Ernst-Wilhelm Modrow

Ernst-Wilhelm Modrow (5 May 1908 – 10 September 1990) was a German night fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany. He was recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Modrow, along with four other pilots, was the 45th most successful night fighter pilot in the history of aerial warfare.[1] He was credited with 34 nocturnal aerial victories, including one de Havilland Mosquito, claimed in 259 combat missions, 109 of which flown at night.[2] Modrow was the leading proponent of the Heinkel He 219. All but one of his 34 successes were claimed in this aircraft.[3]

Ernst-Wilhelm Modrow | |

|---|---|

| Born | 5 May 1908 Stettin, German Empire |

| Died | 10 September 1990 (aged 82) Kiel, Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1939–45 1950s–64 |

| Rank | Major (Wehrmacht) Oberstleutnant (Bundeswehr) |

| Unit | KGr.z.b.v. 108 LTS (See) 222 NJG 1 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross |

| Other work | Pilot with SCADTA and Luft Hansa |

Early life and career

Modrow was born on 5 May 1908 in Stettin, at the time in the Province of Pomerania in the Kingdom of Prussia. Today, Stettin is Szczecin, the capital city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in Poland. Modrow began his civil flight training in 1929 worked as a pilot for the Colombian-German Air Transport Society (SCADTA—Sociedad Colombo Alemana de Transportes Aéreos) from 1933 to 1937. Modrow then flew the postal routes to South America with the Deutsche Luft Hansa from May 1937 to August 1939.[2][4]

World War II

World War II in Europe began on Friday 1 September 1939 when German forces invaded Poland. Modrow was posted to Kampfgruppe zur besonderen Verwendung 108 (KGr.z.b.v. 108—Fighting Group for Special Use) to fly the Dornier Do 26 flying boat. With this unit he flew maritime aerial reconnaissance and supply missions into Narvik during the Norwegian campaign.[2] On 28 May 1940, his Do 26 D-AGNT "Seeadler" and another Do 26 were moored at Rombaksfjord when they came under attack by Royal Air Force (RAF) Hawker Hurricane fighters from No. 46 Squadron led by the New Zealander Flight Lieutenant Patrick Jameson.[5][6] During the attack, Modrow was severely injured and both aircraft destroyed. In March 1941, following a period of convalescence, he was posted to Blindflugschule 1 (1st Blind Flying School) as an instructor. In April 1942, for one year, Modrow was posted to the Mediterranean Theatre, flying more than 100 transport missions with the Blohm & Voss BV 222 flying boat with the Lufttransportstaffel (See) 222 (LTS (See) 222—222nd Air Transport Squadron Sea). In April 1943, he was transferred to the Luftwaffe Erprobungsstelle See (Maritime Test Site) at Travemünde.[2]

Night fighter

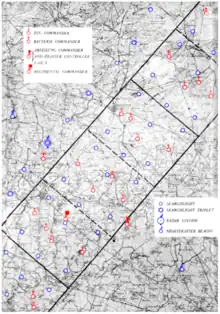

Following the 1939 aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight, RAF attacks shifted to the cover of darkness, initiating the Defence of the Reich campaign.[7] By mid-1940, Generalmajor (Brigadier General) Josef Kammhuber had established a night air defense system dubbed the Kammhuber Line. It consisted of a series of control sectors equipped with radars and searchlights and an associated night fighter. Each sector named a Himmelbett (canopy bed) would direct the night fighter into visual range with target bombers. In 1941, the Luftwaffe started equipping night fighters with airborne radar such as the Lichtenstein radar. This airborne radar did not come into general use until early 1942.[8]

In October 1943, Modrow was trained as night fighter pilot and was posted to I. Gruppe (1st group) of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (NJG 1—Night Fighter Wing 1).[2][Note 1] At the time, the group was under the command of Hauptmann (Captain) Manfred Meurer and was involved in the evaluation of the then new Heinkel He 219 night fighter under combat conditions.[9] On the night of 7/8 March 1944, he claimed his first aerial victory, a de Havilland Mosquito, claimed shot down at 22:30 approximately 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) south of Venlo Airfield.[10] On 30/31 March 1944, Modrow claimed two Handley Page Halifax shot down. The first Halifax was claimed at 04:13 north-northwest of Abbeville, the second at 04:30 south of Abbeville.[11] One of the aircraft shot down by Modrow was Halifax HX322 NP-B from No. 158 Squadron piloted by Flight Sergeant Albert Brice. Of the crew of seven, only Sergeant Kenneth Dobbs, the wireless operator who bailed out, survived the crash near Caumont.[12] The RAF endured its heaviest losses in the strategic bombing campaign of Germany that night. Out of more than 700 planes participating in the Nuremberg raid, 106 were shot down or crash landed on the way home to their base, and more than 700 men were missing, as many as 545 of them dead. More than 160 became prisoners of war.[13][14] In April 1944, although first tests of the He 219 proved the aircraft to be superior to the Messerschmitt Bf 110 in the night fighter role, the Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium) was debating whether to cancel the He 219 production. As part of the assessment team, Modrow rated the He 219 to be faster than the Bf 110. He stated that flying the Bf 110, he would not have shot down the two bombers. In comparison to the Bf 110, the He 219 is much easier to handle in flight, and even in difficult weather conditions, the He 219 proved easier to land.[15]

On 1 April 1944, Modrow was appointed Staffelkapitän (squadron leader) of the 1. Staffel (1st squadron) of NJG 1.[2] On 22/23 April 1944, Modrow was credited with three Avro Lancaster bombers destroyed. He might have misidentified the second and third claim of the night. His second claim might have been Halifax LW633 from No. 425 "Alouette" Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which crashed at 01:55 roughly 30 kilometres (19 miles) southeast of Gilze-Rijen. The other Halifax could have been LV780 from No. 424 "Tiger" Squadron, RCAF. The aircraft crashed at 02:04 about 25 kilometres (16 miles) southeast of Gilze-Rijen.[16] On 27/28 May 1944, three Lancasters shot down were claimed by him, two at 02:25 and 02:35 at 'Brisbar' or 'Bisbar' (probably beacon "Eisbär"[Note 2]) respectively, and a third at 03:28 at Durbuy.[17] He claimed the destruction of a Mosquito at 02:50 on 10/11 June 1944 approximately 8 kilometres (5 miles) south of Alkmaar.[18] The aircraft was Mosquito BX.VI MM125 from No. 571 Squadron piloted by Flight Lieutenant Joe Downey (DFM). The aircraft was returning from Berlin when it came under attack by Modrow. Hit by a short burst of cannon fire, Downey ordered navigator Pilot Officer Ronald Arthur Wellington to bail out. Wellington escaped from the burning aircraft just prior to the midair explosion which killed Downey.[19] Two nights later, he filed claim for the destruction of three Lancaster bombers. The first bomber was claimed at 01:27 at Freiburg, the second at 01:31 about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) west-northwest of Amiens, and the third Lancaster at 01:46 near Krefeld.[20]

On 21/22 June 1944, Modrow claimed four Lancasters shot down, taking his total to 25 aerial victories.[21] That night, RAF Bomber Command had targeted the oil refineries at Wesseling, south of Cologne.[22] No. 44, No. 49 and No. 619 Squadron lost six Lancasters each in this attack.[23] The first two Lancasters were claimed at beacon "Gorilla" at 01:12 and 01:24 respectively.[24][Note 3] The third Lancaster was claimed at 01:39 north-northwest of Duisburg and the fourth at 02:01 north of Deelen.[21][Note 4] On 18/19 August 1944, was credited with a Lancaster shot down, claimed at 02:09 near Zoutkamp.[25] Following this aerial victory, Modrow was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes) on 19 August 1944.[2] The presentation was made by Generalmajor Walter Grabmann, commander of 3. Jagd Division, on 1 September 1944 at Venlo.[26] He claimed his 34th and last aerial victory, a Halifax bomber, on 5/6 January 1945.[27]

Later life

Following World War II, Modrow served in the Bundeswehr until 1964, and retired holding the rank of Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel).[28] He died on 16 September 1990 in Kiel.[29] He was interred at the Parkfriedhof Eichhof in Kiel.[30]

Summary of career

Aerial victory claims

Mathews and Foreman, authors of Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims, researched the German Federal Archives and found records for 34 aerial victory claims. This number includes two de Havilland Mosquito aircraft, five Halifax, 25 Lancaster and two further four-engined bombers of unknown type. All of his aerial victories were claimed in nocturnal combat over the Western Front in defense of the Reich.[31]

Victory claims were logged to a map-reference (PQ = Planquadrat), for example "PQ HF". The Luftwaffe grid map (Jägermeldenetz) covered all of Europe, western Russia and North Africa and was composed of rectangles measuring 15 minutes of latitude by 30 minutes of longitude, an area of about 360 square miles (930 km2). These sectors were then subdivided into 36 smaller units to give a location area 3x4km in size.[32]

| Chronicle of aerial victories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claim | Date | Time | Type | Location | Serial No./Squadron No. | |

| – 2. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 – | ||||||

| 1 | 7 March 1944 | 22:30 | Mosquito | south of Venlo[31] | ||

| 2 | 31 March 1944 | 04:13 | Halifax | vicinity of Abbeville[31] | Halifax LW500/No. 640 Squadron RAF[33] | |

| 3 | 31 March 1944 | 04:30 | Halifax | vicinity of Abbeville[31] | ||

| 4 | 23 April 1944 | 01:10 | Lancaster | Düsseldorf[31] | Lancaster ND353/No. 7 Squadron RAF[34] | |

| 5 | 23 April 1944 | 01:55 | Lancaster | 30 km (19 mi) southeast of Gilze en Rijen[31] | ||

| 6 | 23 April 1944 | 02:04 | Lancaster | 30 km (19 mi) southeast of Gilze en Rijen[31] | ||

| 7 | 25 April 1944 | 00:05 | Lancaster | 18 km (11 mi) northeast of Liège[31] | Lancaster ND328/No. 100 Squadron RAF[35] | |

| 8 | 25 April 1944 | 03:34 | Lancaster | northeast of Liège[31] | ||

| 9 | 2 May 1944 | 00:25 | Halifax | 30–50 km (19–31 mi) northwest of Brussels[31] | Halifax MZ593/No. 51 Squadron RAF[36] | |

| 10 | 12 May 1944 | 00:26 | Lancaster | 15 km (9.3 mi) southeast of Goes[31] | ||

| 11 | 12 May 1944 | 01:04 | Lancaster | PQ HF, over the North Sea[31] | ||

| 12 | 13 May 1944 | 00:02 | Halifax | 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Bergen[31] | Lancaster ND924/No. 635 Squadron RAF[37] | |

| 13 | 13 May 1944 | 01:00 | four-engined bomber | over the North Sea[31] | ||

| 14 | 22 May 1944 | 01:41 | Lancaster | 20 km (12 mi) south-southwest of Finthorn[31] | ||

| 15 | 23 May 1944 | 01:25 | Lancaster | 2.5 km (1.6 mi) south of Assen[31] | Lancaster NE118/No. 626 Squadron RAF[38] | |

| 16 | 28 May 1944 | 02:25 | Lancaster | vicinity of 'Brisbar'[31] | ||

| 17 | 28 May 1944 | 02:35 | Lancaster | vicinity of 'Brisbar'[31] | ||

| 18 | 28 May 1944 | 03:28 | Lancaster | Durbuy[31] | ||

| – 1. Staffel of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 – | ||||||

| 19 | 11 June 1944 | 02:50 | Mosquito | 8 km (5.0 mi) south of Alkmaar[31] | Mosquito MM125/No. 571 Squadron RAF[39] | |

| 20 | 13 June 1944 | 01:27 | Lancaster | Frisburg[31] | Lancaster LM156/No. 15 Squadron RAF[40] | |

| 21 | 13 June 1944 | 01:31 | Lancaster | 10 km (6.2 mi) west-northwest of Amiens[31] | ||

| 22 | 13 June 1944 | 01:46 | Lancaster | vicinity of Krefeld[31] | ||

| 23 | 22 June 1944 | 01:12 | Lancaster | southeast of beacon "Gorilla"[31] | Lancaster ME704/No. 9 Squadron RAF[41] | |

| 24 | 22 June 1944 | 01:24 | Lancaster | beacon "Gorilla"[31] | ||

| 25 | 22 June 1944 | 01:39 | Lancaster | 330° from Duisburg[31] | Lancaster ED532/No. 467 Squadron RAAF[42] | |

| 26 | 22 June 1944 | 02:01 | Lancaster | west of Cologne[31] | ||

| 27 | 21 July 1944 | 01:57 | Lancaster | 40 km (25 mi) southwest of beacon "Biber"[31][Note 5] | ||

| 28 | 19 August 1944 | 03:09 | Lancaster | vicinity of Zoutkamp[31] | Halifax LW538/No. 51 Squadron RAF[43] | |

| 29 | 30 August 1944 | 03:51 | four-engined bomber | PQ LT/05 Ost[31] | Lancaster LM116/No. 103 Squadron RAF[44] | |

| 30 | 23 September 1944 | 22:40 | Lancaster | 45 km (28 mi) west-northwest of Düsseldorf[31] | ||

| 31 | 23 September 1944 | 23:11 | Lancaster | 75 km (47 mi) west-northwest of Düsseldorf[31] | ||

| 32 | 6 November 1944 | 19:24 | Lancaster | PQ GP[31] | ||

| 33 | 6 November 1944 | 19:28 | Lancaster | PQ GP[31] | Lancaster LM742/No. 619 Squadron RAF[45] | |

| 34 | 5/6 January 1945 | — |

Hallifax[31] | |||

Awards

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 19 August 1944 as Hauptmann and Staffelkapitän of the 1./Nachtjagdgeschwader 1[46][29]

- German Cross in Gold on 1 January 1945 Hauptmann in the 1./Nachtjagdgeschwader 1[47]

Notes

- For an explanation of the meaning of Luftwaffe unit designation see Organisation of the Luftwaffe during World War II.

- Beacon "Eisbär"—At Lemmer in 52°52′N 5°35′E

- Beacon "Gorilla"—At Schoonrewoerd in 51°55′N 5°6′E

- According to Hichliffe and Obermaier, Modrow claimed five victories on 21/22 June 1944. This would make him an "ace-in-a-day", a term which designates a fighter pilot who has shot down five or more airplanes in a single day.[2][23]

- Beacon "Biber"—At Oostvoorne in 51°55′N 4°6′E

References

Citations

- Scutts 1998, p. 88.

- Obermaier 1989, p. 170.

- Bowman 2016a, p. 143.

- Boiten 1997, p. 98.

- Goss & Rauchbach 2002, p. 131.

- Hafsten et al. 1991, p. 99.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 9.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 27.

- Remp 2000, p. 84.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 154.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 162.

- Chorley 1997, p. 151.

- Wilson 2008.

- Bowman 2016b.

- Remp 2000, pp. 88–89.

- Bowman 2016a, p. 58.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 180.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 186.

- Bowman 2016a, p. 94.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 187.

- Bowman 2016a, p. 104.

- Zaloga & Groult 2022, pp. 42–43.

- Hinchliffe 1998, p. 280.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 190.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 210.

- Hinchliffe 1998, p. 291.

- Foreman, Parry & Mathews 2004, p. 229.

- Bowman 2016c, p. 245.

- Scherzer 2007, p. 547.

- Brazier 2022, p. 541.

- Mathews & Foreman 2015, p. 863.

- Planquadrat.

- Halifax LW500.

- Lancaster ND353.

- Lancaster ND328.

- Halifax MZ593.

- Lancaster ND924.

- Lancaster NE118.

- Mosquito MM125.

- Lancaster LM156.

- Lancaster ME704.

- Lancaster ED532.

- Halifax LW538.

- Lancaster LM116.

- Lancaster LM742.

- Fellgiebel 2000, p. 256.

- Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 313.

Bibliography

- Brazier, Kevin (2022). The Complete Knight's Cross: The Years of Defeat 1944–1945. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-783-9.

- Bergström, Christer. "Bergström Black Cross/Red Star website". Identifying a Luftwaffe Planquadrat. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Boiten, Theo (1997). Nachtjagd: the night fighter versus bomber war over the Third Reich, 1939–45. London: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-86126-086-4.

- Bowman, Martin (2016a). German Night Fighters Versus Bomber Command 1943–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-4738-4979-2.

- Bowman, Martin (2016b). Nuremberg: The Blackest Night in RAF History: 30/31 March 1944. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-4738-5212-9.

- Bowman, Martin (2016c). Nachtjagd, Defenders of the Reich 1940–1943. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-4986-0.

- Chorley, W. R (1997). Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War: Aircraft and crew losses: 1944. Midland Counties Publications. ISBN 978-0-9045-9791-2.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer [in German] (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Foreman, John; Parry, Simon; Mathews, Johannes (2004). Luftwaffe Night Fighter Claims 1939–1945. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-0-9538061-4-0.

- Goss, Chris; Rauchbach, Bernd (2002). Luftwaffe Seaplanes, 1939–1945: An Illustrated History. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-421-0.

- Hafsten, Bjørn; Larsstuvold, Ulf; Olsen, Bjørn; Stenersen, Sten (1991). Flyalarm — luftkrigen over Norge 1939–1945 [Air Raid Alarm — Air War over Norway 1939–1945] (in Norwegian) (1st ed.). Oslo: Sem og Stenersen AS. ISBN 978-82-7046-058-8.

- Hinchliffe, Peter (1998). Luftkrieg bei Nacht 1939–1945 [Air War at Night 1939–1945] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-613-01861-7.

- Mathews, Andrew Johannes; Foreman, John (2015). Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims — Volume 3 M–R. Walton on Thames: Red Kite. ISBN 978-1-906592-20-2.

- Obermaier, Ernst (1989). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Luftwaffe Jagdflieger 1939 – 1945 [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Luftwaffe Fighter Force 1939 – 1945] (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 978-3-87341-065-7.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Remp, Roland (2000). Der Nachtjäger Heinkel He 219 [The Night Fighter Heinkel He 219] (in German). Oberhaching, Germany: AVIATIC Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-925505-51-5.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Scutts, Jerry (1998). German Night Fighter Aces of World War 2. Aircraft of the Aces. Vol. 20. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-696-5.

- Wilson, Kevin (2008). Men Of Air: The Doomed Youth Of Bomber Command. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-297-85704-4.

- Zaloga, Steven J.; Groult, Edouard A. (2022). The Oil Campaign 1944–45: Draining the Wehrmacht's Lifeblood. New York; Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-4857-4.

- Accident description for Halifax LW500 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Halifax LW538 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Halifax MZ593 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ED532 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 3 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster LM116 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster LM156 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster LM742 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ME704 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ND328 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ND353 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster ND924 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Lancaster NE118 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.

- Accident description for Mosquito MM125 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 March 2023.