History of San Francisco

The history of the city of San Francisco, California, and its development as a center of maritime trade, were shaped by its location at the entrance to a large natural harbor. San Francisco is the name of both the city and the county; the two share the same boundaries. Only lightly settled by European-Americans at first, after becoming the base for the gold rush of 1849 the city quickly became the largest and most important population, commercial, naval, and financial center in the American West. San Francisco was devastated by a great earthquake and fire in 1906 but was quickly rebuilt. The San Francisco Federal Reserve Branch opened in 1914, and the city continued to develop as a major business city throughout the first half of the 20th century. Starting in the later half of the 1960s, San Francisco became the city most famous for the hippie movement. In recent decades, San Francisco has become an important center of finance and technology. The high demand for housing, driven by its proximity to Silicon Valley, and the limited availability has led to the city being one of America's most expensive places to live. San Francisco is currently ranked 16th on the Global Financial Centres Index.[1]

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

Early history

The earliest evidence of human habitation in what is now the city of San Francisco dates to 3000 BC. Native Americans who settled in this region found the bay to be a resource for hunting and gathering, leading to the establishment of many small villages. Collectively, these early Native Americans are now known as the Ohlone, and the language they spoke belonged to the Miwok family. Their trade patterns included places as far away as Baja California, the Mojave Desert and Yosemite.[2]

The earliest Europeans to reach the site of San Francisco were a Spanish exploratory party in 1769, led overland from Mexico by Don Gaspar de Portolá and Fra. Joan Crespí. The Spanish recognized the location, with its large natural harbor, to be of great strategic significance. A subsequent expedition, led by Juan Bautista de Anza, selected sites for military and religious settlements in 1774. The Presidio of San Francisco was established for the military, while Mission San Francisco de Asís began the cultural and religious conversion of some 10,000 Ohlone who lived in the area.[3] The mission became known as Mission Dolores, because of its nearness to a creek named after Our Lady of Sorrows.

The first anchorage was established at a small inlet on the north-east end of the peninsula (later filled: now lower Market Street), and the small settlement that grew up nearby was named Yerba Buena, after the herb of the same name that grew in abundance there. The original plaza of the Spanish settlement remains as Portsmouth Square. Today's city took its name from the mission, and Yerba Buena became the name of a San Francisco neighborhood now known as South of Market. The Moscone Center and Yerba Buena Gardens are in the Yerba Buena area. In addition, the name Yerba Buena was applied to the former Goat Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, adjacent to Treasure Island.

San Francisco became part of the United States with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Precolonial history

European visitors to the San Francisco Bay Area were preceded at least 8,000 years earlier by Native Americans. According to one anthropologist, the indigenous name for San Francisco was Ahwaste, meaning, "place at the bay".[4] Linguistic and paleontological evidence is unclear as to whether the earliest inhabitants of the area now known as San Francisco were the ancestors of the Ohlone population encountered by the Spanish in the late 18th century.[5] The cultural unit, Ohlone, to which the San Francisco natives belonged did not recognize the city or county boundaries imposed later by Americans, and were part of a contiguous set of bands that lived from south of the Golden Gate to San José.[5]

When the Spanish arrived, they found the area inhabited by the Yelamu tribe, which belongs to a linguistic grouping later called the Ohlone. The Ohlone speakers are distinct from Pomo speakers north of the San Francisco Bay, and are part of the Miwok group of languages. Their traditional territory stretched from Big Sur to the San Francisco Bay, although their trading area was much larger. Miwok-speaking Indians also lived in Yosemite, and Ohlone-speakers intermarried with Chumash and Pomo speakers as well.[5]

The Spanish conquest of the San Francisco Bay area came later than to Southern California. San Francisco's characteristic foggy weather and geography led early European explorers such as Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo to bypass the Golden Gate and miss entering San Francisco Bay, although it seems clear from historical accounts of navigation that they passed close to the coastline north and south of the Golden Gate.[6]

Arrival of Europeans and early settlement

A Spanish exploration party, led by Portolá and arriving on November 2, 1769, was the first documented European sighting of San Francisco Bay. Portolá claimed the area for Spain as part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.[7] Seven years later a Spanish mission, Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores), was established by Fra. Junípero Serra, and a military fort was built, the Presidio of San Francisco.[8][9]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

In 1786 French explorer, the Comte de La Pérouse visited San Francisco and left a detailed account of it.[8] Six years later, in 1792 British explorer George Vancouver also stopped in San Francisco, in part, according to his journal, to spy on the Spanish settlements in the area.[10] In addition to Western Europeans, Russian fur-traders also visited the area. From 1770 until about 1841, Russian traders colonized an area that ranged from Alaska south to Fort Ross in Sonoma County, California. The naming of San Francisco's Russian Hill neighborhood is attributed to the remains of Russian fur traders and sailors found there.

Upon independence from Spain in 1821, the area became part of Mexico. In 1835, Englishman William Richardson erected the first significant homestead outside the immediate vicinity of the Mission Dolores,[11] near a boat anchorage around what is today Portsmouth Square. Together with Alcalde Francisco de Haro, he laid out a street plan for the expanded settlement, and the town, named Yerba Buena after the herb, which was named by the missionaries that found it abundant nearby, began to attract American settlers. In 1838, Richardson petitioned and received a large land grant in Marin County and, in 1841, he moved there to take up residence at Rancho Sauselito. Richardson Bay to the north bears his name.

The British Empire briefly entertained the idea of purchasing the bay from Mexico in 1841, claiming it would "Secure to Great Britain all the advantages of the finest port in the Pacific for her commercial speculations in time of peace, and in war for more easily securing her maritime ascendency". However little came of this, and San Francisco would become a prize of the United States rather than that of British naval power.[12]

On July 31, 1846, Yerba Buena doubled in population when about 240 Mormon pioneers from the East coast arrived on the ship Brooklyn, led by Sam Brannan. Brannan, also a member of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, would later become well known for being the first publicist of the California Gold Rush of 1849 and the first millionaire resulting from it.

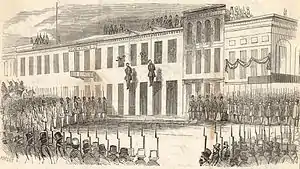

US Navy Commodore John D. Sloat claimed California for the United States on July 7, 1846, during the Mexican–American War, and US Navy Captain John Berrien Montgomery and US Marine Second Lieutenant Henry Bulls Watson of the USS Portsmouth arrived to claim Yerba Buena two days later by raising the flag over the town plaza, which is now Portsmouth Square in honor of the ship. Henry Bulls Watson was placed in command of the garrison there. In August 1846, Lt. Washington A. Bartlett was named alcalde of Yerba Buena. On January 30, 1847, Lt. Bartlett's proclamation changing the name Yerba Buena to San Francisco took effect.[13][14] The city and the rest of California officially became American in 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican–American War. California was admitted to the U.S. as a state on September 9, 1850—the State of California soon chartered San Francisco and San Francisco County. At the time the county and city were not coterminous; the county contained modern-day northern San Mateo County.

Situated at the tip of a windswept peninsula without water or firewood, San Francisco lacked most of the basic facilities for a 19th-century settlement. These natural disadvantages forced the town's residents to bring water, fuel and food to the site. The first of many environmental transformations was the city's reliance on filled marshlands for real estate. Much of the present downtown is built over the former Yerba Buena Cove, granted to the city by military governor Stephen Watts Kearny in 1847.

1848 gold rush

The California gold rush starting in 1848 led to a large boom in population, including considerable immigration. Between January 1848 and December 1849, the population of San Francisco increased from 1,000 to 25,000. The rapid growth continued through the 1850s and under the influence of the 1859 Comstock Lode silver discovery. This rapid growth complicated city planning efforts, leaving a legacy of narrow streets that continues to characterize the city to this day.

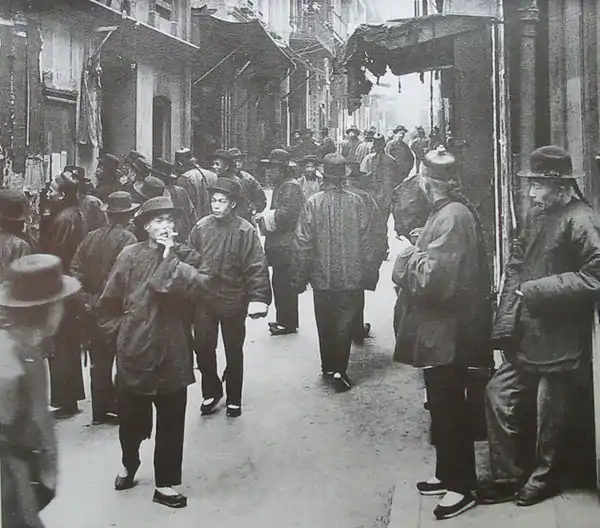

The population boom included many workers from China who came to work in the gold mines and later on the Transcontinental Railroad. The Chinatown district of the city became and is still one of the largest in the country; today, as a result of that legacy, the city as a whole is roughly one-fifth Chinese, one of the largest concentrations outside of China. Many businesses founded to service the growing population exist today, notably Levi Strauss & Co. clothing, Ghirardelli chocolate, and Wells Fargo bank. Many famous railroad, banking, and mining tycoons or "robber barons" such as Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis P. Huntington, and Leland Stanford settled in the city in its Nob Hill neighborhood. The sites of their mansions are now famous and expensive San Francisco hotels (Mark Hopkins Hotel and the Huntington Hotel).

As in many mining towns, the social climate in early San Francisco was chaotic. Committees of Vigilance were formed in 1851, and again in 1856, in response to rising crime and government corruption. This popular militia movement arrested, tried, and executed a total of 12 men, arrested hundreds of Irishmen and government militia members, and forced several elected officials to resign.[16] The Committee of Vigilance relinquished power both times after it decided the city had been "cleaned up." Mob activity later focused on Chinese immigrants, creating many race riots.[17] These riots culminated in the creation of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that aimed to reduce Chinese immigration to the United States by limiting immigration to males and reducing numbers of immigrants allowed in the city.[18][19] The law was not repealed until 1943 with the Magnuson Act.

San Francisco was the county seat of San Francisco County, one of state's 18 original counties since California's statehood in 1850. Until 1856, the city limits extended west to Divisadero Street and Castro Street, and south to 20th Street. In response to the lawlessness and vigilantism that escalated rapidly between 1855 and 1856, the California government decided to divide the county. A straight line was then drawn across the tip of the San Francisco Peninsula just north of San Bruno Mountain. Everything south of the line became San Mateo County while everything north of the line became the new consolidated City and County of San Francisco, to date the only consolidated city-county in California.[20][21]

In autumn of 1855, a ship bearing refugees from an ongoing cholera epidemic in the Far East (authorities disagree as to whether this was the S.S. Uncle Sam or the S.S. Carolina but primary documents indicate that the Carolina was involved in the epidemic of 1850 and the Uncle Sam in the epidemic of 1855) docked in San Francisco. Since the city's rapid Gold Rush population growth had significantly outstripped the development of infrastructure, including sanitation, a serious cholera epidemic quickly broke out. The responsibility for caring for the indigent sick had previously rested on the state, but faced with the San Francisco cholera epidemic, the state legislature devolved this responsibility to the counties, setting the precedent for California's system of county hospitals for the poor still in effect today. The Sisters of Mercy were contracted to run San Francisco's first county hospital, the State Marine and County Hospital, due to their efficiency in handling the cholera epidemic of 1855. By 1857, the order opened St. Mary's Hospital on Stockton Street, the first Catholic hospital west of the Rocky Mountains. In 1905, The Sisters of Mercy purchased a lot at Fulton and Stanyan Streets, the current location of St. Mary's Medical Center, the oldest continually operating hospital in San Francisco.

Due to the Gold Rush, and despite the Vigilantes, and the gradual implementation of law and order in San Francisco, its red-light district at the time became known as the Barbary Coast which became a hotbed of gambling, prostitution and most notoriously for Shanghaiing. It is now overlapped by Chinatown, North Beach, Jackson Square, and the Financial District.

Paris of the West

It was during the 1860s to the 1880s when San Francisco began to transform into a major city, starting with massive expansion in all directions, creating new neighborhoods such as the Western Addition, the Haight-Ashbury, Eureka Valley, the Mission District, culminating in the construction of Golden Gate Park in 1887. In 1864 Hugh H. Toland, a South Carolina surgeon who found great success and wealth after moving to San Francisco, founded the Toland Medical College, which became one of three affiliated colleges, which later developed into the University of California, San Francisco. Initially, the affiliated colleges were located at different sites around San Francisco, but near the end of the 19th century interest in bringing them together grew. To make this possible, San Francisco Mayor Adolph Sutro donated 13 acres in Parnassus Heights at the base of Mount Parnassus (now known as Mount Sutro). The new site, overlooking Golden Gate Park, opened in the fall of 1898, with the construction of the new affiliated colleges buildings.

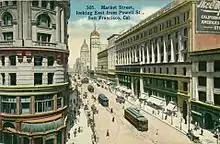

The city's famous cable cars were built around this time, a unique invention devised by Andrew Smith Hallidie in order to traverse the city's steep hills while connecting the new residential developments. San Francisco grew in cultural prominence at this time as famous writers Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Oscar Wilde spent time in the city, while local characters developed such as Emperor Norton. The San Francisco Stock and Bond Exchange was founded in 1882.[22]

By the 1890s, San Francisco, like many cities across the United States, was suffering from machine politics and corruption, and was ripe for political reform. Adolph Sutro ran for mayor in 1894 under the auspices of the Populist Party and won handily without campaigning. Unfortunately, except for the Sutro Baths, Mayor Sutro substantially failed in his efforts to improve the city. The next mayor, James D. Phelan elected in 1896, was more successful, pushing through a new city charter that allowed for the ability to raise funds through bond issues. He got bonds passed to construct a new sewer system, 17 new schools, two parks, a hospital, and a main library. After leaving office in 1901, Phelan became interested in remaking San Francisco into a grand and modern Paris of the West.

In 1900, a ship brought with it rats infected with bubonic plague to initiate the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904; the first plague epidemic in the continental U.S. Mistakenly believing that interred corpses contributed to the transmission of plague, and possibly motivated by the opportunity for profitable land speculation, city leaders banned all burials within the city. Cemeteries moved to the undeveloped area just south of the city limit, now the town of Colma, California. A 15-block section of Chinatown was quarantined while city leaders squabbled over the proper course to take, but the outbreak finally was eradicated by 1905. However, the problem of existing cemeteries and the shortage of land in the city remained. In 1912 (with fights extending until 1942), all remaining cemeteries in the city were evicted to Colma, where the dead now outnumber the living by more than 1,000 to one. The above-ground Columbarium of San Francisco was allowed to remain, as well as the historic cemetery at Mission Dolores, the grave of Thomas Starr King at the First Unitarian Church, and the San Francisco National Cemetery at the Presidio of San Francisco.[23]

Corruption and graft trials

Mayor Eugene Schmitz, president of the Musician's Union, was chosen by political leader Abe Ruef to run for mayor as a front for the Union Labor Party in 1901. He and Ruef had been friends for 18 years.[24] Ruef contributed $16,000 (about $521,000 today) to Schmitz' campaign[25]: p14 and used his considerable influence to make sure Schmitz was selected to front for the new Union Labor Party.[25][26][27] Ruef wrote the Union Labor Party's platform and built a strong, behind-the-scenes network of supporters, including the more than 5,000 saloon keepers and another 2,000 bartenders in San Francisco, who all influenced political discussions in their saloons.[27]

Schmitz was less corrupt than the mayors who preceded him,[28] but he had to deal with Ruef who operated from his offices at California and Kearney Streets. He wrote most of the mayor's official papers and conducted an ongoing series of meetings with Mayor Schmitz, city commissioners, officials, seekers of favors or jobs, and others. Officially an unpaid attorney for the mayor's office, he was the power behind the mayor's chair.[27]

Former Mayor Phelan, in concert with Rudolph Spreckels, president of the San Francisco First National Bank, and Fremont Older, editor of the San Francisco Bulletin, decided to try to challenge the Labor Party's corrupt choke-hold on city politics and commerce.[28] They got Francis Heney, a U.S. special prosecutor, to help with the investigation and prosecution. Heney eventually charged Ruef and Schmitz with numerous counts of bribery and brought them to trial.

On June 13, 1907, Mayor E. E. Schmitz was found guilty of extortion and the office of Mayor was declared vacant. He was sent to jail to await sentence. Shortly thereafter he was sentenced to five years at San Quentin State Prison, the maximum sentence the law allowed. He immediately appealed. While awaiting the outcome of the appeal, Schmitz was kept in a cell in San Francisco County Jail.[29] Dr. Edward R. Taylor, Dean of Hastings College, agreed to step in as interim mayor and was given power to appoint new supervisors to replace those who had resigned.[25] Ruef was found guilty and was sentenced to 14 years in prison. In November 1910, his conviction and sentence were finally upheld, and on March 1, 1911, he entered prison.[25][27] On August 23, 1915, having served a little more than four and a half of his fourteen-year sentence, he was released. He was the only person in the entire investigation who went to prison. He was not allowed to return to his legal practice. "Before he went to prison he had been worth over a million dollars, when he died he was bankrupt."[30]: 257

1906 earthquake and fire

On April 18, 1906, a devastating earthquake resulted from the rupture of over 270 miles of the San Andreas Fault, from San Juan Bautista to Eureka, centered immediately offshore of San Francisco. The quake is estimated by the USGS to have had a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. Water mains ruptured throughout San Francisco, and the fires that followed burned out of control for days, destroying approximately 80% of the city, including almost all of the downtown core. Many residents were trapped between the water on three sides and the approaching fire, and a mass evacuation across the Bay saved thousands. Refugee camps were also set up in Golden Gate Park, Ocean Beach, and other undeveloped sections of the city. The official death toll at the time was 478, although it was officially revised in 2005 to 3,000+. The initial low death toll was concocted by civic, state, and federal officials who felt that reporting the actual numbers would hurt rebuilding and redevelopment efforts, as well as city and national morale. The death toll from this event had the highest number of deaths from a natural disaster in California history.

Reconstruction

Almost immediately after the quake re-planning and reconstruction plans were hatched to quickly rebuild the city. One of the more famous and ambitious plans, proposed before the fire, came from famed urban planner, Daniel Burnham. His bold plan called for Haussmann style avenues, boulevards, and arterial thoroughfares that radiated across the city, a massive civic center complex with classical structures, what would have been the largest urban park in the world, stretching from Twin Peaks to Lake Merced with a large athenaeum at its peak, and various other proposals. This plan was dismissed by critics (both at the time and now), as impractical and unrealistic to municipal supply and demand. Property owners and the Real Estate industry were against the idea as well due to the amounts of their land the city would have to purchase to realize such proposals. While the original street grid was restored, many of Burnham's proposals eventually saw the light of day such as a neo-classical civic center complex, wider streets, a preference of arterial thoroughfares, a subway under Market Street, a more people-friendly Fisherman's Wharf, and a monument to the city on Telegraph Hill, Coit Tower. With many rats and people displaced, a minor outbreak of plague occurred in San Francisco and Oakland during reconstruction, but unlike the 1901-1904 outbreak, government authorities responded quickly.[31]

"Greater San Francisco" movement of 1912

In 1912, there was a movement to create a Greater San Francisco in which southern Marin County, the part of Alameda County which includes Oakland, Piedmont and Berkeley, and northern San Mateo County from San Bruno northwards would have become outer Boroughs of San Francisco, with the City and County of San Francisco functioning as Manhattan, based on the New York City model. East Bay opposition defeated the San Francisco expansion plan in the California legislature, and later attempts at San Francisco Bay Area metropolitan area consolidation in 1917, 1923, and 1928 also failed to be implemented.[32][33]

Panama–Pacific Exposition of 1915

In 1915, the city hosted the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, officially to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal, but also as a showcase of the vibrant completely rebuilt city less than a decade after the earthquake. After the exposition ended, all of its grand buildings were demolished except for the rebuilt Palace of Fine Arts which survives today in an abbreviated form, while the remainder of the fairgrounds were re-developed into the Marina District.

1930s – World War II

_enters_San_Francisco_Bay%252C_December_1942.jpg.webp)

1934 saw San Francisco become the center of the West Coast waterfront strike. The strike lasted eighty-three days and saw the deaths of two workers, but the result led to the unionization of all of the West Coast ports of the United States.

The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge was opened in 1936 and the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937. The 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition was held on Treasure Island. It was in this period that the island of Alcatraz, a former military stockade, began its service as a federal maximum security prison, housing notorious inmates such as Al Capone, and Robert Franklin Stroud, The Birdman of Alcatraz.

During World War II, San Francisco was the major mainland supply point and port of embarkation for the war in the Pacific. It also saw the largest and oldest enclave of Japanese outside of Japan, Japantown, completely remove all of its ethnic Japanese residents as a result of Executive Order 9066 that forced all Japanese of birth or descent in the United States to be interned. The city-owned Sharp Park in Pacifica opened as an internment camp in 1942.[34] By 1943 many large sections of Japantown remained vacant due to the forced internment.

The void was quickly filled by thousands of African Americans who had left the South to find wartime industrial jobs in California as part of the Great Migration. Many African Americans also settled in the Fillmore District and most notably near the Bayview-Hunters Point shipyards, working in the dry-docks there. The same docks at Hunters Point would be used for loading the key fissile components of the first atomic bomb onto the USS Indianapolis in July 1945 for transfer to Tinian.

The War Memorial Opera House which opened in 1932, was the site of some significant post World War II history. In 1945, the conference that formed the United Nations was held there, with the UN Charter being signed nearby in the Herbst Theatre on June 26. Additionally the Treaty of San Francisco which formally ended war with Japan and established peaceful relations, was drafted and signed here six years later in 1951.

Post-World War II

After World War II, many American military personnel, who fell in love with the city while leaving for or returning from the Pacific, settled in the city, prompting the creation of the Sunset District, Visitacion Valley, and the total build out of San Francisco. During this period, Caltrans commenced an aggressive freeway construction program in the Bay Area. However, Caltrans soon encountered strong resistance in San Francisco, for the city's high population density meant that virtually any right-of-way would displace a large number of people. Caltrans tried to minimize displacement (and its land acquisition costs) by building double-decker freeways, but the crude state of civil engineering at that time resulted in construction of some embarrassingly ugly freeways which ultimately turned out to be seismically unsafe. In 1959, the Board of Supervisors voted to halt construction of any more freeways in the city, an event known as the Freeway Revolt.[35] Although some minor modifications have been allowed to the ends of existing freeways, the city's anti-freeway policy has remained in place ever since.

The San Francisco Mental Hygiene Society was formed in 1947. In 1956, nearly a hundred LGBT San Franciscans were arrested during the Hazel's Inn raid, during a widespread crackdowns on gay bars.[36] In 1958 the New York Giants moved to San Francisco and became the San Francisco Giants. Their first stadium, Candlestick Park, was constructed in 1959.

Urban renewal

In the 1950s San Francisco mayor George Christopher hired M. Justin Herman to head the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA). Justin Herman began an aggressive campaign to tear down blighted areas of the city that were working class, non-white neighborhoods. Enacting eminent domain whenever necessary, he set upon a plan to tear down huge areas of the city and replace them with modern construction. Critics accused Herman of racism for what was perceived as attempts to create segregation and displacement of blacks. Many black residents were forced to move from their homes near the Fillmore jazz district to newly constructed projects such as near the naval base at Hunter's Point or even to other cities such as Oakland. He began leveling entire areas in San Francisco's Western Addition and Japantown neighborhoods. Herman also completed the final removal of the produce district below Telegraph Hill, moving the produce merchants to the Alemany Boulevard site. His planning led to the creation of Embarcadero Center, the Embarcadero Freeway, Japantown, the Geary Street superblocks, and eventually Yerba Buena Gardens.

1960 – 1970s

"Summer of Love" and counterculture movement

Following World War II, San Francisco became a magnet for America's counterculture. During the 1950s, City Lights Bookstore in the North Beach neighborhood was an important publisher of Beat Generation literature. Some of the story of the evolving arts scene of the 1950s is told in the article San Francisco Renaissance. During the latter half of the following decade, the 1960s, San Francisco was the center of hippie and other alternative culture.

In 1967, thousands of young people entered the Haight-Ashbury district during what became known as the Summer of Love. The San Francisco Sound emerged as an influential force in rock music, with such acts as Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead achieving international prominence. These groups blurred the boundaries between folk, rock and jazz traditions and further developed rock's lyrical content.

Rise of the "Gay Mecca"

San Francisco's frontier spirit and wild and ribald character started its reputation as a gay mecca in the first half of the 20th century. World War II saw a jump in the gay population when the US military actively sought out and dishonorably discharged homosexuals. From 1941 to 1945, more than 9,000 gay servicemen and women were discharged, and many were processed out in San Francisco.[37]

The late 1960s also brought in a new wave of lesbians and gays who were more radical and less mainstream and who had flocked to San Francisco not only for its gay-friendly reputation, but for its reputation as a radical, left-wing center. These new residents were the prime movers of Gay Liberation and often lived communally, buying decrepit Victorians in the Haight and fixing them up. When drugs and violence began to become a serious problem in the Haight, many lesbians and gays simply moved "over the hill" to the Castro replacing Irish-Americans who had moved to the more affluent and culturally homogeneous suburbs.

The Castro became known as a Gay Mecca, and its gay population swelled as significant numbers of gay people moved to San Francisco in the 1970s and 1980s. The growth of the gay population caused tensions with some of the established ethnic groups in the southern part of the city. In 1977, businessman Harvey Milk announced he would run for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors at a memorial for Robert Hillsborough, a gay man murdered in a homophobic attack.[38] Milk won the election and became San Francisco's first openly gay elected official.

On November 27, 1978 Dan White, a former member of the Board of Supervisors and former police officer, assassinated the city's mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Milk. The murders and the subsequent trial were marked both by candlelight vigils and homosexual riots. In the 1980s, HIV (formerly called LAV, HTLV-III, also known as AIDS virus) created havoc in the gay community. The gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender population of the city is still the highest of any major metropolitan area in the United States.[39]

New public infrastructure

The 1970s also brought other major changes to the city such as the construction of its first subway system, BART, which connects San Francisco with other cities in the Bay Area; it was installed in 1972. At stations in downtown San Francisco, BART connects with Muni, the city subway, which has lines that run underground along Market Street, and then along surface streets through much of the city. San Francisco's second tallest building, the Transamerica Pyramid was also completed during that year.

1980s

During the administration of Mayor Dianne Feinstein (1978–1988), San Francisco saw a development boom referred to as "Manhattanization." Many large skyscrapers were built—primarily in the Financial District—but the boom also included high-rise condominiums in some residential neighborhoods. An opposition movement gained traction among those who felt the skyscrapers ruined views and destroyed San Francisco's unique character. Similar to the freeway revolt in the city decades earlier, a "skyscraper revolt" forced the city to embed height restrictions in the planning code. For many years, the limits slowed construction of new skyscrapers. She had also spearheaded the development and construction of the city's convention center, the Moscone Center, preserved and renovated the city's Cable Cars, and attracted the 1984 Democratic National Convention.

During the early 1980s, homeless people began appearing in large numbers in the city, the result of multiple factors including the closing of state institutions for the mentally ill, the Reagan administration reducing Section 8 housing benefits, and social changes which increased the availability of addictive drugs. Combined with San Francisco's attractive environment and generous welfare policies the problem soon became endemic. Mayor Art Agnos (1988–92) was the first to attack the problem, and not the last; it is a top issue for San Franciscans even today. His program, Beyond Shelter, became the basis for federal programs and was recognized by Harvard for Innovations in Local Government. Agnos allowed the homeless to camp in the Civic Center park after the Loma Prieta earthquake that made over 1,000 SRO's uninhabitable, which led to its title of "Camp Agnos." His opponent used this to attack Agnos in 1991, an election Agnos lost. Frank Jordan launched the "MATRIX" program the next year, which aimed to displace the homeless through aggressive police action. And it did displace them-to the rest of the city. His successor, Willie Lewis Brown Jr., was able to largely ignore the problem, riding on the strong economy into a second term. Later, mayor Gavin Newsom created the controversial "Care Not Cash" program and policy on the homeless, which calls for ending the city's generous welfare policies towards the homeless and instead placing them in affordable housing and requiring them to attend city funded drug rehabilitation and job training programs.

In August 1989, San Francisco was surpassed for the first time in population by San Jose (located in Silicon Valley), the world center of the computer industry. San Jose has continued since then to grow in population since it is surrounded by large tracts of developable land. Thus, San Francisco is now the second largest city in population in the San Francisco Bay Area after San Jose.

1989 Loma Prieta earthquake

On October 17, 1989, an earthquake measuring 6.9 on the moment magnitude scale struck on the San Andreas Fault near Loma Prieta Peak in the Santa Cruz mountains, approximately 70 miles (113 km) south of San Francisco, a few minutes before Game 3 of the 1989 World Series was scheduled to begin at Candlestick Park. The quake severely damaged many of the city's freeways including the Embarcadero Freeway and the Central Freeway. Mayor Agnos made the controversial decision to tear down the Embarcadero Freeway, opening the waterfront but eventually shifting Chinatown voters away from him and costing him re-election in 1991. The quake also caused extensive damage in the Marina District and the South of Market neighborhoods.

1990s

The 1990s saw the demolition of the quake damaged Embarcadero and Central Freeway, restoring the once blighted Hayes Valley as well as the city's waterfront promenade, The Embarcadero. In 1994 as part of the Base Realignment and Closure plan, the former military base of San Francisco Naval Shipyard in Bayview-Hunters Point was closed and returned to the city while the Presidio was turned over to the National Park Service and since converted into a national park.

In 1996, the city elected its first African American mayor, former Speaker of the California State Assembly, Willie Brown. Brown called for expansions to the San Francisco budget to provide for new employees and programs. During Brown's tenure, San Francisco's budget increased to US$5.2 billion and the city added 4,000 new employees. His tenure saw the development and construction of the new Mission Bay neighborhood, and a baseball stadium for the Giants, AT&T Park which was 100% privately financed.

In 1997, the Pinecrest Diner, a popular all-night diner-style restaurant in San Francisco, became notorious for a murder over an order of eggs.[40]

Dot-com boom

During the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, large numbers of entrepreneurs and computer software professionals moved into the city, followed by marketing and sales professionals, and changed the social landscape as once poorer neighborhoods became gentrified. The rising rents forced many people, families, and businesses to leave. San Francisco has the smallest share of children of any major U.S. city, with the city's 18 and under population at just 13.4 percent.[41]

2000s

In 2001, the markets crashed, the boom ended, and many left San Francisco. South of Market, where many dot-com(.com) companies were located, had been bustling and crowded with few vacancies, but by 2002 was a virtual wasteland of empty offices and for-rent signs. Much of the boom was blamed for the city's "fastest shrinking population", reducing the city's population by 30,000 in just a few years. While the bust helped put an ease on the city's apartment rents, the city remained expensive. Also that year, Diane Whipple, a 33-year-old lacrosse coach, was killed by two Presa Canario dogs owned by her neighbors, who were charged with murder.

By 2003, the city's economy had recovered from the dot-com crash thanks to a resurgent international tourist industry and the Web 2.0 boom that saw the creation of many new internet and software start-up companies in the city, attracting white-collar workers, recent University graduates, and young adults from all over the world.[42][43] Residential demand as well as rents rose again, and as a result city officials relaxed building height restrictions and zoning codes to construct residential condominiums in SOMA such as One Rincon Hill, 300 Spear Street, and Millennium Tower, although the late 2000s recession has indefinitely halted many construction projects such as Rincon Hill.[44] Part of this development included the reconstruction of the Transbay Terminal Replacement Project.

2010s

The early 2000s and into the 2010s saw the redevelopment of the Mission Bay neighborhood. Originally an industrial district, it underwent development fueled by the construction of the University of California, San Francisco Mission Bay campus and its UCSF Medical Center, and is currently an up-and-coming neighborhood, undergoing development and construction. It has rapidly evolved into a wealthy neighborhood of luxury condominiums, hospitals, and biotechnology research and development. It is also the site of the Chase Center, the arena of the Golden State Warriors and the new Uber headquarters.

2010 saw the San Francisco Giants win their first World Series title since moving from New York City in 1958. The estimated 1 million people who attended their victory parade is considered one of the largest in city history.[45] 2012 saw the Giants win their second title in San Francisco, and 2014 saw them win their third. Celebrations citywide were marred by rioting which caused millions of dollars in property damage.[46][47]

In 2011, city manager Edwin Lee was elected the first Chinese American mayor in any American major city. Mayor Lee has been a strong proponent of tenant's rights, but also a business-friendly mayor to the city's burgeoning tech community.

By 2013, San Francisco, with thanks from the Web 2.0 boom, had fully recovered from the late 2000s recession and is experiencing a real estate and population boom. The computer industry is moving north from Silicon Valley. Availability of vacant rental units is scarce and the prices for vacant units has increased dramatically, and as of 2015 is reported to be the highest in the nation.[48]

In April 2016, the city passed a law requiring all new buildings below 10 stories to have rooftop solar panels, making it the first major US city to do so.[49]

In 2018, San Francisco Supervisor London Breed was elected mayor.

2020

On March 16, 2020, San Francisco was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which put tens of thousands of residents out of work, and shifted others to work at home. Rent prices fell and vacancies increased.[50][51] That same year, severe wildfires, including the North Complex Fire, burned more than 2 million acres east of San Francisco, resulting in Orange Skies Day.[52]

Historic populations

|

|

See also

References

- "The Global Financial Centres Index 22" (PDF). Financial Centre Futures. September 2017. p. 4. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

Centre: San Francisco GFCI 22 Rank: 16 GFCI 22 Rating: 693

- Margolin, Malcolm (1978). The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-0-93058-801-4.

- Skowronek, Russell (1998). "Sifting the Evidence: Perceptions of life at the Ohlone (Costanoan) Missions of Alta California". Ethnohistory. 45 (4): 675–708. doi:10.2307/483300. JSTOR 483300.

- Billiter, Bill (January 1, 1985). "3,000-Year-Old Connection Claimed : Siberia Tie to California Tribes Cited". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

The California Indians' name for what is now San Francisco, Von Sadovszky [sic], was "awas-te." He said that expression "would be understood today by the Siberians" and means "place at the bay.

- Bean, Lowell John, ed. (1994). Ohlone Past and Present. Ballena Press anthropological papers, no. 42. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press. ISBN 978-0-87919-130-6.

- Engstrand, Iris (1997). "Seekers of the Northern Mystery". California History. 76 (2–3): 78–110. doi:10.2307/25161663. JSTOR 25161663.

- "Visitors: San Francisco Historical Information". City and County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- De La Perouse, Jean-François; Margolin, Malcolm & Yamane, Linda Gonsalves (1989). Life in a California Mission: Monterey in 1786 : The Journals of Jean François De La Perouse. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-0-930588-39-7.

- For the Revillagigedo Census of 1790, see "The Census of 1790, California". California Spanish Genealogy. Retrieved August 4, 2008. Compiled from: Mason, William Marvin (1998). The Census of 1790: A Demographic History of California. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press. pp. 75–105. ISBN 978-0-87919-137-5.

- "Vancouver's Report". Presidio of San Francisco. National Park Service. June 21, 2003. Archived from the original on April 4, 2005. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

[...]When Vancouver discovered that the Presidio's walls were of earthen construction and could not defend against modern artillery, he exposed the high vulnerability of the Presidio's fortifications. He also gave a detailed description of the Presidio's infrastructure, which further compromised the Presidio's defenses:[...]

- "From the 1820s to the Gold Rush". The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- Porter, Andrew (1999). The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume III: The Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820565-4.

- "History of Yerba Buena Gardens". Yerba Buena Gardens. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2003.

- Hittell, Theodore H. (1885). History of California. Oakland, CA: Pacific Press Publishing Co. p. 596.

- Powers, Dennis (2006). Treasure Ship: The Legend and Legacy of the S.S. Brother Jonathan. New York City: Kensington/Citadel Press.

- Mary Floyd Williams, History of the San Francisco Committee of vigilance of 1851: a study of social control on the California frontier in the days of the gold rush (U of California Press, 1921) online.

- Bodenner, Chris (October 20, 2006). "Issues & Controversies in American History: Chinese Exclusion Act". FACTS.com. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ""Our Misery and Despair": Kearney Blasts Chinese Immigration". Indianapolis Times. February 28, 1878 – via History Matters.

- Bailey, Thomas A.; Kennedy, David M. & Cohen, Lizabeth (2002) [1956]. The American Pageant (12th ed.). New York City: Houghton Mifflin.

- "Maps of California". California Genealogy 101. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013.

- "Does San Francisco have a City Council?". City and County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- "Trading Floor's Final Day At Pacific Stock Exchange". The New York Times. Reuters. May 26, 2001. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- Blackett, John W. "San Francisco Cemeteries". San Francisco Cemeteries. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2005.

[...]First there were a number of expulsions that began at the turn of the century and they continued again in the 1930s and 1940s until almost all cemeteries were eliminated within The City. Unclaimed headstones and monuments were recycled for building various seawalls, landfills and park gutters. Basically, it is illegal to actually cremate anyone in town or bury anyone in the ground in San Francisco, California...proper. The only exception today is the San Francisco National Cemetery/The Presidio. The five Columbariums and the Memorial Terrace, of course, are for the interment of ashes only.

- Waldorf, Delores. "S.F. Labor's First Fight For 10-Hour Day". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- Hichborn, Frank (1915). The System. San Francisco: The James H. Barry Company. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- "Abe Ruef – America's Most Erudite City Boss". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Carlsson, Chris. "Abe Ruef and the Union Labor Party". Found SF. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- Ladd, Thomas (2007). "Arming Goons: Mayor Phelan Arms the Strikebreakers in the 1901 City Front Strike" (PDF). Ex Post Facto. XVI. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- "Mayor Schmitz Found Guilty" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1907. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- Thomas, Gordon; Witts, Max Morgan (1971). The San Francisco Earthquake. New York: Stein & Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1360-9.

- Dolan, Brian (2006). "Plague in San Francisco (1900)". Public Health Reports. 121: 16–37. doi:10.1177/00333549061210S103. PMID 16550761.

- Siegel, Fred (Fall 1999). "Is Regional Government the Answer?" (PDF). The Public Interest. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- Berkeley, Mel Scott (1985). "Chapter 9: The Greater San Francisco Movement". The San Francisco Bay Area — A Metropolis in Perspective. University of California Press. pp. 133–148. ISBN 978-0-52005-510-0.

- Kamiya, Gary. "The dark past of San Francisco's Sharp Park". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- Dyble, Louise Nelson (October 11, 2011). Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics, and the Golden Gate Bridge. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-8122-0688-3.

In 1959, San Francisco supervisors put a sudden halt to the construction of all freeways in the city with their famous "freeway revolt." They voted unanimously to deny permission for street closures, which was required under California law, hoping to negotiate less destructive street improvements or state subsidies for the construction of a tunnel instead. Several federally funded interstate projects were ultimately scrapped, much to the dismay of pro-growth state officials and businessmen.

- Perkins, Laura. "Police raid gay gathering". SFGATE. Retrieved June 30, 2023.

- Berube, Allan (1990). Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-1071-3.

- Richard Peddicord (1996). "Gay and Lesbian Rights: A Question--sexual Ethics Or Social Justice?". Rowman & Littlefield. p. 84–85. ISBN 9781556127595. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- "San Francisco Metro Area Ranks Highest in LGBT Percentage". Gallup. March 20, 2015.

- Davis, Lisa (September 6, 2000). "A Killer Dies, a Mystery Lingers". San Francisco Weekly.

- "San Francisco County QuickFacts". US Census Bureau.

- Hendricks, Tyche (June 22, 2006). "Rich City Poor City / Middle-class neighborhoods are disappearing from the nation's cities, leaving only high- and low-income districts, new study says". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "An Overview of San Francisco's Recent Economic Performance: Executive Summary" (PDF). City and County of San Francisco. April 3, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- Coté, John (October 7, 2009). "S.F. sets tougher deadlines for condo tower fee". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Fagan, Kevin; Berton, Justin; Bulwa, Demian (June 27, 2011). "Hundreds of thousands pack Giants parade route". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Ho, Vivian (October 31, 2012). "San Francisco gets tough on Giants rioters". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Weise, Elizabeth (October 29, 2012). "Giants win in World Series spawns riot in San Francisco". USA Today.

- Capperis, Sean; Gould Ellen, Ingrid; Karfunkel, Brian (May 28, 2015). Renting in America's Largest Cities (PDF) (Report). NYU Furman Center/Capital One. p. 40.

- Domonoske, Camila (April 20, 2016). "San Francisco Requires New Buildings To Install Solar Panels". NPR.

- Keeling, Brock (June 2, 2020). "San Francisco rent prices see 'unprecedented' drop". Curbed SF.

- Hwang, Kellie (December 1, 2020). "New data show S.F. Is still a renter's market. Will Bay Area prices rebound in the spring?". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Fuller, Thomas. "Wildfires Blot Out Sun in the Bay Area". New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- 1850 census was lost in fire. This is the figure for 1852 California Census.

- 1940 Census. Population Report. Vol. 1. p. 32-33

- "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers California's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

Further reading

Surveys

- Barth, Gunther Paul (1975). Instant Cities: Urbanization and the Rise of San Francisco and Denver. Oxford University Press.

- Issel, William & Cherny, Robert W. (1986). San Francisco, 1865–1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development. University of California Press.

- Richards, Rand (2007). Historic San Francisco: A Concise History and Guide. ISBN 978-1879367050.

- Ryan, Mary P. (1997). Civic Wars: Democracy and Public Life in the American City during the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204417. Comparative survey of San Franciso, New York, and New Orleans.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2010). Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26250-8.; online review

- Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California Dream, 1850–1915. Starr's multivolume history of the state has extensive coverage of the city's politics, culture and economy.

Cultural themes

- Berglund, Barbara (2007). Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846–1906.

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence (1980). Literary San Francisco: A Pictorial History from its Beginnings to the Present Day. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-250325-1. OCLC 6683688.

- Maupin, Armistead (1978). Tales of the City. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-096404-7. OCLC 29847673.

- Sinclair, Mick (2003). San Francisco: A Cultural and Literary History.

Earthquake, infrastructure & environment

- Bronson, William (2006). The Earth Shook, the Sky Burned. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5047-6. OCLC 65223734.

- Cassady, Stephen (1987). Spanning the Gate. Square Books. ISBN 978-0-916290-36-8. OCLC 15229396.

- Davies, Andrea Rees (2011). Saving San Francisco: Relief and Recovery after the 1906 Disaster.

- Dillon, Richard H. (1998). High Steel: Building the Bridges Across San Francisco Bay. Celestial Arts (Reissue edition). ISBN 978-0-88029-428-7. OCLC 22719465.

- Dreyfus, Philip J. (2009). Our Better Nature: Environment and the Making of San Francisco.

- Franklin, Philip (2006). The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906: How San Francisco Nearly Destroyed Itself.

- Thomas, Gordon; Witts, Max Morgan (1971). The San Francisco Earthquake. Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1360-9. OCLC 154735.

Ethnicity, religion & race

- Broussard, Albert S. (1994). Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900–1954.

- Burchell, R. A. (1980). The San Francisco Irish, 1848–1880.

- Chen, Yong (2002). Chinese San Francisco, 1850–1943: A Trans-Pacific Community.

- Cordova, Cary (2017). The Heart of the Mission: Latino Art and Politics in San Francisco.

- Daniels, Douglas Henry (1980). Pioneer Urbanites: A Social and Cultural History of Black San Francisco. University of California Press.

- Garibaldi, Rayna; Hooper, Bernadette C. (2008). Catholics of San Francisco.

- Gribble, Richard (2006). An Archbishop for the People: The Life of Edward J. Hanna. The Catholic archbishop (1915–1935).

- Kim, Jae Yeon. "Racism is not enough: Minority coalition building in San Francisco, Seattle, and Vancouver." Studies in American Political Development 34.2 (2020): 195-215. online

- Rosenbaum, Fred (2011). Cosmopolitans: A Social and Cultural History of the Jews of the San Francisco Bay Area.

- Yung, Judy (1995). Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco.

Gold rush & early days

- Hittell, John S. (1878). A History of the City of San Francisco and incidentally of the State of California.

- Lotchin, Roger W. (1997). San Francisco, 1846–1856: From Hamlet to City. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06631-3. OCLC 35650934.

- Richards, Rand (2008). Mud, Blood, and Gold: San Francisco in 1849.

- Taniguchi, Nancy J. Dirty Deeds: Land, Violence, and the 1856 San Francisco Vigilance Committee (2016) excerpt

Politics

- Agee, Christopher Lowen (2014). The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Liberal Politics, 1950–1972.

- Bean, Walton (1967). Boss Rueff's San Francisco: The Story of the Union Labor Party, Big Business, and the Graft Prosecution.

- Carlsson, Chris; Elliott, LisaRuth (2011). Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968–1978.

- DeLeon, Richard E. (1992). Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975–1991.

- Ethington, Philip J. (2001). The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850–1900.

- Hartman, Chester (2002). City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08605-0. OCLC 48579085.

- Holli, Melvin G., and Jones, Peter d'A., eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980 (Greenwood Press, 1981) short scholarly biographies each of the city's mayors 1820 to 1980. online; see index at p. 410 for list.

- Howell, Ocean (2015). Making the Mission: Planning and Ethnicity in the Mission. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kahn, Judd (1979). Imperial San Francisco: Politics and Planning in an American City, 1897–1906. University of Nebraska Press.

- Issel, William (2013). Church and State in the City: Catholics and Politics in Twentieth-Century San Francisco. Temple University Press.

- Kazin, Michael (1988). Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era.

- Saxton, Alexander (1965). "San Francisco labor and the populist and progressive insurgencies". Pacific Historical Review. 34 (4): 421–438. doi:10.2307/3636353. JSTOR 3636353.

Social and ethnic

- Asbury, Hubert (1989). The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. Dorset Press. ISBN 978-0-88029-428-7. OCLC 22719465.

- Lotchin, Roger W. (2003). The Bad City in the Good War: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego.

- McDonald, Terrence J. (1987). The Parameters of Urban Fiscal Policy: Socioeconomic Change and Political Culture in San Francisco, 1860–1906.

External links

- "History of Yerba Buena's Renaming". San Francisco History Podcast.

- "Shaping San Francisco, the lost history of San Francisco".

- "Found SF wiki project".

- "Historic Pictures of 19th Century San Francisco". Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum.

- "Historic San Francisco photographs, including the 1906 Earthquake and Fire". JB Monaco, a local photographer during that period.

- "Videos of San Francisco from the Prelinger Collection". Archive.org.

- "Videos of San Francisco from the Shaping San Francisco collection". Archive.org.

- "San Francisco Then and Now". LIFE.

- Across From City Hall on YouTube video on the "Camp Agnos" era at Civic Center Plaza.

- "These coders used 13,000 old photos to make a Google Street View map of San Francisco in the 1800s". Business Insider. August 28, 2016.