History of Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire is a county that is situated in the East Midlands of England. The county has history within the Palaeolithic period, dating anywhere between 500,000 and 10,000 BCE,[1] as well as early Anglo-Saxon communities, dating to 600 CE.[2] Furthermore, the county has significance in the political aspects of English history, particularly within intercommunal fighting, and its economics is historically centred around coal and textiles.

Chronology

English control

The earliest Teutonic settlers in the district which is now Nottinghamshire were an Anglian tribe who, not later than the 5th century, advanced from Lincolnshire along the Fosseway, and, pushing their way up the Trent valley, settled in the fertile districts of the south and east, the whole region from Nottingham to within a short distance of Southwell being then occupied by the vast forest of Sherwood.[3]

At the end of the 6th century Nottinghamshire already existed as organised territory, though its western limit probably extended no farther than the Saxon relics discovered at Oxton and Tuxford. Nottingham, after the treaty of Wedmore, became one of the five Danish boroughs. On the break-up of Mercia under Hardicanute, Nottinghamshire was included in the earldom of the Middle English, but in 1049 it again became part of Leofric's earldom of Mercia, and descended to Edwin and Morkere.[3]

Land division

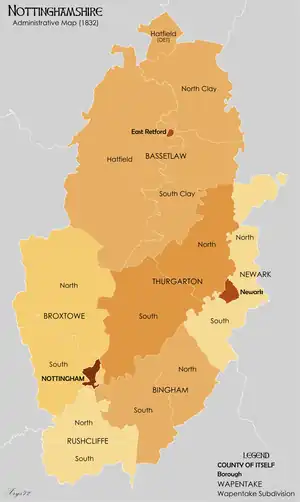

The first mention of the shire of Nottingham occurs in 1016, when it was harried by Canute. The boundaries have remained practically unaltered since the time of the Domesday Survey from 1086, and the eight Domesday wapentakes were unchanged in 1610; in 1719 they had been reduced to six, their present number, Oswaldbeck being absorbed in Bassetlaw, of which it forms the North Clay division, and Lythe in Thurgarton.[3]

Nottinghamshire was originally included in the diocese and province of York, and in 1291 formed an archdeaconry, comprising the deaneries of Nottingham, Newark, Bingham and Retford. By act of Parliament of 1836 the county was transferred to the diocese of Lincoln and province of Canterbury, with the additional deanery of Southwell.[3]

In 1878, the deaneries of Mansfield, South Bingham, West Bingham, Collingham, Tuxford and Worksop were created, and in 1884 most of the county was transferred to the newly created diocese of Southwell, the deaneries being unchanged. The deaneries of Bawtry, Bulwell, Gedling, East Newark and Norwell were created in 1888.[3]

Political history

The most interesting historic figure in the Domesday survey of Nottinghamshire is William Peverel (1040 – c. 1115). His fief represents the honour of Nottingham, and in 1068 he was appointed constable of the castle which William the Conqueror had raised at Nottingham. The Cliftons of Clifton and the Byrons of Newstead held lands in Nottinghamshire at the time of the Survey. Holme Pierrepoint belonged to the Pierrepoints from the time of Edward L; Shelford was the seat of the Stanhopes, and Langar of the Tibetots, afterwards earls of Worcester. Archbishop Cranmer was a descendant of the Cranmers of Aslockton near Bingliam.[3]

The political history of Nottinghamshire centres round the town and castle of Nottingham, which was seized by Robert of Gloucester on behalf of Maud in 1140; captured by John in 1191; surrendered to Henry III by the rebellious barons in 1264; formed an important station of Edward III in the Scottish wars; and in 1397 was the scene of a council where three of the lords appellant were appealed of treason. In the Wars of the Roses the county as a whole favoured the Yorkist cause, Nottingham being one of the most useful stations of Edward IV. In the Civil War of the 17th century most of the nobility and gentry favoured the Royalist cause, but Nottingham Castle was garrisoned for the parliament, and in 1651 was ordered to be demolished.[3]

From 1295, the county and town of Nottingham each returned two members to parliament. In 1572 East Retford was represented by two members, and in 1672 Newark-upon-Trent also. Under the Reform Act of 1832 the county returned four members in two divisions. By the act of 1885 it returned four members in four divisions; Newark and East Retford were disfranchised, and Nottingham returned three members in three divisions.[3]

Until 1568, Nottinghamshire was united with Derbyshire under one sheriff, the courts and tourns being held at Nottingham until the reign of Henry III, when with the assizes for both counties they were removed to Derby. In the time of Edward I the assizes were again held at Nottingham, where they are held at the present day. The Peverel Court, founded before 1113 for the recovery of small debts, had jurisdiction over 127 towns in Nottinghamshire, and was held at Nottingham until 1321, in 1330 at Algarthorpe and in 1790 at Lenton, being finally abolished in 1849.[3]

Economy

Among the earliest industries of Nottinghamshire were the malting and woollen industries, which flourished in Norman times. The latter declined in the 16th century, and was superseded by the hosiery manufacture which sprang up after the invention of the stocking-loom in 1589.[3]

The earliest evidence of the working of the Nottinghamshire coalfield is in 1259, when Queen Eleanor was unable to remain in this county on account of the smoke of the sea-coal. Collieries are scarcely heard of in Nottinghamshire in the 17th century, but in 1620 the justices of the peace for the shire report that there is no fear of scarcity of grain, as the counties which send up the Trent for coal bring grain in exchange, and in 1881 thirty-nine collieries were at work in the county. Hops were formerly extensively grown, and Worksop was famous for its liquorice. Numerous cotton mills were erected in Nottinghamshire in the 18th century, and there were silk-mills at Nottingham. The manufacture of tambour lace existed in Nottinghamshire in the 18th century, and was facilitated in the 19th century by the manufacture of machine-made net.[3]

Relics

At the dissolution of the monasteries there were no fewer than forty religious houses in Nottinghamshire. The only important monastic remains, however, are those at Newstead, but the building is partly transformed into a mansion which was formerly the residence of Lord Byron. There are also traces of monastic ruins at Beauvale, Mattersey, Radford and Thurgarton.[3]

The finest parish church in the county is that of Newark. The churches of St Mary, Nottingham, and of Southwell were collegiate churches; Southwell, now a cathedral, is a splendid building, principally Norman. The churches of Balderton, Bawtry, Hoveringham, Mansfield and Worksop are also partly Norman, and those of Coddington, Hawton and Upton St Peter near Southwell, Early English. Of the old castles, the principal remains are those at Newark, but there are several interesting old mansions, as at Kingshaugh, Scrooby, Shelford and Southwell. Wollaton Hall, near Nottingham, is a fine old building (c. 1580). The finest residences of more modern date are Welbeck and others in the Dukeries.[3]

References

- V., Beckett, J. (1997). A Centenary history of Nottingham. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4001-9. OCLC 35033526.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gurnham, Richard (2010). A History of Nottingham. Phillimore & Company. ISBN 978-1860776588.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 828.

- David Roffe (University of Sheffield): Nottingham and the Shire, Nottinghamshire and the North: a Domesday Study, 1987 and 2002

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nottinghamshire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 827–828.

Further reading

- Amos, David. "The Nottinghamshire miners, the Union of Democratic Mineworkers and the 1984-85 miners strike: scabs or scapegoats?' (PhD Diss. University of Nottingham, 2012). online

- Brook, Michael. A Nottinghamshire Bibliography: Publications on Nottinghamshire History Before 1998 (Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, 2002). online

- Chambers, Jonathan David. Nottinghamshire in the Eighteenth Century: a Study of Life and Labour under the Squirearchy (Routledge, 1966).

- Dockerill, R. P. "Local Government Reform, Urban Expansion and Identity: Nottingham and Derby, 1945-1968" (PhD. Diss. University of Leicester, 2013) online.

- Griffin, Alan Ramsay. The Miners of Nottinghamshire, 1914-1944: A History of the Nottingham Miners' Unions (Allen & Unwin, 1962).

- Murfet, George J. "Nottingham and the Leen Valley: bleaching and dyeing in a historical context." Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists 107.10 (1991): 348–356.

- Wood, Alfred Cecil. A history of Nottinghamshire (SR Publishers, 1947).

- Wood, Alfred Cecil. Nottinghamshire in the Civil War (SR Publishers, 1971).

Older books

- Brown, Cornelius. A history of Nottinghamshire (E. Stock, 1891) online.

- White, Francis. Nottinghamshire: History, Gazetteer, and Directory of the County (1864).

- Throsby, John. Thoroton’s History of Nottinghamshire, 1677, Republished with large additions by John Throsby, 3 volumes (1790, 1796)

- Samuel Tymms (1835). "Nottinghamshire". Midland Circuit. The Family Topographer: Being a Compendious Account of the ... Counties of England. Vol. 5. London: J.B. Nichols and Son. OCLC 2127940.

External links

- Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway essays on local history by experts; covers places, people, themes and events.

- "Nottinghamshire", Historical Directories, UK: University of Leicester