Slighting

Slighting is the deliberate damage of high-status buildings to reduce their value as military, administrative or social structures. This destruction of property sometimes extended to the contents of buildings and the surrounding landscape. It is a phenomenon with complex motivations and was often used as a tool of control. Slighting spanned cultures and periods, with especially well-known examples from the English Civil War in the 17th century.

Meaning and use

Slighting is the act of deliberately damaging a high-status building, especially a castle or fortification, which could include its contents and the surrounding area.[3] The first recorded use of the word 'slighting' to mean a form of destruction was in 1613.[4] Castles are complex structures combining military, social, and administrative uses,[5] and the decision to slight them took these various roles into account. The purpose of slighting was to reduce the value of the building, whether military, social, or administrative.[3] Destruction often went beyond what was needed to prevent an enemy from using the fortification, indicating the damage was important symbolically.[6] When Eccleshall Castle in Staffordshire was slighted as a result of the English Civil War, the act was politically motivated.[7]

In some cases it was used as a way of punishing the king's rebels, or was used to undermine the authority of the owner by demonstrating his inability to protect his property.[8] As part of the peace negotiations bringing The Anarchy of 1135–1154 to an end, both sides agreed to dismantle fortifications built since the start of the conflict.[9] Similarly, in 1317 Edward II ordered the dismantling of Harbottle Castle in Northumberland in England as part of a treaty with Robert the Bruce.[10]

In England, Scotland, and Wales, it was uncommon for someone to slight his own fortifications but not unknown; during the First War of Scottish Independence, Robert the Bruce systematically slighted Scottish castles, often after capturing them from English control.[11][12] More than a century earlier, John, King of England, ordered the demolition of Château de Montrésor in France, during his war with the French king over control of Normandy.[13] In the Levant, Muslim rulers adopted a policy of slighting castles and fortified towns and cities to deny them to Crusaders; the Sultan Baybars, for example, instigated the destruction of fortifications at Jaffa in 1267, Antioch in 1268, and Askelon in 1270.[14]

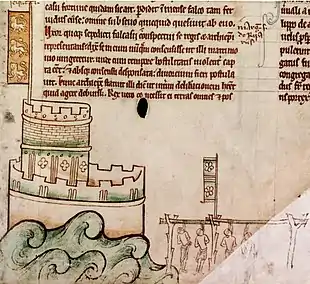

Methods of destruction

.jpg.webp)

Castles were demolished with a range of methods, each affecting the buildings in different ways. Fire might be used, especially against timber structures; digging underneath stone structures (known as undermining) could cause them to collapse; dismantling a structure by hand was sometimes done, but was time- and labour-intensive, as was filling ditches and digging away earthworks; and in later periods gunpowder was sometimes used.[16][17] Manually dismantling a castle ("picking") can be split into two categories: primary damage where the intention was to slight the castle; and secondary damage which was incidental through activity such as retrieving reusable materials.[18]

Undermining involved digging underneath a wall or removing stones at its base. When successful, the tunnel or cavity would collapse, making it difficult to identify through archaeology. Archaeological investigations have identified 61 castles that were slighted in the Middle Ages, and only five were undermined.[19] While surviving mines are rare, one was discovered in the 1930s during excavations at Bungay Castle in Suffolk. It probably dates from around 1174 when the owner rebelled against Henry II.[20]

The effect of slighting

Dismantling a castle was a skilled process, and stone, metal, and glass were sometimes removed for sale or reuse.[23] After the castle at Papowo Biskupie in Poland was slighted, some of the materials from the castle were used to build a seminary at nearby Chełmża.[24]

The impact of slighting ranged from almost complete destruction of a site, as can be seen at Deganwy Castle, to a token gesture,[25] for example damaging elements such as arrowslits.[26] In 1268, the court of King Louis IX of France gave orders to slight a new fortification near Étampes, specifying that the bailiff carrying out orders should "destroy the arrow-slits and so to break them through that it may be abundantly clear that the fortification has been slighted".[27]

Destruction was often carefully targeted rather than indiscriminate, even when carried out on a large scale. In cases of medieval slighting, domestic areas such as free-standing halls and chapels were typically excluded from the destruction.[28]

When King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland gave the order to slight the castle at Mała Nieszawka, after negotiation with the Teutonic Order who owned the castle, one of the conditions was that the buildings in the outer bailey would be left intact while the walls were reduced in height.[29] In 1648, Parliament gave orders to slight Bolsover Castle but that "so much only be done to it as to make it untenable as a garrison and that it may not be unnecessarily spoiled and defaced."[30] When a castle had a keep, it was usually the most visible part of the castle and a focus of symbolism.[31] This would sometimes attract the attention of people carrying out slighting. Kenilworth was one of many castles to be slighted during the English Civil War, and the side of the keep most visible to people outside the castle was demolished.[32]

Documentary sources for the medieval period typically have little information on what slighting involved, so archaeology helps to understand which areas of buildings were targeted and how they were demolished.[33][34] For the English Civil War, destruction accounts are rare but there are some instances such as Sheffield Castle where detailed records survive. At Sheffield military and social concerns combined: there may have been a desire to prevent the Royalist owner from using the fortification against Parliament, and the destruction undermined the owner's authority. Despite this, the profits from the demolition went to the owner, contrasting with Pontefract Castle, where the money went to the townspeople.[35]

When castles were slighted in the Middle Ages this often led to their complete abandonment, but some were repaired and others reused.[36] This was also the case with places slighted as a result of the English Civil War. In 1650, Parliament gave orders to slight Wressle Castle; the south part of the castle was left standing so that the owner could still use it as a manor house.[37] Berkeley Castle was also slighted in the same period – meaning that a small but significant part of the curtain wall was demolished, but the remaining structure was left intact, and the castle remains inhabited to this day.

The use of destruction both to control and to subvert control spans periods and cultures. Slighting was prevalent in the Middle Ages and the 17th century; notable episodes include The Anarchy, the English Civil War, and France in the 16th and 17th centuries, as well as Japan.[38][39][40] The ruins left by the destruction of castles in 17th-century England and Wales encouraged the later Romantic movement.[41]

See also

- Iconoclasm – Destruction of religious images

- List of destroyed heritage – Destroyed Heritage

- Vitrified fort – Stone enclosure with vitrified walls

Notes

- Thompson 1987, pp. 179–185.

- Steane 1999.

- Nevell 2019, p. 101.

- Simpson & Weiner 1989, p. 704.

- Johnson 2002, pp. 178–179.

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 112.

- Askew 2016, p. 284.

- Nevell 2019, pp. 26–28.

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 111.

- Hunter-Blair 1949, p. 145.

- Nevell 2019, p. 111.

- Cornell 2008, pp. 249–250.

- Powicke 1999, p. 160.

- Möhring 2009, p. 216.

- Rakoczy 2007, pp. 67–68.

- Rakoczy 2007, p. 60.

- Nevell 2019, pp. 6–11.

- Rakoczy 2007, pp. 94–98.

- Nevell 2019, pp. 21–22.

- Braun 1934, p. 118.

- Amt 2002, p. 114.

- Baker et al. 1979, p. 11.

- Rakoczy 2008, pp. 282–283.

- Szczupak 2021, p. 9.

- Nevell 2019, p. 102.

- Liddiard 2005, p. 68.

- Coulson 1973, pp. 64–65.

- Nevell 2019, p. 124.

- Szczupak 2021, p. 6.

- Thompson 1987, p. 152.

- Marshall 2016.

- Johnson 2002, p. 174.

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 114.

- Nevell 2019.

- Askew 2017, pp. 203–204.

- Nevell 2019, p. 126.

- Richardson & Dennison 2015, p. 12.

- Johnson 2002, p. 173.

- Rakoczy 2007, p. 11.

- Nevell 2019, p. 120.

- Thompson 1987, p. 157.

Bibliography

- Amt, Emilie (2002). "Besieging Bedford". Besieging Bedford: Military Logistics in 1224. pp. 101–124. ISBN 9780851159096. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt7zssh1.9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Askew, Rachel (2016), "Political iconoclasm: the destruction of Eccleshall Castle during the English Civil Wars", Post-Medieval Archaeology, 50 (2): 279–288, doi:10.1080/00794236.2016.1203547, S2CID 157307448

- Askew, Rachel (2017), "Sheffield Castle and The Aftermath of The English Civil War", Northern History, 52 (2): 189–210, doi:10.1080/0078172X.2017.1337313, S2CID 159550072

- Baker, David; Baker, Evelyn; Hassall, Jane; Simco, Angela (1979), "The Excavations: Bedford Castle" (PDF), Bedford Archaeology, 13: 7–64

- Braun, Hugh (1934), "Some notes on Bungay Castle" (PDF), Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, 22: 109–119

- Cornell, David (2008), "A Kingdom Cleared of Castles: the Role of the Castle in the Campaigns of Robert Bruce", The Scottish Historical Review, 87 (224): 233–257, doi:10.3366/E0036924108000140, JSTOR 23074055, S2CID 153554882

- Coulson, Charles (1973), "Rendability and Castellation in Medieval France", Château Gaillard: Études de castellologie médiévale, 6: 59–67

- Creighton, Oliver; Wright, Duncan (2017), The Anarchy: War and Status in 12th-Century Landscapes of Conflict, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-1-78138-242-4

- Hunter-Blair, C. H. (1949), "Knights of Northumberland in 1278 and 1324", Archaeology Aeliana, 27: 122–176

- Johnson, Matthew (2002), Behind the Castle Gate: From Medieval to Renaissance, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-25887-1

- Liddiard, Robert (2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield: Windgather Press, ISBN 9780954557522

- Marshall, Pamela (2016), "Some Thoughts on the Use of the Anglo-Norman Donjon", in Davies, John A.; Riley, Angela; Levesque, Jean-Marie; Lapiche, Charlotte (eds.), Castles and the Anglo-Norman World, Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 159–174

- Möhring, Hannes (2009). "Die muslimische Strategie der Schleifung fränkischen Festungen und Städte in der Levante". Burgen und Schlösser: Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). 50 (4): 211–217. doi:10.11588/bus.2009.4.48565.

- Nevell, Richard (2019), "The archaeology of slighting: a methodological framework for interpreting castle destruction in the Middle Ages", The Archaeological Journal, 177 (1): 99–139, doi:10.1080/00665983.2019.1590029, S2CID 182653612

- Powicke, F. M. (1999) [1913], The Loss of Normandy, 1198–1204, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-5740-3

- Rakoczy, Lila (2007). Archaeology of Destruction: A Reinterpretation of Castle Slightings in the English Civil War (PhD). University of York. OCLC 931130655.

- Rakoczy, Lila (2008), "Out of the Ashes: Destruction, Reuse, and Profiteering in the English Civil War", in Rakoczy, Lila (ed.), The Archaeology of Destruction, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84718-624-9

- Richardson, Shaun; Dennison, Ed (2015), Garden and Other Earthworks, South of Wressle Castle, Wressle, East Yorkshire: Archaeological Survey (PDF), Ed Dennison Archaeological Services and the Castle Studies Trust

- Szczupak, Dominika (2021). "Techniki rozbiórki krzyżackich obiektów warownych w średniowieczu (Potterberg, Nieszawa, Toruń, Papowo Biskupie)". Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej (in Polish). 69 (1): 3–18. doi:10.23858/KHKM69.2021.1.001. S2CID 238793518.

- Simpson, J. A.; Weiner, E. S. C. (1989), The Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition. Volume XV Ser–Soosy, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Steane, John (1999), The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy, London: Routledge

- Thompson, M. W. (1987), The Decline of the Castle, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521083973

Further reading

- Jóźwiak, Sławomir (2003). "Zburzenie zamku komturskiego w Nieszawie w latach 1422–1423" (PDF). Rocznik Toruński (in Polish). 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2023.

- Nevell, Richard (2017). The Archaeology of Castle Slighting in the Middle Ages (PhD). University of Exeter. hdl:10871/33181.

- Nevell, Richard (2020). "Slighting". In Smith, Claire (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3497-1. S2CID 243069467.

- Rakoczy, Lila (2007a). "Breaking down Walls: Cross-disciplinary approaches to castle destruction". In Schroeder, H.; Bray, P.; Gardner, P.; Jefferson, V.; Macaulay-Lewis, E. (eds.). Crossing frontiers: the opportunities and challenges of interdisciplinary approaches to archaeology: proceedings of a conference held at the University of Oxford, 25–26 June 2005. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 45–54. ISBN 9780954962777.