Separatist movements of Pakistan

There are or have been a number of separatist movements in Pakistan based on ethnic and regional nationalism, that have agitated for independence, and sometimes fighting the Pakistan state at various times during its history.[1] As in many other countries, tension arises from the perception of minority/less powerful ethnic groups that other ethnicities dominate the politics and economics of the country to the detriment of those with less power and money.[2] The government of Pakistan has attempted to subdue these separatist movements,[3] which have included those in Bangladesh, the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) in Balochistan; the "Sindhudesh" movement in Sindh province; "Balawaristan" in Gilgit-Baltistan; Jinnahpur and Muhajir Sooba movement for muhajir immigrants from India.

Influence and success of separatist groups has varied from total, in the case of Bangladesh, which separated from Pakistan in 1971, to marginal, as in the case of the Mohajir Qaumi Movement, which when accused by Pakistani intelligence of wanting an independent state, claimed to only want more autonomy.[4]

Separatist sentiment by opinion poll

The separatist movement in Balochistan is engaged in a low-intensity insurgency against the Government of Pakistan.[5][6]

In 2009, the Pew Research Center conducted a Global Attitudes survey across Pakistan, in which it questioned respondents whether they viewed their primary identity as Pakistani or that of their ethnicity. The sample covered an area representing 90% of the adult population, and included all major ethnic groups.[7] According to the findings, 96% of Punjabis identified themselves first as Pakistanis, as did 92% each of Pashtuns and Muhajirs; 55% of Sindhis chose a Pakistani identification, while 28% chose Sindhi and 16% selected "both equally"; whereas 58% of Baloch respondents chose Pakistani and 32% selected their ethnicity and 10% chose both equally.[7] Collectively, 89% of the sample opted their primary identity as Pakistani.[7] Similarly in 2010, Chatham House conducted an opinion poll in the Pakistani and Indian-administered regions of Kashmir asking respondents if they favoured independence or an accession to either countries; in Azad Kashmir controlled by Pakistan, 50% of respondents voted to join Pakistan, 44% voted for independence, and only 1% voted for accession to India.[8] In the northern region of Gilgit-Baltistan, longstanding local sentiments oppose any merger of the area with Kashmir, and instead demand a constitutional integration with Pakistan.[9][10][11][12]

Bangladesh

Pakistan was established in 1947, from the partition, as a state for Muslims.[13] Its formation was based on the basis of Islamic nationalism.

As part of the Partition of India in 1947, Bengal was partitioned between the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The Pakistani part of Bengal was known as East Bengal until 1955 and thereafter as East-Pakistan following the implementation of the One Unit program. However, rampant corruption within the ranks of the Pakistani government and bureaucracy, economic inequality between the country's two wings caused mainly by a lack of representative government and the government's indifference to the efforts of fierce ethno-nationalistic politicians, like Sheik Mujibur Rahman from East Pakistan, who fought for Bangladeshi independence, resulted in civil war in Pakistan and subsequent separation of East Pakistan as the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Bilateral relations between the two wings grew strained over the lack of official recognition for the Bengali language, democracy, regional autonomy, disparity between the two wings, ethnic discrimination, and the central government's weak and inefficient relief efforts after the 1970 Bhola cyclone, which had affected millions in East Pakistan. These grievances led to several political agitations in East Bengal and ultimately a fight for full independence, which was made possible in 1971 with the assistance of the Indian military.

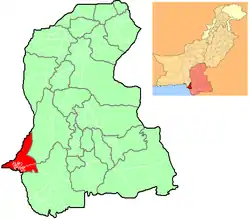

Balochistan

The Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) separatist group was founded by Jumma Khan Marri in 1964 in Damascus, and played an important role in the 1968-1980 insurgency in Pakistani Balochistan and Iranian Balochistan. Mir Hazar Ramkhani, the father of Jumma Khan Marri, took over the group in the 1980s. The Balochistan Liberation Army (also Baloch Liberation Army or Baluchistan Liberation army) (BLA) is a Baloch nationalist militant secessionist organization. However, Jumma Khan Marri ended his opposition and pledged allegiance to Pakistan on 17 February 2018.[14] The stated goals of the organization include the establishment of an independent state of Balochistan separate from Pakistan and Iran. The name Baloch Liberation Army first became public in summer 2000, after the organization claimed credit for a series of bomb attacks in markets and railways lines. The BLA has also claimed responsibility for the systematic ethnic genocide of Punjabis, Pashtuns and Sindhis in Balochistan (about 25,000 as of July 2010) as well as blowing up of gas pipelines.[15][16][17][18][19] Local Balochs have also been targeted by the separatist groups in the province.[20] Brahamdagh Khan Bugti, alleged leader of Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), also asked separatists to conduct ethnic cleansing of Non-Baloch citizens from the province.[21] In 2006, the BLA was declared to be a terrorist organization by the Pakistani and British governments.[22]

However, the insurgency led by the Baloch separatists in the province is on its last leg. Baloch separatists have been losing their leaders and they have been unable to fill their ranks. There is also currently ongoing infighting between the different insurgents groups.[6][23] The last insurgent leader, Balach Marri, was able to keep the different insurgent groups united. However, after his death in Afghanistan,[24][25] infighting broke out between various insurgent groups. The insurgents were unable to replace him. Similarly, Baloch separatist follow Marxism. However, the Marxism ideology died across the world and there is no other ideologies to succeed it. So the founding father of Baloch separatist are dead.[6][26][27] Moreover, attacks on pro-government leaders and politicians who are willing to take part in election has also contributed to the decline in separatist appeal.[6]

The News International reported in 2012 that a Gallup survey conducted for DFID revealed that the majority of Baloch do not support independence from Pakistan. Only 37 percent of Baloch were in favour of independence. Amongst Balochistan's Pashtun population support for independence was even lower at 12 percent. However, a majority (67 percent) of Balochistan's population did favour greater provincial autonomy.[28] Majority of Baloch also don't support separatist groups. They support political parties who use legislature to address their grievances. Experts also claim that most of the nationalists in the province had come to believe that they could fight for their political right within Pakistan.[29]

As of 2018, the Pakistani state was using Islamist militants to crush Balochi separatists.[30] Academics and journalists in the United States have allegedly been approached by Inter-Services Intelligence spies, who threatened them not to speak about the insurgency in Balochistan, as well as human rights abuses by the Pakistani Army, or else their families would be harmed.[31]

By 2020, insurgency by Baluch had been "greatly weakened" by Pakistan counterinsurgency operations including incentives for the militants to lay down their weapons, and by fatigue and rifts among the separatists. In addition, the safe haven for the separatists in Afghanistan was eliminated by the victory of the Taliban in 2021. However, in 2021 the number of terrorist attacks by separatists in Baluchistan "nearly doubled" compared to the previous year.[32]

Sindhudesh

Sindhudesh (Sindhi: سنڌو ديش, literally "Sindhi Country") is an idea of a separate Homeland for Sindhis[33][34] proposed by Sindhi nationalist parties for the creation of a Sindhi state, which would be independent from Pakistan.[1][35] The movement is based in the Sindh region of Pakistan and was conceived by the Sindhi political leader G. M. Syed. A Sindhi literary movement emerged in 1967 under the leadership of Syed and Pir Ali Mohammed Rashdi, in opposition to the One Unit policy, the imposition of Urdu by the central government and to the presence of a large number of Muhajir (Indian Muslim refugees) settled in the province.[36]

However, neither the separatist party nor the nationalist party have ever been able to take centre stage in Sindh. Local Sindhis strongly support Pakistan People Party (PPP). The unparalleled and unhindered success of the PPP in Sindh shows the preference of Sindhis for a constitutional political process over a separatist agenda to resolve their grievances. Similarly public opinion is also not heavily in favour of these parties either. In other words, neither the Sindhi separatists nor the nationalists have significant popular support — certainly not the kind that will make them capable of fuelling a full-scale insurgency. Almost all of the Sindhis have a strong Pakistani identity and prefer to remain part of Pakistan.[37]

In 2012, a Sindhudesh rally was organised by a nationalist party in Karachi, which had a notably low turnout. The nationalist party had claimed that they would gather around million people for their million march. Although, only 3,000 to 4,000 people attended the rally.[38]

In 2020, the Pakistani government banned multiple separatist outfits including the Jeay Sindh Qaumi Mahaz - Aresar group, Sindhudesh Liberation Army, and Sindhudesh Revolutionary Army[39]

Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan

_(claims_hatched).svg.png.webp)

As of 2015, an independence movement exists in Gilgit-Baltistan (called "Balawaristan" by its supporters).[40] Balawaristan National Front (Hameed Group) (BNF-H) led by Abdul Hamid Khan were trying to seek independence of Gilgit-Baltistan from Pakistan. However, Abdul Hamid Khan unconditionally surrendered to Pakistan security officials on 8 February 2019 after being banned for having connections to Indian intelligence agencies. Following his surrender, 14 more members of BNF-H were arrested for their anti-Pakistani activities.[41][42] Since then the fate of BNF-H is unknown. Another organisation by the name of Balawaristan National Front led by Nawaz Khan Naji seeks to declare Gilgit-Balistan an autonomous Region under Administration of Pakistan till Promised pelbicite.[43]

In Pakistan administred Kashmir, no political parties with that do not agree with accession with Pakistan can contest elections.[44]

Sardar Arif Shahid, was a Kashmiri nationalist leader who advocated the independence of Kashmir from both India and Pakistan's rule. He was killed on May 14, 2013 outside his house in Rawalpindi. It was the first time any pro-independence Kashmiri leader was targeted in this way in Pakistan. His supporters allege that he was killed by Pakistan security forces.[45] Within the area, "Custodial torture and intimidation of independence supporters and other activists" has occurred.[3]

In 2010, Chatham House, a London based think tank, did a survey,[46] sponsored by Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, in both Pakistani and Indian administered Kashmir. Based on a sample size of 3,774,[46] it found that Kashmiri's on both sides wanted independence. The survey states, 44% of Kashmiri's in Pakistan administered Kashmir wanted independence.[47]

In October 2019, the People National Alliance organised a rally to free Kashmir from Pakistani rule. As a result of the police trying to stop the rally, 100 people were injured.[48] Large-scale demonstrations have erupted in the region of Gilgit-Baltistan, currently under Pakistani control. Protesters are fervently chanting 'Let's go to Kargil' and expressing a desire to unite with India.[49]

Jinnahpur and Muhajir Sooba

Jinnahpur refers to an alleged plot in Pakistan to form a breakaway autonomous state to serve as a homeland for the Karachi based Urdu-speaking Muhajir community.[50] Mohajirs are immigrants who came to Pakistan from India in the wake of the violence that followed the independence of India in 1947. The alleged name to be given to the proposed breakaway state was "Jinnahpur", named after Mohammed Ali Jinnah. In 1992, the Pakistani military claimed it had found maps of the proposed Jinnahpur state in the offices of the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (now renamed Muttahida Qaumi Movement), despite the party's strong denial of the authenticity of the maps. Despite the party's strong commitment to the Pakistani state, at that time government of Nawaz Sharif chose to use it as the basis for the military operation against the MQM, known as Operation Clean-up.[4]

The Muhajir Sooba (literally meaning 'Immigrant Province') is a political movement which seeks to represent the Muhajir people of Sindh.[51][52] This concept floated as a political bargaining tool by the leader of Muttahida Qaumi Movement, Altaf Hussain for the creation of a Muhajir province for the Muhajir-majority areas of Sindh, which would be independent from Sindh government.

References

- "pakistan-day-jsqm-leader-demands-freedom-for-sindh-and-balochistan". Express Tribune. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress. 2005. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Arch Puddington, Aili Piano, Jennifer Dunham, Bret Nelson, Tyler Roylance (2014). Freedom in the World 2014: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 805. ISBN 9781442247079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The MQM of Pakistan: Between Political Party and Ethnic Movement, Mohammad Waseem, in Political parties in South Asia, ed. Mitra, Enskat & Spiess, pp185

- "Over 300 anti-state militants surrender arms in Balochistan". Dawn News. 9 December 2017.

The largest province of the country by area, Balochistan is home to a low-level insurgency by ethnic Baloch separatists.

- "Balochistan's Separatist Insurgency On The Wane Despite Recent Attack". Gandhara Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberity. 18 April 2019.

- "Pakistani Public Opinion – Chapter 2. Religion, Law, and Society". Pew Research Center. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Bradnock, Robert W. (May 2010). "Kashmir: Path to Peace" (PDF). Chatham House: 19. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Singh, Pallavi (29 April 2010). "Gilgit-Baltistan: A question of autonomy". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

But it falls short of the main demand of the people of Gilgit- Baltistan for a constitutional status to the region as a fifth province and for Pakistani citizenship to its people.

- Shigri, Manzar (12 November 2009). "Pakistan's disputed Northern Areas go to polls". Reuters. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

Many of the 1.5 million people of Gilgit-Baltistan oppose integration into Kashmir and want their area to be merged into Pakistan and declared a separate province.

- Victoria Schofield (23 October 2015). "Kashmir and its regional context". In Shaun Gregory (ed.). Democratic Transition and Security in Pakistan. Routledge. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-1-317-55011-2.

- Rita Manchanda (16 March 2015). SAGE Series in Human Rights Audits of Peace Processes: Five-Volume Set. SAGE Publications. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-93-5150-213-5.

- Ishtiaq Ahmad; Adnan Rafiq (3 November 2016). Pakistan's Democratic Transition: Change and Persistence. Taylor & Francis. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-317-23595-8.

- "Baloch leader distances himself from separatist movement". Dawn News. 20 February 2018.

- "Gunmen kill six labourers in Balochistan: police". Samaa Tv. 4 May 2018.

- "Four Sindhi labourers gunned down in Balochistan". Dawn News. 5 April 2017.

- "BLA kills 10 Sindhi labourers in Gwadar". The Nation. 14 May 2017.

- "Understanding Pakistan's Baloch Insurgency". The Diplomat. 24 June 2015.

- "Abductors kill seven coal miners in Balochistan". Dawn News. 12 July 2012.

- "The End of Pakistan's Baloch Insurgency?". Huffington Post. 11 March 2014.

- "Baloch Liberation Army". Mapping Militant Organizations- web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

Some human rights organizations accuse the BLA of ethnic cleansing because on April 15, 2009 during an interview on AAJ TV, alleged leader Brahamdagh Khan Bugti urged separatist to kill any non-native Balochi residing in Balochistan which allegedly led to the deaths of 500 non-Baloch

- "Pakistan bans 25 militant organisations". DAWN.COM. 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- "Factionalism in the Balochistan Insurgency – An overview". STRATAGEM. 7 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "Balochistan: Insurgency could directly effect the children and women of refugees". BBC News (in Urdu). 12 January 2019.

- "India in Afghanistan". Caravan Magazine. 29 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-10-29.

- "The End of Pakistan's Baloch Insurgency?". Huffington Post. 11 March 2014.

- "Baloch movement stilled by lack of leadership, strategy". First Post. 26 January 2019.

- "37pc Baloch favour independence: UK survey". The News International. 13 August 2012.

- "What's behind the Baloch insurgency in Pakistan?". TRT World. 19 April 2019.

But the majority of the population does not support the hardliners and continues to back local political parties, which want to use legislature to address day-to-day grievances. Experts say most of the nationalists had come to believe that they could fight for political rights within Pakistan.

- Akbar, Malik Siraj (19 July 2018). "In Balochistan, Dying Hopes for Peace". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

Increasing attacks by the Islamic State in Balochistan are connected to Pakistan's failed strategy of encouraging and using Islamist militants to crush Baloch rebels and separatists.

- Mazzetti, Mark; Schmitt, Eric; Savage, Charlie (23 July 2011). "Pakistan Spies on Its Diaspora, Spreading Fear". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

Several Pakistani journalists and scholars in the United States interviewed over the past week said that they were approached regularly by Pakistani officials, some of whom openly identified themselves as ISI officials. The journalists and scholars said the officials caution them against speaking out on politically delicate subjects like the indigenous insurgency in Baluchistan or accusations of human rights abuses by Pakistani soldiers. The verbal pressure is often accompanied by veiled warnings about the welfare of family members in Pakistan, they said.

- ur-Rehman, Zia (5 May 2020). "Rising Violence by Separatists Adds to Pakistan's Lethal Instability". New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- Syed, G. M. Sindhudesh : A Study in its Separate Identity Through the Ages. G.M. Syed Academy. p. These days a pragmatic situation has become dynamically alive in Pakistan. It is the exhilarating political idea of creating a new independent state of Sindh. So the sons of the soil, in full cooperation should increase the momentum for the demand and efforts to create Sindhu Desh with the new Sindhis who have settled down in this land permanently. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "Analysis: Sindhi nationalists stand divided". Dawn. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "JST demands Sindh's independence from Punjab's 'occupation'". Thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- Farhan Hanif Hanif Siddiqi (4 May 2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-136-33696-6. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Aakash Tolani (16 April 2014). "Sindh is not East Pakistan". Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

- "Million march: Jeay Sindh Tehreek gathers 3,000 people, demands a Sindhu Desh". Express Tribune. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Khan, Iftikhar A. (2020-05-12). "JSQM-A, two separatist outfits in Sindh banned". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849046220.

An independence movement seeking to establish Balawaristan also now exists in Gilgit-Baltistan.

- "RAW network busted in GB". The Nation. 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019.

- "Pakistan security forces say they busted subversive network in Gilgit". Times of India. 21 May 2019.

- Ali, Manzoor (29 April 2011). "Gilgit-Baltistan shocker: Nationalist candidate wins Ghizer by-poll – The Express Tribune". Tribune.com.pk. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

Naji said that the federal government should declare Gilgit-Baltistan a province of Pakistan, give its people representation in the National Assembly and Senate, and extend the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to the region

- "Pakistan is no friend of Kashmir, either".

- "Kashmiris protest at killing of Sardar Arif Shahid". BBC News. 16 May 2013.

It is the first time that a pro-independence Kashmiri leader has been targeted in this way in Pakistan. Mr Shahid led the All Parties National Alliance (APNA), which advocates independence from India and Pakistan.

- Bradnock, Robert W. (May 2010). "Kashmir: Paths to Peace" (PDF). Chatham House. Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "In Kashmir, nearly half favour independence". Archived from the original on 2019-09-09. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- Shams, Shamil (23 October 2019). "Why calls for independence are getting louder in Pakistani Kashmir". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Why people of Pakistan-occupied Gilgit-Baltistan are protesting and threatening to merge with India". Firstpost. 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- "Pakistan cracks showing as Mohajir leader appeals to UN, US, India for rescue". The Times of India. 3 August 2015.

- "Altaf for 'Sindh One' and 'Sindh Two'". Dawn.com. Jan 5, 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Z, Ali (January 4, 2014). "New province: Altaf Hussain kicks up a firestorm". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

Further reading

- Mahmud, Ershad (2008), "The Gilgit-Baltistan Reforms Package 2007: Background, Phases and Analysis", Policy Perspectives, Islamabad: Institute of Policy Studies, 5 (1): 23–40