Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) was a period of history of the Ottoman Empire beginning with the Young Turk Revolution and ultimately ending with the empire's dissolution and the founding of the modern state of Turkey.

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

The Young Turk Revolution restored the constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics with a two-stage electoral system for the Ottoman parliament. At the same time, a nascent movement called Ottomanism was promoted in an attempt to maintain the unity of the Empire, emphasising a collective Ottoman nationalism regardless of religion or ethnicity. Within the empire, the new constitution was initially seen positively, as an opportunity to modernize state institutions and resolve inter-communal tensions between different ethnic groups.[1]

Additionally, this period was characterised by continuing military failures by the empire. Despite military reforms, the Ottoman Army met with disastrous defeat in the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), resulting in the Ottomans being driven out of North Africa and nearly out of Europe. Continuous unrest leading up to World War I resulted in the 31 March Incident, the 1912 Ottoman coup d'état and the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government became increasingly radicalised during this period, and conducted ethnic cleansing and genocide against the empire's Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek citizens, events collectively referred to as the Late Ottoman genocides. Ottoman participation in World War I ended with defeat and the partition of the empire's remaining territories under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres. The treaty, formulated at the conference of London, allocated nominal land to the Ottoman state and allowed it to retain the designation of "Ottoman Caliphate" (similar to the Vatican, a sacerdotal-monarchical state ruled by the Catholic Pope), leaving it severely weakened. One factor behind this arrangement was Britain's desire to thwart the Khilafat Movement.

The occupation of Constantinople (Istanbul), along with the occupation of Smyrna (Izmir), mobilized the Turkish national movement, which ultimately won the Turkish War of Independence. The formal abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate was performed by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on 1 November 1922. The Sultan was declared persona non grata from the lands the Ottoman Dynasty had ruled since 1299.

Background

Social conflicts

Europe became dominated by nation states with the rise of nationalism in Europe. The 19th century saw the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire which resulted in the establishment of an independent Greece in 1821, Serbia in 1835, and Bulgaria in 1877–1878. Unlike the European nations, the Ottoman Empire made little attempt to integrate conquered peoples through cultural assimilation.[2] Instead, Ottoman policy was to rule through the millet system, consisting of confessional communities for each religion.[lower-alpha 1]

The Empire never fully integrated its conquests economically and therefore never established a binding link with its subjects.[2] Between 1828 and 1908, the Empire tried to catch up with industrialization and a rapidly emerging world market by reforming state and society. The Treaty of Balta Liman (1838) with Great Britain “will abolish all monopolies, allow British merchants and their collaborators to have full access to all Ottoman markets and will be taxed equally to local merchants”. Thus English manufacturers could sell their products cheaply in the Ottoman Empire, and “the Ottomans were unable to ... raise revenues for investments in development projects”,[4] which undermined Ottoman efforts to industrialize. The Ottoman state did try to industrialize. For example, in 1840s, it built a complex of industries west of Istanbul including spinning and weaving mills, a foundry, steam-operated machine works, and a boatyard for small steamships. In the words of Edward Clark:[5] “In variety as well as in number, in planning, in investment, and in attention given to internal sources of raw materials these manufacturing enterprises far surpassed the scope of all previous efforts and mark this period as unique in Ottoman history.” [6]

Inspired by the French Revolution social contract theorists Montesquieu and Rousseau, the Young Ottomans sciety started the movement Ottomanism for accepting all ethnicities and religions in the empire, for equality among millets and equality of subjects before the law. Proponents believed that this could solve social issues.[7] The structure of the Empire was greatly changed by the Tanzimat reforms: the millet system remained in essence, but secular organizations and policies were established; and primary education and conscription were to be applied to non-Muslims and Muslims alike. Michael Hechter argues that the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire was the result of a backlash against Ottoman attempts to institute more direct and central forms of rule over populations which had previously had greater autonomy.[8]

Economic issues

The Capitulations were the main discussion of economic policy during the period. It used to be believed incoming foreign assistance with capitulation could benefit the Empire. Ottoman officials, representing different jurisdictions, sought bribes at every opportunity and withheld the proceeds of a vicious and discriminatory tax system. This ruined every struggling industry by the graft, and fought against every show of independence on the part of Empire's many subject peoples.

The Ottoman public debt was part of a larger scheme of control by the European powers, through which the commercial interests of the world had sought to gain advantages that may not have been of the Empire's interest. The debt was administered by the Ottoman Public Debt Administration and its power was extended to the Imperial Ottoman Bank (or Central bank). The total pre-World War debt of Empire was $716,000,000. France had 60 percent of the total. Germany had 20 percent. The United Kingdom owned 15 percent. The Ottoman Debt Administration controlled many of the important revenues of the Empire. The council had power over financial affairs; its control even extended to determine the tax on livestock in the districts.

Young Turk Revolution

In July 1908, the Young Turk Revolution changed the political structure of the Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) rebelled against the absolute rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II to establish the Second Constitutional Era. On 24 July 1908, Abdul Hamid II capitulated and restored the Ottoman constitution of 1876.

The revolution created multi-party democracy. Once underground, the Young Turk movement declared its parties.[9]: 32 Among them was "Committee of Union and Progress" (CUP), and the "Liberty Party."

There were smaller parties such as Ottoman Socialist Party and ethnic parties which included People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section), Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs, Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party in Palestine (Poale Zion), Al-Fatat (also known as the Young Arab Society; Jam’iyat al-'Arabiya al-Fatat), Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization, and Armenians were organized under the Armenakan, Hunchakian and Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF/Dashnak).

At the onset, there was a desire to remain unified, and the competing groups wished to maintain a common country. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO) collaborated with the members of the CUP, and Greeks and Bulgarians joined under the second biggest party, the Liberty Party. The Bulgarian federalist wing welcomed the revolution, and they later joined mainstream politics as the People's Federative Party. The former centralists of the IMRO formed the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs, and, like the PFP, they participated in 1908 Ottoman general election.

Further disintegration

The de jure Bulgarian Declaration of Independence on 5 October [O.S. 22 September] 1908 from the Empire was proclaimed in the old capital of Tarnovo by Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria, who afterwards took the title "Tsar".

The Bosnian crisis on 6 October 1908 erupted when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, territories formally within the sovereignty of the Empire. This unilateral action was timed to coincide with Bulgaria's declaration of independence (5 October) from the Empire. The Ottoman Empire protested Bulgaria's declaration with more vigour than the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which it had no practical prospects of governing. A boycott of Austro-Hungarian goods and shops occurred, inflicting commercial losses of over 100,000,000 kronen on Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary agreed to pay the Ottomans ₤2.2 million for the public land in Bosnia-Herzegovina.[10] Bulgarian independence could not be reversed.

Just after the revolution in 1908, the Cretan deputies declared union with Greece, taking advantage of the revolution as well as the timing of Zaimis's vacation away from the island.[11] 1908 ended with the issue still unresolved between the Empire and the Cretans. In 1909, after the parliament elected its governing structure (first cabinet), the CUP majority decided that if order was maintained and the rights of Muslims were respected, the issue would be solved with negotiations.

The Second Constitutional Era (1908–1920)

New Parliament

1908 Ottoman general election was preceded by political campaigns. In the summer of 1908, a variety of political proposals were put forward by the CUP. The CUP stated in its election manifesto that it sought to modernize the state by reforming finance and education, promoting public works and agriculture, and the principles of equality and justice.[12] Regarding nationalism, (Armenian, Kurd, Turkic..) the CUP identified the Turks as the "dominant nation" around which the empire should be organized, not unlike the position of Germans in Austria-Hungary. According to Reynolds, only a small minority in the Empire occupied themselves with Pan-Turkism, at least in 1908.[13]

The election was held in October and November 1908. CUP-sponsored candidates were opposed by the Liberals. The latter became a centre for those opposing the CUP. Mehmed Sabahaddin, who returned from his long exile, believed that in non-homogeneous provinces a decentralized government was best. The Liberals were poorly organized in the provinces, and failed to convince minority candidates to contest the election under the Liberty Party banner; it also failed to tap into the continuing support for the old regime in less developed areas.[12]

During September 1908, the important Hejaz Railway opened, construction of which had started in 1900. Ottoman rule was firmly re-established in Hejaz and Yemen with the railroad from Damascus to Medina. Historically, Arabia's interior was mostly controlled by playing one tribal group off against another. As the railroad finished, opposing Wahhabi Islamic fundamentalists reasserted themselves under the political leadership of Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud.

Christian communities of the Balkans felt that the CUP no longer represented their aspirations. They had heard the CUP's arguments before, under the Tanzimat reforms:

Those in the vanguard of reform had appropriated the notion of Ottomanism, but the contradictions implicit in the practical realization of this ideology – in persuading Muslims and non-Muslims alike that the achievement of true equality between them entailed the acceptance by both of obligations as well as rights – posed CUP a problem. October 1908 saw the new regime suffer a significant blow with the loss of Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Crete, over which the empire still exercised nominal sovereignty.[12]

The system became multi-headed, with old and new structures coexisting, until the CUP took full control of the government in 1913 and, under the chaos of change, power was exercised without accountability.

The Senate of the Ottoman Empire was opened by the Sultan on 17 December 1908. The new year brought the results of 1908 elections. Chamber of Deputies gathered on 30 January 1909. The CUP needed a strategy to realize their Ottomanist ideals.[12]

In 1909, public order laws and police were unable to maintain order; protesters were prepared to risk reprisals to express their grievances. In the three months following the inauguration of the new regime there were more than 100 strikes, constituting three-quarters of the labor force of the Empire, mainly in Constantinople and Salonika (Thessaloniki). During previous strikes (Anatolian tax revolts in 1905-1907) the Sultan remained above criticism and bureaucrats and administrators were deemed corrupt; this time CUP took the blame. In the parliament the Liberty Party accused the CUP of authoritarianism. Abdul Hamid's Grand Viziers Said and Kâmil Pasha and his Foreign Minister Tevfik Pasha continued in the office. They were now independent of the Sultan and were taking measures to strengthen the Porte against the encroachments of both the Palace and the CUP. Said and Kâmil were nevertheless men of the old regime.[12]

31 March Incident

After nine months into the new government, discontent found expression in a fundamentalist movement which attempted to dismantle Constitution and revert it with a monarchy. The 31 March Incident began when Abdul Hamid promised to restore the Caliphate, eliminate secular policies, and restore the rule of Islamic law, as the mutinous troops claimed. CUP also eliminated the time for religious observance.[12] Unfortunately for the advocates of representative parliamentary government, mutinous demonstrations by disenfranchised regimental officers broke out on 13 April 1909, which led to the collapse of the government.[9]: 33 On 27 April 1909 the counter-coup was put down using the 11th Salonika Reserve Infantry Division of the Third Army. Some of the leaders of Bulgarian federalist wing like Sandanski and Chernopeev participated in the march on Capital to depose the "attempt to dismantle constitution".[14] Abdul Hamid II was removed from the throne, and Mehmed V became the Sultan. On 5 August 1909, the revised constitution was granted by the new Sultan Mehmed V. This revised constitution, as the one before, proclaimed the equality of all subjects in the matter of taxes, military service (allowing Christians into the military for the first time), and political rights. The new constitution was perceived as a big step for the establishment of a common law for all subjects. The position of Sultan was greatly reduced to a figurehead, while still retaining some constitutional powers, such as the ability to declare war.[15] The new constitution, aimed to bring more sovereignty to the public, could not address certain public services, such as the Ottoman public debt, the Ottoman Bank or Ottoman Public Debt Administration because of their international character. The same held true of most of the companies which were formed to execute public works such as Baghdad Railway, tobacco and cigarette trades of two French companies the "Regie Company", and "Narquileh tobacco".

Italian War, 1911

Italy declared war, the Italo-Turkish War, on the Empire on 29 September 1911, demanding the turnover of Tripoli and Cyrenaica. Italian forces took those areas on 5 November of that year. Although minor, the war was an important precursor of World War I as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states.

The Ottomans lost their last directly ruled African territory. The Italians also sent weapons to Montenegro, encouraged Albanian dissidents, and seized the Dodecanese.[15] Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the disorganized Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the Empire before the war with Italy had ended.

On 18 October 1912, Italy and the Empire signed a treaty in Ouchy near Lausanne. Often called Treaty of Ouchy, but also named as the First Treaty of Lausanne.

1912 election and coup

The Freedom and Accord Party, successor to the Liberty Party, was in power when the First Balkan War broke out in October. The Party of Union and Progress won landslide the 1912 Ottoman general election. Decentralization (the Liberal Union's position) was rejected and all effort was directed toward streamline of the government, streamlining the administration (bureaucracy), and strengthening the armed forces. The CUP, which got the public mandate from the electorate, did not compromise with minority parties like their predecessors (that is being Sultan Abdul Hamid) had been.[15] The first three years of relations between the new regime and the Great Powers were demoralizing and frustrating. The Powers refused to make any concessions over the Capitulations and loosen their grip over the Empire's internal affairs.[16]

When the Italian War and the counterinsurgency operations in Albania and Yemen began to fail, a number of high-ranking military officers, who were unhappy with the counterproductive political involvement in these wars, formed a political committee in the capital. Calling themselves the Savior Officers, its members were committed to reducing the autocratic control wielded by the CUP over military operations. Supported by the Freedom and Accord in parliament, these officers threatened violent action unless their demands were met. Said Pasha resigned as Grand Vizier on 17 July 1912, and the government collapsed. A new government, so called the "Great cabinet", was formed by Ahmet Muhtar Pasha. The members of the government were prestigious statesmen, technocrat government, and they easily received the vote of confidence. The CUP excluded from cabinet posts.[9]: 101

The Ottoman Aviation Squadrons established by largely under French guidance in 1912.[15] Squadrons were established in a short time as Louis Blériot and the Belgian pilot Baron Pierre de Caters performed the first flight demonstration in the Empire on 2 December 1909.

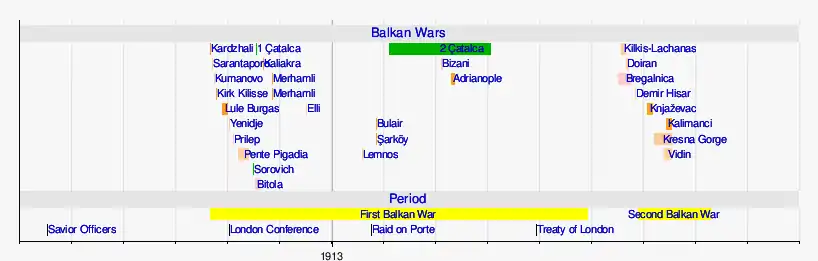

Balkan Wars, 1912–1913

The three new Balkan states formed at the end of the 19th century and Montenegro, sought additional territories from the Albania, Macedonia, and Thrace regions, behind their nationalistic arguments. The incomplete emergence of these nation-states on the fringes of the Empire during the nineteenth century set the stage for the Balkan Wars. On 10 October 1912 the collective note of the powers was handed. CUP responded to demands of European powers on reforms in Macedonia on 14 October.[17]

While the Powers were asking Empire to reform Macedonia, under the encouragement of Russia, a series of agreements were concluded: between Serbia and Bulgaria in March 1912, between Greece and Bulgaria in May 1912, and Montenegro subsequently concluded agreements between Serbia and Bulgaria respectively in October 1912. The Serbian-Bulgarian agreement specifically called for the partition of Macedonia which resulted in the First Balkan War. A nationalist uprising broke out in Albania, and on 8 October, the Balkan League, consisting of Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria, mounted a joint attack on the Empire, starting the First Balkan War. The strong march of the Bulgarian forces in Thrace pushed the Ottoman armies to the gates of Constantinople. The Second Balkan War soon followed. Albania declared independence on 28 November.

_cholera_patients_arriving.png.webp)

The empire agreed to a ceasefire on 2 December, and its territory losses were finalized in 1913 in the treaties of London and Bucharest. Albania became independent, and the Empire lost almost all of its European territory (Kosovo, Sanjak of Novi Pazar, Macedonia and western Thrace) to the four allies. These treaties resulted in the loss of 83 percent of their European territory and almost 70 percent of their European population.[18]

Inter-communal conflicts, 1911–1913

In the two-year period between September 1911 and September 1913 ethnic cleansing sent hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees, or muhacir, streaming into the Empire, adding yet another economic burden and straining the social fabric. During the wars, food shortages and hundreds of thousands of refugees haunted the empire. After the war there was a violent expulsion of the Muslim peasants of eastern Thrace.[18]

Cession of Kuwait and Albania, 1913

The Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913 was a short-lived agreement signed in July 1913 between the Ottoman sultan Mehmed V and the British over several issues. However the status of Kuwait that came to be the only lasting result, as its outcome was formal independence for Kuwait.

Albania had been under Ottoman rule since about 1478. When Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece laid claim to Albanian-populated lands during Balkan Wars, the Albanians declared independence.[19] The European Great Powers endorsed an independent Albania in 1913, after the Second Balkan War leaving outside the Albanian border more than half of the Albanian population and their lands, that were partitioned between Montenegro, Serbia and Greece. They were assisted by Aubrey Herbert, a British MP who passionately advocated their cause in London. As a result, Herbert was offered the crown of Albania, but was dissuaded by the British prime minister, H. H. Asquith, from accepting. Instead the offer went to William of Wied, a German prince who accepted and became sovereign of the new Principality of Albania. Albania's neighbours still cast covetous eyes on this new and largely Islamic state.[18] The young state, however, collapsed within weeks of the outbreak of World War I.[19]

Union and Progress takes control (1913–1918)

At the turn of 1913, the Ottoman Modern Army failed at counterinsurgencies in the periphery of the empire, Libya was lost to Italy, and Balkan war erupted in the fall of 1912. Freedom and Accord flexed its muscles with the forced dissolution of the parliament in 1912. The signs of humiliation of the Balkan wars worked to the advantage of the CUP[20] The cumulative defeats of 1912 enabled the CUP to seize control of the government.

The Freedom and Accord Party presented the peace proposal to the Ottoman government as a collective démarche, which was almost immediately accepted by both the Ottoman cabinet and by an overwhelming majority of the parliament on 22 January 1913.[9]: 101 The 1913 Ottoman coup d'état (23 January), was carried out by a number of CUP members led by Ismail Enver and Mehmed Talaat, in which the group made a surprise raid on the central Ottoman government buildings, the Sublime Porte (Turkish: Bâb-ı Âlî). During the coup, the Minister of the Navy Nazım Pasha was assassinated and the Grand Vizier, Kâmil Pasha, was forced to resign. The CUP established tighter control over the faltering Ottoman state.[9]: 98 The new grand vizier Mahmud Sevket Pasha was assassinated by Freedom and Accord supporters just in 5 months after the coup in June 1913. Cemal Pasha's posting as commendante of Constantinople put the party underground. The execution of former officials had been an exception since the Tanzimat (1840s) period; punishment was usually exile. The public life could not be far more brutish 75 years after the Tanzimat.[20] The Foreign Ministry was always occupied by someone from the inner circle of the CUP except for the interim appointment of Muhtar Bey. Said Halim Pasha who was already Foreign Minister, became Grand Vizier in June 1913 and remained in office until October 1915. He was succeeded in the Ministry by Halil Menteşe.

In May 1913 a German military mission assigned Otto Liman von Sanders to help train and reorganize the Ottoman army. Otto Liman von Sanders was assigned to reorganize the First Army, his model to be replicated to other units; as an advisor [he took the command of this army in November 1914] and began working on its operational area which was the straits. This became a scandal and intolerable for St. Petersburg. The Russian Empire developed a plan for invading and occupying the Black Sea port of Trabzon or the Eastern Anatolian town of Bayezid in retaliation. To solve this issue Germany demoted Otto Liman von Sanders to a rank with which he could barely command an army corps. If there was no solution through Naval occupation of Constantinople, the next Russian idea was to improve the Russian Caucasus Army.

Elections, 1914

The Empire lost territory in the Balkans, where many of its Christian voters were based before the 1914 elections. The CUP made efforts to win support in the Arab provinces by making conciliatory gestures to Arab leaders. Weakened Arab support for Freedom and Accord enabled the CUP to call elections with unionists holding the upper hand. After 1914 elections, the democratic structure had a better representation in the parliament; the parliament that emerged from the elections in 1914 reflected better ethnic composition of the Ottoman population. There were more Arab deputies, which were under-represented in previous parliaments. The CUP had a majority government. Ismail Enver became a Pasha and was assigned as the Minister of War; Ahmet Cemal who was the military governor of Constantinople became Minister of the Navy; and once the postal official Talaat became the Minister of the Interior. These Three Pashas would maintain de facto control of the Empire as a military regime and almost as a personal dictatorship under Talaat Pasha during the World War I. Until the 1919 Ottoman general election, any other input into the political process was restricted with the outbreak of the World War I.[20]

Albanian politics

The Albanians of Tirana and Elbassan, where the Albanian National Awakening spread, were among the first groups to join the constitutional movement, hoping that it would gain their people autonomy within the empire. However, due to shifting national borders in the Balkans, the Albanians had been marginalized as a nation-less people. The most significant factor uniting the Albanians, their spoken language, lacked a standard literary form and even a standard alphabet. Under the new regime the Ottoman ban on Albanian-language schools and on writing the Albanian language lifted. The new regime also appealed for Islamic solidarity to break the Albanians' unity and used the Muslim clergy to try to impose the Arabic alphabet. The Albanians refused to submit to the campaign to "Ottomanize" them by force. As a consequence, Albanian intellectuals meeting, the Congress of Manastir on 22 November 1908, chose the Latin alphabet as a standard script.

Arab politics

The Hauran Druze Rebellion was a violent Druze uprising in the Syrian province, which erupted in 1909. The rebellion was led by the al-Atrash family, in an aim to gain independence. A business dispute between Druze chief Yahia bey Atrash in the village of Basr al-Harir escalated into a clash of arms between the Druze and Ottoman-backed local villagers.[21] Though it is the financial change during second constitutional area; the spread of taxation, elections and conscription, to areas already undergoing economic change caused by the construction of new railroads, provoked large revolts, particularly among the Druzes and the Hauran.[22] Sami Pasha al-Farouqi arrived in Damascus in August 1910, leading an Ottoman expeditionary force of some 35 battalions.[21] The resistance collapsed.[21]

In 1911, Muslim intellectuals and politicians formed "The Young Arab Society", a small Arab nationalist club, in Paris. Its stated aim was "raising the level of the Arab nation to the level of modern nations." In the first few years of its existence, al-Fatat called for greater autonomy within a unified Ottoman state rather than Arab independence from the empire. Al-Fatat hosted the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris, the purpose of which was to discuss desired reforms with other dissenting individuals from the Arab world. They also requested that Arab conscripts to the Ottoman army not be required to serve in non-Arab regions except in time of war. However, as the Ottoman authorities cracked down on the organization's activities and members, al-Fatat went underground and demanded the complete independence and unity of the Arab provinces.[23]

Nationalist movement become prominent during this Ottoman period, but it has to be mentioned that this was among Arab nobles and common Arabs considered themselves loyal subjects of the Caliph.[24]: 229 Instead of Ottoman Caliph, the British, for their part, incited the Sharif of Mecca to launch the Arab Revolt during the First World War.[24]: 8–9

Armenian politics

In 1908, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) or Dashnak Party embraced a public position endorsing participation and reconciliation in the Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire and the abandonment of the idea of an independent Armenia. Stepan Zorian and Simon Zavarian managed the political campaign for the 1908 Ottoman Elections. ARF field workers were dispatched to the provinces containing significant Armenian populations; for example, Drastamat Kanayan (Dro), went to Diyarbakir as a political organizer. The Committee of Union and Progress could only able to bring 10 Armenian representatives to the 288 seats in the 1908 election. The other 4 Armenians represented parties with no ethnic affiliation. The ARF was aware that the elections were shaky ground and maintained its political direction and self-defence mechanism intact and continued to smuggle arms and ammunition.[9]: 33

On 13 April 1909, while Constantinople was dealing with the consequences of 31 March Incident, an outbreak of violence, known today as the Adana Massacre, shook in April the ARF-CUP relations to the core. On 24 April the 31 March Incident and suppression of the Adana violence followed each other. The Ottoman authorities in Adana brought in military forces and ruthlessly stamped out both real opponents, while at the same time massacring thousands of innocent people. In July 1909, the CUP government announced the trials of various local government and military officials, for "being implicated in the Armenian massacres.".

On 15 January 1912, the Ottoman parliament dissolved and political campaigns began almost immediately. After the election, on 5 May 1912, Dashnak officially severed the relations with the Ottoman government; a public declaration of the Western Bureau printed in the official announcement was directed to "Ottoman Citizens." The June issue of Droshak ran an editorial about it.[25]: 35

In October 1912, George V of Armenia engaged in negotiations with General Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov to discuss Armenian reforms inside the Russian Empire. In December 1912, Kevork V formed the Armenian National Delegation and appointed Boghos Nubar. The delegation established itself in Paris. Another member appointed to the delegation was James Malcolm who resided in London and became the delegation's point man in its dealings with the British. In early 1913, Armenian diplomacy shaped as Boghos Nubar was to be responsible for external negotiations with the European governments, while the Political Council "seconded by the Constantinople and Tblisi Commissions" were to negotiate the reform question internally with the Ottoman and Russian governments.[9]: 99 The Armenian reform package was established in February 1914 based on the arrangements nominally made in the Treaty of Berlin (1878) and the Treaty of San Stefano. The plan called for the unification of the Six Vilayets and the nomination of a Christian governor and religiously balanced council over the unified provinces, the establishment of a second Gendarmerie over Ottoman Gendarmerie commanded by European officers, the legalization of the Armenian language and schools, and the establishment of a special commission to examine land confiscations empowered to expel Muslim refugees. The most important clause was obligating the European powers to enforce the reforms, by overriding the regional governments.[lower-alpha 2][9]: 104–105

During the spring of 1913, the provinces faced increasingly worse relations between Kurds and Armenians that created an urgent need for the ARF to revive its self-defence capability. In 1913, the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (followed by other Ottoman political parties) changed its policy and stopped cooperating with the CUP, moving out of the concept of Ottomanism and developing its own kind of nationalism.[26]

From the end of July to 2 August 1914, the Armenian congress at Erzurum happened. There was a meeting between the Committee of Progress and Union and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Armenian liaisons Arshak Vramian, Zorian and Khatchatour Maloumian and Ottoman liaisons Dr. Behaeddin Shakir, Omer Naji, and Hilmi Bey were accompanied by an international entourage of peoples from the Caucasus. The CUP requested to incite a rebellion of Russian Armenians against the Tsarist regime in Russian Armenia, in order to facilitate the conquest of Transcaucasia in the event of the opening up of the Caucasus Campaign.[27] Around the same time, a representative meeting of Russian Armenians assembled in Tiflis, Russian Armenia. The Tsar asked Armenian's loyalty and support for Russia in the conflict.[28] The proposal was agreed upon and nearly 20,000 Armenians who responded to the call of forming Armenian volunteer units inside the Russian Caucasus Army, of which only 7,000 were given arms.[29] On 2 November, the first engagement of the Caucasus Campaign began (the Bergmann Offensive), and on 16 December 1914, the Ottoman Empire officially dismantled the Armenian reform package.

Ottoman intelligence services detected a plot by Hunchakian operatives to assassinate leading CUP members, and but foiled the plot in a single operation in July 1914.[9]: 108 The trials took a year and the participants, named the 20 Hunchakian gallows were executed on 15 June 1915.

Kurdish politics

The first Kurds to challenge the authority of the Ottoman Empire did so primarily as Ottoman subjects, rather than national Kurds. Abdul Hamid responded with a policy of repression, but also of integration, co-opting prominent Kurdish opponents into the Ottoman power structure with prestigious positions in his government. This strategy appeared successful given the loyalty displayed by the Kurdish Hamidiye Cavalry.[30]

In 1908, after the overthrow of Sultan, the Hamidiye was disbanded as an organized force, but as they were "tribal forces" before official recognition by the Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1892, they stayed as "tribal forces" after dismemberment. The Hamidiye Cavalry is often described as a failure because of its contribution to tribal feuds.[31]

Shaykh Abd al Qadir in 1910 appealed to the CUP for an autonomous Kurdish state in the east. That same year, Said Nursi travelled through the Diyarbakir region and urged Kurds to unite and forget their differences, while still carefully claiming loyalty to the CUP.[32] Other Kurdish Shaykhs in the region began leaning towards regional autonomy. During this time, the Badr Khans had been in contact with discontented Shaykhs and chieftains in the far east of Anatolia ranging to the Iranian border, more in the framework of secession, however. Shaykh Abd al Razzaq Badr Khan eventually formed an alliance with Shaykh Taha and Shaykh Abd al Salam Barzani, another powerful family.

In 1914, because of the possible Kurdish threat as well as the alliance's dealings with Russia, Ottoman troops moved against this alliance. Two brief and minor rebellions, the rebellions of Barzan and Bitlis, were quickly suppressed.[33]

In 1914, General Muhammad Sharif Pasha offered his services to the British in Mesopotamia. Elsewhere, members of the Badr Khan family held close relations with Russian officials and discussed their intentions to form an independent Kurdistan.[34]

Yemenese politics

Yemen Vilayet was a first-level administrative division of the Empire. In the late 19th century, the Zaidis rebelled against the Empire, and Imam Mohammed ibn Yahya laid the foundation of a hereditary dynasty.[35] When he died in 1904, his successor Imam Yahya ibn Mohammed led the revolt against the Empire in 1904–1905, and forced them to grant important concessions to the Zaidis.[35] The Ottoman agreed to withdraw the civil code and restore sharia in Yemen.[35] In 1906, the Idrisi leaders of Asir rebelled against the Ottomans. By 1910 they controlled most of Asir, but they were ultimately defeated by Ottoman Army and Hejazi forces.[36] Ahmed Izzet Pasha concluded a treaty with Imam Yahya in October 1911, by which he was recognized as temporal and spiritual head of the Zaidis, was given the right to appoint officials over them, and collect taxes from them. The Ottomans maintained their system of government in the Sunni-majority parts of Yemen.[35]

In March 1914, the Anglo-Turkish Treaty delimited the border between Yemen and the Aden Protectorate.[35] This was the backdrop to the later division in two Yemeni states (up to 1990).

Zionist politics

The World Zionist Organization was established in Constantinople; Theodor Herzl had tried to set up debt relief for Sultan Abdul Hamid II in exchange for Palestinian lands. Until the First World War its activities focused on cultural matters, although political aims were never absent.[37] Before the First World War, Herzl's attempts to reach a political agreement with the Ottoman rulers of Palestine were unsuccessful. But on 11 April 1909, Tel Aviv was founded on the outskirts of the ancient port city of Jaffa. The World Zionist Organization supported small-scale settlement in Palestine and focused on strengthening Jewish feeling and consciousness and on building a worldwide federation. At the start of World War I most Jews (and Zionists) supported the German Empire in its war against the Russian Empire. The Balfour Declaration (dated 2 November 1917) and Henry McMahon had exchanged letters with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca in 1915, a shift to another concept (Jewish national home vs. Jewish state) which is explained under Homeland for the Jewish people.

Foreign policy

The interstate system at the beginning of the twentieth century was a multipolar one, with no single or two states pre-eminent. Multipolarity traditionally had afforded the Ottomans the ability to play-off one power against the other.[38] Initially, the CUP and Freedom and Accord turned to Britain. Germany had supported the Hamidian regime and acquired a strong foothold. By encouraging Britain to compete against Germany and France, the Ottomans hoped to break France and Germany's hold and acquire greater autonomy for the Porte. Hostility to Germany increased when her ally Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. The pro-Unionist Tanin went so far as to suggest that Vienna's motive in carrying out this act was to strike a blow against the constitutional regime and assist reaction in order to bring about its fall.[39] Two prominent Unionists, Ahmed Riza Pasha and Dr. Nazim Pasha, were sent to London to discuss options of cooperation with Sir Edward Grey and Sir Charles Hardinge.

Our habit was to keep our hands free, though we made ententes and friendships. It was true that we had an alliance with Japan, but it was limited to certain distant questions in the Far East.[lower-alpha 3]

They [Ottoman delegate] replied that Empire was the Japan of the Near East (prompting to Meiji Restoration period which spanned from 1868 to 1912), and that we already had the Cyprus Convention which was still in force.

I said that they had our entire sympathy in the good work they were doing in the Empire; we wished them well, and we would help them in their internal affairs by lending them men to organize customs, police, and so forth, if they wished them.[39]

Foreign Minister Tevfik's successor, Mehmed Rifat Pasha was a career diplomat from a merchant family. The CUP, who were predominantly civilian, resented the intrusion of the army into government.[16] The CUP, who seized power from Freedom and Accord in January 1913, were more convinced than ever that only an alliance with Britain and the Entente could guarantee the survival of what remained of the Empire. In June, therefore, the subject of an Anglo-Turkish alliance was reopened by Tevfik Pasha, who simply restated his proposal of October 1911. Once again the offer was turned down.

Sir Louis Mallet, who became Britain's Ambassador to the Porte in 1914, noted that

Turkey’s way of assuring her independence is by an alliance with us or by an undertaking with the Triple Entente. A less risky method [he thought] would be by a treaty or Declaration binding all the Powers to respect the independence and integrity of the present Turkish dominion, which might go as far as neutralization, and participation by all the Great Powers in financial control and the application of reform.

The CUP felt betrayed by what they considered was Europe's bias during the Balkan Wars, and therefore they had no faith in Great Power declarations regarding the Empire's independence and integrity; the termination of European financial control and administrative supervision was one of the principal aims of CUP's policies. Though these imperial powers had experienced relatively few major conflicts between them over the previous hundred years, an underlying rivalry, otherwise known as "the Great Game", had exacerbated the situation to such an extent that resolution was sought. Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 brought shaky British-Russian relations to the forefront by solidifying boundaries that identified their respective control in Persia, Afghanistan. Overall, the Convention represented a carefully calculated move on each power's part in which they chose to value a powerful alliance over potential sole control over various parts of Central Asia. The Ottoman Empire lied on the crossroads to Central Asia. The Convention served as the catalyst for creating a "Triple Entente", which was the basis of the alliance of countries opposing the Central Powers. Ottoman Empire's path in Ottoman entry into World War I was set with that agreement, which ended the Great Game.

One way to challenge and undermine the army's position was by attacking Germany in the press and supporting friendship with Germany's rival, Great Britain. But neither Britain nor France responded to CUP's advance of friendship. In fact France resented the government's (Porte) desire to acquire financial autonomy.[16]

In early 1914 the Constantinople was concerned with three main goals. The first was improving relations with Bulgaria; the second was to encourage support from the Germans, and the third was to settle negotiations with Europe about the Armenian reform.

With regard to the first, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria showed sympathy to one another because they suffered as a result of the territories lost with the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). They also had bitter relations with Greece. They would eventually sign a secret treaty of alliance, and during World War I, fight on the same side.

With regard to the second, there were three military missions active at the turn of 1914. These were the British Naval Mission led by Admiral Limpus, the French Gendarme Mission led by General Moujen, and the German Military Mission led by Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz. The German Military Mission become the most important among these three. The history of German-Ottoman military relations went back to the 1880s. The Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha (12 June 1913 – 4 February 1917) and Ottoman Minister of War Ahmet Izzet Pasha (11 June 1913 – 3 January 1914) were instrumental in developing the initial relations. Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered General Goltz to establish the first German mission. General Goltz served two periods within two years. In early 1914, the Ottoman Minister of War became the former military attaché to Berlin, Enver Pasha. About the same time, General Otto Liman von Sanders was nominated to the command of the German 1st Army.

With regard to the third, an Armenian reform package was negotiated with the Russian Empire. Russia, acting on behalf of the Great Powers, played a crucial role introducing reforms for the Armenian citizens of the Empire. The Armenian reform package, which was solidified in February 1914 and was based on the arrangements nominally made in the Treaty of Berlin (1878) and the Treaty of San Stefano. According to this arrangement the inspectors general, whose powers and duties constituted the key to the question, were to be named for a period of ten years, and their engagement was not to be revocable during that period.[lower-alpha 4]

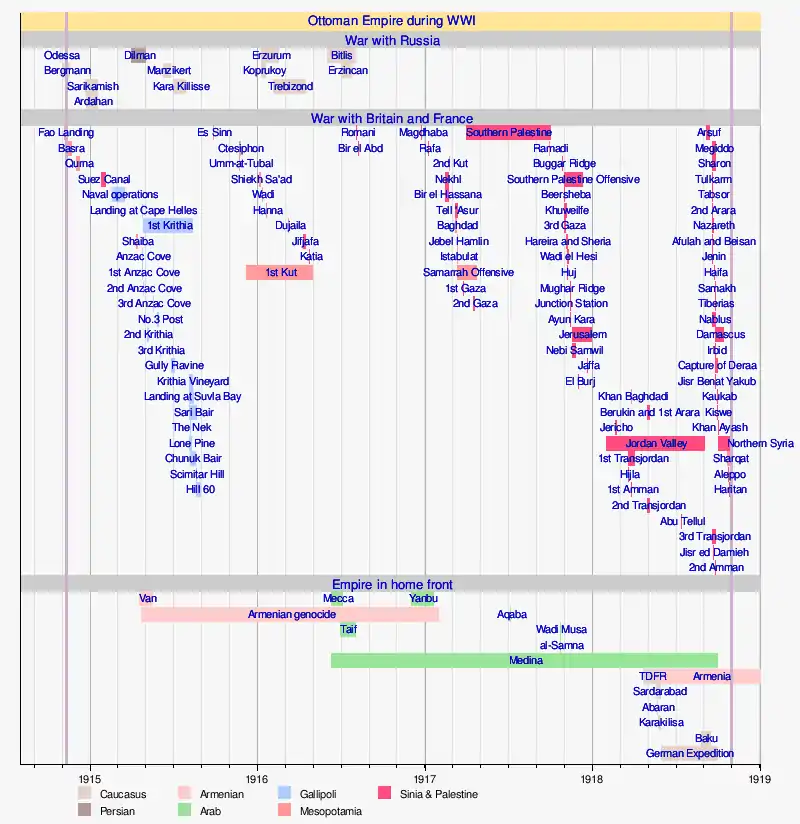

World War I

The Ottoman Empire entered WWI with the attack on Russia's Black Sea coast on 29 October 1914. The attack prompted Russia and its allies, Britain and France, to declare war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914. The Ottoman Empire was active in the Balkans theatre and Middle Eastern theatre – the latter had five main campaigns: the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, the Mesopotamian Campaign, the Caucasus Campaign, the Persian Campaign, and the Gallipoli Campaign. There were also several minor campaigns: the North African Campaign, the Arab Campaign and the South Arabia Campaign. There were several important Ottoman victories in the early years of the war, such as the Battle of Gallipoli and the Siege of Kut. The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 31 October 1918, ending the Ottoman participation in World War I.

|

Genocide of minorities

Mehmet VI (1918–1922)

Just before the end of World War I, Sultan Mehmet V died and Mehmed VI became the new Sultan.

The Occupation of Constantinople took place in accordance with the Armistice of Mudros, ending the Ottoman participation in World War I. The occupation had two stages: the initial occupation took place from 13 November 1918 to 16 March 1920; from 16 March 1920 – Treaty of Sèvres. The year 1918 saw the first time Constantinople had changed hands since the Ottoman Turks conquered the Byzantine capital in 1453. An Allied military administration was set up early in December 1918. Hagia Sophia was converted back into a cathedral by the Allied administration, and the building was returned temporarily to the Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch.

The CUP members were court-martialled during the Turkish courts-martial of 1919–1920 with charges of subversion of the constitution, wartime profiteering, and the massacres of both Greeks and Armenians.[41] The courts-martial became a stage for political battles. The trials helped Freedom and Accord root out the CUP from the political arena. The fall of the CUP allowed the Palace to regain the initiative once again, though only for less than a year. The British also rounded up a number of members of the Imperial Government and interned them in Malta, only for them to be exchanged in the future for British POWs without further trial.[42] Sir Gough-Calthorpe included only members of the Government of Tevfik Pasha and the military/political personalities.

Discredited members of the Ottoman regime were resurrected in order to form ephemeral governments and conduct personal diplomacy. Thus, Ahmet Tevfik Pasha formed two ministries between November 1918 and March 1919, to be followed by Abdul Hamid's brother-in-law Damat Ferid Pasha who led three cabinets in seven months. Damad Ferid, having served in diplomatic missions throughout Europe during the Hamidian era, and having been acquainted with European statesmen during his tenure as a Liberal politician, was considered an asset in the negotiations for the very survival of the Ottoman state and dynasty.

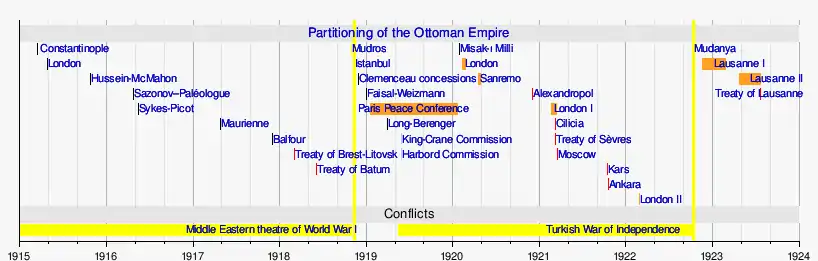

Partitioning

After the war, the doctrine of Ottomanism lost its credibility. As parts of the Empire were integrated into the world economy, certain regions (the Balkans, Egypt, Iraq, and Hijaz) established closer economic links with Paris and London, or even with British India, than with Constantinople, which became known in English as Istanbul around 1930.

The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire began with the Treaty of London (1915) and continued with mostly bilateral multiple agreements among the Allies. The initial peace agreement with the Ottoman Empire was the Armistice of Mudros. This was followed by the Occupation of Constantinople. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire brought international conflicts which were discussed during the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. The peace agreement, the Treaty of Sèvres, was eventually signed by the Ottoman Empire (not ratified) and the Allied administration. The result of the Peace Settlement was that every indigenous group of the Empire would acquire its own state.

Treaty of Sèvres

The text of the Treaty of Sèvres was not made public to the Ottoman public until May 1920. The Allies decided that the Empire would be left only a small area in Northern and Central Anatolia to rule. Contrary to general expectations, the Sultanate along with the Caliphate was not terminated, and it was allowed to retain capitol and a small strip of territory around the city, but not the straits. The shores of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles were planned to be internationalised, so that the gates of the Black Sea would be kept open. West Anatolia was to be offered to Greece, and East Anatolia was to be offered to Armenia. The Mediterranean coast, although still a part of the Empire, was partitioned between two zones of influence for France and Italy. The interior of Anatolia, the first seat of Ottoman power six centuries ago, would retain Ottoman sovereignty.

The idea of an independent Armenian state survived the demise of Ottoman Empire through the Democratic Republic of Armenia, later conquered by the Bolsheviks.[lower-alpha 5]

In 1918, Kurdish tribal leader Sharif Pasha pressed the British to adopt a policy supporting autonomous Kurdish state. He suggested that British officials be charged with administering the region. During the Paris Peace Conference, a Kurdo-Armenian peace accord was reached between Sharif Pasha and Armenian representatives at the conference in 1919. The British thought that this agreement would increase the likelihood of independent Kurdish and Armenian states and therefore create a buffer between British Mesopotamia and the Turks.[33]

The Arab forces were promised a state that included much of the Arabian Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent; however, the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France provided for the territorial division of much of that region between the two imperial powers.

The Allies dictated the terms of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire with the Treaty of Sèvres. The Turkish nationalist Ottoman Parliament rejected these terms, as they did not conform to the Parliament's own conditions for partition, the Misak-ı Millî (English: National Pact) published in early 1920. No Ottoman assent was possible while Parliament remained intransigent.

Following the Conference of London on 4 March 1920, the Allies decided to actively suppress Turkish nationalist opposition to the Treaty. On 14 March 1920, Allied troops moved to occupy key buildings and arrest nationalists in Constantinople. Parliament met a final time on 18 March 1920 before being dissolved by Sultan Mehmed VI on 11 April 1920. Many parliamentarians relocated to Ankara and formed a new government.

The Allies were freed to deal with the Sultan directly. Mehmed VI signed the Treaty on 10 August 1920. The Imperial Government in Constantinople attempted and failed to convene the Senate to ratify the treaty; its legitimacy was fatally undermined by the Turkish nationalists' refusal to cooperate. The resulting Turkish War of Independence and the subsequent nationalist victory permanently prevented the Treaty from being ratified.

The Turkish War of Independence ended with the Turkish nationalists in control of much of Anatolia. On 1 November 1922 the Turkish provisional government formally declared the Ottoman Sultanate and, with it, the Ottoman Empire to be abolished. Mehmed VI departed Constantinople and into exile on 17 November 1922. The Allies and Turks met in Lausanne, Switzerland to discuss a replacement for the unratified Treaty of Sèvres.

End of the Ottoman Empire

The resulting Treaty of Lausanne secured international recognition for the new Turkish state and its borders. The Treaty was signed on 24 July 1923 and ratified in Turkey on 23 August 1923. The Republic of Turkey was formally declared on 29 October 1923.

The following year on 23 April 1924, the republic declared 150 personae non gratae of Turkey, including the former Sultan, to be personae non-gratae. Most of these restrictions were lifted on 28 June 1938.

Image gallery

Abdülhamid II

Abdülhamid II Mehmed V

Mehmed V Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI

See also

Footnotes

- From the 15th century ordinary functions of government were left out of the Empire's control and each millet began to run their own schools, to collect taxes to support welfare for its own group, to organize and police its own neighborhoods and to punish transgressors according to its own laws in its own courts. Under this system, different religious and ethnic groups enjoyed a wide range of religious and cultural freedoms and considerable administrative, fiscal and legal autonomy.[3]

- List of religions under the inspectorates were Muslim, Orthodox Christian, Apostolic Christian, Catholic Christian, Evangelical Christian, Syriac Orthodox Christian, and Jews. Kurds who were fighting for autonomy in the same region of the inspectorates were classified as Muslim. In 1908, the Ottoman parliament had 288 seats and 14 were occupied by Armenians.

- Regarding the alliance's provisions for mutual defense, it was aimed for Japan to enter the First World War on the British side.

- The Russian cable informing the coming agreement: "Thus the Act of January 22nd 1914 signifies without doubt the opening of a new and happier era in the history of the Armenian people. In political significance: it is comparable with the Firman of 1870 in which the Bulgarian Exarchate was founded and the Bulgars were freed from Greek guardianship. The Armenians must feel that the first step has been taken towards releasing them from the Turkish yoke. The agreement of January 26th 1914 has at the same time great significance for the international status of Russia. It has been signed personally by the Grand Vizier and Russia's representative and pledges the Turks to hand to the Powers a note the contents of which have been precisely set forth. The outstanding role of Russia in the Armenian question is thus officially emphasized and Art 16 of the Treaty of San Stefano to some extent ratified."[40]

M Gulkievitch the Charge d'Affaires of the Russian Embassy - About First Republic of Armenia.

"In the summer of 1918, the Armenian national councils reluctantly transferred from Tiflis to Yerevan to take over the leadership of the republic from the popular dictator Aram Manukian and the renowned military commander Drastamat Kanayan. It then began the daunting process of establishing a national administrative machinery in an isolated and landlocked misery. This was not the autonomy or independence which Armenian intellectuals had dreamed of and for which a generation of youth had been sacrificed. Yet, as it happened, it was here that the Armenian people were destined to continue [their] national existence."[43]

First Republic of Armenia 28 May 1919 – 2 December 1920.— R.G. Hovannisian

References

- Reynolds 2011, p. 1

- Kent 1996, p. 18

- Quataert, D. (2005). The Ottoman Empire 1700–1922. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 178.

- Shahid Alam: Bernard Lewis - Scholarship or Sophistry? Studies in Contemporary Islam 4, 1 (Spring 2002): 53-80, p 15

- M. Shahid Alam op. cit. p 15

- Edward Clark, “The Ottoman Industrial Revolution,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 5, 1 (1974): 67

- Maksudyan, Nazan (2014). Orphans and Destitute Children in the Late Ottoman Empire. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 103.

- Hechter, Michael (2001). Containing nationalism. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–77. ISBN 0-19-924751-X. OCLC 470549985. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Erickson, Edward (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137362209.

- Albertini 2005, p. 277.

- Ion, Theodore P. (April 1910). "The Cretan Question". The American Journal of International Law. 4 (2): 276–284. doi:10.2307/2186614. JSTOR 2186614. S2CID 147554500.

- Finkel 2007, pp. 512–16

- Reynolds 2011, p. 23

- van Millingen, Alexander (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–9.***Please note a wikisource link is not available to the EB1922 article [Ottoman Empire]***

- Nicolle 2008, p. 161

- Kent 1996, p. 13

- Archives Diplomatiques. third series. Vol. 126. p. 127.

- Nicolle 2008, p. 162

- Zickel, Raymond; Iwaskiw, Walter R. (1994). ""National Awakening and the Birth of Albania, 1876–1918", Albania: A Country Study". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- (Finkel 2007, pp. 526–27)

- Rogan, E.L. (2002). Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921. Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780521892230. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2013 – via Google Books.

- Schsenwald, William L. (Winter 1968). "The Vilayet of Syria, 1901–1914: A re-examination of diplomatic documents as sources". Middle East Journal. 22 (1): 73.

- Choueiri, pp.166–168.

- Karsh, Islamic Imperialism

- Erickson, Edward (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137362209.

- Dasnabedian, Hratch, "The ideological creed" and "The evolution of objectives" in "a balance sheet of the ninety years", Beirut, 1985, pp. 73–103

- Hovannisian, Richard G. The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. p. 244.

- "[no article cited]". The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 28. 1920. p. 412.

- Pasdermadjian, G. (Armen Garo) (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War. Boston, MA: Hairenik Pub. Co. p. 20.

- (Laçiner & Bal 2004, pp. 473–504)

- (McDowall 1996, p. 61)

- McDowall 1996, p. 98

- McDowall 1996, pp. 131–137

- Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 081563093X.

- (Chatterji 1973, pp. 195–197)

- (Minahan 2002, p. 195)

- Finkel 2007, p. 529

- Reynolds 2011, p. 26

- Kent 1996, p. 12

- Paşa, Cemal (1922). Memories of a Turkish Statesman-1913-1919. George H. Doran Company. p. 274.

- Armenien und der Völkermord: Die Istanbuler Prozesse und die Türkische Nationalbewegung. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition. 1996. p. 185.

- "Turkey's EU minister, Judge Giovanni Bonello and the Armenian genocide – 'Claim about Malta Trials is nonsense'". The Malta Independent. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (eds.). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. p. 98.

Bibliography

- Akın, Yiğit (2018). When the War Came Home: The Ottomans' Great War and the Devastation of an Empire. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-503-60490-2.

- Albertini, Luigi (2005). The Origins of the War of 1914. Vol. I. New York: Enigma Books.

- Bandžović, S. (2003). "Ratovi i demografska deosmanizacija Balkana (1912-1941)" [Wars and Demographic De-Ottomanization of the Balkans (1912–1941)]. Prilozi. Sarajevo. 32: 179–229.

- David, Murphy (2008). The Arab Revolt 1916–18 Lawrence sets Arabia Ablaze (3 ed.). London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-339-1.

- Erickson, Edward (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137362209.

- Erickson, Edward (2001). Order to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-313-31516-7.

- Erickson, Edward (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Westport: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Finkel, Caroline (2007) [2005]. Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00850-6.

- McDowall, David (1996). A Modern History of the Kurds. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1850436533.

- Nicolle, David (2008). The Ottomans: Empire of Faith. Thalamus Publishing. ISBN 978-1902886114.

- Fromkin, David (2009). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. Macmillan.

- Kent, Marian (1996). The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0714641545.

- Lewis, Bernard (30 August 2001). The Emergence of Modern Turkey (3 ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-513460-5.

- Ishkanian, Armine (2008). Democracy Building and Civil Society in Post-Soviet Armenia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-92922-3.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the stateless nations. 1. A – C. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32109-2. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Reynolds, Michael A. (2011). Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908–1918. Cambridge University Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0521149167.

- Chatterji, James Nikshoy C. (1973). Muddle of the Middle East. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-391-00304-0. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Trumpener, Ulrich (1962). "Turkey's Entry into World War I: An Assessment of Responsibilities". Journal of Modern History. 34 (4): 369–80. doi:10.1086/239180. S2CID 153500703.

- Laçiner, Sedat; Bal, Ihsan (2004). "The Ideological And Historical Roots of Kurdist Movements in Turkey: Ethnicity Demography, Politics". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 10 (3). doi:10.1080/13537110490518282. S2CID 144607707.

- Muller, Jerry Z (March–April 2008), "Us and Them – The Enduring Power of Ethnic Nationalism", Foreign Affairs, Council on Foreign Relations, retrieved 30 December 2008

Further reading

- Öktem, Emre (September 2011). "Turkey: Successor or continuing state of the Ottoman empire?". Leiden Journal of International Law. 24 (3): 561–583. doi:10.1017/S0922156511000252. S2CID 145773201. - published online on 5 August 2011

.jpg.webp)