History of Botswana

The Batswana, a term also used to denote all citizens of Botswana, refers to the country's major ethnic group (called the Tswana in Southern Africa). Prior to European contact, the Batswana lived as herders and farmers under tribal rule.[1]

| History of Botswana |

|---|

|

| See also |

Before European contact

The Tsodilo Hills site in north-west Botswana has been apparently continuously inhabited since 17 000 BC.[2] The forebears of today's Khoe-Kwadi, Kx’a and Tuu-speaking peoples (“Khoisan”) are thought to have lived in the area now corresponding to Botswana for many thousands of years.

In October 2019, researchers reported that Botswana was likely the region where modern humans first developed about 200,000-300,000 years ago.[3][4] Sometime between 200 and 500 AD, the Bantu-speaking people who were living in the Katanga area (today part of the DRC and Zambia) crossed the Limpopo River, entering the area today known as South Africa as part of the Bantu expansion.[5]

There were 2 broad waves of immigration to South Africa; Nguni and Sotho-Tswana. The former settled in the eastern coastal regions, while the latter settled primarily in the area known today as the Highveld—the large, relatively high central plateau of South Africa.

By 1000 AD the Bantu colonization of the eastern half of South Africa had been completed (but not Western Cape and Northern Cape, which are believed to have been inhabited by “Khoisan” peoples until Dutch colonisation). The Bantu-speaking societies were highly decentralized, organized on a basis of enlarged clans (kraals) headed by a chief, who owed a hazy allegiance to the nation's head chief.

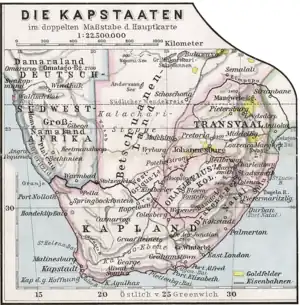

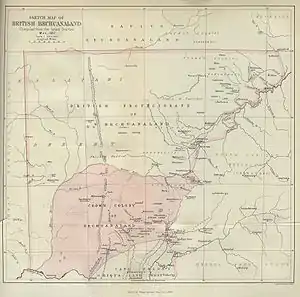

Bechuanaland Protectorate

In the late 19th century, hostilities broke out between the Shona inhabitants of Botswana and Ndebele tribes who were migrating into the territory from the Kalahari Desert.[6] Tensions also escalated with the Boer settlers from the Transvaal. To block Boer and German expansionism the British Government on 31 March 1885 put "Bechuanaland" under its protection. The northern territory remained under direct administration as the Bechuanaland Protectorate and is today's Botswana, while the southern territory became British Bechuanaland which ten years later became part of the Cape Colony and is now part of the northwest province of South Africa; the majority of Setswana-speaking people today live in South Africa. The Tati Concessions Land, formerly part of the Matabele kingdom, was administered from the Bechuanaland Protectorate after 1893, to which it was formally annexed in 1911.

To safeguard the integrity of the Protectorate against the perceived threats from the British South Africa Company and Southern Rhodesia, the three Batswana leaders Khama III, Bathoen I, and Sebele I travelled to London in 1895 to ask Joseph Chamberlain and Queen Victoria for assurances.[7]

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910 out of the main British colonies in the region, the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana), Basutoland (now Lesotho), and Swaziland (now Eswatini) (the "High Commission Territories") were not included, but provision was made for their later incorporation. However, a vague undertaking was given to consult their inhabitants, and although successive South African governments sought to have the territories transferred, Britain kept delaying, and it never occurred. The election of the National Party government in 1948, which instituted apartheid, and South Africa's withdrawal from the Commonwealth in 1961, ended any prospect of incorporation of the territories into South Africa.[8]

An expansion of British central authority and the evolution of tribal government resulted in the 1920 establishment of two advisory councils representing Africans and Europeans. Proclamations in 1934 regularized tribal rule and powers. A European-African advisory council was formed in 1951, and the 1961 constitution established a consultative legislative council.[9]

Following the British entry into World War II, the decision was taken to draw recruits from the High Commission Territories (HTC) of Swaziland, Basutoland and Bechuanaland. Black citizens from the HTC were to be recruited into the African Auxiliary Pioneer Corps (AAPC) labor unit due to Afrikaner opposition to armed black units.[10] Mobilization for the AAPC was launched in late July 1941 and by October 18,000 personnel had arrived in the Middle East.[11] The AAPC performed a wide range of manual labor, providing logistical support to the Allied war effort during the North African, Dodecanese and Italian campaigns.[12][13] During the Italian campaign some AAPC relieved British field artillery units of their duty.[14]

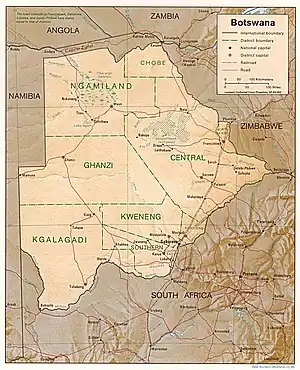

Independent Botswana

In June 1966, Britain accepted proposals for democratic self-government in Botswana.[15] The seat of government was moved from Mafeking, South Africa, to newly established Gaborone in 1965. The 1965 constitution led to the first general elections and to independence on 30 September 1966. Seretse Khama, a leader in the independence movement and the legitimate claimant to the Ngwato chiefship, was elected as the first president, re-elected twice, and died in office in 1980. The presidency passed to the sitting vice president, Ketumile Masire, who was elected in his own right in 1984 and re-elected in 1989 and 1994. Masire retired from office in 1998. The presidency passed to the sitting vice president, Festus Mogae, who was elected in his own right in 1999 and re-elected in 2004. In April 2008, Excellency the former President Lieutenant General Dr Seretse Khama Ian Khama (Ian Khama), son of Seretse Khama the first president, succeeded to the presidency when Festus Mogae retired.[16] On 1 April 2018 Mokgweetsi Eric Keabetswe Masisi was sworn in as the 5th President of Botswana succeeding Ian Khama. He represents the Botswana Democratic Party, which has also won a majority in every parliamentary election since independence. All the previous presidents have also represented the same party.[17]

See also

Footnotes

- "Botswana". clintonwhitehouse3.archives.gov. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- "Botswana History Page 1: Brief History of Botswana". www.thuto.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- Chan, Eva, K. F.; et al. (28 October 2019). "Human origins in a southern African palaeo-wetland and first migrations". Nature. 857 (7781): 185–189. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..185C. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1714-1. PMID 31659339. S2CID 204946938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Woodward, Aylin (28 October 2019). "New Study Pinpoints The Ancestral Homeland of All Humans Alive Today". ScienceAlert.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Africa: Botswana". Q-files: The Great Illustrated Encyclopedia. Orpheus Books Limited. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "The Republic of Botswana" (PDF). The Country Woman: 9–13. February 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-03-01.

- Morton, Barry; Ramsay, Jeff (13 June 2018). Historical dictionary of Botswana. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 217. ISBN 9781538111321.

- Mugoti, Godfrey (2009). Africa (A-Z). Godfrey books. ISBN 978-1435728905.

- Africa its problems and prospects a bibliographic survey. Army Library (U.S.). September 1962. p. 262. hdl:2027/uiug.30112063978792.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Shackleton 1997, pp. 95–97.

- Sipho Simelane 1993, pp. 545–548.

- Clothier 1991.

- Shackleton 1997, pp. 215–230.

- Shackleton 1997, pp. 271–275.

- Peter Fawcus, and Alan Tilbury, Botswana: The Road to Independence (Pula Press, 2000)

- Heath-Brown, Nick (2017-02-07). The Statesman's Yearbook 2016: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-57823-8.

- "Botswana country profile". BBC News. 3 April 2018. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023.

References

- Clothier, Norman (1991). "The Erinpura: Basotho Tragedy". South African Military History Society Journal. 8 (5). ISSN 0026-4016. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Shackleton, Deborah Ann (1997). Imperial Military Policy and the Bechuanaland Pioneers and Gunners during the Second World War (PhD thesis). Indiana University. OCLC 38033601.

- Sipho Simelane, Hamilton (1993). "Labor Mobilization for the War Effort in Swaziland, 1940–1942". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 26 (3): 541–574. doi:10.2307/220478. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 220478.

Further reading

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. "An African success story: Botswana." (2002). online

- Cohen, Dennis L. "The Botswana Political Elite: Evidence from the 1974 General Election," Journal of Southern African Affairs, (1979) 4, 347–370.

- Colclough, Christopher and Stephen McCarthy. The Political Economy of Botswana: A Study of Growth and Income Distribution (Oxford University Press, 1980)

- Denbow, James & Thebe, Phenyo C. (2006). Culture and Customs of Botswana. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33178-2.

- Edge, Wayne A. and Mogopodi H. Lekorwe eds. Botswana: Politics and Society (Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik, 1998)

- Fawcus, Peter and Alan Tilbury. Botswana: The Road to Independence (Pula Press, 2000)

- Good, Kenneth. "Interpreting the Exceptionality of Botswana," Journal of Modern African Studies (1992) 30, 69–95.

- Good, Kenneth. "Corruption and Mismanagement in Botswana: A Best-Case Example?" Journal of Modern African Studies, (1994) 32, 499–521.

- Parsons, Neil. King Khama, Emperor Joe and the Great White Queen (University of Chicago Press, 1998)

- Parsons, Neil, Thomas Tlou and Willie Henderson. Seretse Khama, 1921-1980 (Bloemfontein: Macmillan, 1995)

- Samatar, Abdi Ismail. An African miracle: State and class leadership and colonial legacy in Botswana development (Heinemann Educational Books, 1999)

- Thomas Tlou & Alec Campbell, History of Botswana (Gaborone: Macmillan, 2nd edn. 1997) ISBN 0-333-36531-3

- Chirenje, J. Mutero, Church, State, and Education in Bechuanaland in the Nineteenth Century, International Journal of African Historical Studies, (1976)

- Chirenje, J. Mutero, Chief Kgama and His Times, 1835-1923