Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld

Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld[Note 1] (14 July 1918 – 12 March 1944) was a Luftwaffe night fighter flying ace of royal descent during World War II. A flying ace or fighter ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat.[1] Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was credited with 51 aerial victories, all of them claimed in nocturnal combat missions.[Note 2]

Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld | |

|---|---|

Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld | |

| Nickname(s) | Egi |

| Born | 14 July 1918 Salzburg, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 12 March 1944 (aged 25) near St. Hubert, German-occupied Belgium |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1936–1944 |

| Rank | Major (major) |

| Unit | ZG 76, NJG 1, NJG 2 |

| Commands held | 5./NJG 2, I./NJG 3, III./NJG 1, NJG 5 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves |

Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was born on 14 July 1918 in Salzburg, Austria and joined the infantry of the Austrian Bundesheer in 1936. He transferred to the emerging Luftwaffe, initially serving as a reconnaissance pilot in the Zerstörergeschwader 76 (ZG 76), before he transferred to the night fighter force. He claimed his first aerial victory on the night of 16 to 17 November 1940. By the end of March, he had accumulated 21 aerial victories for which he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 16 April 1942. He received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves on 2 August 1943, for 45 aerial victories. He was promoted to Major and tasked with leading Nachtjagdgeschwader 5 (NJG 5) in January 1944, before he and his crew were killed in a flight accident on 12 March 1944.

Personal life

Prince Egmont zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was born on 14 July 1918 in Salzburg, Austro-Hungarian Empire as a member of a cadet branch of the ruling House of Lippe. His father was Prince Alfred of Lippe-Weissenfeld (1881-1960) and his mother was born Countess Anna von Goëß (1895-1972). Egmont was the only son of four children. His sisters Carola, Sophie and Theodora were all younger than Egmont.[2] They lived in an old castle in Upper Austria called Alt Wartenburg, which the family inherited through his mother.[3] At birth he had a remote chance of succeeding to the throne of the Principality of Lippe, a small state within the German Empire. However, only months after his birth, Germany became a republic and all the German royal houses were forced to abdicate.

Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld in his younger years was very enthusiastic about the mountains and wildlife. From his fourteenth year he participated in hunting. At the same time he was also very much interested in music and sports and discovered his love for flying at the Gaisberg near Salzburg. Here he attended the glider flying school of the Austrian Aëro Club. He attended a basic flying course with the second air regiment in Graz and Wiener Neustadt even before he joined the military service.[4]

Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld never married or had children. In January 1941 he became acquainted with Hannelore Ide, nicknamed Idelein. She was a secretary for a Luftgau. The two shared a close relationship and spent as much time together as the war permitted, listening to music and sailing on the IJsselmeer until his death in 1944.[5]

Military service

Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld joined the Austrian Bundesheer in 1936 at the age of 18, initially serving in the infantry. In the aftermaths of the 1938 Anschluss, the incorporation of Austria into Greater Germany by Nazi Germany, he transferred to the German Luftwaffe and was promoted to Leutnant in 1939. He had earned his Luftwaffe Pilots Badge on 5 October 1938 and underwent further training at Fürstenfeldbruck, Schleißheim and Vienna-Aspern.[6] His Luftwaffe career started with the II. Gruppe (2nd group) of the Zerstörergeschwader 76 (ZG 76) before he was transferred to the night fighter wing Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (NJG 1) on 4 August 1940.[Note 3] The unit was based at Gütersloh where he familiarised himself with the methods of the night fighters.[7]

Night fighter career

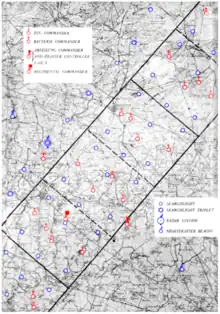

Following the 1939 aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight, Royal Air Force (RAF) attacks shifted to the cover of darkness, initiating the Defence of the Reich campaign.[8] By mid-1940, Generalmajor (Brigadier General) Josef Kammhuber had established a night air defense system dubbed the Kammhuber Line. It consisted of a series of control sectors equipped with radars and searchlights and an associated night fighter. Each sector named a Himmelbett (canopy bed) would direct the night fighter into visual range with target bombers. In 1941, the Luftwaffe started equipping night fighters with airborne radar such as the Lichtenstein radar. This airborne radar did not come into general use until early 1942.[9]

By the summer of 1940, the first night fighters were transferred to Leeuwarden in the Netherlands. Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was one of the pilots included in this small detachment. As early as 20 October 1940, he had taken over command of an independent night fighter commando at Schiphol and later at Bergen. On his first encounter with the Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber, in the night of 16 to 17 November 1940, he claimed a Vickers Wellington bomber from No. 115 Squadron RAF shot down at 02:05 hours.[10] His second victory was claimed on the night of 15 January 1941, when he shot down an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley N1521 of the Linton-on-Ouse based No. 58 Squadron RAF over the northern Netherlands, near the Dutch coast in the Zwanenwater at a nature reserve at Callantsoog.[11] He was wounded in action on 13 March 1941, while flying Bf 110 D-2 (Werknummer 3376 – factory number) of the 4./NJG 1 with his radio operator Josef Renette when he made an emergency landing at Bergen after their aircraft was hit by the defence fire, wounding them both.[12] Shortly after midnight on 10 April 1941, Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld claimed a No. 12 Squadron RAF Wellington over the IJsselmeer, raising NJG 1's victory score to 100. This achievement was celebrated at the Amstel Hotel in Amsterdam with General Kammhuber, Wolfgang Falck, Werner Streib, Helmut Lent and others attending.[13] On 30 June 1941 while flying Bf 110 C-4 (Werknummer 3273) on a practice intercept mission over North Holland, he collided with Bf 110 C-7 (Werknummer 2075) piloted by Leutnant Rudolf Schoenert of the 4./NJG 1 and crashed near Bergen aan Zee.[14] On 19 June 1941 he earned his first of four references in the daily Wehrmachtbericht, a daily bulletin from the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces).[15] By end July 1941, his number of aerial victory claims stood at eleven.[16] Promoted to Oberleutnant he became Staffelkapitän of the 5th Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 (NJG 2—2nd Night Fighter Wing) on 1 November 1941.[17] By the end of 1941, he had claimed a total of 15 aerial victories.[18]

He was awarded the German Cross in Gold (Deutsches Kreuz in Gold) on 25 January 1942 and the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes) on 16 April 1942 after he had shot down 4 RAF bombers in the night of 26 to 27 March 1942, his score standing at 21 aerial victories.[19] Promoted to Hauptmann, Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was made Gruppenkommandeur of the I. Gruppe (1st group) of Nachtjagdgeschwader 3 (NJG 3—3rd Night Fighter Wing) on 15 October 1942,[7] where he claimed two further aerial victories.[20] He was transferred again, taking command of the III. Gruppe (3rd group) of NJG 1 on 11 June 1943.[17] One month later he claimed his 45th aerial victory for which he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub) on 2 August 1943.[19] The presentation was made by Adolf Hitler at the Wolf's Lair, Hitler's headquarters in Rastenburg, present-day Kętrzyn in Poland on 10/11 August. Five other Luftwaffe officers were presented with awards that day by Hitler, Hauptmann Heinrich Ehrler, Oberleutnant Joachim Kirschner, Hauptmann Manfred Meurer, Hauptmann Werner Schröer, Oberleutnant Theodor Weissenberger were also awarded the Oak Leaves, and Major Helmut Lent received the Swords to his Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves.[21]

Wing commander and death

After a one-month hospital stay, Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was promoted to Major and made Geschwaderkommodore of Nachtjagdgeschwader 5 (NJG 5—5th Night Fighter Wing) on 20 February 1944.[22] He and his crew, Oberfeldwebel Josef Renette and Unteroffizier Kurt Röber, were killed in a flying accident on 12 March 1944 on a routine flight from Parchim to Athies-sous-Laon. Above Belgium, they seem to have encountered a bad weather zone with low clouds and a dense snowstorm and it was assumed that the aircraft hit the high Ardennes ground after being forced to fly lower because of ice forming on the wings.[23] The exact circumstances of this flight may never be known, the Bf 110 G-4 C9+CD (Werknummer 720 010—factory number) crashed into the Ardennes mountains near St. Hubert where the completely burned-out wreck was found the following day.[24] The funeral service was held in the city church of Linz on 15 March 1944.[25] Prinz Egmont zur Lippe-Weißenfeld and Prinz Heinrich Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein are buried side by side at Ysselsteyn in the Netherlands.[26]

Summary of career

Aerial victory claims

According to Obermaier, Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld was credited with 51 nocturnal aerial victories.[24] Foreman, Mathews and Parry, authors of Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939 – 1945, list 50 nocturnal victory claims, numerically ranging from 1 to 50. His 49th claim is numerically labeled as his 59th victory.[27] Mathews and Foreman also published Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims, listing Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld with 47 claims, plus four further unconfirmed claims.[28]

| Chronicle of aerial victories[29] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This and the – (dash) indicates unconfirmed aerial victory claims for which Prinz zur Lippe-Weißenfeld did not receive credit.

This and the ? (question mark) indicates information discrepancies listed in Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939 – 1945 and in Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims. | |||||

| Claim | Date | Time | Type | Location | Serial No./Squadron No. |

| – 4. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 – | |||||

| 1 | 17 November 1940 | 02:05 | Wellington[30] | 10 km (6.2 mi) west of Medemblik | |

| 2 | 15 January 1941 | 22:46 | Whitley[31] | 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Petten | Whitley N1521/No. 58 Squadron RAF[32] |

| 3 | 10 April 1941 | 00:59 | Wellington[33] | south of Den Helder | Wellington W5375/No. 12 Squadron RAF[34] |

| 4 | 9 May 1941 | 02:48 | Wellington[35] | Anna Paulowna | Wellington R1226/No. 214 Squadron RAF[36] |

| 5 | 11 May 1941 | 00:20 | Stirling[35] | 10 km (6.2 mi) southwest of Medemblik | Stirling N3654/No. 15 Squadron RAF[37] |

| 6 | 13 June 1941 | 01:10 | Whitley[38] | 2 km (1.2 mi) north of Medemblik | |

| 7 | 19 June 1941 | 00:53 | Wellington[39] | west of Enkhuizen | |

| 8 | 23 June 1941 | 00:15 | Wellington[39] | Insinghuizen | Wellington T2990/No. 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron RAF[40] |

| 9 | 14 July 1941 | 00:28 | Wellington[41] | south Medemblik | Wellington R1502/No. 115 Squadron RAF[42] |

| 10 | 25 July 1941 | 02:23 | Wellington[16] | 3 km (1.9 mi) southwest of Medemblik | |

| 11 | 26 July 1941 | 03:20 | Whitley[16] | 11 km (6.8 mi) west of De Kooy | |

| – 5. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 – | |||||

| 12 | 8 November 1941 | 00:41 | Whitley[43] | east of Medemblik | |

| 13 | 8 November 1941 | 01:20 | Wellington[43] | west of Alkmaar | |

| 14 | 8 November 1941 | 23:03 | Whitley[43] | 18 km (11 mi) north of Alkmaar | |

| 15 | 27 December 1941 | 23:03 | Whitley[18] | 1.5 km (0.93 mi) southwest of Petten | |

| 16 | 24 February 1942 | 21:45 | Hampden[44] | north of Terschelling | Hampden AT194/No. 144 Squadron RAF[45] |

| 17 | 24 February 1942 | 22:02 | Hampden[44] | north of Terschelling | |

| 18 | 26 March 1942 | 22:27 | Wellington[46] | near De Kooy | |

| 19 | 26 March 1942 | 22:40 | Manchester[46] | ||

| 20 | 26 March 1942 | 22:55 | Wellington[46] | north of IJmuiden | |

| 21 | 26 March 1942 | 23:16 | Wellington[46] | near Edam | |

| 22 | 4 June 1942 | 00:50 | Wellington[47] | southeast of Vlieland | |

| 23 | 7 June 1942 | 01:47 | Stirling[48] | west of Terschelling | |

| 24 | 12 June 1942 | 03:08 | Lancaster[49] | north of Ameland | |

| 25 | 21 June 1942 | 01:43 | Halifax[50] | 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Groningen | |

| 26 | 21 June 1942 | 01:45 | Wellington[50] | 20 km (12 mi) northwest of Groningen | |

| 27 | 21 June 1942 | 01:56 | Wellington[50] | north of Ameland | |

| 28 | 26 June 1942 | 01:05 | Wellington[51] | Terschelling | Wellington T2723/No. 20 Operational Training Unit RAF[52][53] |

| 29 | 26 June 1942 | 01:52 | Wellington[51] | 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Vlieland | Hudson AM794/No. 1 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit RAF[54] |

| 30 | 30 June 1942 | 03:08 | Wellington[55] | south of Ameland | |

| 31 | 3 July 1942 | 00:54 | Hampden[55] | south of Koudum | Hampden AT248/No. 420 Squadron RCAF[56] |

| 32 | 3 July 1942 | 01:09 | Wellington[55] | north of Urk | |

| 33 | 3 July 1942 | 03:05 | Stirling[55] | ||

| 34 | 20 July 1942 | 02:52 | Halifax[57] | north of Terschelling | |

| 35?[Note 4] | 28 August 1942 | 01:50 | Wellington[58] | PQ 446, over sea | |

| 36 | 5 September 1942 | 03:39 | Halifax[59] | 5 km (3.1 mi) southwest of Leeuwarden | Halifax W1220/No. 103 Squadron RAF[60] |

| 37 | 23 September 1942 | 23:36 | Wellington[61] | 60 km (37 mi) northwest of Vlieland | |

| – Stab I. Gruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 3 – | |||||

| 38 | 17 January 1943 | 22:13 | Halifax[62] | 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Leer | |

| —?[Note 5] | 21/22 January 1943 | — |

Halifax | north-northwest of Emden | |

| 39 | 14 May 1943 | 01:11 | Halifax[63] | 10 km (6.2 mi) north-northwest of Hengelo | Lancaster ED543/No. 467 Squadron RAAF[64] |

| – Stab III. Gruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 – | |||||

| 40 | 13 June 1943 | 01:22 | Lancaster[65] | 3 km (1.9 mi) northwest of Burgsteinfurt | Halifax JB790/No. 408 (Goose) Squadron RCAF[66] |

| 41 | 13 June 1943 | 01:34 | Lancaster[65] | 6 km (3.7 mi) north of Nienberg | Halifax DK177/No. 76 Squadron RAF[67] |

| 42 | 23 June 1943 | 02:47 | Stirling[68] | 2 km (1.2 mi) south of Markelo | Stirling EF399/No. 75 Squadron RNZAF[69] |

| 43?[Note 4] | 23 June 1943 | 02:55 | Stirling[68] | ||

| 44 | 30 July 1943 | 01:40 | Lancaster[70] | Hägbluer Holz | |

| 45?[Note 4] | 3 August 1943 | 02:26 | Halifax[71] | 20 km (12 mi) south of Stade | |

| 46 | 6 September 1943 | 00:36 | Stirling[72] | 7 km (4.3 mi) southeast of Hassloch | Stirling EH931/No. 620 Squadron RAF[73] |

| 47 | 29 September 1943 | 21:44 | Halifax[74] | 7 km (4.3 mi) south of Hengelo | |

| 48 | 29 September 1943 | 21:55 | Halifax[74] | 2 km (1.2 mi) northwest of Legden | |

| 49 | 16 December 1943 | 18:50 | Lancaster[75] | north of Ahlhorn | Lancaster EE188/No. 9 Squadron RAF[76] |

| 50 | 16 December 1943 | 19:00 | Lancaster[75] | northwest of Nordhorn | Lancaster JB543/No. 7 Squadron RAF[77] |

Awards

- Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe in Gold[78]

- Iron Cross (1939)

- Wound Badge in Black[78]

- German Cross in Gold on 25 January 1942 as Oberleutnant in the 5./Nachtjagdgeschwader 2[80]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

- Knight's Cross on 16 April 1942 as Oberleutnant and Staffelkapitän of the 5./Nachtjagdgeschwader 2[81][82]

- 263rd Oak Leaves on 2 August 1943 as Hauptmann and Gruppenkommandeur of the III./Nachtjagdgeschwader 1[81][83]

Notes

- Regarding personal names: Prinz was a title before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as Prince. Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a legal class, titles preceded the full name when given (Graf Helmuth James von Moltke). Since 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), can be used, but are regarded as a dependent part of the surname, and thus come after any given names (Helmuth James Graf von Moltke). Titles and all dependent parts of surnames are ignored in alphabetical sorting. The feminine form is Prinzessin.

- For a list of Luftwaffe night fighter aces see List of German World War II night fighter aces

- For an explanation of the meaning of Luftwaffe unit designation see Organization of the Luftwaffe during World War II.

- According to Mathews and Foreman, this claim was unconfirmed.[29]

- This unconfirmed claim is not listed by Foreman, Parry and Mathews.[62]

References

Citations

- Spick 1996, pp. 3–4.

- "Egmont, Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld : Genealogics".

- Knott 2008, pp. 129, 199.

- Knott 2008, p. 133.

- Knott 2008, p. 169.

- Knott 2008, pp. 134, 149.

- Knott 2008, p. 168.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 9.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 27.

- Knott 2008, p. 149.

- Knott 2008, pp. 149, 152.

- Knott 2008, p. 163.

- Knott 2008, p. 152.

- Knott 2008, pp. 155, 163.

- Bowman 2016, p. 44.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 26.

- Knott 2008, p. 177.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 33.

- Knott 2008, p. 179.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, pp. 65, 80.

- Hinchliffe 2003, p. 204.

- Aders 1978, p. 229.

- Knott 2008, p. 195.

- Obermaier 1989, p. 57.

- Knott 2008, p. 201.

- Knott 2008, p. 206.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, pp. 12–132.

- Mathews & Foreman 2015, pp. 762–763.

- Mathews & Foreman 2015, p. 763.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 12.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 16.

- Bowman 2016, p. 43.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 18.

- Bowman 2016, p. 32.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 20.

- Wellington R1226.

- Stirling N3654.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 21.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 22.

- Wellington T2990.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 25.

- Wellington R1502.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 32.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 34.

- Hampden AT194.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 36.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 43.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 44.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 45.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 46.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 47.

- Bowman 2012, p. 252.

- Bowman 2016, p. 86.

- Hudson AM794.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 49.

- Hampden AT248.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 50.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 56.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 57.

- Halifax W1220.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 60.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 65.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 80.

- Lancaster ED543.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 85.

- Halifax JB790.

- Halifax DK177.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 89.

- Stirling EF399.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 99.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 100.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 111.

- Stirling EH931.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 118.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 132.

- Lancaster EE188.

- Lancaster JB543.

- Knott 2008, p. 200.

- Thomas 1998, p. 31.

- Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 281.

- Scherzer 2007, p. 510.

- Fellgiebel 2000, p. 293.

- Fellgiebel 2000, p. 70.

Bibliography

- Aders, Gebhard (1978). History of the German Night Fighter Force, 1917–1945. London: Janes. ISBN 978-0-354-01247-8.

- Bowman, Martin (2012). Bomber Command: Reflections of War — Live to Die Another Day June 1942 – Summer 1943. Bransley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-84884-493-3.

- Bowman, Martin (2016). Nachtjagd, Defenders of the Reich 1940–1943. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-4738-4984-6.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer [in German] (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Foreman, John; Parry, Simon; Mathews, Johannes (2004). Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939–1945. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-0-9538061-4-0.

- Hinchliffe, Peter (1998). Luftkrieg bei Nacht 1939–1945 [Air War at Night 1939–1945] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-613-01861-7.

- Hinchliffe, Peter (2003). "The Lent Papers" Helmut Lent. Bristol, UK: Cerberus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84145-105-3.

- Knott, Claire Rose (2008). Princes of Darkness – The lives of Luftwaffe night fighter aces Heinrich Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein and Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-903223-95-6.

- Mathews, Andrew Johannes; Foreman, John (2015). Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims — Volume 2 G–L. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-1-906592-19-6.

- Obermaier, Ernst (1989). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Luftwaffe Jagdflieger 1939–1945 [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Luftwaffe Fighter Force 1939–1945] (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 978-3-87341-065-7.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941–1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941–1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Scutts, Jerry (1998). German Night Fighter Aces of World War 2. Aircraft of the Aces. Vol. 20. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-696-5.

- Spick, Mike (1996). Luftwaffe Fighter Aces. New York: Ivy Books. ISBN 978-0-8041-1696-1.

- Thomas, Franz (1998). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 2: L–Z [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2300-9.

- Accident description for Halifax DK177 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Halifax JB790 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Halifax W1220 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 February 2023.

- Accident description for Hampden AT194 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Hampden AT248 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Hudson AM794 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Stirling EF399 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Stirling EH931 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Stirling N3654 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 February 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ED543 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Lancaster EE188 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Lancaster JB543 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Wellington R1226 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Wellington R1502 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.

- Accident description for Wellington T2990 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 April 2020.