed from the church yard of the Sheffield parish church (now Sheffield Cathedral) in 1570.[37] It is now kept in the British Museum.[38]

A document from around the same time, an entry for the year 829 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, refers to the submission of King Eanred of Northumbria to King Egbert of Wessex at the hamlet of Dore (now a suburb of Sheffield): "Egbert led an army against the Northumbrians as far as Dore, where they met him, and offered terms of obedience and subjection, on the acceptance of which they returned home". This event made Egbert the first Saxon to claim to be king of all of England.[39]

The latter part of the 9th century saw a wave of Norse (Viking) settlers and the subsequent establishment of the Danelaw. The names of hamlets established by these settlers often end in thorpe, which means a farmstead.[40] Examples of such settlements in the Sheffield area are Grimesthorpe, Hackenthorpe, Jordanthorpe, Netherthorpe, Upperthorpe, Waterthorpe, and Woodthorpe.[41] By 918 the Danes south of the Humber had submitted to Edward the Elder, and by 926 Northumbria was under the control of King Æthelstan.

In 937 the combined armies of Olaf Guthfrithson, Viking king of Dublin, Constantine, king of Scotland and Owain ap Dyfnwal, king of the Cumbrians, invaded England. The invading force was met and defeated by an army from Wessex and Mercia led by King Æthelstan at the Battle of Brunanburh. The location of Brunanburh is unknown, but some historians[42][43] have suggested a location between Tinsley in Sheffield and Brinsworth in Rotherham, on the slopes of White Hill.[20] After the death of King Athelstan in 939 Olaf Guthfrithson invaded again and took control of Northumbria and part of Mercia. Subsequently, the Anglo-Saxons, under Edmund, re-conquered the Midlands, as far as Dore, in 942, and captured Northumbria in 944.

The Domesday Book of 1086, which was compiled following the Norman Conquest of 1066, contains the earliest known reference to the districts around Sheffield as the manor of "Hallun" (or Hallam). This manor retained its Saxon lord, Waltheof, for some years after the conquest. The Domesday Book was ordered written by William the Conqueror so that the value of the townships and manors of England could be assessed. The entries in the Domesday Book are written in a Latin shorthand; the extract for this area begins:

- TERRA ROGERII DE BVSLI

- M. hi Hallvn, cu XVI bereuvitis sunt. XXIX. carucate trae

- Ad gld. Ibi hb Walleff com aula...

Translated it reads:

- LANDS OF ROGER DE BUSLI

- In Hallam, one manor with its sixteen hamlets, there are twenty-nine carucates [~14 km2] to be taxed. There Earl Waltheof had an "Aula" [hall or court]. There may have been about twenty ploughs. This land Roger de Busli holds of the Countess Judith. He has himself there two carucates [~1 km2] and thirty-three villeins hold twelve carucates and a half [~6 km2]. There are eight acres [32,000 m2] of meadow, and a pasturable wood, four leuvae in length and four in breadth [~10 km2]. The whole manor is ten leuvae in length and eight broad [207 km2]. In the time of Edward the Confessor it was valued at eight marks of silver [£5.33]; now at forty shillings [£2.00].

- In Attercliffe and Sheffield, two manors, Sweyn had five carucates of land [~2.4 km2] to be taxed. There may have been about three ploughs. This land is said to have been inland, demesne [domain] land of the manor of Hallam.

The reference is to Roger de Busli, tenant-in-chief in Domesday and one of the greatest of the new wave of Norman magnates. Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria had been executed in 1076 for his part in an uprising against William I. He was the last of the Anglo-Saxon earls still remaining in England a full decade after the Norman conquest. His lands had passed to his wife, Judith of Normandy, niece to William the Conqueror. The lands were held on her behalf by Roger de Busli.

The Domesday Book refers to Sheffield twice, first as Escafeld, then later as Scafeld. Sheffield historian S. O. Addy suggests that the second form, pronounced Shaffeld, is the truer form,[32] as the spelling Sefeld is found in a deed issued less than one hundred years after the completion of the survey.[n 5] Addy comments that the E in the first form may have been mistakenly added by the Norman scribe.

Roger de Busli died around the end of the 11th century, and was succeeded by a son, who died without an heir. The manor of Hallamshire passed to William de Lovetot, the grandson of a Norman baron who had come over to England with the Conqueror.[44] William de Lovetot founded the parish churches of St Mary at Handsworth, St Nicholas at High Bradfield and St. Mary's at Ecclesfield at the start of the 12th century in addition to Sheffield's own parish church. He also built the original wooden Sheffield Castle, which stimulated the growth of the town.[15][34]

Also dating from this time is Beauchief Abbey, which was founded by Robert FitzRanulf de Alfreton. The abbey was dedicated to Saint Mary and Saint Thomas Becket, who had been canonised in 1172. Thomas Tanner, writing in 1695, stated that it was founded in 1183.[45] Samuel Pegge in his History of Beauchief Abbey notes that Albinas, the abbot of Derby, who was one of the witnesses to the charter of foundation, died in 1176, placing foundation before that date.[46]

Medieval Sheffield

Following the death of William de Lovetot, the manor of Hallamshire passed to his son Richard de Lovetot and then his son William de Lovetot before being passed by marriage to Gerard de Furnival in about 1204.[47] The de Furnivals held the manor for the next 180 years.[48] The fourth Furnival lord, Thomas de Furnival, supported Simon de Montfort in the Second Barons' War. As a result of this, in 1266 a party of barons, led by John de Eyvill, marching from north Lincolnshire to Derbyshire passed through Sheffield and destroyed the town, burning the church and castle.[34]

A new stone castle was constructed over the next four years and a new church was consecrated by William de Wickwane the Archbishop of York around 1280. In 1295 Thomas de Furnival's son (also Thomas) was the first lord of Hallamshire to be called to Parliament, thus taking the title Lord Furnivall.[49] On 12 November 1296 Edward I granted a charter for a market to be held in Sheffield on Tuesday each week. This was followed on 10 August 1297 by a charter from Lord Furnival establishing Sheffield as a free borough.[50][51]

The Sheffield Town Trust was established in the Charter to the Town of Sheffield, granted in 1297. De Furnival, granted land to the freeholders of Sheffield in return for an annual payment, and a Common Burgery administrated them. The Burgery originally consisted of public meetings of all the freeholders,[52] who elected a Town Collector.[53] Two more generations of Furnivals held Sheffield before it passed by marriage to Sir Thomas Nevil and then, in 1406, to John Talbot, the first Earl of Shrewsbury.[48]

In 1430 the 1280 Sheffield parish church building was pulled down and replaced. Parts of this new church still stand today and it is now Sheffield city centre's oldest surviving building, forming the core of Sheffield Cathedral.[54] Other notable surviving buildings from this period include the Old Queen's Head pub in Pond Hill, which dates from around 1480, with its timber frame still intact, and Bishops' House and Broom Hall, both built around 1500.[55]

Post-medieval Sheffield

The fourth Earl of Shrewsbury, George Talbot took up residence in Sheffield, building the Manor Lodge outside the town in about 1510 and adding a chapel to the Parish Church c1520 to hold the family vault. Memorials to the fourth and sixth Earls of Shrewsbury can still be seen in the church.[56] In 1569 George Talbot, the sixth Earl of Shrewsbury, was given charge of Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary was regarded as a threat by Elizabeth I, and had been held captive since her arrival in England in 1568.[57]

Talbot brought Mary to Sheffield in 1570, and she spent most of the next 14 years imprisoned in Sheffield Castle and its dependent buildings. The castle park extended beyond the present Manor Lane, where the remains of Manor Lodge are to be found. Beside them is the Turret House, an Elizabethan building, which may have been built to accommodate the captive queen. A room, believed to have been the queen's, has an elaborate plaster ceiling and overmantel, with heraldic decorations.[58] During the English Civil War, Sheffield changed hands several times, finally falling to the Parliamentarians, who demolished (slighted) the castle in 1648.

The Industrial Revolution brought large-scale steel making to Sheffield in the 18th century. Much of the medieval town was gradually replaced by a mix of Georgian and Victorian buildings. Large areas of Sheffield's city centre have been rebuilt in recent years, but among the modern buildings, some old buildings have been retained.

Industrial Sheffield

Sheffield developed after the industrial revolution because of its geography.

Fast-flowing rivers, such as the Sheaf, the Don and the Loxley, made it an ideal location for water-powered industries to develop.[59] Raw materials, like coal, iron ore, ganister and millstone grit for grindstones, found in the nearby hills, were used in cutlery and blade production.

As early as the 14th century, Sheffield was noted for the production of knives:

Ay by his belt he baar a long panade,

And of a swerd ful trenchant was the blade.

A joly poppere baar he in his pouche;

Ther was no man, for peril, dorste hym touche.

A Sheffeld thwitel baar he in his hose.

Round was his face, and camus was his nose;

By 1600 Sheffield was the main centre of cutlery production in England outside London, and in 1624 The Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire was formed to oversee the trade.[60] Examples of water-powered blade and cutlery workshops from around this time can be seen at the Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet and Shepherd Wheel museums in Sheffield.

Around a century later, Daniel Defoe in his book A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, wrote:

This town of Sheffield is very populous and large, the streets narrow, and the houses dark and black, occasioned by the continued smoke of the forges, which are always at work: Here they make all sorts of cutlery-ware, but especially that of edged-tools, knives, razors, axes, &. and nails; and here the only mill of the sort, which was in use in England for some time was set up, (viz.) for turning their grindstones, though now 'tis grown more common. Here is a very spacious church, with a very handsome and high spire; and the town is said to have at least as many, if not more people in it than the city of York.[61]

In the 1740s Benjamin Huntsman, a clock maker in Handsworth, invented a form of the crucible steel process for making a better quality of steel than had previously been available.[62] At around the same time Thomas Boulsover invented a technique for fusing a thin sheet of silver onto a copper ingot producing a form of silver plating that became known as Sheffield plate.[63] Originally hand-rolled Old Sheffield Plate was used for making silver buttons. Then in 1751 Joseph Hancock, previously apprenticed to Boulsover's friend Thomas Mitchell, first used it to make kitchen and tableware. This prospered and in 1762–65 Hancock built the water-powered Old Park Silver Mills at the confluence of the Loxley and the Don, one of the earliest factories solely producing an industrial semi-manufacture. Eventually Old Sheffield Plate was supplanted by cheaper electroplate in the 1840s. In 1773 Sheffield was given a silver assay office.[64] In the late 18th century, Britannia metal, a pewter-based alloy similar in appearance to silver, was invented in the town.[65]

Huntsman's process was only made obsolete in 1856 by Henry Bessemer's invention of the Bessemer converter, but production of crucible steel continued until well into the 20th century for special uses, as Bessemer's steel was not of the same quality, in the main replacing wrought iron for such applications as rails.[66] Bessemer had tried to induce steelmakers to take up his improved system, but met with general rebuffs, and finally was driven to undertake the exploitation of the process himself. To this end he erected steelworks in Sheffield.[67] Gradually the scale of production was enlarged until the competition became effective, and steel traders generally became aware that the firm of Henry Bessemer & Co. was underselling them to the extent of £20 a ton. One of Bessemer's converters can still be seen at Sheffield's Kelham Island Museum.

Stainless steel was discovered by Harry Brearley in 1912, at the Brown Firth Laboratories in Sheffield.[68] His successor as manager at Brown Firth, Dr William Hatfield, continued Brealey's work. In 1924 he patented '18-8 stainless steel',[69] which to this day is probably the most common alloy of this type.[70]

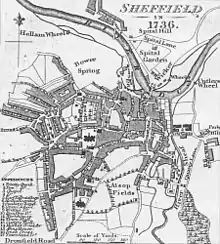

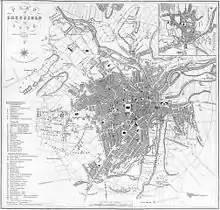

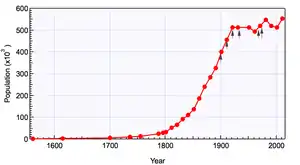

These innovations helped Sheffield to gain a worldwide recognition for the production of cutlery; utensils such as the bowie knife were mass-produced and shipped to the United States. The population of the town increased rapidly. In 1736 Sheffield and its surrounding hamlets held about 7000 people,[71] in 1801 there were 60,000, and by 1901, the population had grown to 451,195.[72]

This growth spurred the reorganisation of the governance of the town. Prior to 1818, the town was run by a mixture of bodies. The Sheffield Town Trust and the Church Burgesses, for example, divided responsibility for the improvement of streets and bridges. By the 19th century both organisations lacked funds and struggled even to maintain existing infrastructure.[52] The Church Burgesses organised a public meeting on 27 May 1805 and proposed to apply to Parliament for an act to pave, light and clean the city's streets. The proposal was defeated.[52]

The idea of a Commission was revived in 1810, and later in the decade Sheffield finally followed the model adopted by several other towns in petitioning for an Act to establish an Improvement Commission. This eventually led to the Sheffield Improvement Act 1818, which established the Commission and included several other provisions.[52] In 1832 the town gained political representation with the formation of a Parliamentary borough. A municipal borough was formed by an Act of Incorporation in 1843, and this borough was granted the style and title of "City" by letters patent in 1893.[73][74]

In 1832 an outbreak of cholera killed 402 people, including John Blake, the Master Cutler. Another 1,000 residents were infected by the disease. A memorial to the victims stands in Clay Wood where the victims of the outbreak are buried.[75]

From the mid-18th century, a succession of public buildings were erected in the town. St Paul's Church, now demolished, was among the first, while the old Town Hall and the present Cutlers' Hall were among the major works of the 19th century. The town's water supply was improved by the Sheffield Waterworks Company, who built reservoirs around the town. Parts of Sheffield were devastated when, following a five-year construction project, the Dale Dyke dam collapsed on Friday 11 March 1864, resulting in the Great Sheffield Flood.

Sheffield's transport infrastructure was also improved.[n 6] In the 18th century turnpike roads were built connecting Sheffield with Barnsley, Buxton, Chesterfield, Glossop, Intake, Penistone, Tickhill, and Worksop.[n 7] In 1774 a 2-mile (3.2 km) wooden tramway was laid at the Duke of Norfolk's Nunnery Colliery. The tramway was destroyed by rioters, who saw it as part of a plan to raise the price of coal.[76] A replacement tramway that used L-shaped rails was laid by John Curr in 1776 and was one of the earliest cast-iron railways.[77] The Sheffield Canal opened in 1819 allowing the large-scale transport of freight.[78]

This was followed by the Sheffield and Rotherham Railway in 1838, the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway in 1845, and the Midland Railway in 1870.[79] The Sheffield Tramway was started in 1873 with the construction of a horse tram route from Lady's Bridge to Attercliffe. This route was later extended to Brightside and Tinsley, and further routes were constructed to Hillsborough, Heeley, and Nether Edge.[80] Due to the narrow medieval roads the tramways were initially banned from the town centre. An improvement scheme was passed in 1875; Pinstone Street and Leopold Street were constructed by 1879, and Fargate was widened in the 1880s. The 1875 plan also called for the widening of the High Street; disputes with property owners delayed this until 1895.[81]

Steel production in the 19th century involved long working hours, in unpleasant conditions that offered little or no safety protection. Friedrich Engels in his The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 described the conditions prevalent in the city at that time:

In Sheffield wages are better, and the external state of the workers also. On the other hand, certain branches of work are to be noticed here, because of their extraordinarily injurious influence upon health. Certain operations require the constant pressure of tools against the chest, and engender consumption in many cases; others, file-cutting among them, retard the general development of the body and produce digestive disorders; bone-cutting for knife handles brings with it headache, biliousness, and among girls, of whom many are employed, anæmia. By far the most unwholesome work is the grinding of knife-blades and forks, which, especially when done with a dry stone, entails certain early death. The unwholesomeness of this work lies in part in the bent posture, in which chest and stomach are cramped; but especially in the quantity of sharp-edged metal dust particles freed in the cutting, which fill the atmosphere, and are necessarily inhaled. The dry grinders' average life is hardly thirty-five years, the wet grinders' rarely exceeds forty-five.[82]

Sheffield became one of the main centres for trade union organisation and agitation in the UK. By the 1860s, the growing conflict between capital and labour provoked the so-called 'Sheffield Outrages', which culminated in a series of explosions and murders carried out by union militants. The Sheffield Trades Council organised a meeting in Sheffield in 1866 at which the United Kingdom Alliance of Organised Trades—a forerunner of the Trades Union Congress (TUC)—was founded.[83]

The 20th century to the present

In 1914 Sheffield became a diocese of the Church of England,[84] and the parish church became a cathedral.[85] During the First World War the Sheffield City Battalion suffered heavy losses at the Somme[86] and Sheffield itself was bombed by a German zeppelin.[87]

The recession of the 1930s was only halted by the increasing tension as the Second World War loomed. The steel factories of Sheffield were set to work making weapons and ammunition for the war. As a result, once war was declared, the city once again became a target for bombing raids. In total there were 16 raids over Sheffield, but it was the heavy bombing over the nights of 12 and 15 December 1940 (now known as the Sheffield Blitz) when the most substantial damage occurred. More than 660 people died and numerous buildings were destroyed.[88]

Following the war, the 1950s and 1960s saw many large scale developments in the city. The Sheffield Tramway was closed, and a new system of roads, including the Inner Ring Road, were laid out. Also at this time many of the old slums were cleared and replaced with housing schemes such as the Park Hill flats,[89] and the Gleadless Valley estate.

In February 1962, the city was devastated by the Great Sheffield Gale. Extremely localised high winds across the city, reaching up to 97 mph (156 km/h), killed four people, injured more than 400, and damaged more than 150,000 houses across the city, leaving thousands homeless.[90]

Sheffield's traditional manufacturing industries (along with those of many other areas in the UK), declined during the 20th century.[91] In the 1980s, it was the setting for two films written by locally-born Barry Hines: Looks and Smiles, a 1981 film that portrayed the depression that the city was enduring, and Threads, a 1984 television film that simulated a nuclear winter in Sheffield after a warhead is dropped to the east of the city.

The building of the Meadowhall shopping centre on the site of a former steelworks in 1990 was a mixed blessing, creating much needed jobs but speeding the decline of the city centre.[92] Attempts to regenerate the city were kick-started by the hosting of the 1991 World Student Games[93] and the associated building of new sporting facilities such as the Sheffield Arena, Don Valley Stadium and the Ponds Forge complex. Sheffield began construction of a tram system in 1992, with the first section opening in 1994.

Starting in 1995, the Heart of the City Project has seen public works in the city centre: the Peace Gardens were renovated in 1998, the Millennium Gallery opened in April 2001, and a 1970s town hall extension was demolished in 2002 to make way for the Winter Garden, which opened on 22 May 2003. A series of other projects grouped under the title Sheffield One aim to regenerate the whole of the city centre.

Sheffield was particularly hard hit during the 2007 United Kingdom floods and the 2010 'Big Freeze'. The 2007 flooding on 25 June caused millions of pounds worth of damage to buildings in the city and led to the loss of two lives.[94] Many landmark buildings such as Meadowhall and the Hillsborough Stadium flooded due to being close to rivers that flow through the city. In 2010, 5,000 properties in Sheffield were identified as still being at risk of flooding. In 2012 the city narrowly escaped another flood, despite extensive work by the Environment Agency to clear local river channels since the 2007 event. In 2014 Sheffield Council's cabinet approved plans to further reduce the possibility of flooding by adopting plans to increase water catchment on tributaries of the River Don.[95][96][97] Another flood hit the city in 2019, resulting in shoppers being contained in Meadowhall Shopping Centre.[98][99]

Between 2014 and 2018, there were disputes between the city council and residents over the fate of the city's 36,000 highway trees. Around 4,000 highway trees have since been felled as part of the ‘Streets Ahead’ Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contract signed in 2012 by the city council, Amey plc and the Department for Transport to maintain the city streets.[100] The tree fellings have resulted in many arrests of residents and other protesters across the city even though most felled trees in the city have been replanted, including those historically felled and not previously replanted.[101] The protests eventually stopped in 2018 after the council paused the tree felling programme as part of a new approach developed by the council for the maintenance of street trees in the city.[102]

In July 2013 the Sevenstone project, which aimed to demolish and rebuild a large part of the city centre, and had been on hold since 2009, was further delayed and the company developing it was dropped.[103] The city council is looking for partners to take a new version of the plan forwards.[104] In April 2014 the council, together with Sheffield University, proposed a plan to reduce the blight of empty shops in the city centre by offering them free of charge to small businesses on a month-by-month basis.[105]

In December 2022, thousands of homes in Hillsborough and Stannington were left without a gas supply for more than a week following a serious failure of the local network. Sheffield City Council declared a major incident as temperatures dropped below freezing in unheated homes, and aid was distributed to local residents.[106]

See also

References

Notes

- For example, an early Roman lamp was found at 354 Walkley Bank Road in 1929.[23]

- Addy 1888, pp. 36–37 suggests two alternative derivations for the name Campo Lane: that it may refer to a field in which football was played, or that it is derived from the Norse kambr meaning a ridge.

- The Roman finds near Stannington and at Bank Street are discussed in Hunter 1819, pp. 15–18.

- In reference to the villages of Wales and Waleswood, Addy 1888, p. 274 states "The Anglo-Saxon invaders or settlers called the old inhabitants or aborigines of this country wealas, or foreigners." Goodall 1913, pp. 292–293 states "these names possess peculiar interest; they refer to the presence of Britons living side by side with the Anglian settlers." See also, "Welsh" in Simpson, J. A.; Weiner, E. S. C., eds. (1989). Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-210019-X.

- The deed is transcribed in Hunter 1819, p. 28.

- See Transport in Sheffield for a more detailed history of Sheffield's transport infrastructure.

- Descriptions of the routes that the turnpike roads followed can be found in Leader, R. E. (1906). The Highways and Byways of Old Sheffield. A lecture delivered before the Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society. (transcription)

References

- Mello, J. Magens (1876). "The Bone Caves of Cresswell Crags". The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 32: 240–244. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1876.032.01-04.31. S2CID 140570446. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Pike, Alistair W.G.; Gilmour, Mabs; Pettitt, Paul; Jacobi, Roger; Ripoll, Sergio; Bahn, Paul; Muñoz, Francisco (2005). "Verification of the age of the Palaeolithic cave art at Creswell Crags, UK". Journal of Archaeological Science. 32 (11): 1649–1655. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.05.002.

- Radley, J.; Mellars, P. (1964). "A Mesolithic structure at Deepcar, Yorkshire, England and the affinities of its associated flint industry". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 30: 1–24. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00015024. S2CID 162212654.

- Sources:

- Tolan-Smith, Chris (2008). "Chap. 5 : Mesolithic Britain". In Bailey, Geoff; Spikins, Penny (eds.). Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–157. ISBN 978-0-521-85503-7.

- Millward, Roy; Robinson, Adrian (1975). The Peak District. Eyre Methuen. p. 97. ISBN 9780413315502.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 312597". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Hey, Gill. "Chapter 5 Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic: Resource Assessment" (PDF). Solent-Thames Research Framework for the Historic Environment. pp. 61–82.

- Historic England. "Cup and ring marked rock 740m east of Park Head House, Sheffield (1018265)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Addy 1888, pp. xliii–lxxiii

- Hey 2010, pp. 6–7

- Bartlett, J. E. (1957). "The excavation of a barrow at Lodge Moor, Sheffield, 1944–55". Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society. 7: 320.

- Historic England. "Carl Wark (312285)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Hey, David (December 2000). "Yorkshire's Southern Boundary". Northern History. XXXVII: 31–47. doi:10.1179/007817200790178120. S2CID 154165051.

- "The Celtic Tribes of Britain: The Brigantes". WWW.Roman-Britain.ORG. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Black, Jeremy (1997). A History of the British Isles. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-333-66282-2.

- Addy 1888, pp. 268–269

- Hunter 1819, chapter 2

- May, Thomas (1922). The Roman Forts of Templebrough Near Rotherham. Rotherham: H. Garnett and Co.

- Leader, R.E. (1906). The Highways and Byways of Old Sheffield. A lecture delivered before the Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society (transcription)

- "Long Causway Management Plan" (PDF). Peak District National Park. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Inglis, D. H. "The Roman Road Project" (PDF). Roman Roads Research Association. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Wood, Michael (2001). "Chapter 11. Tinsley Wood". In Search of England: Journeys into the English Past. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 0-520-23218-6.

- "Roman Britain in 1948: I. Sites Explored". The Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 39: 96–115. 1949. doi:10.2307/297711. JSTOR 297711. S2CID 250348306.

- Addy, Sidney Oldall. The Hall of Waltheof. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017.

- Taylor, M. V.; Collingwood, R. G. (1929). "Roman Britain in 1929: I. Sites Explored: II. Inscriptions". Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 19: 180–218. doi:10.2307/297347. JSTOR 297347. S2CID 161347338.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 314585". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Addy 1888, p. 249

- Walford, Edward; Cox, John Charles; Apperson, George Latimer (1906). "Notes of the Month". The Antiquary. E. Stock. XLII (November): 406. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- "Alan's treasure find sheds light on city's Roman history". Sheffield Star. 13 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Waddington, Clive (2012). "Discovery and Excavation of a Roman Estate Centre at Whirlow, South-west Sheffield" (PDF). Archaeological Research Services. Council for British Archaeology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Hey 2010, p. 9

- Cox, Tony (2003). "The Ancient Kingdom of Elmet". The Barwicker. 39: 43.

- Goodall 1913, pp. 253–254

- Addy 1888, pp. xxviii–xxxiv

- Goodall 1913, p. 138

- Vickers 1999, part 1

- Goodall 1913, pp. 199 & 287

- Historic England. "Monument No. 314520". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- Howarth, E (1907). "Pre-Norman Cross-Shaft at Sheffield". The Reliquary and Illustrated Archæologist. 12: 204–208., but also see Sharpe, Neville T. (2002). Crosses of the Peak District. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Landmark Collector's Library. ISBN 1-84306-044-2.

- "Stone cross shaft". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "The House Of Wessex". English Monarchs. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- "Viking words". British Library. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- Hey 2010, p. 13

- Goodall 1913, pp. 85–86 & 312–313

- Cockburn, John Henry (1931). The battle of Brunanburh and its period elucidated by place-names. London, Sheffield: Sir W. C. Leng & Co., Ltd.

- Hey 2010, p. 15

- Tanner, Thomas (1695). Notitia monastica: A short history of the religious houses in England and Wales.

- Pegge, Samuel (1801). History of Beauchief Abbey.

- Hunter 1819, p. 26

- Hunter 1819, p. 31

- Cokayne, George Edward (1890). Complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, extant, extinct, or dormant. Vol. 3. London: George Bell & Sons. p. 406. ISBN 1-145-31229-2.

- Hunter 1819, pp. 38–39

- Charter to the Town of Sheffield, 10 August 1297

- Binfield, Clyde, ed. (1993). The History of the City of Sheffield, 1843–1993. Volume 1: Politics. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 1-85075-431-4.

- Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1963). The Manor and the Borough. Volume 2. Archon Books. p. 202.

- Harman & Minnis 2004, pp. 45–56

- Harman & Minnis 2004, pp. 4–7

- "Tudor monuments". Sheffield Cathedral. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- Schama, Simon (2000). "The Body of the Queen". A History of Britain I: At the Edge of the World? 3500 B.C.–1603 A.D.. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-48714-3.

- Historic England. "Turret House 150m west of Manor House ruins (1271283)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- Hey, David (2006). "The origins and early growth of the Hallamshire cutlery and allied trades". In John Chartres and David Hey (ed.). English Rural Society, 1500–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 343–368. ISBN 0-521-03156-7. OCLC 173078495.

- Binfield & Hey 1997, pp. 26–39

- Defoe, Daniel (1723–27). "Letter 8, Part 3: South and West Yorkshire". A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain. London: G. Strahan. (transcription)

- Tweedale, Geoffrey (1986). "Metallurgy and Technological Change: A Case Study of Sheffield Specialty Steel and America, 1830–1930". Technology and Culture. The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the Society for the History of Technology. 27 (2): 189–222. doi:10.2307/3105143. JSTOR 3105143. S2CID 112532430.

- "Boulsover, Thomas (1705–1788)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53918. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Binfield & Hey 1997, p. 185

- Taylor, John, ed. (1879). The Illustrated Guide to Sheffield and the Surrounding District. Sheffield: Pawson and Brailsford. p. 288.

- Barraclough KC, Steel before Bessemer 2 volumes London 1984

- Carnegie, David; Gladwyn, Sidney C. (1913). "Chapter XIV: The Evolution of the Bessemer Converter". Liquid Steel: Its Manufacture and Cost. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- "Harry Brearley 1871–1948". Tilt Hammer. Archived from the original on 21 November 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Desch, C. H. (1944). "William Herbert Hatfield". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. London: The Royal Society. 4 (13): 617–627. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1944.0012. JSTOR 768852. S2CID 161490802.

- "Steel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago. 2008.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thomas, John (1830). Local Register and chronological account of occurrences and facts connected with the town and neighbourhood of Sheffield. Sheffield: Robert Leader. p. xi.

- United Kingdom Census data. See, "Sheffield District: Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- "History of the Lord Mayor". Sheffield City Council website. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2005.

- "No. 26374". The London Gazette. 21 February 1893. p. 944.

- Historic England. "Cholera Monument (1246737)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Leader, Robert Eadon (1901). Sheffield in the Eighteenth Century. Sheffield: Sheffield Independent Press. pp. 84 & 341.

- Ritchie, Robert (1846). Railways; Their Rise, Progress, and Construction. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 18.

- Vickers 1999, p. 17

- Batty, S. (1984). Rail Centres: Sheffield. Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan Limited. ISBN 1-901945-21-9.

- Twidale, Graham H. E. (1995). A Nostalgic Look At Sheffield Trams Since 1950. Peterborough: Silver Link Publishing, Limited. p. 2. ISBN 1-85794-040-7.

- Olive, Martin (1994). Images of England: Central Sheffield. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited. p. 9. ISBN 0-7524-0011-8.

- Engels, Friedrich (1844). The Condition of the Working Class in England. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. ISBN 1-4346-0825-5.

- "Events that led to the first TUC". TUC website. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- "Homepage of the Anglican Diocese of Sheffield". Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- "History". Sheffield Cathedral website. Archived from the original on 13 October 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- "The Sheffield City Battalion: 12th (Service) Battalion, York & Lancaster Regiment". Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Vickers 1999, p. 20

- Taylor, Evans & Fraser 1996, p. 321

- Vickers 1999, p. 21

- Eden, Philip. "THE SHEFFIELD GALE OF 1962" (PDF). Royal Meteorological Society. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Lambert, Tim. "A Brief History of Sheffield". Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- Taylor, Evans & Fraser 1996, pp. 144–147

- "FISU History". International University Sports Federation. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- "Two die in Sheffield flood chaos". BBC News Online. BBC. 25 June 2007. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- "£55m flood scheme plans backed". BBC News. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- "Foreword | Protecting Sheffield from Flooding". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019.

- "River Don Catchment Flood Management Plan" (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. December 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- "Sheffield flooding: Torrential rain leaves city flooded". BBC News. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- Gillett, Francesca (8 November 2019). "UK flooding: Dozens spend night in Sheffield Meadowhall shopping centre". BBC News. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- Kirby, Dean (17 October 2015). "Sheffield residents are involved bitter row with the council over tree-felling". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "New trees take root on Sheffield highways". Sheffield News Room. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- correspondent, Josh Halliday North of England (26 March 2018). "Sheffield council pauses tree-felling scheme after criticism". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- Marsden, Richard (29 July 2013). "'Vital need' for Sheffield city centre redevelopment". Sheffield Star. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Sheffield plans new retail scheme after Sevenstone scrapped". BBC News. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "Bid to revitalise empty shops in city centre". Sheffield Telegraph. 12 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "Stannington: Major incident declared as homes still without gas". BBC News. BBC. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

Further reading

- Addy, Sidney Oldall (1888). A Glossary of Words Used in the Neighbourhood of Sheffield. Including a Selection of Local Names, and Some Notices of Folk-Lore, Games, and Customs. London: Trubner & Co. for the English Dialect Society.

- Armytage, W. H. G. "Sheffield and the Crimean War: Politics and Industry 1852-1857." History Today (July 1955), 5#7 pp 473–482.

- Askew, Rachel (2017). "Sheffield Castle and The Aftermath of The English Civil War". Northern History. 54 (2): 189–210. doi:10.1080/0078172X.2017.1337313. S2CID 159550072.

- Binfield, Clyde; Hey, David (1997). Mesters to Masters: A History of the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-828997-9.

- Goodall, Armitage C. (1913). Place-Names of South-West Yorkshire; that is, of so much of the West Riding as lies south of the Aire from Keighley onwards. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harman, R.; Minnis, J. (2004). Pevsner City Guides: Sheffield. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10585-1.

- Hey, David (2010). A History of Sheffield (3rd ed.). Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85936-198-6.

- Hunter, Joseph (1819). Hallamshire. The History and Topography of the Parish of Sheffield in the County of York. London: Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mayor & Jones. (wikisource)

- Moreland, John; Hadley, Dawn; Tuck, Ashley; Rajic, Milica (2020). Sheffield Castle: archaeology, archives, regeneration, 1927–2018. Heslington: White Rose University Press. doi:10.22599/SheffieldCastle. ISBN 9781912482290.

- Taylor, Ian R.; Evans, Karen; Fraser, Penny (1996). A Tale of Two Cities: Global change, local feeling, and everyday life in the North of England. A study in Manchester and Sheffield. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13829-9.

- Vickers, J. Edward MBE (1999). Old Sheffield Town. An Historical Miscellany (2nd ed.). Sheffield: The Hallamshire Press Limited. ISBN 1-874718-44-X.