Cave of Aurignac

The Cave of Aurignac is an archaeological site in the commune of Aurignac, Haute-Garonne department in southwestern France. Sediment excavation and artefact documentation since 1860 confirm the idea of the arrival and permanent presence of European early modern humans during the Upper Palaeolithic.[1] The eponymous location represents the type site of the Aurignacian, the earliest known culture attributed to modern humans in western Eurasia. Assemblages of Aurignacian tool making tradition can be found in the cultural sediments of numerous sites from around 45,000 years BP to around 26,000 years BP.[2] In recognition of its significance for various scientific fields and the 19th-century pioneering work of Édouard Lartet the Cave of Aurignac was officially declared a national Historic Monument of France by order of May 26, 1921.[3]

Grotte d'Aurignac | |

Entrance porch of the Aurignac shelter | |

Cave of Aurignac location in France  Cave of Aurignac (France) | |

| Alternative name | Grotte de Rodes |

|---|---|

| Location | Near the commune of Aurignac, Haute-Garonne department |

| Region | southwestern France on the northern side the Pyrenees |

| Coordinates | 43°13′21″N 0°51′55″E |

| Height | 11.8 m (39 ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Thanetian limestone |

| Periods | Upper Palaeolithic, Chalcolithic |

| Cultures | Aurignacian |

| Associated with | European early modern humans |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | since 1860 |

| Archaeologists | Édouard Lartet, Fernand Lacorre, Louis Meroc |

| Public access | yes |

Location

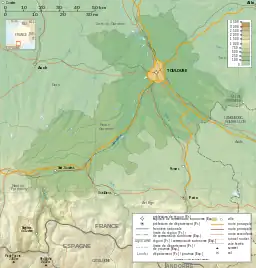

The Aurignac limestone grotto is located in the Aurignac commune, approximately 1.5 km (0.93 mi) northwest of the town centre, on the southern side of the Rodes rivulet valley, a tributary of the Louge river just north of the Pyrenees.[4]

History

In 1852, several years before the advent of paleoanthropology as a scientific discipline, local worker Jean Baptist Bonnemaison searched the embankment and the platform in front of the cave out of curiosity, where he found some prehistoric tools. However, he also discovered seventeen human skeletons inside the cave, which had been closed in by a sandstone plate. These, reportedly, were quickly re-buried in the local parish cemetery upon the request of Dr. Amiel, the communal mayor at the time. Their age and origin remain unclear as they never underwent scientific examination and are now considered lost. Neither Édouard Lartet in 1860 nor Fernand Lacorre in 1938 were able to locate the 1852 burial site.[5]

Pioneer paleontologist Édouard Lartet lead the first excavation from 1860 to 1863 and recovered advanced tools, such as finely cut flints, struck from prepared core and variously worked bones and reindeer antlers, a great number of fossilized human bone and ceramic fragments, although the latter had confirmedly been buried during the Chalcolithic (around 6,000 to 4,000 years BP).[6]

Lartet started to search the area, that had contained the 17 skeletons and discovered the fossilized remains of several species of carnivores, such as the Cave hyena, Cave bear and Vulpes (red fox) species, numerous herbivore species like mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, horse, bison and reindeer, that are kept in the collections of the Musée de l'Homme.[7] At the very base in a thick black layer that contained large quantities of ash and charcoal, he unearthed characteristic sharpened flint tools and worked bones and antlers. Lartet concluded in his 1861 publication New Researches on the Coexistence of Man and of the Great Fossil Mammifers characteristic of the Last Geological Period, that these local early humans must have been contemporaries of the extinct animal species. From 1938 to 1939, Fernand Lacorre and his wife resumed the excavations and unearthed more large amounts of fossilized bones of over 30 species of animals.[8]

Stratigraphy

During subsequent excavations an accurate sequence of three distinct stratae was established.

- The lowest and oldest layer with dark sediments and artefacts attributed to early human occupation (about 35,000 years ago), during which time the site served as a shelter and permanent camp.[6]

Lartet, one of the first scholars to ever produce some form of prehistoric timeline in his documentation, developed his system primarily along the faunal fossil sequence. A method, that proved to be not popular and Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet's more serviceable system of Paleolithic chronology based on the evolution of human tool sets, was widely accepted during the following decades. However, the name Aurignacian in reference to the famous layer mentioned above was assigned only during the early 20th century by Henri Breuil.[8]

- A central layer, which contained a great number of fossilized bones of herbivorous and carnivorous wildlife (after 35,000 years ago).

- The remains and sediments of a common burial place, used during the Chalcolithic, that had been sealed by a sandstone slab and might have included the 17 individuals discovered in 1852 by Bonnemaison[9]

Later research

In 1961, a team under Louis Meroc successfully managed to dig at a site located 30 m (98 ft) from the first cave explored by Lartet. The new site, Aurignac 2, is characterized by the presence of large collapsed blocks. Tools found are mainly careened scrapers, more rarely retouched blades and no chisels. They all come without exception from flint benches (deposits) less than 1 km (0.62 mi) to the east.[9]

Louis Meroc wrote in 1963: "The site of Aurignac 2 was inhabited before the collapse of the first cave, which was certainly only a small appendage of a much larger set of shelters. Based on the current state of knowledge, we assume, that the caves of Aurignac have, apart from the Aurignacian settlers, been unknown to later Paleolithic populations." [9]

Objects found in the Cave of Aurignac, formerly preserved in the National Museum of Archeology and the Museum of Toulouse, are now on display at the Museum Forum of the Aurignac in Aurignac town, which opened its doors to the public in October 2014.[10]

See also

External links

References

- Koehl, Dan. "The Cro Magnon man (Homo sapiens sapiens) Anatomically Modern or Early Modern Humans". elephant.se. Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- John J. Shea (28 February 2013). Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-1-139-61938-7.

- Base Mérimée: PA00094268, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- "Grotte d'Aurignac - Cave or Rock Shelter in France in Midi:Haute-Garonne". Megalithic Portal. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "Le site préhistorique d'AURIGNAC". Club de géologie de Tournefeuille. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- François Bon, Sandrine Costmagno, Nicolas Valdeyron. "HUNTING CAMPS IN PREHISTORY - An apparent absence of Aurignacian "hunting camps"" (PDF). LABORATOIRE TRAVAUX ET RECHERCHES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES SUR LES CULTURES, LES ESPACES ET LES SOCIÉTÉS. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Rediscovering the bones of the Aurignac Cave". Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. October 9, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- François Bon. "L'Aurignacien à l'ombre des Pyrénées / Das Aurignacien im schatten der Pyrenäen". Megalithic Portal. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Recherche grotte L'abri d'Aurignac". Club de géologie de Tournefeuille. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "MUSEUM FORUM OF THE AURIGNACIAN". CARP - PREHISTORIC ROCK ART TRAILS. Retrieved February 28, 2019.