History of Guinea-Bissau

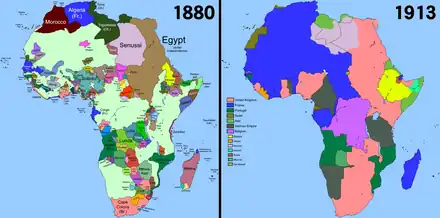

The region now known as Guinea-Bissau has been inhabited for thousands of years. In the 13th century, it became a province of the Mali Empire that later became independent as the Empire of Kaabu. The region was claimed by Portugal beginning in the 1450s. During most of this period, Portuguese control of the region was limited to a number of forts along the coast. Portugal gained full control of the mainland after the pacification campaigns of 1912–15. The offshore Bijago islands were not colonised until 1936.[1][2] After independence in 1974, the country was controlled by a single-party system until 1991. The introduction of multi-party politics in 1991, brought the first multi-party elections in 1994. A civil war broke out from 1998 to 1999.

| History of Guinea-Bissau |

|---|

.svg.png.webp)  |

| Colonial history |

| Independence struggle |

Peoples and Society

The history of the region has not been extensively documented in the archaeological record. It was populated by at least 1000 AD by hunter-gatherers, shortly followed by agriculturists using iron tools.[3]

The oldest inhabitants were the Jola, Papels, Manjaks, Balanta, and Biafada. Later the Mandinka and Fulani migrated into the region, pushing the earlier inhabitants towards the coast.[3][4]: 20 A small number of Mandinka had been resent in the region as early as the 11th century,[5]: 6 but they migrated en masse around the 13th century as Senegambia was incorporated into the Mali Empire by General Tiramakhan Troare, who founded Kaabu.[6] A process of 'Mandinkization' ensued.[5]: 6 The Fulani began arriving as early as the 12th century as semi-nomadic herders, but were not a large presence until the 15th century.[3]

The Balanta and Jola had weak or nonexistent institutions of kingship and instead put an emphasis on heads of villages and families.[4]: 64 The Mandinka, Fula, Papel, Manjak, and Biafada chiefs were vassals to kings. The customs, rites, and ceremonies varied, but nobles commanded all the major positions, including the judicial system.[4]: 66, 67, 73, 227 Social stratification was seen in the clothing and accessories of the people, in housing materials, and in transportation options.[4]: 77–8

Trade was widespread between ethnic groups. Items traded included pepper and kola nuts from the southern forests; kola nuts, iron, and iron utensils from the savannah-forest zone; salt and dried fish from the coast; and Mandinka cotton cloth.[7]: 4 The products were commonly sold at markets and fairs held weekly or every eight days, which could be attended by several thousand buyers and sellers from as far as 60 miles away. Weapons were prohibited in the marketplace, and soldiers were positioned around the area to keep order throughout the day. Sections of the market would be allocated for specific products, except for wine, which could be sold anywhere.[4]: 69–70

Pre-Colonial Kingdoms

Kaabu

Origins

Kaabu was first established as a province of Mali through the conquest of the Senegambia by a general of Sundiata Keita named Tiramakhan Traore, in the 13th century.[8] According to oral tradition, Tiramakhan Traore invaded the region to punish the Wolof king for having insulted Sundiata, and then carried on south of the River Gambia into the Casamance.[9] This initiated a migration of Mandinka into the region. By the 14th century, much of Guinea Bissau was under the administration of Mali and ruled by a farim kaabu (commander of Kaabu).[8]

Mali declined gradually, beginning in the 14th century. Formerly secure possessions in what is now Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau were cut off by the expanding power of Koli Tenguella in the early 16th century.[10] Kaabu became an independent federation of kingdoms, the most powerful western Mandinka state of the period.[5]: 13 .[11]

Society

Kaabu's ruling classes were composed of elite warriors known as the Nyancho who traced their patrilineal lineage to Tiramakhan Troare.[6]: 2 The Nyancho were a warrior culture, reputed to be excellent cavalry men and raiders.[5]: 6 The Kaabu Mansaba was seated in Kansala, today known as Gabu, in the eastern Geba region.[7]: 4 Malian imperial history was central to Kaabu culture, maintaining its major institutions and the lingua franca of Mandinka.[5]: 11 Individuals from other ethnic backgrounds often became assimilated into this dominant culture, and frequent inter-ethnic marriages assisted the process.[5]: 12

The slave trade dominated the economy, enriching the warrior classes with imported cloth, beads, metalware, and firearms.[5]: 8 Trade networks to North Africa were dominant up to the 14th century, with coastal trade with the Europeans increasing beginning in the 15th century.[7]: 3 In the 17th and 18th centuries an estimated 700 slaves left the region annually, many of them from Kaabu.[7]: 5

Decline

In the late 18th century, the rise of the Imamate of Futa Jallon to the east posed a powerful challenge to animist Kaabu. During the first half of the 19th century, civil war erupted as local Fula people sought independence.[7]: 5–6 This long-running conflict led to the 1867 Battle of Kansala. A Fula army led by Alpha Molo Balde laid siege to the earthen walls of Kansala for 11 days. The Mandinka kept the Fulani from climbing the walls for a time, but the walls were overwhelmed.[12]: 14 The Mansaba Dianke Walli, seeing that he would lose, ordered his troops to set the city's gunpowder on fire, killing the Mandinka defenders alongside most of the invading army.[13] The loss of Kansala marked the end of the Kaabu and the rise of Fuladu, though some smaller Mandinka kingdoms survived until their absorption by the Portuguese.

Biafada kingdoms

The Biafada people inhabited the area around the Rio Grande de Buba in three kingdoms: Biguba, Guinala, and Bissege.[4]: 65 The former two were important ports with significant lançado communities.[14] They were subjects of the Mandinka mansa of Kaabu.[15]

Kingdom of Bissau

According to oral tradition, the Kingdom of Bissau was founded by the son of the king of Quinara (Guinala) who moved to the area with his pregnant sister, six wives, and subjects of his father's kingdom.[16] Relations between the kingdom and the Portuguese were initially warm, but deteriorated over time.[17]

The kingdom strongly defended its sovereignty against the Portuguese 'Pacification Campaigns,' defeating them in 1891, 1894, and 1904. In 1915, the Portuguese, under the command of Officer Teixeira Pinto and warlord Abdul Injai, fully absorbed the kingdom.[18]

The Bijagos

In the Bijagos Islands, different islands were populated by people of different ethnic origins, leading to great cultural diversity in the archipelago.[4]: 24 [19]

Bijago society was warlike. Men were dedicated to boat-building and raiding the mainland, attacking the coastal peoples as well as other islands, believing that on the sea they had no king. Women cultivated land, constructed houses, and gathered food, and could choose their husbands, generally warriors with the best reputation. Successful warriors could have many wives and boats, and were entitled to one-third of the spoils of the boat from any expedition.[4]: 204–205

Bijago night raids on coastal settlements had significant impact on the societies attacked. Portuguese traders on the mainland tried to stop the raids, as they hurt the local economy, but the islanders also sold considerable numbers of slaves to the Europeans, who frequently pushed for more captives.[4]: 205 The Bijagos themselves were mostly safe from enslavement, out of reach of mainland slave raiders. Europeans avoided having them as slaves. Portuguese sources say the children made good slaves but not the adults, who were likely to commit suicide, lead rebellions aboard slave ships, or escape once reaching the New World.[4]: 218–219

European Contact

.svg.png.webp)

15th–16th centuries

The first Europeans to reach Guinea-Bissau were the Venetian explorer Alvise Cadamosto in 1455, Portuguese explorer Diogo Gomes in 1456, Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pareira in the 1480s, and Flemish explorer Eustache de la Fosse in 1479–1480.[20]: 7, 12, 13, 16 The region was known to the Portuguese as 'The Guinea of Cape Verde', and Santiago was the administrative capital and the source of most of its white settlers.[4]

Although the Portuguese authorities initially discouraged white settlement on the mainland, this prohibition was ignored by lançados and tangomãos who assimilated into indigenous culture and customs.[4]: 140 They were mainly from impoverished backgrounds, traders from Cape Verde or people exiled from Portugal, often of Jewish and/or New Christian background.[4]: 148–150 They ignored Portuguese trade regulations banning entering the region or trading without a royal licence, shipping out of unauthorised ports, or assimilating into the native community.[4]: 142 In 1520 they reduced measures against the lançados, and trade and settlements increased on the mainland populated by the Portuguese and native traders, as well some Spanish, Genoese, English, French, and Dutch.[4]: 145, 150

With the regions rivers possessing no natural harbours, the lançados and native traders navigated riverways and creeks in small boats purchased from European ships or manufactured locally by trained grumetes (native African sailors, both slave and free). The main ports were Cacheu, Bissau, and Guinala, and each river also sported trading centers such as Toubaboudougou at their furthest navigable point that traded directly with the interior for resources such as gum arabic, ivory, hides, civet, dyes, slaves, and gold.[4]: 153–160 A small number of European settlers established isolated farms along the rivers. Meanwhile, local African rulers generally refused to allow Europeans into the interior, to ensure their control of trade routes.[21]

Europeans were not accepted in all communities, with the Jolas, Balantas, and Bijagos initially hostile. The other ethnicities of the region all harboured communities of lançados, who were subject to taxation and the laws and customs of the community they lived in, including the local courts.[4]: 164–5 Disputes became increasingly frequent and serious in the late 1500s as the foreign traders sought to influence the host societies to their benefit. Under pressure from hostile locals, the Portuguese abandoned the settlement of Buguendo near Cacheu in 1580 and Guinala in 1583, where they retreated to a fort. In 1590 they built a fort at Cacheu, which the local Manjaks unsuccessfully stormed shortly after its construction.[22] These forts, poorly manned and provisioned, were unable to completely free the lançados from their responsibilities to the native monarchs, their hosts, who themselves could not kick the traders out as goods that they brought in were in high demand with the upper class.[4]: 180–184

Meanwhile, the Portuguese monopoly, always leaky, was being increasingly challenged. In 1580 the Iberian Union unified the crowns of Portugal and Spain, leading to the attack of Portuguese possessions in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde by Spain's enemies. French, Dutch, and English ships increasingly came to trade with the natives and the independent-minded lançados..[4]: 244–53

17th–18th centuries

In the early 17th century the government attempted to force all Guinean trade to go through Santiago and to promote trade and settlement on the mainland while restricting the sale of weapons to the locals. These efforts were largely unsuccessful.[4]: 243–4 With the end of the Iberian Union in 1640, King João IV attempted to restrict the Spanish trade in Guinea that had flourished for the previous 60 years. The Afro-Portuguese in Bissau, Guinala, Geba, and Cacheu swore allegiance to the Portuguese king, but were not in a position to deny the free trade that the African kings, who now saw European products as necessities, demanded. In Cacheu famine had wiped out the slave troops in charge of defending the fort, the water supply remained in Manjak hands, and the lançados (and their Africanized descendants) were no more enthused about losing customers than the locals, so Captain-Major Luis de Magalhães had no choice but to lift the embargo.[4]: 261–3

In 1641 the Conselho Ultramarino replaced de Magalhães with Gonçalo de Gamboa de Ayala. He had some success winning over local leaders and stopping Spanish ships at Cacheu. In Bissau, however, two Spanish ships entered and were afforded full protection by the King of Bissau. Ayala threatened violent repercussions, but nothing came of it. He did successfully resettle the Afro-European community of Geba to Farim northeast of Cacheu.[4]: 266–71 The Portuguese were never able to impose their monopolistic vision on the local and Afro-European traders, as the economic interests of the native leaders and Afro-European merchants never fully aligned with theirs. During this period the power of the Mali Empire in the region was dissipating, and the farim of Kaabu, the king of Kassa and other local rulers began to assert their independence.[4]: 488

In the early 1700s the Portuguese abandoned Bissau and retreated to Cacheu after the captain-major was captured and killed by the local king. They would not return until the 1750s. Meanwhile, the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company shut down in 1706.[23] For a brief period in the 1790s, the British tried to establish a foothold on Bolama.[24]

Slave trade

Guinea-Bissau was among the first regions touched by the Atlantic slave trade and, while it did not produce the same number of enslaved people as other regions, the impact was still significant.[25][21] At first slaves were mainly sent to Cape Verde and the Iberian Peninsula, with the Madeira and the Canary Islands seeing an influx at lower volumes.[4]: 186–7 In Cape Verde especially they were instrumental in developing the plantation economy, growing indigo and cotton and weaving panos cloth that became a standard currency in West Africa.[3]

From 1580 to 1640 many slaves from Guinea-Bissau were destined for the Spanish West Indies, with an average of 3000 shipped every year from Guinala alone.[4]: 278 The 17th and 18th centuries saw thousands of people taken from the region every year by Portuguese, French, and British companies. The Fula jihads and specifically the wars between the Imamate of Futa Jallon and Kaabu provided many of these.[26]

There were four main ways in which people were enslaved: as punishment for law breaking, selling themselves or relatives during famines, kidnapped by native marauders or European raiders, or as prisoners of war. Most slaves were bought by Europeans from local rulers or traders.[4]: 198–200 Every ethnicity in the region participated in the trade with the exception of the Balantas and Jolas.[4]: 208, 217 Most wars were waged for the sole purpose of capturing slaves to sell to the Europeans in exchange for imported goods, such that they resembled man-hunts more than conflicts over territory or political power.[4]: 204, 209 The nobles and kings benefited, while the common people bore the brunt of the raiding and insecurity. If a noble was captured they were likely to be released, as the captors, whoever they were, would generally accept a ransom in exchange for their freedom.[4]: 229 The relationship between kings and European traders was a partnership, with the two regularly making deals on how the trade was to be conducted, who was to be enslaved and who was not, and the prices of the slaves. Contemporary chroniclers Fernão Guerreiro and Mateo de Anguiano questioned multiple kings on their part in the slave trade, noting that they recognised the trade as evil but participated because the Europeans would buy no other goods from them.[4]: 230–4

Beginning in the late 18th century, European countries gradually began slowing and/or abolishing the slave trade. The British navy and, to a more half-hearted extent, the U.S. Navy attempted to intercept slavers off the coast of Guinea in the first half of the 19th century. This restriction of supply, however, only increased prices and intensified illegal slave-trading activity. Portugal abandoned slavery in 1869 and Brazil in 1888, but a system of contract labor replaced it that was only barely better for the workers.[26]

Colonialism

Up until the late 1800s, Portuguese control of their 'colony' outside of their forts and trading posts was a fiction. African rulers held power in the countryside, and frequent attacks and assassinations against the Portuguese marked the middle decades of the century.[27] Guinea-Bissau became the scene of increased European colonial competition beginning in the 1860s. The dispute over the status of Bolama was resolved in Portugal's favor through the mediation of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant in 1870, but French encroachment on Portuguese claims continued. In 1886 the Casamance region of what is now Senegal was ceded to them.[3]\

Attempting to shore up domestic finances and strengthen the grip on the colony, in 1891 António José Enes, Minister of Marine and Colonies, reformed tax laws and granted concessions in Guinea, mainly to foreign companies, to increase exports.[28] The modest increase in government income, however, did not defray the cost of the troops used to impose the taxes. Resistance continued throughout the area, but these reforms laid the groundwork for future military expansion.[29][30]

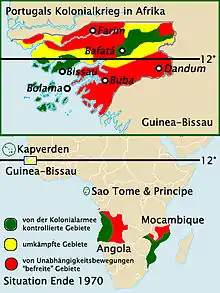

To meet the Berlin Congress standard of 'effective occupation', the Portuguese colonial government embarked on a series of 'pacification campaigns' that were mostly military failures up until the arrival of Capt. João Teixeira Pinto in 1912. Supported by a large mercenary army commanded by Senegalese fugitive Abdul Injai, he quickly and brutally crushed local resistance on the mainland. Three more bloody campaigns in 1917, 1925, and 1936 were required to 'pacify' the Bissagos Islands.[27] Portuguese Guinea remained a neglected backwater, however, with administration expenses exceeding revenue.[31] In 1951, responding to anti-colonial criticism in the United Nations, the Portuguese government rebranded all of their colonies, including Portuguese Guinea, as overseas provinces (Províncias Ultramarines).[32]

Struggle for Independence

The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) was founded in 1956 under the leadership of Amílcar Cabral. Initially committed to peaceful methods, the 1959 Pidjiguiti massacre pushed the party towards more militarized tactics, leaning heavily on the political mobilization of the peasantry in the countryside. After years of planning and preparing from their base in Conakry, the PAIGC launched the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence on 23 January 1963.[33]

Unlike guerrilla movements in other Portuguese colonies, the PAIGC rapidly extended its control over large portions of the territory. Aided by the jungle-like terrain, it had easy access to borders with neighbouring allies and large quantities of arms from Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, and left-leaning African countries. Cuba also agreed to supply artillery experts, doctors, and technicians.[34] The PAIGC even managed to acquire a significant anti-aircraft capability in order to defend itself against aerial attack. By 1973, the PAIGC was in control of many parts of Guinea, although the movement suffered a setback in January 1973 when its founder and leader Amilcar Cabral was assassinated.[35]

After Cabral's death, party leadership fell to Aristides Pereira, who would later become the first president of the Republic of Cape Verde. The PAIGC National Assembly met at Boe in the southeastern region and declared the independence of Guinea-Bissau on 24 September 1973. This was recognized by a 93–7 UN General Assembly vote in November.[36]

Independence

Following Portugal's April 1974 Carnation Revolution, it granted independence to Guinea-Bissau on 10 September 1974. Luís Cabral, Amílcar Cabral's half-brother, became President. The United States recognised Guinea Bissau's independence on 10 September 1974.[37]

In late 1980, the government was overthrown in a coup led by Prime Minister and former armed forces commander João Bernardo Vieira.[38][39]

Democracy

In 1994, 20 years after independence from Portugal, the country's first multiparty legislative and presidential elections were held. An army uprising that triggered the Guinea-Bissau Civil War in 1998, created hundreds of thousands of displaced persons. The president was ousted by a military junta on 7 May 1999. An interim government turned over power in February 2000 when opposition leader Kumba Ialá took office following two rounds of transparent presidential elections. Guinea-Bissau's transition back to democracy has been complicated by a crippled economy devastated by civil war and the military's predilection for governmental meddling.

Presidency of Kumba Ialá

Despite reports that there had been an influx of arms in the weeks leading up to the election and reports of some 'disturbances during campaigning' – including attacks on the presidential palace and the Interior Ministry by as-yet-unidentified gunmen – European monitors labelled the election as "calm and organized".[40]

In January 2000, the second round of a general election took place. The presidential election resulted in a victory for opposition leader Kumba Ialá of the Party for Social Renewal (PRS), who defeated Malam Bacai Sanhá of the ruling PAIGC. The PRS were also victorious in the National People's Assembly election, winning 38 of the 102 seats.

2003 coup

In September 2003, a military coup was conducted. The military arrested Ialá on the charge of being "unable to solve the problems".[41] After being delayed several times, legislative elections were held in March 2004. A mutiny of military factions in October 2004 resulted in the death of the head of the armed forces and caused widespread unrest.

Second presidency of João Bernardo Vieira

In June 2005, presidential elections were held for the first time since the coup that deposed Ialá. Ialá returned as the candidate for the PRS, claiming to be the legitimate president of the country. The election was won by former president João Bernardo Vieira, deposed in the 1999 coup. Vieira beat Malam Bacai Sanhá in a run-off election. Sanhá initially refused to concede, claiming that tampering and electoral fraud occurred in two constituencies including the capital, Bissau.[42]

Despite reports of arms entering the country prior to the election and some "disturbances during campaigning", including attacks on government offices by unidentified gunmen, foreign election monitors described the 2005 election overall as "calm and organized".[43]

Three years later, PAIGC won a strong parliamentary majority, with 67 of 100 seats, in the parliamentary election held in November 2008.[44] In November 2008, President Vieira's official residence was attacked by members of the armed forces, killing a guard but leaving the president unharmed.[45]

On 2 March 2009, Vieira was assassinated by what preliminary reports indicated to be a group of soldiers avenging the death of the head of joint chiefs of staff, General Batista Tagme Na Wai, who had been killed in an explosion the day before.[46] Vieira's death did not trigger widespread violence, but there were signs of turmoil in the country, according to the advocacy group Swisspeace.[47] Military leaders in the country pledged to respect the constitutional order of succession. National Assembly Speaker Raimundo Pereira was appointed as an interim president until a nationwide election on 28 June 2009.[48] It was won by Malam Bacai Sanhá of the PAIGC, against Kumba Ialá as the presidential candidate of the PRS.[49]

2012 coup

On 9 January 2012, President Sanhá died of complications from diabetes, and Pereira was again appointed as an interim president. On the evening of 12 April 2012, members of the country's military staged a coup d'état and arrested the interim president and a leading presidential candidate.[50] Former vice chief of staff, General Mamadu Ture Kuruma, assumed control of the country in the transitional period and started negotiations with opposition parties.[51][52]

Presidencies of José Mário Vaz and Umaro Sissoco Embaló

José Mário Vaz was the President of Guinea-Bissau from 2014 until 2019 presidential elections. At the end of his term, Vaz became the first elected president to complete his five-year mandate. He lost the 2019 election to Umaro Sissoco Embaló, who took office in February 2020. Embaló is the first president to be elected without the backing of the PAIGC.[53][54]

In February 2022, there was a failed coup attempt against President Embaló. According to Embaló, the coup attempt was linked to drug trafficking.[55]

See also

- Politics of Guinea-Bissau

- United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNOGBIS)

- City of Bissau history and timeline

References

- Bowman, Joye L. (1986). "Abdul Njai: Ally and Enemy of the Portuguese in Guinea-Bissau, 1895–1919". The Journal of African History. 27 (3): 463–479. doi:10.1017/S0021853700023276. S2CID 162344466.

- Corbin, Amy; Tindall, Ashley. "Bijagós Archipelago". Sacred Land Film Project. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Early history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- Rodney, Walter Anthony (May 1966). "A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545–1800" (PDF). Eprints. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Wright, Donald R (1987). "The Epic of Kalefa Saane as a guide to the Nature of Precolonial Senegambian Society-and Vice Versa" (PDF). History in Africa. 14: 287–309. doi:10.2307/3171842. JSTOR 3171842. S2CID 162851641 – via JSTOR.

- "Kaabu Oral History Project Proposal" (PDF). Archives. 1980. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Schoenmakers, Hans (1987). "Old Men and New State Structures in Guinea-Bissau". The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. 19 (25–26): 99–138. doi:10.1080/07329113.1987.10756396.

- "Kaabu Empire (aka N'Gabu/Gabu)". GlobalSecurity.org.

- Niane 1989, pp. 19.

- Barry 1998, pp. 21.

- Page, Willie F. (2005). Davis, R. Hunt (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History and Culture. Vol. III (Illustrated, revised ed.). Facts On File. p. 92.

- Sonko-Godwin, Patience (1988). Ethnic Groups of the Senegambia: A Brief History. Banjul, Gambia: Sunrise Publishers. ISBN 9983-86-000-7.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 276.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 63, 211.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 211.

- Nanque, Neemias Antonio (2016). Revoltas e resistências dos Papéis da Guiné-Bissau contra o Colonialismo Português – 1886–1915 (PDF) (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 55.

- Bowman, Joye L. (22 January 2009). "Abdul Njai: Ally and Enemy of the Portuguese in Guinea-Bissau, 1895–1919". The Journal of African History. 27 (3): 463–479. doi:10.1017/S0021853700023276. S2CID 162344466.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 52.

- Hair, P. E. H. (1994). "The Early Sources on Guinea" (PDF). History in Africa. 21: 87–126. doi:10.2307/3171882. JSTOR 3171882. S2CID 161811816 – via Cambridge University Press.

- "HISTORY OF GUINEA-BISSAU". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 74.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. xliii.

- "British Library – Endangered Archive Programme (EAP)". inep-bissau.org. 18 March 1921. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Gale Group. (2017). Guinea-Bissau. In M. S. Hill (Ed.), Worldmark encyclopedia of the nations (14th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 379–392). Gale.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 377.

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 300.

- Clarence-Smith 1975, pp. 82–3, 85.

- R Pélissier, (1989). História da Guiné: portugueses e africanos na senegambia 1841–1936 Volume II, Lisbon, Imprensa Universitária pp 25–6, 62–4.

- R E Galli & J Jones (1987). Guinea-Bissau: Politics, economics, and society, London, Pinter pp. 28–9.

- Clarence-Smith 1975, pp. 114–7.

- G. J. Bender (1978), Angola Under the Portuguese: The Myth and the Reality, Berkeley, University of California Press p.xx. ISBN 0-520-03221-7

- Lobban & Mendy 2013, pp. 289.

- El Tahri, Jihan (2007). Cuba! Africa! Revolution!. BBC Television. Event occurs at 50:00–60:0. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- Brittain, Victoria (17 January 2011). "Africa: a continent drenched in the blood of revolutionary heroes". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- United Nations General Assembly Session -1 Resolution 3061. Illegal occupation by Portuguese military forces of certain sectors of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau and acts of aggression committed by them against the people of the Republic A/RES/3061(XXVIII) 2 November 1973. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, Since 1776: Guinea-Bissau". Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Guinea Bissau - Coup and After". Economic and Political Weekly. 15 (52): 7–8. 5 June 2015.

- "Obituary: Luís Cabral". the Guardian. 7 June 2009.

- BBC News

- Smith, Brian (27 September 2003) "US and UN give tacit backing to Guinea Bissau coup" Archived 27 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Wsws.org, September 2003. Retrieved 22 June 2013

- GUINEA-BISSAU: Vieira officially declared president Archived 25 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. irinnews.org (10 August 2005).

- "Army man wins G Bissau election". BBC News. London. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- Guinea Bissau vote goes smooth amid hopes for stability. AFP via Google.com (16 November 2008). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Balde, Assimo (24 November 2008). "Coup attempt fails in Guinea-Bissau". London: The Independent UK independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Soldiers kill fleeing President". Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). news.com.au (2 March 2009). - Elections, Guinea-Bissau (27 May 2009). "On the Radio Waves in Guinea-Bissau". swisspeace. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "Já foi escolhida a data para a realização das eleições presidenciais entecipadas". Bissaudigital.com. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Dabo, Alberto (29 July 2009). "Sanha wins Guinea-Bissau presidential election". Reuters. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- "Tiny Guinea-Bissau becomes latest West African nation hit by coup". Bissau. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- Embalo, Allen Yero (14 April 2012). "Fears grow for members of toppled G.Bissau government". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Guinea-Bissau opposition vows to reach deal with junta | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Tasamba, James (29 November 2019). "Guinea-Bissau's leader concedes election defeat". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Guinea-Bissau: Former PM Embalo wins presidential election". BBC news. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Guinea-Bissau: Many dead after coup attempt, president says". BBC News. 2 February 2022.

Bibliography

- Barry, Boubacar (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Clarence-Smith, W. G. (1975). The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825-1975. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Lobban, Richard Andrew Jr.; Mendy, Peter Karibe (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau (4th ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5310-2.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1989). Histoire des Mandingues de l'Ouest: le royaume du Gabou. Paris, France: Karthala. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Ogilby, John (1670). Africa: being an accurate description of the regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the land of Negroes, Guinee, Aethiopia, and the Abyssines, with all the adjacent islands, either in the Mediterranean, Atlantick, Southern, or Oriental Sea, belonging thereunto: with the several denominations of their coasts, harbors, creeks, rivers, lakes, cities, towns, castles, and villages: their customs, modes, and manners, languages, religions, and inexhaustible treasure: with their governments and policy, variety of trade and barter, and also of their wonderful plants, beasts, birds, and serpents. London: Printed by Tho. Johnson for the author. Retrieved 25 November 2022 – via Early English Books.

- Rodney, Walter Anthony (May 1966). "A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545–1800" (PDF). Eprints. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Wright, Donald R (1987). "The Epic of Kalefa Saane as a guide to the Nature of Precolonial Senegambian Society-and Vice Versa" (PDF). History in Africa. 14: 287–309. doi:10.2307/3171842. JSTOR 3171842. S2CID 162851641 – via JSTOR.