History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

The History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa refers to the history of the modern-day Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

| History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

|---|

|

| History of Pakistan |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

The earliest evidence from the region indicates that trade was common via the Khyber Pass; originating from the Indus Valley Civilization. The Vedic culture reached its peak between the 6th and 1st centuries B.C under the Gandharan Civilization, and was identified as a center of Hindu and Buddhist learning and scholarship.[1]

Following Alexander the Great's invasion, the region became part of the Mauryan Empire, followed by the Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians.

The region of Gandhara reached its height under Kushan Empire in 2nd and 3rd century AD. Over time the Turk Shahis managed to gain control of the region and ruled starting from around the sixth century, but were later overthrown by the Hindu Shahis.[2] The Hindu Shahis were finally destroyed after the defeat of King Jayapala in A.D 1001 by the Ghaznavids led by Mahmud of Ghazni. After the Ghaznavids, various other Islamic rulers had managed to invade the region, with the most notable being the Delhi Sultanates who had with respect to various dynasties ruled starting from A.D 1206. The Mughals had taken control of the region, and managed to rule until the early 18th century when they were displaced by the rule of the Durranis and briefly by Barakzai Dynasty until early 19th century. After the end of Durrani rule, modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa became part of the Sikh empire, who later lost the territory to the British Empire around 1857, and had ruled until the Indo-Pakistani Independence of 1947. After the independence of Pakistan, the area was renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after widespread petitioning to the Pakistan government by the local Pashtuns. Today, the area is a key province in the war on terror; and aside from terrorism, the province continues to face many developmental challenges.

Bronze age

Indus Valley Civilization

During the times of Indus Valley civilisation (3300 BCE – 1700 BCE) the Khyber Pass through Hindu Kush provided a route to other neighbouring empires and was used by merchants on trade excursions.[3]

Iron age

Vedic era

The region of Gandhara, which was primarily based in the area of modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa features prominently in the Rigveda (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BCE),[4][5] as well as the Zoroastrian Avesta, which mentions it as Vaēkərəta, the sixth most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda. It was one of the 16 Mahajanapadas of Vedic era.[6][7][8] It was the centre of Vedic and later forms of Hinduism. Gandhara was frequently mentioned in Vedic epics, including Rig Veda, Ramayana and Mahabharata. It was the home of Gandhari, the princess of Gandhara Kingdom.[1]

Ancient history

Alexander's conquests

In the spring of 327 BC Alexander the Great crossed the Indian Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and advanced to Nicaea, where Omphis, king of Taxila and other chiefs joined him. Alexander then dispatched part of his force through the valley of the Kabul River, while he himself advanced into Bajaur and Swat with his light troops.[9] Craterus was ordered to fortify and repopulate Arigaion, probably in Bajaur, which its inhabitants had burnt and deserted. Having defeated the Aspasians, from whom he took 40,000 prisoners and 230,000 oxen, Alexander crossed the Gouraios (Panjkora) and entered the territory of the Assakenoi and laid siege to Massaga, which he took by storm. Ora and Bazira (possibly Bazar) soon fell. The people of Bazira fled to the rock Aornos, but Alexander made Embolima (possibly Amb) his base, and attacked the rock from there, which was captured after a desperate resistance. Meanwhile, Peukelaotis (in Hashtnagar, 17 miles (27 km) north-west of Peshawar) had submitted, and Nicanor, a Macedonian, was appointed satrap of the country west of the Indus.[10]

Mauryan rule

Mauryan rule began with Chandragupta Maurya displacing the Nanda Empire, establishing the Mauryan Empire. A while after, Alexander's general Seleucus had attempted to once again invade the subcontinent from the Khyber pass hoping to take lands that Alexander had conquered, but never fully absorbed into this empire. Seleucus was defeated and the lands of Aria, Arachosia, Gandhara, and Gedrosia were ceded to the Mauryans in exchange for a matrimonial alliance and 500 elephants. With the defeat of the Greeks, the land was once more under Hindu rule.[11] Chandragupta's son Bindusara further expanded the empire. However, it was Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka, who converted to Buddhism and made it the official state religion in Gandhara and also Pakhli, the modern Hazara, as evidenced by rock-inscriptions at Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra.[10]

After Ashoka's death the Mauryan empire fell to pieces, just as in the west the Seleucid power was waning.

Indo-Greeks

The Indo-Greek king Menander I (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming king shortly after his victory.

His empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, Strato II, disappeared around 10 CE. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, fled from the Yuezhi invasion of Bactria and relocated to Gandhara, pushing the Indo-Greeks east of the Jhelum River. The last known Indo-Greek ruler was Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, mentioned on a 1st-century CE signet ring, bearing the Kharoṣṭhī inscription "Su Theodamasa" ("Su" was the Greek transliteration of the Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah" or "King")).

It is during this period that the fusion of Hellenistic and South Asian mythological, artistic and religious elements becomes most apparent, especially in the region of Gandhara.[13]

Local Greek rulers still exercised a feeble and precarious power along the borderland, but the last vestige of the Greco-Indian rulers were finished by a people known to the old Chinese as the Yeuh-Chi.[10]

Indo-Scythian Kingdom

The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from Central Asia into South Asia from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. The first Indo-Scythian king Maues established Saka hegemony by conquering Indo-Greek territories.[14] The power of the Saka rulers declined after the defeat to Chandragupta II of the Gupta Empire in the 4th century.[15]

Indo-Parthian Kingdom

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty, named after its first ruler Gondophares. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held Taxila (in the present Punjab province of Pakistan) as their residence, but during their last few years of existence the capital shifted between Kabul and Peshawar. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the Arsacid dynasty, but they probably belonged to a wider groups of Iranic tribes who lived east of Parthia proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the title Gondophares, which means "Holder of Glory", were even related.

Kushan Empire

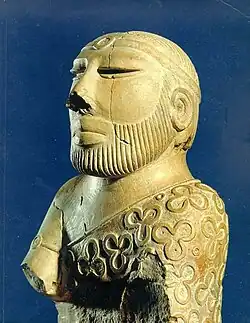

The Yuezhi nomads had driven the Sakas from the highlands of Central Asia, and were themselves forced southwards by the nomadic Xiongnu. One group, known as the Kushan, took the lead, and its chief, Kadphises I, seized vast territories extending south to the Kabul valley. His son Kadphises II conquered North-Western India, which he governed through his generals. His immediate successors were the fabled Buddhist kings: Kanishka, Huvishka, and Vasushka or Vasudeva, of whom the first reigned over a territory which extended as far east as Benares, far south as Malwa, and also including Bactria and the Kabul valley.[10][16] Their dates are still a matter of dispute, but it is beyond question that they reigned early in the Christian era. To this period may be ascribed the fine statues and bas-reliefs found in Gandhara and Udyana. Under Huvishka's successor, Vasushka, the dominions of the Kushan kings shrank.[16]

Turk and Hindu Shahis

The Turk Shahis ruled Gandhara until 870, when they were overthrown by the Hindu Shahis. The Hindu Shahis are believed to belong to the Uḍi/Oḍi tribe, namely the people of Oddiyana in Gandhara.[18][19]

The first king Kallar had moved the capital into Udabandhapura from Kabul, in the modern village of Hund for its new capital.[20][21][22][23] At its zenith, the kingdom stretched over the Kabul Valley, Gandhara and western Punjab under Jayapala.[2] Jayapala saw a danger in the consolidation of the Ghaznavids and invaded their capital city of Ghazni both in the reign of Sebuktigin and in that of his son Mahmud, which initiated the Muslim Ghaznavid and Hindu Shahi struggles.[24] Sebuk Tigin, however, defeated him, and he was forced to pay an indemnity.[24] Jayapala defaulted on the payment and took to the battlefield once more.[24] Jayapala however, lost control of the entire region between the Kabul Valley and Indus River.[25]

However, the army was defeated in battle against the western forces, particularly against the Mahmud of Ghazni.[25] In the year 1001, soon after Sultan Mahmud came to power and was occupied with the Qarakhanids north of the Hindu Kush, Jaipal attacked Ghazni once more and upon suffering yet another defeat by the powerful Ghaznavid forces, near present-day Peshawar. After the Battle of Peshawar, he died because of regretting as his subjects brought disaster and disgrace to the Shahi dynasty.[24][25]

Jayapala was succeeded by his son Anandapala,[24] who along with other succeeding generations of the Shahiya dynasty took part in various unsuccessful campaigns against the advancing Ghaznvids but were unsuccessful. The Hindu rulers eventually exiled themselves to the Kashmir Siwalik Hills.[25]

Medieval period

Ghaznavids

In 977, Sabuktagin founded the dynasty of the Ghaznavids. In 986 he raided the Indian frontier, and in 988 defeated Jaipal with his allies at Laghman. Soon afterwards he took control of the country as far as the Indus, placing a governor of his own at Peshawar. Mahmud of Ghazni, Sabuktagin's son, having secured the throne of Ghazni, again defeated Jayapala in his first raid into India (1001), Battle of Peshawar, and in a second expedition defeated Anandpal (1006), both near Peshawar. He also (1024 and 1025) raided the Pashtuns.[16] Over time, Mahmud of Ghazni had pushed further into the subcontinent, as far as east as modern day Agra. During his campaigns, many Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries had been looted and destroyed, as well as many people being forcibly converted into Islam.[26] Local Pashtun and Dardic tribes converted to Islam, while retaining some of the pre-Islamic Hindu-Buddhist and Animist local traditions such as Pashtunwali.[27] In 1179, Muhammad of Ghor took Peshawar, capturing Lahore from Khusru Malik two years later.

Delhi sultanate

Following the invasion by the Ghurids, five unrelated heterogeneous dynasties ruled over the Delhi Sultanate sequentially: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–1290), the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414), the Sayyid dynasty (1414–1451), and the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526).[28]

Meanwhile, the Pashtuns now appeared as a political factor. At the close of the fourteenth century they were firmly established in their present-day demographics south of Kohat, and in 1451 Bahlol Lodi's accession to the throne of Delhi gave them a dominant position in Northern India. Yusufzai tribes from the Kabul and Jalalabad valleys began migrating to the Valley of Peshawar beginning in the 15th century,[29] and displaced the Swatis of the Bhittani confederation and Dilazak Pashtun tribes across the Indus River to Hazara Division.[29]

Early modern history

Mughal empire

Mughal suzerainty over the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region was partially established after Babar, the founder of the Mughal Empire, invaded the region in 1505 CE via the Khyber Pass. The Mughal Empire noted the importance of the region as a weak point in their empire's defenses,[30] and determined to hold Peshawar and Kabul at all cost against any threats from the Uzbek Shaybanids.[30]

He was forced to retreat westwards to Kabul but returned to defeat the Lodis in July 1526, when he captured Peshawar from Daulat Khan Lodi,[31] though the region was never considered to be fully subjugated to the Mughals.[29]

Under the reign of Babar's son, Humayun, a direct Mughal rule was briefly challenged with the rise of the Pashtun Emperor, Sher Shah Suri, who began construction of the famous Grand Trunk Road – which links Kabul, Afghanistan with Chittagong, Bangladesh over 2000 miles to the east. Later, local rulers once again pledged loyalty to the Mughal emperor.

Yusufzai tribes rose against Mughals during the Yusufzai Revolt of 1667,[30] and engaged in pitched-battles with Mughal battalions in Peshawar and Attock.[30] Afridi tribes resisted Aurangzeb rule during the Afridi Revolt of the 1670s.[30] The Afridis massacred a Mughal battalion in the Khyber Pass in 1672 and shut the pass to lucrative trade routes.[32] Following another massacre in the winter of 1673, Mughal armies led by Emperor Aurangzeb himself regained control of the entire area in 1674,[30] and enticed tribal leaders with various awards in order to end the rebellion.[30]

Referred to as the "Father of Pashto Literature" and hailing from the city of Akora Khattak, the warrior-poet Khushal Khan Khattak actively participated in the revolt against the Mughals and became renowned for his poems that celebrated the rebellious Pashtun warriors.[30]

On 18 November 1738, Peshawar was captured from the Mughal governor Nawab Nasir Khan by the Afsharid armies during the Persian invasion of the Mughal Empire under Nader Shah.[33][34]

Durrani Empire

The area fell subsequently under the rule of Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Durrani Empire,[35] following a grand nine-day long assembly of leaders, known as the loya jirga.[36] In 1749, the Mughal ruler was induced to cede Sindh, the Punjab region and the important trans Indus River to Ahmad Shah in order to save his capital from the Durrani attack.[37] Ahmad Shah invaded the remnants of the Mughal Empire a third time, and then a fourth, consolidating control over the Kashmir and Punjab regions. In 1757, he captured Delhi and sacked Mathura,[38] but permitted the Mughal dynasty to remain in nominal control of the city as long as the ruler acknowledged Ahmad Shah's suzerainty over Punjab, Sindh, and Kashmir. Leaving his second son Timur Shah to safeguard his interests, Ahmad Shah left India to return to Afghanistan.

Their rule was interrupted by a brief invasion of the Hindu Marathas, who ruled over the region following the 1758 Battle of Peshawar for eleven months till early 1759 when the Durrani rule was re-established.[39]

Under the reign of Timur Shah, the Mughal practice of using Kabul as a summer capital and Peshawar as a winter capital was reintroduced,[29][40] Peshawar's Bala Hissar Fort served as the residence of Durrani kings during their winter stay in Peshawar.

Mahmud Shah Durrani became king, and quickly sought to seize Peshawar from his half-brother, Shah Shujah Durrani.[41] Shah Shujah was then himself proclaimed king in 1803, and recaptured Peshawar while Mahmud Shah was imprisoned at Bala Hissar fort until his eventual escape.[41] In 1809, the British sent an emissary to the court of Shah Shujah in Peshawar, marking the first diplomatic meeting between the British and Afghans.[41] Mahmud Shah allied himself with the Barakzai Pashtuns, and amassed an army in 1809, and captured Peshawar from his half-brother, Shah Shujah, establishing Mahmud Shah's second reign,[41] which lasted under 1818.

Sikh Empire

Ranjit Singh invaded Peshawar in 1818 and captured it from the Durrani Empire. The Sikh Empire based in Lahore did not immediately secure direct control of the Peshawar region, but rather paid nominal tribute to Jehandad Khan of Khattak, who was nominated by Ranjit Singh to be ruler of the region.

After Ranjit Singh's departure from the region, Khattak's rule was undermined and power seized by Yar Muhammad Khan. In 1823, Ranjit Singh returned to capture Peshawar, and was met by the armies of Azim Khan at Nowshera. Following the Sikh victory at the Battle of Nowshera, Ranjit Singh re-captured Peshawar. Rather than re-appointing Jehandad Khan of Khattak, Ranjit Singh selected Yar Muhammad Khan to once again rule the region.

The Sikh Empire annexed the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region following advances from the armies of Hari Singh Nalwa. An 1835 attempt by Dost Muhammad Khan to re-occupy Peshawar failed when his army declined to engage in combat with the Dal Khalsa. Dost Muhammad Khan's son, Mohammad Akbar Khan engaged with Sikh forces the Battle of Jamrud of 1837, and failed to recapture it.

During Sikh rule, an Italian named Paolo Avitabile was appointed an administrator of Peshawar, and is remembered for having unleashed a reign of fear there. The city's famous Mahabat Khan, built in 1630 in the Jeweler's Bazaar, was badly damaged and desecrated by the Sikhs, who also rebuilt the Bala Hissar fort during their occupation of Peshawar.

British Raj

.jpg.webp)

British East India Company defeated the Sikhs during the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, and incorporated small parts of the region into the Province of Punjab. While Peshawar was the site of a small revolt against British during the Mutiny of 1857, local Pashtun tribes throughout the region generally remained neutral or supportive of the British as they detested the Sikhs,[42] in contrast to other parts of British India which rose up in revolt against the British. However, British control of parts of the region was routinely challenged by Wazir tribesmen in Waziristan and other Pashtun tribes, who resisted any foreign occupation until Pakistan was created. By the late 19th century, the official boundaries of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region still had not been defined as the region was still claimed by the Kingdom of Afghanistan. It was only in 1893 The British demarcated the boundary with Afghanistan under a treaty agreed to by the Afghan king, Abdur Rahman Khan, following the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[43] Several princely states within the boundaries of the region were allowed to maintain their autonomy under the terms of maintaining friendly ties with the British. As the British war effort during World War One demanded the reallocation of resources from British India to the European war fronts, some tribesmen from Afghanistan crossed the Durand Line in 1917 to attack British posts in an attempt to gain territory and weaken the legitimacy of the border. The validity of the Durand Line, however, was re-affirmed in 1919 by the Afghan government with the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi,[44] which ended the Third Anglo-Afghan War – a war in which Waziri tribesmen allied themselves with the forces of Afghanistan's King Amanullah in their resistance to British rule. The Wazirs and other tribes, taking advantage of instability on the frontier, continued to resist British occupation until 1920 – even after Afghanistan had signed a peace treaty with the British.

British campaigns to subdue tribesmen along the Durand Line, as well as three Anglo-Afghan wars, made travel between Afghanistan and the densely populated heartlands of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa increasingly difficult. The two regions were largely isolated from one another from the start of the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1878 until the start of World War II in 1939 when conflict along the Afghan frontier largely dissipated. Concurrently, the British continued their large public works projects in the region, and extended the Great Indian Peninsula Railway into the region, which connected the modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region to the plains of India to the east. Other projects, such as the Attock Bridge, Islamia College University, Khyber Railway, and establishment of cantonments in Peshawar, Kohat, Mardan, and Nowshera further cemented British rule in the region. In 1901, the British carved out the northwest portions of Punjab Province to create the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), which was renamed "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa" in 2010.[45]

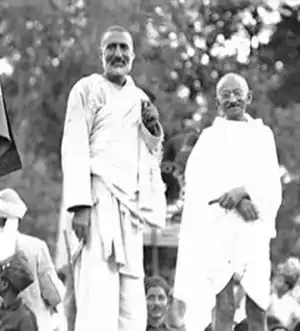

During this period, North-West Frontier Province was a "scene of repeated outrages on Hindus."[46] During the independence period there was a Congress-led ministry in the province, which was led by secular Pashtun leaders, including Bacha Khan, who preferred joining India instead of Pakistan. The secular Pashtun leadership was also of the view that if joining India was not an option then they should espouse the cause of an independent ethnic Pashtun state rather than Pakistan.[47] In June 1947, Mirzali Khan, Bacha Khan, and other Khudai Khidmatgars declared the Bannu Resolution, demanding that the Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan composing all Pashtun majority territories of British India, instead of being made to join the new state of Pakistan. However, the British Raj refused to comply with the demand of this resolution, as their departure from the region required regions under their control to choose either to join India or Pakistan, with no third option.[48][49] By 1947 Pashtun nationalists were advocating for a united India, and no prominent voices advocated for a union with Afghanistan.[50][51]

The secular stance of Bacha Khan had driven a wedge between the ulama of the otherwise pro-Congress (and pro-Indian unity) Jamiat Ulema Hind (JUH) and Bacha Khan's Khudai Khidmatgars.

There were other tensions in the area as well, particularly those that involved agitations by Pashtun tribesmen against the Imperial government. For example, in 1936, a British Indian court ruled against the marriage of a Hindu girl allegedly converted to Islam in Bannu, after the girl's family filed a case of abduction and forced conversion.[52] The ruling was based on the fact that the girl was a minor and was asked to make her decision of conversion and marriage after she reaches the age of majority, till then she was asked to live with a third party.[52] After the girl's family filed a case, the court ruled in the family's favor, angering the local Muslims who had later gone on to lead attacks against the Bannu Brigade.[52]

Such controversies stirred up anti-Hindu sentiments amongst the province's Muslim population.[53] By 1947 the majority of the ulama in the province began supporting the Muslim League's idea of Pakistan.[54]

Immediately prior to 1947 Partition of India, the British held a referendum in the NWFP to allow voters to choose between joining India or Pakistan. The polling began on 6 July 1947 and the referendum results were made public on 20 July 1947. According to the official results, there were 572,798 registered voters, out of which 289,244 (99.02%) votes were cast in favor of Pakistan, while 2,874 (0.98%) were cast in favor of India. The Muslim League declared the results as valid since over half of all eligible voters backed the merger with Pakistan.[55]

The then Chief Minister Dr. Khan Sahib, along with his brother Bacha Khan and the Khudai Khidmatgars, boycotted the referendum, citing that it did not have the options of the NWFP becoming independent or joining Afghanistan.[56][57]

Their appeal for boycott had an effect, as according to an estimate, the total turnout for the referendum was 15% lower than the total turnout in the 1946 elections,[58] although over half of all eligible voters backed merger with Pakistan.[55]

Bacha Khan pledged allegiance to the new state of Pakistan in 1947, and thereafter abandoned his goals of an independent Pashtunistan and a united India in favor of supporting increased autonomy for the NWFP within Pakistan.[42] He was subsequently arrested several times for his opposition to the strong centralized rule.[59] He later claimed that "Pashtunistan was never a reality". The idea of Pashtunistan never helped Pashtuns and it only caused suffering for them. He further claimed that the "successive governments of Afghanistan only exploited the idea for their own political goals".[60]

Post-independence

There had been tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan ever since Afghanistan voted against Pakistan's inclusion in the United Nations in 1948.[61] After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Afghanistan was the sole member of the United Nations to vote against Pakistan's accession to the UN because of Kabul's claim to the Pashtun territories on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line.[62] Afghanistan's loya jirga of 1949 declared the Durand Line invalid. This led to border tensions with Pakistan. Afghanistan's governments have periodically refused to recognize Pakistan's inheritance of British treaties regarding the region.[62] As had been agreed to by the Afghan governments following the Second Anglo-Afghan War,[63] and after the treaty ending Third Anglo-Afghan War,[64] no option was available to cede the territory to the Afghans, even though Afghanistan continued to claim the entire region as it was part of the Durrani Empire prior the conquest of the region by the Sikhs in 1818.[65]

During the 1950s, Afghanistan supported the Pushtunistan Movement, a secessionist movement that failed to gain substantial support amongst the tribes of the North-West Frontier Province. Afghanistan's refusal to recognize the Durrand Line, and its subsequent support for the Pashtunistan Movement has been cited as the main cause of tensions between the two countries that have existed since Pakistan's independence.[66]

After the Afghan-Soviet War, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has become one of the areas of top focus for the War against Terror. The province has been reported to struggle with the issues of crumbling schools, non-existent healthcare, and lack of any sound infrastructure while areas such as Islamabad and Rawalpindi receive priority funding.[67]

In 2010 the name of the province changed to "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". Protests arose among the locals of the Hazara division due to this name change, as they began to demand their own province.[68] Seven people were killed and 100 injured in protests on 11 April 2011.[68]

References

-

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, p.120: "In addition to being a center of religion for Buddhists, as well as Hindus, Taxila was a thriving center for art, culture, and learning."

- Srinivasan, Doris Meth (2008). "Hindu Deities in Gandharan art," in Gandhara, The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monasteries, and Paradise, pp.130–143: "Gandhara was not cut off from the heartland of early Hinduism in the Gangetic Valley. The two regions shared cultural and political connections and trade relations and this facilitated the adoption and exchange of religious ideas. [...] It is during the Kushan Era that flowering of religious imagery occurred. [...] Gandhara often introduced its own idiosyncratic expression upon the Buddhist and Hindu imagery it had initially come in contact with."

- Blurton, T. Richard (1993). Hindu Art, Harvard University Press: "The earliest figures of Shiva which show him in purely human form come from the area of ancient Gandhara" (p.84) and "Coins from Gandhara of the first century BC show Lakshmi [...] four-armed, on a lotus." (p.176)

- (Wynbrandt 2009, pp. 52–54)

- (Princeton Roadmap to Regents, p. 80)

- "Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith".

- Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1997). A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-81-208-0095-3.

- Kulke, Professor of Asian History Hermann; Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Warikoo, K. (2004). Bamiyan: Challenge to World Heritage. Third Eye. ISBN 978-81-86505-66-3.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4.

- (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 148)

- (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 149)

- (Faber and Faber, pp. 52–53)

- "The Buddha accompanied by Vajrapani, who has the characteristics of the Greek Heracles" Description of the same image on the cover page in Stoneman, Richard (8 June 2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-691-21747-5. Also "Herakles found an independent life in India in the guise of Vajrapani, the bearded, club-wielding companion of the Buddha" in Stoneman, Richard (8 June 2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-691-21747-5.

- en:Greco-Buddhist_art, oldid 878583324

- The Grandeur of Gandhara, Rafi-us Samad, Algora Publishing, 2011, p.64-67

- Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar p. 234

- (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 150)

- Rehman 1976, p. 187 and Pl. V B., "the horseman is shown wearing a turban-like head-gear with a small globule on the top".

- Rahman, Abdul (2002). "New Light on the Khingal, Turk and the Hindu Sahis" (PDF). Ancient Pakistan. XV: 37–42.

The Hindu Śāhis were therefore neither Bhattis, or Janjuas, nor Brahmans. They were simply Uḍis/Oḍis. It can now be seen that the term Hindu Śāhi is a misnomer and, based as it is merely upon religious discrimination, should be discarded and forgotten. The correct name is Uḍi or Oḍi Śāhi dynasty.

- Meister, Michael W. (2005). "The Problem of Platform Extensions at Kafirkot North" (PDF). Ancient Pakistan. XVI: 41–48.

Rehman (2002: 41) makes a good case for calling the Hindu Śāhis by a more accurate name, "Uḍi Śāhis".

- The Shahi Afghanistan and Punjab, 1973, pp 1, 45–46, 48, 80, Dr D. B. Pandey; The Úakas in India and Their Impact on Indian Life and Culture, 1976, p 80, Vishwa Mitra Mohan – Indo-Scythians; Country, Culture and Political life in early and medieval India, 2004, p 34, Daud Ali.

- Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1954, pp 112 ff; The Shahis of Afghanistan and Punjab, 1973, p 46, Dr D. B. Pandey; The Úakas in India and Their Impact on Indian Life and Culture, 1976, p 80, Vishwa Mitra Mohan – Indo-Scythians.

- India, A History, 2001, p 203, John Keay.

- Sehrai, Fidaullah (1979). Hund: The Forgotten City of Gandhara, p. 2. Peshawar Museum Publications New Series, Peshawar.

- P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977), The Cambridge history of Islam, Cambridge University Press, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8,

... Jaypala of Waihind saw danger in the consolidation of the kingdom of Ghazna and decided to destroy it. He therefore invaded Ghazna, but was defeated ...

- Ferishta's History of Dekkan from the first Mahummedan conquests(etc). Shrewsbury [Eng.] : Printed for the editor by J. and W. Eddowes. 1794 – via Internet Archive.

- (Wynbrandt 2009, pp. 52–55)

- (Tomsen 2013, p. 56)

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 68–102. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 9789004153882. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521566032. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Henry Miers, Elliot (2013) [1867]. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108055871.

- Richards, John F. (1996), "Imperial expansion under Aurangzeb 1658–1869. Testing the limits of the empire: the Northwest.", The Mughal Empire, New Cambridge history of India: The Mughals and their contemporaries, vol. 5 (illustrated, reprint ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 170–171, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2

- Sharma, S.R. (1999). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material, Volume 3. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788171568192. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Nadiem, Ihsan H. (2007). Peshawar: heritage, history, monuments. Sang-e-Meel. ISBN 9789693519716.

- Alikuzai, Hamid Wahed (October 2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes, Volume 14. Trafford. ISBN 9781490714417. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Siddique, Abubakar (2014). The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Hurst. ISBN 9781849044998.

- Meredith L. Runion The History of Afghanistan pp 69 Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 0313337985

- "Rivalries in India", C.C. Davies, The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. VII The Old Regime 1713–63, ed. J.O. Lindsay, (Cambridge University Press, 1988), 564.

- Schofield, Victoria, "Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia", London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks (2003), page 47

- Hanifi, Shah (11 February 2011). Connecting Histories in Afghanistan: Market Relations and State Formation on a Colonial Frontier. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7777-3. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

Timur Shah transferred the Durrani capital from Qandahar during the period of 1775 and 1776. Kabul and Peshawar then shared time as the dual capital cities of Durrani, the former during the summer and the latter during the winter season.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

- "KP Historical Overview". Humshehri. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Robson, Crisis on the Frontier pp. 136–7

- "NWFP to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". Blog.travel-culture.com. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Elst, Koenraad (2018). "70 (b)". Why I killed the Mahatma: Uncovering Godse's defence. New Delhi : Rupa, 2018.

- Pande, Aparna (2011). Explaining Pakistan's Foreign Policy: Escaping India. Taylor & Francis. p. 66. ISBN 9781136818943.

At Independence there was a Congress-led ministry in the North West Frontier...The Congress-supported government of the North West Frontier led by the secular Pashtun leaders, the Khan brothers, wanted to join India and not Pakistan. If joining India was not an option, then the secular Pashtun leaders espoused the cause of Pashtunistan: an ethnic state for Pashtuns.

- Ali Shah, Sayyid Vaqar (1993). Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (ed.). Afghanistan and the Frontier. University of Michigan: Emjay Books International. p. 256.

- H Johnson, Thomas; Zellen, Barry (2014). Culture, Conflict, and Counterinsurgency. Stanford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780804789219.

- Harrison, Selig S. "Pakistan: The State of the Union" (PDF). Center for International Policy. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Singh, Vipul (2008). The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson. p. 65. ISBN 9788131717530.

- Yousef Aboul-Enein; Basil Aboul-Enein (2013). The Secret War for the Middle East. Naval Institute Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1612513096.

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 55. JSTOR 27755911.

The stance of the central JUH was pro-Congress, and accordingly the JUS supported the Congressite Khudai Khidmatgars through to the elections of 1937. However the secular stance of Ghaffar Khan, leader of the Khudai Khidmatgars, disparaging the role of religion in government and social leadership, was driving a wedge between the ulama of the JUS and the Khudai Khidmatgars, irrespective of the commitments of mutual support between the JUH and Congress leaderships. In trying to highlight the separateness and vulnerability of Muslims in a religiously diverse public space, the directives of the NWFP ulama began to veer away from simple religious injunctions to take on a communalist tone. The ulama highlighted 'threats' posed by Hindus to Muslims in the province. Accusations of improper behaviour and molestation of Muslim women were levelled against 'Hindu shopkeepers' in Nowshera. Sermons given by two JUS-connected maulvis in Nowshera declared the Hindus the 'enemies' of Islam and Muslims. Posters were distributed in the city warning Muslims not to buy or consume food prepared and sold by Hindus in the bazaars. In 1936, a Hindu girl was abducted by a Muslim in Bannu and then married to him. The government demanded the girl's return, But popular Muslim opinion, supported by a resolution passed by the Jamiyatul Ulama Bannu, demanded that she stay, stating that she had come of her free will, had converted to Islam, and was now lawfully married and had to remain with her husband. Government efforts to retrieve the girl led to accusations of the government being anti-Muslim and of encouraging apostasy, and so stirred up strong anti-Hindu sentiment across the majority Muslim NWFP.

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 57–58. JSTOR 27755911.

By 1947 the majority of NWFP ulama supported the Muslim League idea of Pakistan. Because of the now long-standing relations between JUS ulama and the Muslim League, and the strong communalist tone in the NWFP, the move away from the pro-Congress and anti-Pakistan party line of the central JUH to interest and participation in the creation of Pakistan by the NWFP Deobandis was not a dramatic one.

- Jeffrey J. Roberts (2003). The Origins of Conflict in Afghanistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 108–109. ISBN 9780275978785. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Karl E. Meyer (5 August 2008). The Dust of Empire: The Race For Mastery In The Asian Heartland. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9780786724819. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "Was Jinnah democratic? — II". Daily Times. 25 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Electoral History of NWFP" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- Abdul Ghaffar Khan(1958) Pashtun Aw Yoo Unit. Peshawar.

- "Everything in Afghanistan is done in the name of religion: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan". India Today. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- (Kiessling 2016, p. 8)

- Frédéric Grare (October 2006). "Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations in the Post-9/11 Era" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- Barthorp, Michael (2002). Afghan Wars and the North-West Frontier, 1839–1947. Cassell. pp. 85–90. ISBN 978-0-304-36294-3.

- Barthorp, Michael (2002). Afghan Wars and the North-West Frontier, 1839–1947. Cassell. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-304-36294-3.

- Hyman, Anthony (2002). "Nationalism in Afghanistan". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 34 (2): 299–315. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 3879829.

"Greater Afghanistan," an irredentist vision based on the extensive empire conquered by Ahmad Shah Durrani.

- "'Pashtunistan' Issues Linger Behind Row". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Underhill, Natasha (2014). Countering Global Terrorism and Insurgency: Calculating the Risk of State Failure in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 195–121. ISBN 978-1-349-48064-7.

- "Anti-Pakhtunkhwa protest claims 7 lives in Abbottabad". The Statesmen. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

Sources

- Roadmap to the Regents: Global History and Geography. Princeton. 2003. ISBN 9780375763120.

- West, Barbara (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19– Imperial Gazetteer of India". Digital South Asia Library. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Bhattacharya, Avijeet. Journeys on the Silk Road Through Ages. Zorba Publishers.

- "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – province, Pakistan". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Docherty, Patty (2007). The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-1-4027-5696-2.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. New York: Infobase Publishing.

- Wink, Andre. Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. E.J Brill.

- P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge history of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29137-2.

- Nalwa, Vanit (2009). Hari Singh Nalwa – Champion of Khalsaji. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-785-5.

- Kazi, Sarwar (20 April 2002). "Qissa Khwani's tale of tear and blood". The Statesman.

- The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1753-0.

- Meyer, Karl E. (5 August 2008). The Dust Of Empire: The Race For Mastery In The Asian Heartland. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9780786724819 – via Google Books.

- Jeffrey J. Roberts (2003). The Origins of Conflict in Afghanistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275978785. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Kiessling, Hein (2016). Faith, Unity, Discipline. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1849045179.

- Gupta, G.S (1999). India:From Indus Valley Civilisation to Mauryas. Concept Publishers. ISBN 81-7022-763-1.

- Comrie, Bernard (1990). The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press.

- Ancient Pakistan: Volume 3. University of Peshawar Dept. of Archaeology. 1967.

- Bhandarkar, D.R (1967). Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture.

- Aboul-Enein, Yousef; Aboul-Enein, Basil (2013). The Secret War for the Middle East. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1612513096.

- Tomsen, P. (2013). The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-412-3. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- Rehman, Abdur (January 1976). The Last Two Dynasties of the Sahis: An analysis of their history, archaeology, coinage and palaeography (Thesis). Australian National University.