Battle of Abbeville

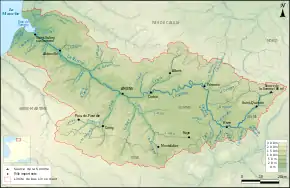

The Battle of Abbeville took place from 27 May to 4 June 1940, near Abbeville during the Battle of France in the Second World War. On 20 May, the 2nd Panzer Division advanced 56 mi (90 km) to Abbeville on the English Channel, overran the 25th Infantry Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division and captured the town at 8:30 p.m. Only a few British survivors managed to retreat to the south bank of the Somme and at 2:00 a.m. on 21 May, the III Battalion, Rifle Regiment 2 reached the coast, west of Noyelles-sur-Mer.

| Battle of Abbeville | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of France, the Second World War | |||||||

Situation map 21 May – 6 June 1940 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Maxime Weygand Charles de Gaulle Victor Fortune |

Oskar Blümm Erich von Manstein | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

c. 2,000 killed or captured c. 210 AFVs destroyed or captured | 57th Infantry Division: 1,000 casualties including about 300 POW | ||||||

The 1st Armoured Division (Major-General Roger Evans) arrived in France from 15 May without artillery, short of an armoured regiment and the infantry of the 1st Support Group, which had been diverted to Calais. From 27 May to 4 June, attacks by the Franco-British force south of the Abbeville bridgehead, held by the 2nd Panzer Division, then the 57th Infantry Division, recaptured about half of the area; the Allied forces lost many of their tanks and the Germans much of their infantry, some units running back over the River Somme. On 5 June, the divisions of the German 4th Army attacked out of the bridgeheads south of the Somme and pushed back the Franco-British divisions opposite, which had been much depleted by their counter-attacks, to the Bresle with many casualties.

In 1953, the British official historian, Lionel Ellis, wrote that the Allies lacked battlefield co-ordination, which contributed to the Allied failure to defeat the Germans and magnified the cost of lack of preparation and underestimation of the German defences south of the Somme. In 2001, Caddick-Adams also wrote of the chronic lack of battlefield communication within and between the British and French divisions, which was caused by a shortage of radios and led to elementary and costly tactical errors. The lack of communication continued after reinforcement by the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (Major-General Victor Fortune) and French armoured and infantry divisions. The Germans had committed substantial forces to the bridgeheads, despite the operations in the north, that culminated in the Dunkirk evacuation (26 May – 3 June). The Somme crossings at Abbeville and elsewhere were still available on 5 June, for Fall Rot (Case Red), the final German offensive, which brought about the defeat of France.

Background

Battle of France

After the Phoney War, the Battle of France began on 10 May 1940 when the German armies in the west commenced Fall Gelb. The German Army Group B invaded the Netherlands and advanced westwards. General Maurice Gamelin, the Supreme Allied Commander, initiated the Dyle Plan (Plan D) and invaded Belgium to close up to the Dyle river with the French First and Seventh armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The plan relied on the Maginot Line fortifications along the German–French border to economise on troops and enable a mobile battle to be fought in Belgium. The Breda variant of Plan D required the Seventh Army to advance swiftly into the south-western Netherlands, to link with the Dutch army but the Germans advanced through most of the Netherlands before the French forces arrived. The attack into the Low Countries by Army Group B was a decoy, intended to attract the bulk of the most powerful French and British forces, while Army Group A advanced through the Ardennes, further to the south, against second-rate French reserve divisions. The Germans crossed the Meuse at Sedan on 14 May, far too quickly for the Allies to react, then attacked down the Somme valley.[1]

On 19 May, the 7th Panzer Division (Major-General Erwin Rommel) attacked Arras but was repulsed and during the evening the SS Division Totenkopf (Gruppenführer Theodor Eicke) arrived on the left flank of the 7th Panzer Division. The 8th Panzer Division, further on the left, reached Hesdin and Montreuil, the 6th Panzer Division captured Doullens after a day-long battle with the 36th Infantry Brigade of the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division; advanced units pressed on to Le Boisle. On 20 May, the 2nd Panzer Division covered 56 mi (90 km) straight to Abbeville on the English Channel. Luftwaffe attacks on Abbeville increased, the Somme bridges were bombed and at 4:30 p.m. a party from the 2/6th Queens of the 25th Infantry Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, ran into a German patrol and managed to report that the Germans had got between the 2/6th and 2/7th Queens. The British infantry were short of equipment and ammunition and were soon ordered to retreat over the river; the 1/5th and 2/7th Queens found the bridges had been destroyed in the bombing. The Germans captured the town at 8:30 p.m. and only a few British survivors managed to retreat to the south bank of the Somme.[2][lower-alpha 1] At 2:00 a.m. on 21 May, the III Battalion, Rifle Regiment 2 reached the coast west of Noyelles-sur-Mer.[4]

The 1st Panzer Division captured Amiens and established a bridgehead on the south bank, over-running the 7th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment of the 37th (Royal Sussex) Infantry Brigade. Of the 701 men in the battalion, only 70 survived to be captured but the operation deterred the Germans from probing further.[5] The 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division and 23rd (Northumbrian) Division had been destroyed, the area between the Scarpe and the Somme had been captured, the British lines-of-communication had been cut and the Channel Ports were vulnerable to capture. The Army Group A war diarist wrote,

Now that we have reached the coast at Abbeville, the first stage of the offensive has been achieved.... The possibility of an encirclement of the Allied armies' northern group is beginning to take shape.

At 8:30 a.m., RAF Air Component Hawker Hurricane pilots reported a German column at Marquion on the Canal du Nord and others further south. Fires were seen in Cambrai, Douai and Arras which the Luftwaffe had bombed but the Air Component was moving back to bases in England. Communication between the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) in the south, the remaining Air Component units in the north and the Air Ministry was disorganised; the squadrons in France had constantly to move bases and operate from unprepared airfields with poor telephone connexions. The AASF was cut off from the BEF; the Air Ministry and England-based squadrons were too far away for close co-operation. Two squadrons of bombers in England reached the column seen at 11:30 a.m. and bombed transport on the Bapaume road, the second squadron finding the road empty. After midday, Georges requested a maximum effort but only one more raid was flown, by two squadrons from 6:30 p.m., around Albert and Doullens. During the night, Bomber Command and the AASF flew 130 sorties and lost five bombers.[7]

BEF

During the winter of 1939–1940, BEF brigades had been detached for a period in the Maginot Line, to gain experience of conditions close to German troops. Saar Force was composed of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (Major-General Victor Fortune) and attached mechanised cavalry regiment, machine-gun battalions, artillery, French troops and a composite RAF squadron of fighters and army co-operation aircraft. From 30 April to 6 May, the force took over a line on the Saar from Colmen to Launstroff, between the French 42nd and 2nd divisions. In early May, German patrolling and skirmishing died down but on the night of 9/10 May many German aircraft flew overhead. On 13 May, the divisional front was bombarded and German infantry attacks were repulsed. More attacks followed on the Franco-British positions and on 15 May, the division was ordered back to the ligne de reçeuil, before being relieved by the night of 22/23 May to concentrate at Étain, 25 mi (40 km) west of Metz.[8]

Soon after the end of Operation Dynamo, the Dunkirk evacuation, 100,000 British fighting and lines-of-communications troops south of the Somme were reinforced, losses in the three AASF fighter and six bomber squadrons in France were replaced and another two fighter and four bomber squadrons were sent from England.[9] Advanced parties of the 1st Armoured Division (Major-General Roger Evans) arrived at Le Havre on 15 May and moved to Arras. The German advance made operations in the area impossible and Luftwaffe bombing and mining of Le Havre made the port unsuitable for more landings. On 19 May, the War Office agreed that the rest of the division should land at Cherbourg and then concentrate at Pacy-sur-Eure, about 35 mi (56 km) south of Rouen. The rest of the division began to disembark on 19 May but had no artillery, was short of an armoured regiment and the infantry of the Support Group, which had been diverted to Calais. The division lacked wireless equipment, spare parts, bridging material and there were no tanks in reserve for the 114 light tanks and 143 cruisers in the armoured brigades.[10]

On 21 May, Evans was ordered to capture crossings over the Somme from Picquigny to Pont-Remy and then be ready to operate to the east or north depending on circumstances. The area south of the lower Somme was the Northern District of the BEF supply system (Acting Brigadier Archibald Beauman) with sub-areas at Dieppe and Rouen. Beauman had received intelligence that the Germans had already captured the Somme crossings and were moving on the Seine bridges near Rouen. Beauman ordered the crossings to be secured by part of the divisional Support Group and next day part of the division concentrated in the Forêt de Lyons, east of Rouen as a flank guard on the lower Andelle and to protect the arrival of the rest of the division, due on 23 May. Early that day, part of the 1st Armoured Division advanced to the Bresle on a line from Aumale to Blangy, as reports were received that the German forces on the southern flank were on the defensive, only reconnoitring south of the river as they attacked St Omer and Arras in the north. The French Seventh Army had closed up to German positions from Péronne to Amiens, ready to cross the river on 23 May. GHQ ordered an attack by the 1st Armoured Division, to combine with the Anglo-French operations at the Battle of Arras which had begun on 21 May.[10]

Lines of communication

On the night of 22/23 May, Allied forces north of the Somme were cut off by the German advance to St Omer and Boulogne, which isolated the BEF from its supply entrepôts in Brittany, at Cherbourg in Normandy and at Nantes. Dieppe was the main medical base of the BEF and Le Havre the principal supply and ordnance source. From St Saëns to Buchy, north-east of Rouen, lay the BEF ammunition depot; infantry, machine-gun and base depots were at Rouen, Évreux and l'Épinay. A main railway line linking the bases and connecting them with bases further west in Normandy and with the BEF in the north, ran through Rouen, Abbeville and Amiens. Brigadier Beauman was responsible for base security and guarding 13 airfields under construction by troops drawn from the Royal Engineers, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Corps of Signals and older garrison troops.[11]

Further south, in the Southern District, were three Territorial divisions and the 4th Border Regiment, 4th Buffs and the 1st/5th Sherwood Foresters, lines-of-communication battalions, which were moved into the Northern District on 17 May as a precaution.[11] Rail movements between the bases and the Somme quickly became difficult, due to congestion and German bombing, the trains from the north mainly carrying Belgian and French troops and the roads filling with retreating troops and refugees. Beauman lost contact with GHQ and was unable to discover if Allied troops were going to dig in on the Somme or further south. On 18 May, Major-General Philip de Fonblanque, commanding the lines-of-communication troops, ordered Beauman to prepare defences in the Northern District. Beauforce was improvised from the 2nd/6th East Surrey of the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division, 4th Buffs, four machine-gun platoons and the 212th Army Troops Company RE.[12]

Vicforce (Colonel C. E. Vickary) took over five provisional battalions, created from reinforcement troops in BEF infantry and general base depots, which held plenty of men but few arms and little equipment.[12] Beauforce was sent by road to Boulogne on 20 May but the Germans had already cut off the port and it returned to the 12th Division near Abbeville. When German troops captured Amiens on 20 May and then began patrolling south of the river, their appearance caused panic and alarmist reports, in the absence of reliable information. Beauman ordered the digging of a defence line along the Andelle and Béthune rivers, which were the most effective tank obstacles south of the Bresle river, to protect Dieppe and Rouen from the east. Bridges were prepared for demolition and obstacles placed on their approaches.[12]

Prelude

German preparations

On 21 May, Panzergruppe von Kleist prepared the Somme bridges for demolition and outposts were pushed as far south as Moyenneville, Huppy, Caumont and Bailleul, where anti-tank guns had been dug in and camouflaged among the woods.[13] Later in the day orders arrived for the advance to resume northwards towards the Channel Ports but parts of the group were held back in reserve on 22 May, due to the Allied counter-attack at Arras on 21 May, until reinforced by the XIV Corps and the 2nd Motorised Division, which began to take over the defence of the Somme bridgeheads the next day. The staff of Engineer Regiment 511 (Colonel Müller) and Engineer battalions 41 and 466 were added to the 2nd Motorised Division, ready to blow the Somme bridges in an emergency as the division probed south to the Bresle, Aumale and Conty. When the XIV Corps arrived it was to continue to expand the bridgeheads on the south bank.[14]

Allied preparations

After a reform of the French command structure in January 1940, the Allied chain of command in the region around Abbeville was Général d'armée Maxime Weygand (Supreme Commander from 19 May), General Alphonse Joseph Georges (Commander North-Eastern Front [including the BEF]), General Besson (Groupe d'armées 3), General Aubert Frère (Seventh Army) General Robert Altmayer (Group A/Tenth Army) and General Marcel Ihler (IX Corps), in command of Evans and Fortune, with the BEF (Field Marshal Lord Gort) with a veto over French orders by appeal to the War Office (Secretary of State for War Oliver Stanley) and having vaguer responsibilities for the British forces south of the Somme.[15] In the afternoon of 18 May, Georges ordered the Sixth Army, Seventh Army and the 4e Division cuirassée (4e DCr, Colonel Charles de Gaulle) to organise the defence of the Crozat Canal line and the Somme, between Ham and Amiens. The Seventh Army was ordered to keep its forces ready for a counter-attack at the left flank of the attacking German forces. Troops withdrawing from Belgium were to organise a defence line further west, around Abbeville to the English Channel. From 19 May to 4 June the SNCF railways moved 32 infantry divisions to the area from the Aisne to the Somme, despite German air superiority and the bombing of railway lines and junctions.[16]

The 2nd Armoured Brigade (Brigadier F. Thornton) consisted of the HQ and the Queen's Bays, 9th Queen's Royal Lancers and the 10th Royal Hussars armoured regiments. The HQ and the Bays had landed at Cherbourg on 20 May and had deployed on the Bresle from Aumale to Blangy. The other two armoured regiments arrived on the night of the 22/23 May, crossed the Seine on 23 May to join the brigade, arriving at Hornoy and Aumont on the Aunoy–Picquigny road, having travelled 65 mi (105 km) since de-training. Thornton also had the 101st Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment (less Bofors guns) and three companies of the 4th Border from Beauforce from 24 May. An advanced party of the Bays from the 2nd Armoured Brigade moved forward, during the night to Araines, 4 mi (6.4 km) from the Somme at Longpré and lost two tanks on mines trying to capture the bridge, then found that all the bridges and the road along the south bank had been mined, blocked and guarded.[17]

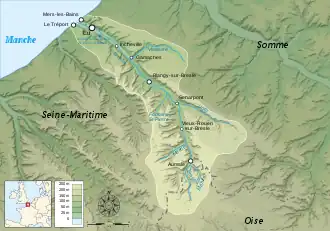

An attack was ordered on the bridges at Dreuil, Ailly and Picquigny, with a company of the 4th Borders and a troop of the Bays at each place. At Ailly, the Borders got two platoons across the river despite the bridge being blown but with the tanks stranded on the south bank the party was withdrawn. The groups at Ailly and Picquigny could not reach the river due to the strength of the German forces holding the bridgeheads, the Borders suffering many casualties and the Bays several tanks. The Borders spent the night at a wood 8 mi (13 km) south of Ferrières and the Bays between that village and Cavillon.[18] The 51st (Highland) Infantry Division arrived on the Channel Coast during the early Allied attacks on the German bridgeheads south of the Somme and assembled on the Bresle, after a difficult journey from the Saar due to German bombing, frequent changes of plan and delays caused by the big regrouping of the French armies south of the Somme. The divisional HQ was established at St Leger, 7 mi (11 km) south of Blangy on 28 May under the command of the French IX Corps.[19]

Plan

The ground north of the Bresle is a flat plateau cut with wooded river valleys draining into the Bresle or the Somme and is dotted with villages obscured behind trees, among open fields with little cover.[13] Under the impression that the Allied attack at Arras on 21 May was the beginning of operations either side of the panzer corridor, to trap the German armoured spearheads at the end of the Somme valley, BEF GHQ ordered the 1st Armoured Division to advance, with such units as were available, without delay. Unbeknownst to the Allies, the "mangled remains of six panzer divisions" supposedly between the BEF and the Somme, was a force of ten panzer divisions which, by 23 May, were reinforced by several motorised infantry divisions. The latter had arrived and dug in on the Somme crossings, south of Amiens and Abbeville. The Allied commanders judged it vital for the British 1st Armoured Division to cross the Somme on the left of the French Seventh Army. The division was to advance on St Pol to cut off German forces around St Omer, to relieve the right flank of the BEF. Evans thought that the British division, arriving piecemeal, with the support group and an armoured regiment diverted to Calais, with no artillery and with the French Seventh Army unprepared, could not achieve such an ambitious objective but he had to try.[17]

Georges passed orders to the Swayne Mission, the British liaison organisation at GQG, that the 1st Armoured Division was to mop up the Germans south of Abbeville, while the Seventh Army crossed the Somme. Gort, at BEF GHQ, replied that he wanted the division to attack, not pursue small German forces. General Robert Altmayer, the commander of Group B, the left flank units of the Seventh Army, sent other orders that the division must cover the left flank of the Seventh Army, during its attack on Amiens. The Swayne Mission then confirmed that the division was not under the command of Altmayer and was to carry out the existing orders. Evans ordered the 2nd Armoured Brigade, the only part of the division available, to close up to the Somme that night.[17]

During the night of 24/25 May, Evans was ordered by GHQ to co-operate with the French and wait in the existing positions. Georges had notified the Swayne Mission that the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division was moving from the Saar and would join the 1st Armoured Division to cover the ground from Longpré to the coast. On 24 May, Georges had informed Général d'Armée Antoine-Marie-Benoit Besson, the commander of Groupe d'armées 3, on the left flank of the Somme–Aisne line, that the 1st Armoured Division was to hold the line until the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division arrived, establish small bridgeheads and prepare the bridges for demolition. By this time the Germans were 5–6 mi (8.0–9.7 km) south of the river. GHQ also reported that the Germans were well dug-in and had strong patrols, supported by light armoured cars, between the bridgeheads and the Bresle. On 25 May Georges ordered (through the HQ of Groupe d'armées 3) that the German bridgeheads were to be destroyed. Evans was put under the command of the Seventh Army, with War Office agreement, which ordered a maximum effort. The War Office was unaware that the French were incapable of an attack from the south bank of the Somme sufficiently powerful to succeed or that while preparing for Fall Rot the Germans would reinforce the bridgeheads, two divisions having already dug in from Amiens to the sea, with more divisions moving into the area.[20]

On 26 May, orders for the attack were issued, the 2nd Armoured Brigade came under the 2e Division Légère de Cavalerie (2e DLC, Colonel Berniquet) to take high ground from Bray to Les Planches, which overlooks the Somme south-east of Abbeville, with support from French artillery and infantry. The 3rd Armoured Brigade was subordinated to the Division Légère de Cavalerie (5e DLC) for an attack on high ground from Rouvroy to St Valery-sur-Somme, also with French artillery and infantry in support. British tank commanders stressed to Général d'armée Besson, the commander of Groupe d'armées 3 and Frère the Seventh Army commander, that the British tanks were light tanks (Light Tank Mk VI) and cruiser tanks, similar to the equipment in French mechanised light divisions, not slow, heavily armoured infantry tanks like those in French armoured divisions.[21]

Battle

27 May

The Allied attack began at 6:00 a.m., after an hour's delay while the French artillery got ready. The 2e DLC and the attached British armoured brigade on the right flank, attacked from Hocquincourt, Frucourt and St Maxent, east of the Blangy–Abbeville road and the 5e DLC from the Bresle to north of Gamaches. Both of the DLCs had been depleted by earlier engagements and were unable to deploy any armour.[22] There had been little time to reconnoitre and information about German dispositions was sparse. To succeed, armoured attacks would need to be combined with artillery and infantry but there were far too few troops and guns; co-operation between the British and French was far from adequate. On the right flank, the tanks failed to advance far and many were knocked out at close-range by 37 mm Pak 36 anti-tank fire from Caumont and Huppy as they moved over ridges in between.[23][lower-alpha 2] On the left flank, the 3rd Armoured Brigade was able to reach high ground near Cambron and Saigneville and the edge of St Valery-sur-Somme on the coast. There was no infantry to follow up and consolidate the ground and the tanks were ordered to retire when the French were found to be digging in behind them at Behen, Quesnoy and Brutelles. The 1st Armoured Division suffered 65 tank losses, with some recovered and 55 breakdowns caused by lack of maintenance. Among the tanks put out of action were 51 Light Tanks Mk VI and 69 cruisers.[24] Minor repairs could be undertaken locally but more substantial work had to be done at the divisional workshops south-west of Rouen, where repairs were slowed by a lack of spares.[13]

28 May

.png.webp)

The French divisions on the Bresle attacked again, captured some German outposts and reached the Somme on both sides of the German bridgehead but failed to capture Abbeville and St Valery. The 1st Armoured Division recovered from its attack and reorganised, the 9th Lancers going into reserve and the remnants of the Bays and 10th Hussars being formed into a Composite Regiment of the 2nd Armoured Brigade. Georges sent Instruction 1809, reminding French commanders that the 1st Armoured Division was analogous to a French division légère mécanique (DLM, mechanised light division) and not suitable for attacks on prepared positions. It should be used with the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division on the left flank of IX Corps.[25][lower-alpha 3] The 4e DCr arrived, which although improvised, incomplete and having suffered many losses earlier in counter-attacks at the Battle of Montcornet (17 May), was much more powerful than the French cavalry divisions used hitherto and could field 137 tanks, 14 armoured cars (32 Char B1s, 65 Renault R35s, 20 SOMUA S35s, 20 Hotchkiss H35 modèle 39s and 14 Panhard 178s).[25]

The 4e DCr attacked on 28 May, either side of the Blangy–Abbeville road but was held up by the anti-tank defences in woods and a ridge running north-west from Villers sur Mareuil. The German front line was held by two battalions of Infanterie Regiment 217 reinforced by two companies of the Motorisierte Panzerabwehrabteilung 157 with an establishment of forty-eight 37 mm Pak 36.[27] The 4e DCr lacked heavy artillery and infantry for consolidation, having only four battalions of motorised infantry and about seventy-two 75 mm and 105 mm guns, which could inflict little damage on prepared positions. The French attack was preceded by an artillery bombardment, about 6,000 105 mm shells being fired on Huppy, about 83 rounds per gun. At 5:00 p.m., two battalions of Char B1s advanced towards the German positions and destroyed most of the machine-gun nests.[28] The German infantry of the 10th Company, IR 217 ran when they saw that the 37 mm Pak 36 had little effect on the French heavy tanks, claiming to have been attacked by French bombers and Char 2C Riesenpanzer (giant tanks). When the Char B1s continued their advance towards the Abbeville bridges, French infantry failed to keep up; indecision led the French tank crews to retire at dusk to their jumping-off positions and regroup.[29]

Eighteen Char B1s had been put out of action, three of which were repaired during the night. The German 9th Company, in reserve, was ordered to counter-attack immediately on the west flank of the French penetration, to close the gap and destroy the French forces which had broken through. While the company was concentrating near Caumont, it was surprised by the arrival of a new wave of French tanks of the 44e BBC, a R35 tank battalion.[29] The company engaged the tanks with four Pak 36 anti-tank guns but one was destroyed by 37 mm shells from a R35, another was smashed by a tank and the crews of the other two were killed by machine-gun fire from the tanks. The German company was overrun but the French infantry failed to keep up and the tanks retreated during the night.[30] The 3e Cuirassiers, a cavalry unit was attached to the 4e DCr and at about 6:00 p.m. attacked the eastern flank of the bridgehead with its Hotchkiss tanks, joined by the SOMUA S35s around 7:00 p.m. The tanks had great difficulty overcoming French barricades at Bellevue and were harassed by accurate German 105 mm howitzer fire, which could crack the deck armour with direct hits. At about 9:15 p.m., the tanks retired, having lost ten SOMUA S35s knocked out and thirteen Hotchkiss tanks which had broken down, suffered suspension damage or ditched.[31]

By the time that most of the French armour had withdrawn, the French infantry had advanced about 2.8 mi (4.5 km) into the bridgehead, more than half the distance to the bridges and taken about two hundred prisoners. The German III Battalion on the eastern flank had been routed, spreading panic in the Caubert area with tales of French Ungeheuer (monsters) and Stahlfestungen (steel fortresses). It was estimated that only about 75 men still had sufficient morale to defend themselves and the bridgehead collapsed, as the western flank had to be withdrawn to avoid it being encircled, reducing the area held by the Germans to about a sixth of its original extent. Whilst German artillery-fire was suspended due to uncertainty about the location of French positions, De Gaulle was also ignorant of the extent of the French advance and the vulnerability of the Germans. He ordered the tank units to rest and regroup during the night, ready to renew the advance at first light (4:00 a.m.) The respite allowed German command to recover and organise a new defensive perimeter.[32]

29–31 May

On 29 May, the 4e DCr attacked again, with parts of the 2e DLC and 5e DLC, while the British largely remained in reserve.[27] Due to the losses on the previous day, far fewer tanks were available. The French had 14 Char B1s, 20 R35s and about a dozen cavalry tanks. They were reinforced by the remaining tanks of the British 1st Armoured Division, attached to 5e DLC.[33] The tanks attacked the Mont de Caubert position, where German morale was still low. An important part of the German defence was Flak-Abteilung 64 which fielded about sixteen 88 mm guns, the armour-piercing ammunition of which could easily penetrate the Char B1 frontal armour. As the 37 mm anti-tank guns had been found to be ineffective, they were supplemented by 105 mm howitzers.[34] In the early morning, the Char B1s cleared the lower western and southern slopes of Mont de Caubert, against little resistance from the German infantry and destroyed a 105 mm howitzer position for the loss of one tank.[35]

When trying to take the summit of Mont de Caubert, a flat area lacking any cover, they discovered it was defended by a number of 105 mm and 88 mm guns, which had a clear field of fire. The Char B1s attacked several times and used most of their ammunition for a loss of two tanks, after which they withdrew to the slopes to replenish later in the morning. The R35 battalion started to advance around 9:00 p.m. and after clearing the area to the south-east of Caubert, reached the summit around noon and was immediately engaged by an outlying 88 mm gun. Surprised by what they mistook for a 94 mm gun, the French directed the fire of 75 mm field guns which destroyed the 88 mm.[36] The flanks of the bridgehead had crumbled as the 3e Cuirassiers advanced in the east and the 5e DLC moved from the west, which routed the German troops in this sector. When the 37 mm Pak 36 crews of the 5th Company saw the British tanks, they immediately withdrew, followed by much of the infantry. The retreat caused a panic among the supply and transport troops in the pocket, who fled over the Somme bridge into Abbeville.[37]

To stop the rout, the German commanders ordered the 5th Company and other unreliable units out of the bridgehead, so that troops holding firm, such as the 2nd and 6th companies, would not be affected. Generalleutnant Erich von Manstein, the XXXVIII Corps commander, was warned and rallied the personnel in Abbeville. Generaloberst Günther von Kluge, the 4th Army commander, informed by Manstein that a "rather serious crisis" had developed, consented to an evacuation of the pocket, should this become unavoidable. The 2nd Motorised Infantry Division at Rue was alerted and sent out advance parties to reconnoitre. The orderly withdrawals over the bridge were seen by the French and at noon, De Gaulle issued an order announcing the German abandonment of the bridgehead and that the 4e DCr should immediately exploit this by advancing towards the river.[38]

The French advance came to a halt and at 2:00 p.m., the Char B1 battalions asked for an artillery bombardment of the German defences on Mont de Caubert, to destroy the 88 mm guns but this did not begin until 8:00 p.m. Allied attacks at the west flank of the pocket at Cambron were stopped by close-range fire from 105 mm howitzers. The R35 battalion did not advance and the German commanders sent the rallied troops back over the river to raise their morale by conducting counter-attacks.[39] The German advance southwards from Mont de Caubert was repulsed by 75 mm-fire from the Char B1s but the tanks were forced to expose themselves to the German guns and lost another four vehicles; by late afternoon only seven Char B1s were operational. German counter-attacks around Cambron became so threatening, despite the deployment of a battalion of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, that French cavalry tanks were moved from the east to the west side of the bridgehead to repulse them; a lull fell in the evening.[40]

The failure of the French, completely to reduce the bridgehead, was caused by the German defenders, fatigue of the troops, tank losses and a false impression given in the order by De Gaulle, that the battle had already been won.[41] The French had overrun about half of the bridgehead, inflicted severe casualties on German officers and NCOs, taken about 200 prisoners and routed more than two infantry battalions of the 57th Infantry Division (Lieutenant-General Oskar Blümm). After three hours, the German infantry had rallied and reoccupied their positions unopposed; the offensive ended on 30 May, the French having lost 105 tanks in three days.[42][43]

1–3 June

Weygand abandoned the northwards counter-offensive over the Somme and Aisne rivers by 1 June but wanted the attacks on German bridgeheads south of the Somme to continue, as a defensive measure against the expected German offensive against Paris. Georges ordered a pause in the attacks by the Seventh Army, to regroup ready for an attack on 4 June. Groupe A became the Tenth Army, which included the 1st Armoured and 51st (Highland) Infantry divisions, in IX Corps, in which the 4e DCr was replaced by the 31st (Alpine) Division and the 2e Division cuirassée (2e DCr). The troops under Beauman were organised as the Beauman Division, with three improvised infantry brigades, an anti-tank regiment, a field artillery battery and service troops. Karslake was informed by the government that ad hoc forces should go back to England, with only enough lines-of-communication troops retained to support an armoured division, four infantry divisions and the AASF; Georges persuaded the War Office to keep the Beauman Division on the Andelle–Béthune line.[44]

From 1 to 3 June, the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (still over-strength because of the attachments for Saarforce), the Composite Regiment and the remaining elements of the 1st Support Group, relieved the two French divisions opposite the Abbeville–St Valery bridgehead, with the 153rd Infantry Brigade in reserve on the Bresle from Blangy to Senarpont; 9 mi (14 km) of the river on the right were held by a small force, with the Composite Regiment further back between Aumale and Forges; downstream, a pioneer battalion held a 16 mi (26 km) stretch. The Beauman Division held a 55 mi (89 km) line from Pont St Pierre, 11 mi (18 km) south-east of Rouen, to Dieppe on the coast, which left the British units holding an 18 mi (29 km) front, 44 mi (71 km) of the Bresle and 55 mi (89 km) of the Andelle–Béthune line, with the rest of the French IX Corps on the right flank.[45]

4 June

The Mont de Caubert spur runs northwards from the village of Mareuil-Caubert and there is a ridge west of Rouvroy which dominate the roads into Abbeville from the south. An Allied attack was planned for the 31st (Alpine) Division and the 2e DCr; on the right flank of the 2e DCr, the 152nd Infantry Brigade of the 51st (Highland) Division was to capture Caubert and woods from there to Bray. The 153rd Infantry Brigade on the left of the 31st (Alpine) Division, was to capture high ground south of Gouy and the 154th Infantry Brigade was to stand fast and engage German defenders around St Valery-sur-Somme by fire, to stop them being used to reinforce the Abbeville bridgehead; the Composite Regiment was to remain in reserve at St Léger. The French divisions came under the command of Fortune, having recently arrived and having had little time to prepare or reconnoitre. There were few photographs from air reconnaissance and the briefing of the troops was rushed, some parts of the 31st Division only arriving 90 minutes before zero hour. The German defences were mostly unknown and there were no aircraft to conduct artillery observation sorties, to direct the guns onto artillery emplacements and infantry forming-up areas.[46]

Zero hour was set for 3:00 a.m. and a mist filled the Somme valley, light enough for the attackers to assemble but not for this to be seen from afa. At 2:50 a.m. an Allied artillery bombardment fell on woods around Beinfay and Villers; the 2nd Seaforth advanced to capture German positions on the fringes of the woods, despite the French heavy tanks not arriving. The objectives were captured but by the time that the French tanks appeared, the barrage had stopped. As the tanks drove between the Blangy–Abbeville road and the woods they ran onto minefield, where they were engaged by German anti-tank guns and artillery. Several tanks triggered mines, blew up or caught fire and more were knocked out by the German guns but the rest reached the foot of Mont Caubert and Mesnil Trois Foetus. The 4th Seaforth were due to follow up supported by light tanks and when three arrived, they advanced on the south-east side of the woods near Villers, where they were received by massed machine-gun fire from Mont de Caubert and repulsed. When the heavy tanks were ordered back to the start line, only six of the 30 heavy tanks and 60 of the 120 light tanks returned.[47]

The attack of the 4th Camerons south of Caubert failed against well dug-in German machine-guns, although some troops advanced far enough to fight hand-to-hand. Two platoons got into Caubert and were cut off, the 152nd Brigade losing 563 men in its attack.[lower-alpha 4] On the left, an attack by a regiment of the 31st (Alpine) Division was quickly stopped by German troops dug in among woods to the west of Mesnil Trois Foetus but the attack of the 153rd Infantry Brigade on the left flank had more success. The 1st Black Watch attacked from the Cahon valley and reached Petit Bois and the 1st Gordon attacked from Gouy, pushed the Germans out of Grand Bois and reached their objective on high ground to the east at noon. The 1st Gordon was assisted by a system of Very light signals worked out with the artillery, which enabled them to direct the artillery onto German machine-gun nests. With the Germans still on the high ground north-west of Caubert, the area was untenable and the 1st Gordon were ordered back to their start line.[49]

Aftermath

Analysis

Confusion over Franco-British command arrangements south of the Somme was to an extent sorted out on 25 May, when the 51st (Highland) Division was subordinated to Ihler, the IX Corps commander, part of Groupe A (Altmayer) of the Seventh Army (Frère) and the 1st Armoured Division to Groupe A, which then became the Tenth Army. Military Mission 17, led by Lieutenant-General James Marshall-Cornwall, joined the Tenth Army HQ to co-ordinate British operations with the French. The inadequacy of command arrangements was exposed by the unrealistic expectations of the French of the 1st Armoured Division, which was equipped with fast, lightly armoured, light and cruiser tanks, not the thickly armoured types in French armoured divisions. Altmayer still used the 2nd and 3rd Armoured brigades in the attack on 27 May, which cost the British 120 tanks for little gain in ground and which had to be given up for lack of infantry to consolidate.[50]

When the 4e DCr attacked from 28 to 30 May, the German 37 mm Pak 36 anti-tank guns shot away tank aerials and pennants but bounced off the armour. Some German troops panicked and ran away, 200 were captured and the French retook about half of the Abbeville bridgehead. The Allies had too few infantry to hold the captured ground and ended back on their start lines, minus 105 of the tanks of the 4e DCr. Allied attacks suffered from a chronic lack of tactical communication, caused by an inadequate number of radios. Tanks, infantry and artillery could not stay in contact or talk to their divisional headquarters and inter-army tactical liaison was only possible at the lowest level. On 4 June, French tanks drove onto a minefield in an area thought to be held by the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division. The Highlanders had been withdrawn during the evening of 3 June and had failed to notify the French troops on the flanks; German troops followed up and planted the mines in an obvious tank avenue between woods.[51]

In 1953, the British official historian, Lionel Ellis, wrote that the Allied attacks on the Abbeville bridgehead lacked co-ordination, which contributed to the Allied failures to overcome German defences and magnified the effects of lack of preparation, the persistent underestimation of the strength of the German positions south of the Somme. The Allies were in ignorance of the assembly of Army Group B on the north bank of the Somme, the German formation preparing for Fall Rot, which was due to begin on 5 June, against Allied positions from Caumont to Sallenelle on the coast, south of St Valery.[52] In 2001, Caddick-Adams wrote that when the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division arrived from the Saar and relieved parts of the 4e DCr, 2e DLM and 5e DLM, it had a front of 24 mi (39 km) to hold. When Fall Rot began on 5 June, the Tenth Army units opposite the German bridgeheads from Abbeville to the sea were pushed back 15 mi (24 km) to the Bresle and further back on 8 June. Defeatism spreading through the French army was reflected in the Tenth Army HQ, which ceased to operate from 8 to 10 June.[51]

Robert Forczyk, in his 2017 book "Case Red: The Collapse of France", called the Battle of Abbeville an Allied fiasco. The German bridgeheads has not been destroyed and a British and two French armoured divisions had been depleted by the loss of 200 tanks and 2,000 infantry, in which state they were incapable of forming a mobile reserve to defend the Weygand Line. The German were able to use the bridgeheads as springboards despite their reduced size.[53]

Casualties

On 27 May, the attacks of the 1st Armoured Division, 2e DLC and the 5e DLC cost the British 51 Light tanks Mk VI knocked out and another 65 cruiser tanks out of 180 tanks engaged, about half of the losses from German fire and the rest from mechanical breakdowns. German casualties amounted to forty men killed and 110 wounded or missing.[54] From 29 to 30 May the 4e DCr lost 105 tanks but managed to inflict a measure of "tank panic" on some German troops. When they realised that the French tanks were impervious to their 37 mm anti-tank guns the Germans tried to retreat; outside Huppy 25 troops surrendered to the French. On the right flank of the attack, much of III Battalion IR 217 was lost with 59 men killed and 200 taken prisoner. in two days the Germans lost twenty anti-tank guns. By the morning of 30 May the 4e DCR had been reduced to about forty R35 and H39 light tanks, 100 tanks having been lost along with 626 infantry casualties, 104 men being killed. The German 57th Infantry Division suffered about 1,000 casualties; all the 37 mm anti-tank guns in the bridgehead had been destroyed. The German casualties included about 300 prisoners.[55] On 4 June the Franco-British force suffered about 1,000 infantry casualties; fifty tank and other armoured vehicles were also lost.[51] In 2017 Robert Forczyk wrote that the Allied attacks at Abbeville cost them 200 tanks and 2,000 infantry.[53]

5 June

On 5 June, Fall Rot (Case Red), a German offensive to complete the defeat of France began and Army Group A (Colonel General Gerd von Rundstedt) attacked either side of Paris towards the Seine.[56] The 4th Army offensive on the Somme began at 4:00 a.m. opposite the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division at St Valery-sur-Somme. German infantry moved forward against Saigneville, Mons, Catigny, Pendé, Tilloy and Sallenelle, held by the 7th and 8th battalions, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Argylls), as other troops passed between them, the villages being too far apart for mutual support. Saigneville, Mons, Catigny, Pendé and Tilloy fell late in the afternoon and the 7th Argylls were surrounded at Franleu by troops infiltrating between Mons and Arrest, as they were attacked frontally. The 4th Black Watch were ordered from reserve to relieve Franleu but were stopped by German troops at Feuquières and an Argylls company sent forward was surrounded at the edge of Franleu. By dark, the remnants of the 154th Infantry Brigade had been pushed back to a line from Woincourt to Eu.[57][lower-alpha 5]

On the right, the 153rd Infantry Brigade was bombarded by Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers as well as by mortar and artillery fire. The German infantry pushed the battalion back to Tœufles, Zoteux and Frières, where British machine-gun and artillery fire stopped the advance. The 31st (Alpine) Division was forced back parallel to the British from Limeux to Limercourt and Béhen, with the 152nd Infantry Brigade on the right retreating from Oisemont to the Blangy–Abbeville road. At Bray, to the east, the 1st Lothians were forced back to the east of Oisement. The Composite Regiment had several engagements and had some tank casualties before rallying at Beauchamps on the Bresle. The 51st (Highland) and 31st (Alpine) divisions had tried to hold a 40 mi (64 km) front and were so depleted after the bridgehead attacks up to 4 June, that the 1st Black Watch had been required to hold a 2.5 mi (4.0 km) front, in close country.[58]

See also

Notes

- The 25th Infantry Brigade discovered that it had lost 1,166 of 2,400 men, when the remnants rallied at Rouen on 23 May. The 2/5th Queens had 178 survivors, the 2/6th was intact except for one platoon and the 2/7th had 356 men left.[3]

- Corporal Hubert Brinkforth, disabled eleven light tanks in the course of twenty minutes, for which feat he later received the Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes.[23]

- Once equipped with Somua S35s, "light" became misleading in the title division légère mécanique (mechanised light division) but DLM was retained to distinguish this type of unit from DM (Divisions Marocaine) and DIM (divisions motorisées, motorised infantry divisions).[26]

- The surrounded platoons broke out two days later and reached Allied lines at Martainneville.[48]

- The 7th Argylls commander sent out most of the wounded and others by lorry that evening and the rest were overwhelmed later. The Argylls company held on for 24 hours before being overrun.[57]

Footnotes

- MacDonald 1986, p. 8.

- Karslake 1979, pp. 70–71.

- Karslake 1979, p. 71.

- Frieser 2005, p. 274.

- Karslake 1979, p. 67.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 80–81, 85.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 81–83.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 251–252.

- Sebag-Montefiore 2006, p. 458.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 254–255.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 252–253.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 253–254.

- Ellis 2004, p. 260.

- Guderian 1974, pp. 499, 113–114, 502–504.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 262, 11–12.

- Chapman 2011, p. 351.

- Ellis 2004, p. 256.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 256–257.

- Ellis 2004, p. 262.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 257–258.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 259–260.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 108.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 110.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 113.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 118.

- Jackson 2003, p. 257.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 119.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 124.

- Buffetaut 1996, pp. 129–130.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 132.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 133.

- Buffetaut 1996, pp. 133–134.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 136.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 137.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 139.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 140.

- Buffetaut 1996, pp. 141–142.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 142.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 144.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 145.

- Buffetaut 1996, p. 146.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 261–262.

- Caddick-Adams 2001, p. 47.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 264–265.

- Ellis 2004, p. 265.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 265–266.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 266–267.

- Ellis 2004, p. 267.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 267–268.

- Caddick-Adams 2001, p. 46.

- Caddick-Adams 2001, pp. 47–48.

- Ellis 2004, p. 268.

- Forczyk 2019, p. 263.

- Forczyk 2019, p. 250.

- Forczyk 2019, pp. 254–259.

- Cooper 1978, pp. 237–238.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 271–272.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 272–273.

References

- Bond, B.; Taylor, M. D., eds. (2001). The Battle for France & Flanders Sixty Years On. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-811-4.

- Caddick-Adams, P. "Anglo-French Co-operation during the Battle of France". In Bond & Taylor (2001).

- Buffetaut, Yves (1996). "Le Mois Terrible: La Bataille d'Abbeville" [The Dreadful Month: The Battle of Abbeville]. Armes Militaria Magazine, Collection Hors-série 21. Les Grandes Batailles de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale (in French) (II): 84–162. OCLC 41612528.

- Chapman, Guy (2011) [1968]. Why France Collapsed (Bloomsbury Reader ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-4482-0513-4.

- Cooper, M. (1978). The German Army 1933–1945, its Political and Military Failure. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-2468-1.

- Ellis, Major L. F. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1953]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-056-6. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Forczyk, R. (2019) [2017]. Case Red: The Collapse of France (pbk. Osprey ed.). Oxford: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4728-2446-2.

- Frieser, K-H. (2005). The Blitzkrieg Legend (English trans. ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-8128-2468-1.

- Guderian, Heinz (1974) [1952]. Panzer Leader (Futura ed.). London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0-86007-088-7.

- Jackson, J. (2003). The Fall and France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940 (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280300-X.

- Karslake, B. (1979). 1940 The Last Act: The Story of the British Forces in France after Dunkirk. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-240-2.

- MacDonald, John (1986). Great Battles of World War II. Toronto, Canada: Strathearn Books. ISBN 978-0-86288-116-0.

- Sebag-Montefiore, H. (2006). Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-102437-0.

Further reading

- Bond, Brian (1990). Britain, France and Belgium 1939–1940 (2nd ed.). London: Brassey's. ISBN 978-0-08-037700-1.

- Corum, James (1997). The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918–1940. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0836-2 – via Archive Foundation.

- Glover, Michael (1985). The Fight for the Channel Ports, Calais to Brest 1940: A Study in Confusion. London: Leo Cooper and Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-18210-6.

- Harman, Nicholas (1980). Dunkirk: The Necessary Myth. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-24299-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Horne, A. (1982) [1969]. To Lose a Battle: France 1940 (repr. Penguin ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-14-005042-4.

- Maginniss, Clem (2021). A Great Feat of Improvisation: Logistics and the British Expeditionary Force in France 1939–1940. Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-913336-15-8.

- Marix Evans, Martin (2000). The Fall of France: Act with Daring. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-969-0.

- Marot, Jean (1967). Abbeville 1940: Avec la division cuirassée De Gaulle [Abbeville 1940: With the Armoured Division De Gaulle] (in French). Paris: G. Durassié et Cie. OCLC 600777821.

- Montfort, M. (1964). "La bataille de la tête de pont d'Abbeville du 28 au 31 mai 1940: étude comparée" [The Battle of the Abbeville Bridgehead from 28 to 31 May 1940: Comparative Study]. Revue Militaire Suisse (Imprimeries Réunies S.A.) (in French) (online, ETH-Bibliothek ed.) (109). doi:10.5169/seals-343180. ISSN 0035-368X.

- Taylor, A. J. P.; Mayer, S. L., eds. (1974). A History Of World War Two. London: Octopus Books. ISBN 978-0-7064-0399-2 – via Archive Foundation.

- The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (Public Record Office War Histories ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Air Ministry. 2001 [1948]. ISBN 978-1-903365-30-4. AIR 41/10.

- Wailly, H. de (2012). L'offensive blindée alliée d'Abbeville: 27 mai – 4 juin 1940. Campagnes & stratégies (in French) (paperback ed.). Paris: Economica. ISBN 978-2-7178-6477-9.

- Wailly, H. de (1990). De Gaulle sous le casque. Abbeville 1940. Présence de l'histoire. Paris: Librairie académique Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-00763-8.