Enosis

Enosis (Greek: Ένωσις, IPA: [ˈenosis], "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist concept of a Greek state that dominated Greek politics following the creation of modern Greece in 1830. The Megali Idea called for the annexation of all ethnic Greek lands, parts of which had participated in the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s but were unsuccessful and so remained under foreign rule.

A widely known example of enosis is the movement within Greek Cypriots for a union of Cyprus with Greece. The idea of enosis in British-ruled Cyprus became associated with the campaign for Cypriot self-determination, especially among the island's Greek Cypriot majority. However, many Turkish Cypriots opposed enosis without taksim, the partitioning of the island between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. In 1960, the Republic of Cyprus was born, resulting in neither enosis nor taksim.

Around then, Cypriot intercommunal violence occurred in response to the different objectives, and the continuing desire for enosis resulted in the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état in an attempt to achieve it. It, however, prompted Turkey into launching the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, which led to partition and the current Cyprus dispute.

History

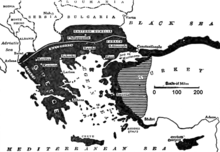

The boundaries of the Kingdom of Greece were originally established at the London Conference of 1832[1] following the Greek War of Independence.[2] The Duke of Wellington wanted the new state to be limited to the Peloponnese[3] because Britain wished to preserve as much of the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire as possible. The initial Greek state included little more than the Peloponnese, Attica and the Cyclades. Its population amounted to less than 1 million, with three times as many ethnic Greeks living outside it, mainly in Ottoman territory.[4] Many of them aspired to be incorporated in the kingdom, and movements among them calling for enosis (union) with Greece, often achieved popular support. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire, Greece expanded with a number of territorial gains.

The Ionian Islands had been placed under British protection as a result of the Treaty of Paris in 1815,[5] but once Greek independence had been established after 1830, the islanders began to resent foreign colonial rule and to press for enosis. Britain transferred the islands to Greece in 1864.

Thessaly remained under Ottoman control after the formation of the Kingdom of Greece. Although parts of the territory had participated in the initial uprisings in the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the revolts had been swiftly crushed. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, Greece remained neutral as a result of assurances by the great powers that her territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire would be considered after the war. In 1881, Greece and the Ottoman Empire signed the Convention of Constantinople, which created a new Greco-Turkish border that Incorporated most of Thessaly into Greece.

Crete rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866-69 and used the motto "Crete, Enosis, Freedom or Death". The Cretan State was established after the intervention of the Great Powers, and Cretan union with Greece occurred de facto in 1908 and de jure in 1913 by the Treaty of Bucharest.

An unsuccessful Greek uprising in Macedonia against Ottoman rule had taken place during the Greek War of Independence. There was a failed rebellion in 1854 that aimed to unite Macedonia with Greece.[6] The Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 after the Russo-Turkish War awarded nearly all of Macedonia to Bulgaria. That resulted in the 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion and the reversal of the award at the Treaty of Berlin (1878), leaving the territory in Ottoman hands. Then followed the protracted Macedonian Struggle between Greeks and Bulgarians in the region, the resultant guerrilla war not coming to an end until the revolution of Young Turks in July 1908. Bulgarian and Greek rivalries over Macedonia became part of the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, with the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest awarding Greece large parts of Macedonia, including Thessaloniki. The Treaty of London (1913) awarded southern Epirus to Greece, the Epirus region having rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Epirus Revolt of 1854 and the Epirus Revolt of 1878.

In 1821, several parts of Western Thrace rebelled against Ottoman rule and participated in the Greek War of Independence. During the Balkan Wars, Western Thrace was occupied by Bulgarian troops, and in 1913, Bulgaria gained Western Thrace under the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest. After World War I, Western Thrace was withdrawn from Bulgaria under the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and temporarily managed by the Allies before being it was given to Greece at the San Remo Conference in 1920.

After World War I, Greece began the Occupation of Smyrna and of surrounding areas of Western Anatolia in 1919 at the invitation of the victorious Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The occupation was given official status in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, with Greece being awarded most of Eastern Thrace and a mandate to govern Smyrna and its hinterland.[7] Smyrna was declared a protectorate in 1922, but the attempted enosis failed since the new Turkish Republic prevailed in the resulting Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, when most Anatolian Christians who had not already fled during the war were forced to relocate to Greece in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

Most of the Dodecanese Islands were slated to become part of the new Greek state in the London Protocol of 1828, but when Greek independence was recognised in the London Protocol of 1830, the islands were left outside the new Kingdom of Greece. They were occupied by Italy in 1912 and held until World War II, when they became a British military protectorate. The islands were formally united with Greece by the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy, despite objections from Turkey, which also desired them.

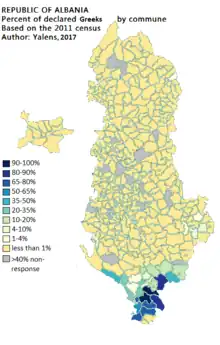

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed in 1914 by ethnic Greeks in Northern Epirus, the area having been incorporated into Albania after the Balkan Wars. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916 and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916,[8] but in 1917 Greek forces were driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania.[9] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece, but Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War made the area revert to Albanian control.[10] Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack let the Greek army briefly hold Northern Epirus for a six-month period until the German invasion of Greece in 1941. Tensions between Greece and Albania remained high during the Cold War, but relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between both countries.[8]

In modern times, apart from Cyprus, the call for enosis is most often heard among part of the Greek community living in southern Albania.[11]

Cyprus

Inception

In 1828, the first President of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias, called for the union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place.[12] Cyprus was at that time part of the Ottoman Empire. At the 1878 Congress of Berlin the administration of Cyprus was transferred to Britain,[13] and upon Garnet Wolseley's arrival as the first high-commissioner in July the Archbishop of Kition requested that Britain transfer the administration of Cyprus to Greece.[14] Britain annexed Cyprus in 1914.

The death of Limassol–Paphos MP Christodoulos Sozos during the course of the Battle of Bizani during the First Balkan War, left a lasting mark on the Enosis movement and was one of its most important events before the 1931 Cyprus revolt. Greek schools and courts suspended their activities, and a court in Nicosia also raised a flag in honour of Sozos, thus breaking the law since Britain had maintained a neutral stance in the conflict. Mnemosyna were held in dozens of villages across Cyprus, as well as in Cypriot communities in Athens, Egypt and Sudan. Greek Cypriot newspapers were swept with nationalist fervor comparing Sozos with Pavlos Melas. A photo of Sozos was placed in the Hellenic Parliament.[15][16]

Britain offered to cede the island to Greece in 1915 in return for Greece joining the allies in World War I, but the offer was refused.[17] Turkey relinquished all claims to Cyprus in 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne, and the island became a British Crown colony in 1925.[18] In 1929, a Greek Cypriot delegation was sent to London to request enosis but received a negative response.[19] After anti-British riots in 1931, the desire for self-government within the British Commonwealth developed, but the movement for enosis became dominant.[20]

The enosis movement was the outgrowth of nationalist awareness among Greek Cypriots (around 80%[21] between 1882 and 1960), coupled with the growth of the anticolonial movement throughout the British Empire after World War II. In fact, the anticolonial movement in Cyprus was identified with the enosist movement, which was, in the minds of the Hellenic population of Cyprus, the only natural outcome of the liberation of Cypriots from Ottoman rule and later British rule. A string of British proposals for local autonomy under continued British suzerainty were roundly rejected.

1940s and 1950s

In the 1950s, the influence of the Greek Orthodox Church of Cyprus over the education system resulted in the ideas of Greek nationalism and enosis being promoted in Greek Cypriot schools. School textbooks portrayed Turks as the enemies of Greeks, and students took an oath of allegiance to the Greek flag. The British authorities attempted to counter that by publishing an intercommunal periodical for students and by suspending the Cyprus Scouts Association for its Greek nationalist tendencies.[22]

In December 1949, the Cypriot Orthodox Church asked the British colonial government to put the enosis question to a referendum on the basis of the right of the Cypriots' for self-determination. Even though the British had been an ally of Greece during World War II and had recently supported the Greek government during the Greek Civil War, the British colonial government refused.

In 1950, Archbishop Spyridon of Athens led the call for Cypriot enosis in Greece.[23] The Church was a strong supporter of enosis and organised a plebiscite, the Cypriot enosis referendum, which was held on 15 and 22 January 1950; only Greek Cypriots could vote. Open books were placed in churches for those over 18 to sign and to indicate whether they supported or opposed enosis. The majority in support of enosis was 95.7%.[24][25] Later, there were accusations that the local Greek Orthodox church had told its congregation that not to vote for enosis would have meant excommunication from the church.[26][27]

After the referendum, a Greek Cypriot deputation visited Greece, Britain and the United Nations to make its case, and Turkish Cypriots and student and youth organisations in Turkey protested the plebiscite. In the event, neither Britain nor the UN was persuaded to support enosis.[28] In 1951, a report was produced by the British government's Smaller Territories Enquiry into the future of the British Empire's smaller territories, including Cyprus. It concluded that Cyprus should never be independent from Britain. That view was strengthened by Britain's withdrawal of its Suez Canal base in 1954 and the transfer of its Middle East Headquarters to Cyprus.[17] In 1954, Greece made its first formal request to the UN for the implementation of "the principle of equal rights and of self-determination of the peoples", in the case of the Cypriot population. Until 1958, four other requests to the United Nations were made unsuccessfully by the Greek government.[29]

In 1955, the resistance organisation EOKA started a campaign against British rule to bring about enosis with Greece. The campaign lasted until 1959,[28] when many argued that enosis was politically unfeasible because of the strong minority of Turkish Cypriots and their increasing assertiveness. Instead, the creation of an independent state with elaborate powersharing arrangements among both communities was agreed upon in 1960, and the fragile Republic of Cyprus was born.

After independence

The idea of union with Greece was not immediately abandoned, however. During the campaign for the 1968 presidential elections, Cypriot President Makarios III said that enosis was "desirable" but that independence was "possible".

In the early 1970s, the idea of enosis remained attractive to many Greek Cypriots, and Greek Cypriot students condemned Makarios's support for an independent unitary state. In 1971 the pro-enosis paramilitary group EOKA B was formed, and Makarios declared his opposition to the use of violence to achieve enosis. EOKA B began a series of attacks against the Makarios government, and in 1974, the Cypriot National Guard organised a military coup against Makarios that was supported by the Greek government under the control of the Greek military junta of 1967–1974. Rauf Denktaş, the Turkish Cypriot leader, called for military intervention by the United Kingdom and Turkey to prevent enosis. Turkey acted unilaterally, and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus began. Turkey has since occupied Northern Cyprus.[20]

The events of 1974 caused the geographic partition of Cyprus and massive population transfers. The subsequent events seriously undermined the enosis movement. The departure of Turkish Cypriots from the areas that remained under effective control of Cyprus resulted in a homogeneous Greek Cypriot society in the southern two thirds of the island. The remaining third of the island is majority Turkish Cypriot, and increasing numbers of Turkish nationals have been migrating there from Turkey.

In 2017 the Cypriot Parliament passed a law to allow for the celebration of the 1950 Cypriot enosis referendum in Greek Cypriot government schools.[30]

North Epirus

The history of Northern Epirus in the period 1913-1921 was marked by the desire of the local Greek element for union with the Kingdom of Greece, as well as the redemptive desire of Greek politics to annex this region, which was eventually awarded to the Albanian Principality.

During the First Balkan War, Northern Epirus, which hosted a significant minority of Orthodox speakers who spoke either Greek or Albanian, was, at the same time as South Epirus, under the control of the Greek army, which had previously repelled Ottoman forces. Greece wanted to annex these territories. However, Italy and Austria-Hungary opposed this, while the Treaty of Florence of 1913 granted Northern Epirus to Albania's newly formed Principality, the majority of whose inhabitants were Muslims. Thus, the Greek army withdrew from the area, but the Christians of Epirus, denying the international situation, decided, with the secret support of the Greek state, to create an autonomous regime, based in Argyrokastro (Albanian: Gjirokastër).

Given Albania's political instability, the autonomy of Northern Epirus was finally ratified by the Great Powers with the signing of the Protocol of Corfu on May 17, 1914. The agreement did recognize the special status of the Epirotes and their right to self-determination. under the legal authority of Albania. However, the agreement never materialized, as the Albanian government collapsed in August, and Prince William of Wied, who was appointed leader of the country in February, returned to Germany in September.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, in October 1914, the Kingdom of Greece recaptured the region. However, the ambiguous attitude of the Central Powers on Greek issues during the Great War, led France and Italy to the joint occupation of Epirus in September 1916. At the end of World War I, however, the Agreement of Titoni with Venizelos foresaw the annexation of the region to Greece. Eventually, Greece's military involvement with Mustafa Kemal's Turkey worked in the interest of Albania, which permanently annexed the region on 9 November 1920.

Smyrna

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the Ottoman Empire. As part of the Treaty of London (1915), by which Italy left the Triple Alliance (with Germany and Austria-Hungary) and joined France, Great Britain and Russia in the Triple Entente, Italy was promised the Dodecanese and, if the partition of the Ottoman Empire were to occur, land in Anatolia including Antalya and surrounding provinces presumably including Smyrna.[33] But in later 1915, as an inducement to enter the war, British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey in private discussion with Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek Prime Minister at the time, promised large parts of the Anatolian coast to Greece, including Smyrna.[33] Venizelos resigned from his position shortly after this communication, but when he had formally returned to power in June 1917, Greece entered the war on the side of the Entente.[34]

On 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Entente powers and the Ottoman Empire ending the Ottoman front of World War I. Great Britain, Greece, Italy, France, and the United States began discussing what the treaty provisions regarding the partition of Ottoman territory would be, negotiations which resulted in the Treaty of Sèvres. These negotiations began in February 1919 and each country had distinct negotiating preferences about Smyrna. The French, who had large investments in the region, took a position for territorial integrity of a Turkish state that would include the zone of Smyrna. The British were at loggerheads over the issue with the War Office and India Office promoting the territorial integrity idea and Prime Minister David Lloyd George and the Foreign Office, headed by Lord Curzon, opposed to this suggestion and wanting Smyrna to be under separate administration.[35] The Italian position was that Smyrna was rightfully their possession and so the diplomats would refuse to make any comments when Greek control over the area was discussed.[36] The Greek government, pursuing Venizelos' support for the Megali Idea (to bring areas with a majority Greek population or with historical or religious ties to Greece under the control of the Greek state) and supported by Lloyd George, began a large propaganda effort to promote their claim to Smyrna including establishing a mission under the foreign minister in the city.[36] Moreover, the Greek claim over the Smyrna area (which appeared to have a clear Greek majority, although exact percentages varied depending on the sources) were supported by Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points which emphasized the right to autonomous development for minorities in Anatolia.[37] In negotiations, despite French and Italian objections, by the middle of February 1919 Lloyd George shifted the discussion to how Greek administration would work and not whether Greek administration would happen.[35] To further this aim, he brought in a set of experts, including Arnold J. Toynbee, to discuss how the zone of Smyrna would operate and what its impacts would be on the population.[36] Following this discussion, in late February 1919, Venezilos appointed Aristeidis Stergiadis, a close political ally, the High Commissioner of Smyrna (appointed over political riser Themistoklis Sofoulis).[36]

In April 1919, the Italians landed and took over Antalya and began showing signs of moving troops towards Smyrna.[35] During the negotiations at about the same time, the Italian delegation walked out when it became clear that Fiume (Rijeka) would not be given to them in the peace outcome.[33] Lloyd George saw an opportunity to break the impasse over Smyrna with the absence of the Italian delegation and, according to Jensen, he "concocted a report that an armed uprising of Turkish guerrillas in the Smyrna area was seriously endangering the Greek and other Christian minorities."[33] Both to protect local Christians and also to limit increasing Italian action in Anatolia, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson supported a Greek military occupation of Smyrna.[33] Although Smyrna would be occupied by Greek troops, authorized by the Allies, the Allies did not agree that Greece would take sovereignty over the territory until further negotiations settled this issue.[33] The Italian delegation acquiesced to this outcome and the Greek occupation was authorized.

Turkish capture of Smyrna

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds.[33] Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian population occurred immediately after the takeover.[38][39] Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged.[40] Culpability for the fire is blamed on all ethnic groups and clear blame remains elusive.[33] On the Turkish side - but not among Greeks - the events are known as the "Liberation of İzmir".

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey resulting in migration to Greece and elsewhere.[36]

Ionian Islands

Under the Treaty between Great Britain and [Austria, Prussia and] Russia, respecting the Ionian Islands (signed in Paris on 5 November 1815), as one of the treaties signed during the Peace of Paris (1815), Britain obtained a protectorate over the Ionian Islands, and under Article VIII of the treaty the Austrian Empire was granted the same trading privileges with the Islands as Britain.[41] As agreed in Article IV of the treaty a "New Constitutional Charter for the State" was drawn up and was formalised with the ratification of the "Maitland constitution" on 26 August 1817, which created a federation of the seven islands, with Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Maitland its first "Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands".

A few years later Greek nationalist groups started to form. Although their energy in the early years was directed to supporting their fellow Greek revolutionaries in the revolution against the Ottoman Empire, they switched their focus to enosis with Greece following their independence. The Party of Radicals (Greek: Κόμμα των Ριζοσπαστών) founded in 1848 as a pro-enosis political party. In September 1848 there were skirmishes with the British garrison in Argostoli and Lixouri on Kefalonia, which led to a certain level relaxation in the enforcement of the protectorate's laws, and freedom of the press as well. The island's populace did not hide their growing demands for enosis, and newspapers on the islands frequently published articles criticising British policies in the protectorate. On 15 August in 1849, another rebellion broke out, which was quashed by Henry George Ward, who proceeded to temporarily impose martial law.[42]

On 26 November 1850, the Radical MP John Detoratos Typaldos proposed in the Ionian parliament the resolution for the enosis of the Ionian Islands with Greece which was signed by Gerasimos Livadas, Nadalis Domeneginis, George Typaldos, Frangiskos Domeneginis, Ilias Zervos Iakovatos, Iosif Momferatos, Telemachus Paizis, Ioannis Typaldos, Aggelos Sigouros-Dessyllas, Christodoulos Tofanis. In 1862, the party split into two factions, the "United Radical Party" and the "Real Radical Party". During the period of British rule, William Ewart Gladstone visited the islands and recommended their reunion with Greece, to the chagrin of the British government.

On 29 March 1864, representatives of Great Britain, Greece, France, and Russia signed the Treaty of London, pledging the transfer of sovereignty to Greece upon ratification; this was meant to bolster the reign of the newly installed King George I of Greece. Thus, on 28 May, by proclamation of the Lord High Commissioner, the Ionian Islands were united with Greece.[43]

See also

Notes

- "Ethnic Greek minority groups had encouraged their members to boycott the census, affecting measurements of the Greek ethnic minority and membership in the Greek Orthodox Church."[31]

- "Portions of the census dealing with religion and ethnicity have grabbed much of the attention, but entire parts of the census might not have been conducted according to the best international practices, Albanian media reports..."[32]

References

- "On This Day In History: Independence Of Greece Is Recognized By The Treaty Of London – On May 7, 1832". Ancient Pages. 7 May 2016.

- Anagnostopoulos, Nikodemos (2017). Orthodoxy and Islam: Theology and Muslim–Christian Relations in Modern Greece and Turkey. Routledge. ISBN 9781315297910.

- Cooke, Tim (2010). The New Cultural Atlas of the Greek World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 174. ISBN 9780761478782.

- Hupchick, D (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Springer. p. 223. ISBN 9780312299132.

- Grotke, Kelly L.; Prutsch, Markus Josef, eds. (2014). Constitutionalism, Legitimacy, and Power: Nineteenth-century Experiences. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780198723059.

- Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse, 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 249–252. ISBN 9783515076876.

- Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe. Vol. 2. p. 888. ISBN 9781576078006.

- Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (ed.). The new Albanian migrations. Sussex Academic Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781903900789.

- Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- Stein, Jonathan (2000). The politics of national minority participation in post-communist Europe : state-building, democracy, and ethnic mobilization. Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe. p. 180. ISBN 9780765605283.

- William Mallinson, Bill Mallinson (2005). Cyprus: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 10. ISBN 9781850435808.

ISBN 1-85043-580-4" "In 1828, modern Greece's first president, Count Kapodistria, called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and various minor uprising took place.

- Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780810862982.

- Mirbagheri (2009), p. 57.

- Papapolyviou 1996, pp. 186–193, 340.

- Klapsis 2013, pp. 765–767.

- McIntyre, W. David (2014). Winding Up the British Empire in the Pacific Islands. Oxford History of the British Empire. OUP. p. 72. ISBN 9780198702436.

- Goebl, Hans; et al., eds. (2008). Kontaktlinguistik. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft. Vol. 12. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1579. ISBN 9783110203240.

- Goktepe, Cihat (2013). British Foreign Policy Towards Turkey, 1959-1965. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 9781135294144.

- The Middle East and North Africa 2003. Regional surveys of the world (49th ed.). Psychology Press. 2002. pp. 242–5. ISBN 9781857431322.

- "Cyprus - Population". Country-data.com. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- Lange, Matthew (2011). Educations in Ethnic Violence: Identity, Educational Bubbles, and Resource Mobilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–5. ISBN 978-1139505444.

- Stephanidēs, Giannēs D. (2007). Stirring the Greek Nation: Political Culture, Irredentism and Anti-Americanism in Post-war Greece, 1945-1967. Ashgate Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 9780754660590.

- Goktepe 2013, pp. 92–3.

- Zypern, 22. Januar 1950 : Anschluss an Griechenland Direct Democracy

- "ΕΝΩΤΙΚΟ ΔΗΜΟΨΗΦΙΣΜΑ 15-22/1/1950 (in Greek, includes image of a signature page)". Cyprus.novopress.info. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- "Κύπρος: το ενωτικό δημοψήφισμα που έγινε με υπογραφές (in Greek)". Hellas.org. 1967-04-21. Archived from the original on 3 March 2001. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- Goktepe 2013, p. 93.

- Emis i Ellines- Polemiki istoria tis Synhronis Elladas ("Greeks- War History of Modern Greece"), Skai Vivlio press, 2008, chapter by nikos Papanastasiou "The Cypriot Issue", p. 125, 142

- "Turkey slams Greek Cyprus' Enosis move". Hürriyet Daily News. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "International Religious Freedom Report for 2014: Albania" (PDF). www.state.gov. United States, Department of State. p. 5. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "Final census findings lead to concerns over accuracy". Tirana Times. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-12-26.

- Jensen, Peter Kincaid (1979). "The Greco-Turkish War, 1920–1922". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 4. 10 (4): 553–565. doi:10.1017/s0020743800051333. S2CID 163086095.

- Finefrock, Michael M. (1980). "Atatürk, Lloyd George and the Megali Idea: Cause and Consequence of the Greek Plan to Seize Constantinople from the Allies, June–August 1922". The Journal of Modern History. 53 (1): 1047–1066. doi:10.1086/242238. S2CID 144330013.

- Montgomery, A. E. (1972). "The Making of the Treaty of Sèvres of 10 August 1920". The Historical Journal. 15 (4): 775–787. doi:10.1017/S0018246X0000354X. S2CID 159577598.

- Llewellyn-Smith, Michael (1999). Ionian Vision : Greece in Asia Minor, 1919–1922 (New edition, 2nd impression ed.). London: C. Hurst. p. 92. ISBN 9781850653684.

- Myhill, John (2006). Language, religion and national identity in Europe and the Middle East : a historical study. Amsterdam [u.a.]: Benjamins. p. 243. ISBN 9789027227119.

- Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (2013). Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 351. ISBN 9781134259588. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

Kemal's triumphant entry into Smyrna... as Greek and Armenian inhabitants were raped, mutilated, and murdered.

- Abulafia, David (2011). The Great Sea : A Human History of the Mediterranean. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780195323344. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

As the refugees crowded into the city, massacres, rape and looting, mainly but not exclusively by the irregulars, became the unspoken order of the day... Finally, the streets and houses of Smyrna were soaked in petrol... and on 13 September the city was set alight.

- Stewart, Matthew (2003-01-01). "It Was All a Pleasant Business: The Historical Context of 'On the Quai at Smyrna'". The Hemingway Review. 23 (1): 58–71. doi:10.1353/hem.2004.0014. S2CID 153449331.

- Hammond, Richard James (1966). Portugal and Africa, 1815–1910 : a study in uneconomic imperialism. Stanford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-8047-0296-9.

- British Occupation

- Hertslet, Edward. The map of Europe by treaty (PDF). p. 1609. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

Sources

- Klapsis, Antonis (2009). "Between the Hammer and the Anvil. The Cyprus Question and the Greek Foreign Policy from the Treaty of Lausanne to the 1931 Revolt". Modern Greek Studies Yearbook. University of Minnesota. 24: 127–140. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Klapsis, Antonis (2013). "The Strategic Importance of Cyprus and the Prospect of Union with Greece, 1919–1931: The Greek Perspective". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 41 (5): 765–782. doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.789275. S2CID 161803453.

- Papapolyviou, Petros (1996). Η Κύπρος και οι Βαλκανικοί Πόλεμοι: Συμβολή στην Ιστορία του Κυπριακού Εθελοντισμού [Cyprus and the Balkan Wars: A Contribution to the History of Cypriot Volunteerism] (Doctoral Dissertation) (in Greek). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 1–407. doi:10.12681/eadd/8976. hdl:10442/hedi/8976. Retrieved 6 September 2017.