Peruvian political crisis (2017–present)

Since 2016, Peru has been plagued with political instability and a growing crisis, initially between the President, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Congress, led de facto by Keiko Fujimori.[13][14][15][16][17] The crisis emerged in late 2016 and early 2017 as the polarization of Peruvian politics increased, as well as a growing schism between the executive and legislative branches of government.[18] Fujimori and her Fujimorist supporters would use their control of Congress to obstruct the executive branch of successive governments,[19][20] resulting with a period of political instability in Peru.[13]

| Peruvian political crisis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 2016 – present | ||||

| Location | |||||

| Caused by |

| ||||

| Status | Ongoing

| ||||

| Parties | |||||

| |||||

| Lead figures | |||||

| Peruvian political crisis |

|---|

|

| Causes |

| Events |

|

| Elections |

| Protests |

| Armed violence |

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

| History of Peru |

|---|

|

|

|

Afflicted by corruption, Congress launched an attempt to remove President Kuczynski from power in December 2017, which failed. Following the emergence of a vote buying scandal related to the pardon of Alberto Fujimori in March 2018, Kuczynski resigned under pressure of impeachment. Kuczynski's successor Martín Vizcarra similarly had tense relations with Congress. During Vizcarra's efforts to combat corruption, he dissolved Congress and decreed snap elections in January 2020, which led to Popular Force losing its majority in Congress. Following corruptions scandals and an impeachment attempt in September 2020, Vizcarra was successfully removed and replaced by Manuel Merino on 9 November 2020, which sparked unrest. After five days in office, Merino resigned. His successor, Francisco Sagasti, briefly stabilized the country while having tense relations with Congress.

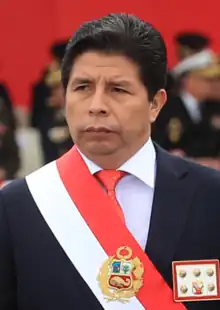

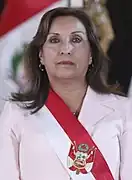

During the 2021 Peruvian general election, a crisis emerged between Fujimori and presidential candidate Pedro Castillo, who eventually went on to win the election. Following an electoral crisis, Castillo was inaugurated amid tensions with Fujimori and her allies, as well as the traditional political elite. Castillo faced harsh criticism from a far-right Congress and removal attempts.[21][22] Following a failed second removal attempt, protests broke out against Castillo. Castillo remained highly unpopular throughout his presidency. Following initiations of a third removal attempt, Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress. Castillo was later removed from office and was replaced by his vice president, Dina Boluarte. Boluarte, who initially was elected with Castillo's campaign, began to side with the political elite as protests against Castillo's removal broke out. Governmental response to the protests was criticized following massacres in Ayacucho and Juliaca, as well other reports of human rights abuses.[23] Through packing the Constitutional Court of Peru with supporters, Fujimorists consolidated power within Congress, gaining control of high institutions in the country.[24][25][26][27][28]

Since the crisis began, Peru has been plagued with democratic backsliding,[29] authoritarianism,[30][31] an economic recession,[32] and endemic corruption,[33] as well as impunity.[34] Three of Peru's presidents have been described as authoritarian since the crisis began,[31][35][36][37] while the majority of former presidents have been either imprisoned or subject to criminal investigations.[lower-alpha 1] The crisis also caused a loss of support for political parties and politicians in general,[38] which has led to Peru being labeled as a 'failed democracy'.[31][39][40][41]

Background

Following the collapse of the Fujimori regime in November 2000, his political legacy was followed by his daughter Keiko Fujimori, who led the Fujimorist Popular Force party. Fujimori and her party, as well as their right-wing allies in Congress, led an obstructionist campaign during the presidency of Ollanta Humala, who led a weak presidency as a result and was essentially powerless.[42][43][44]

The 2016 elections had some of the largest political blocs at the time, Popular Force led by Keiko Fujimori, Broad Front led by Verónika Mendoza and Peruvians for Change directed by Kuczynski. At first it was believed that both the Congress and the Presidency would be occupied by the members of Popular Force due to their overwhelming majority; the other two parties already mentioned occupied the third and second place respectively. Mendoza (who was in third place) decided to ask her voters to support the election of the Peruvians for Change party so that she could achieve power. The objective of the Broad Front was to counteract the large number of voters who had Popular Force. This objective was half-fulfilled, since Kuczynski came to the Presidency by a narrow margin,[45] while Popular Force managed to maintain hegemony in Congress.[46]

In the Constitution of Peru, Article 113 allows for the removal of the President of Peru for "moral capacity", with the measure existing since the 1839 Constitution of Peru.[47] Until 2004, there was not a concrete procedure to enact the vacancy of a president, with the Constitutional Court of Peru recommending a clarified process.[48] Due to broadly interpreted impeachment wording in the constitution, the Congress can impeach the President of Peru without cause, effectively making the legislature more powerful than the executive branch.[25][49]

Timeline

Kuczynski presidency

Following the 2016 election of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski to the presidency, tensions between the PPK-led executive branch and the opposition-led congress, dominated by Fujimorists from the Popular Force, rose. Corruption scandals plagued the government for the first year, as well as the Odebrecht scandal, national protests and strikes, and cabinet resignations.

Executive-Congress conflict begins

On 17 August 2017, members of Congress belonging to Popular Force filed a motion of interpellation against the Minister of Education Marilú Martens who was in negotiations with the representatives of the teachers, in search of the solution to a prolonged teacher strike.[50] On 25 August, the plenary session of the Congress approved the motion of interpellation, with 79 votes in favor, 12 against and 6 abstentions. The votes in favor were from the bench of Popular Force, APRA, Broad Front and Popular Action. The date of the interpellation was set as 8 September. Martens answered a list of 40 questions, mainly about the teachers' strike that still persisted.[51] Martens acknowledged deficiencies in facing the teachers' strike, but assured that her management would not reverse the recognition of meritocracy within the teaching profession. On 13 September, the Popular Force congresspeople announced that they would submit a motion of censure against Martens, since they claimed that she had not responded satisfactorily to the questions of the interpellation.[52] Faced with this threat of censorship (which would be the second against a head of Education in less than a year), Prime Minister Fernando Zavala asked Congress a question of confidence for the full ministerial cabinet.[53] Zavala's request was criticized by Congress, stating that Zavala was in solidarity with a minister who was questioned, endangering her entire cabinet, and even more, when the motion of censure had not yet been made official. It was also said that the "renewal of trust" was something that the Constitution did not contemplate.[54] In any case, the Board of Spokespersons of the Congress summoned Zavala on 14 September to support her request for confidence. Zavala presented himself to the plenary session of the Congress with the ministers and presented his request in 12 minutes; his argument focused on the government's intention to defend the education policy that was intended, according to him, to undermine the education minister's censure. Then they proceeded to the parliamentary debate.[53] The question of trust was debated for 7 hours and voted on 15 September. The cabinet failed to obtain the confidence of the Parliament, which voted against the confidence with 77, which produced the total crisis of the cabinet.[55]

On 17 September, Second Vice President Mercedes Aráoz was sworn in as president of the Council of Ministers of Peru and with this, five new ministers were announced: Claudia Cooper Fort (Economy), Idel Vexler (Education), Enrique Mendoza Ramírez (Justice and Human Rights), Fernando d'Alessio (Health) and Carlos Bruce (Housing). The new head of the cabinet was sworn in with the 18 ministers in a ceremony held in the Court of Honor of the Government Palace. On 6 October, the vote of confidence was given and if it were to fail, the president would have the right to dissolve Congress and call new elections, as the Constitution of 1993 said. The vote of confidence was delayed until 12 October, beginning with the exhibitions of the new cabinet led by Aráoz and subsequent intervention of the different political caucuses of the Congress until 0the next day. It resulted in 83 votes in favor and 17 against.[56]

Many political figureheads such as the media reported on the denial of confidence in the first cabinet; journalist Rosa María Palacios sent a message to the president asking him to dissolve the Congress[57] and warned that "Fujimorism has been trapped.[58] Journalist César Hildebrandt also sent a message to the president saying that "the country requires him to confront the Fujimorist Congress".[59] A former constitutional lawyer in an interview said that the former president of the Council of Ministers Fernando Zavala "is sacrificing for state policies",[60] the former president of the Council of Ministers Pedro Cateriano warned that "Keiko Fujimori, leader of the Popular Force party, wants to lead a coup d'etat".[61]

On 15 November, through Bill No. 2133, Congressman Mauricio Mulder presented the Mulder Law, which prohibited state advertising in private media and on 28 February 2018 approved the bill by the Permanent Commission of the Congress with 20 in favor, 3 against and 14 abstentions.[62][63] The ruling was approved at the urging of APRA and Fujimorism on 15 June 2018 with 70 votes in favor, 30 against and 7 abstentions.[64][65] and it was published on 18 June 2018 in the Legal Rules of the Official Gazette El Peruano.[66]

In November 2017, the Lava Jato Commission, a congressional commission chaired by Rosa Bartra investigating Odebrecht and its activities in Peru, as well as the concurrent scandal, received confidential information that President Kuczynski had had labor ties with this company, which went back to the time when he was both Prime Minister and the Minister of the Economy between 2004 and 2006, under the government of Alejandro Toledo, despite the fact that since the outbreak of the Odebrecht case, Kuczynski had denied him on several occasions.

The Commission then asked the Odebrecht company for details of its relationship with Kuczynski, which were publicly disclosed on 13 December. It was revealed then that Westfield Capital, an investment banking advisory firm, founded and directed by Kuczynski had carried out seven consultancies for Odebrecht between November 2004 and December 2007 for millions of dollars, that is, coinciding with the time when Kuczynski had been Minister of Economy (2004–2005) and Prime Minister (2005–2006). The information also revealed that another company closely related to Kuczynski, First Capital, formed by its Chilean partner Gerardo Sepúlveda, had also provided consulting services for Odebrecht between 2005 and 2013.[67]

First attempted impeachment

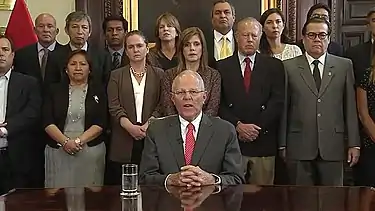

The opposition, led by Popular Force, demanded the resignation of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and threatened his impeachment if he did not do so. The Broad Front support holding an immediate impeachment vote. On 14 December, Kuczynski, through a message to the nation, denied the accusations and said he would not resign his position.

I am here to tell you: I am not going to abdicate my honor or my values or my responsibilities as president of all Peruvians,

— Pedro Pablo Kuczynski

In his defense, he claimed to have no relationship with the company First Capital, which was the sole property of Sepúlveda, and that only one of the payments mentioned had to do with him, the one dated in 2012, when he no longer held any ministerial positions. As for Westfield Capital, although he acknowledged that it was his sole proprietorship, he affirmed that he was never under his direction and administration while he was Prime Minister, and that the contracts dated at that time had been signed by Sepúlveda, his partner. He also noted that all payments to his company were legal, and that they were duly registered, billed and banked.[68] Kuczunski's explanations did not convince the opposition, and he was accused of continuing to lie, especially in relation to the fact that he had left Westfield Capital when he was minister, when, according to public records, he always figured as director of that company. Although PPK argued that there had been a "Chinese wall", an expression used in business to refer to when the partner or owner has no contact or receive information on the management of the company, while in public office (but in the case of Wesfield Capital, being a company where Kuczynski was its sole agent, it is unclear how this "Chinese wall" could be made). Faced with the refusal of the president to resign, several of the opposition caucuses of Congress then proposed to submit their position to the vacancy.

The Broad Front submitted a motion for the vacancy request to be debated in the plenary session of the Congress. The congresspersons of Popular Force, APRA and the Alliance for Progress joined the request and the motion surpassed more than the 26 signatures needed to proceed with the process. Once the motion was approved, the debate began on 15 December and lasted until later that day. The opposition legislators who introduced the motion cited a moral incapacity when they denounced that the president lied in the statements he gave about his ties with Odebrecht. The congresspeople demanded that the due process be followed, reproaching the fact that the opposition proceeded with unusual speed and that several of its members had already decided to empty the president without having heard his defense. They also questioned the fact that a single report from Odebrecht was considered sufficient evidence, thereby overtly dispensing with the investigation that demanded such a delicate and far-reaching case.

According to the regulations, the vote of 40% of competent congressmen was needed for the admission of the vacancy request. As 118 congressmen were present, only 48 votes were needed, which was widely exceeded, as they voted 93 in favor and 17 against; these last ones were, in their great majority, those of the pro-government caucus.[69]

Once the vacancy request was approved, the Congress agreed that on 21 December, Kuczynski should appear before the plenary session of the Congress to make his disclaimers; then it would proceed to debate and finally vote to decide the presidential vacancy, needed for this 87 votes of the total of 130 congressmen.[70]

On the appointed day, Kuczynski went to Congress to exercise his defense, accompanied by his lawyer Alberto Borea Odría. The defense began with the speech of the president himself, in which he denied having committed any act of corruption. Then came Borea's defense, which had as its axis the consideration that the vacancy request was an exaggeration because you could not accuse a president of the Republic without demonstrating with irrefutable evidence his "permanent moral incapacity", a concept that the congressmen did not they had apparently very clear, because strictly the constitutional precept would be referring to a mental incapacity. He considered that the offenses or imputed crimes had to be ventilated first in the investigating commission, before drawing hasty conclusions. He also rejected that PPK has repeatedly lied about his relationship with Odebrecht (argument that the Fujimoristas used to justify their permanent moral incapacity), because the facts in question had happened twelve years ago and he did not have to have them present in detail.[71]

After the speech of Borea, the congressional debate that lasted fourteen hours began. Voting for the vacancy took place after eleven o'clock at night, with the following result: 78 votes in favor, 19 against and 21 abstentions. One of the benches, New Peru, retired before the voting, because to say of its members they did not want to follow the game to Fujimorism. Since 87 votes were needed to proceed with the vacancy, this was dismissed.[72] The whole Popular Force bench voted in favor of the vacancy, with the exception of 10 of its members, led by Kenji Fujimori, who abstained, and who thus decided the result. The rumor spread that this dissident group, which would later be called the "Avengers", had negotiated its votes with the government in exchange for the presidential pardon in favor of Alberto Fujimori, its historical leader who was then imprisoned.[73] After the Popular Force bench and led by Kenji announced the formation of a new political group named Cambio 21, which would support the government.[74]

On 24 December 2017, Kuczynski granted a humanitarian pardon to Alberto Fujimori, who had been imprisoned for 12 years, with a sentence of 25 years for crimes of human rights violations committed during the Shining Path insurgency.[75] The government assured that the pardon had been decided for purely humanitarian reasons, in view of the various physical ills afflicting the former president of the Republic, confirmed by reports of a medical board.[76] However, a strong suspicion arose that the pardon would have been the result of a furtive pact of the Kuczynski government with the sector of the Fujimorist bloc that had abstained during the vote for the presidential vacancy and that had thus prevented it from concrete this. The pardon also motivated the resignation of the official congressmen Alberto de Belaunde, Vicente Zeballos and Gino Costa; of the Minister of Culture Salvador del Solar and Minister of Defense Jorge Nieto Montesinos. The Minister of the Interior, Carlos Basombrío Iglesias, had already resigned. There were also several marches in Lima and throughout the county of the country in protest of the pardon.

Alberto Fujimori, who days before the pardon had been admitted to a clinic for complications in his health, was discharged on 4 January 2018 and so could, for the first time, move freely.[77] President Kuczynski, meanwhile, formed a new ministerial cabinet, which he called "the Cabinet of Reconciliation," which according to him, should mark a new stage in the relationship between the Executive and the Legislative. Mercedes Aráoz held the post of Prime Minister, while eight ministerial changes were made, the most important renewal in what was going on in the government.[78]

Second impeachment and resignation

Only days after the first attempt at a presidential vacancy, in January 2018, the Broad Front caucus filed a new vacancy request, alleging Alberto Fujimori's pardon, which allegedly had been negotiated and granted illegally. This did not prosper, given the lack of support from Fuerza Popular, whose votes were necessary to carry out such an initiative. Under that experience, the leftist groups of Broad Front and Nuevo Peru promoted another vacancy motion, concentrating exclusively on the Odebrecht case, arguing that new indications of corruption and conflict of interest had been discovered by PPK when he was Minister of State in the government of Alejandro Toledo.[79] This time they won the support of Fuerza Popular, as well as other groups like Alianza para el Progreso (whose spokesperson, César Villanueva, was the main promoter of the initiative), thus gathering the 27 minimum votes necessary to present a multiparty motion before the Congress of the Republic, what was done on 8 March 2018.[80]

On 15 March, the admission of this motion was debated in the plenary session of the Congress, the result being 87 votes in favor, 15 votes against and 15 abstentions. The motion received the backing of all the benches, except for Peruvians for Change and non-grouped congressmen, among them, the three former pro-government officials and the Kenji Fujimori bloc.[81] The Board of Spokespersons scheduled the debate on the presidential vacancy request for 22 March. A confidential report from the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) on the money movements of Kuczynski's bank accounts was forwarded to the Public Ministry and the Lava Jato Commission of Congress, but inexplicably leaked to public knowledge. This 33-page document revealed that from the companies and consortiums linked Odebrecht transfers had been made to Westfield Capital, the one-person Kuczynski company, for millions. Transfers made to the account of the driver of Kuczynski and that of Gilbert Violeta were also revealed, although it was shown that these were only payments of a labor nature and of basic services.[82] The leak of this report, which is presumed to have been made by the Lava Jato Commission chaired by Rosa Bartra, would have been with the intention of further identifying the credibility of the President of the Republic.

On 20 March 2018, Popular Force showed evidence that the government was buying the support of congressmen to vote against the second presidential vacancy request, a rumor that had already circulated during the first process. It was a set of videos where the conversations made by the legislators Bienvenido Ramírez and Guillermo Bocángel (from the bench of Kenji Fujimori) to try to convince Congressman Moisés Mamani of Puno not to join to support the presidential vacancy, in exchange for works for his represented region. In one of the videos, Kenji Fujimori is seen in a meeting with Mamani, which also includes Bienvenido Ramírez. The latter makes a series of offers to the parliamentarian from Puno to enable him to streamline projects for his region, in exchange for joining his group and supporting Kuczynski. In another video we see Bocángel talking about the administrative control of the Congress, once they access the Board. And in a third video, we see Alberto Borea Odría, PPK's lawyer on the subject of vacancy, explaining to Mamani about aspects of that process and giving him the telephone number of a minister of state. Those involved in the scandal, came out to defend themselves, saying that it was normal practice for congressmen to turn to ministers to ask for works in favor of their regions. Congressman Bienvenido even said that he had only "bragged". But what was questioned was the fact that the government negotiated these works to reorient the vote of a group of congressmen on the issue of the presidential vacancy, which would constitute the criminal figure of influence peddling. A few hours later, Fujimorists gave the final thrust, by broadcasting a set of audios, in which the Minister of Transport and Communications, Bruno Giuffra is heard offering works to Mamani in exchange for his vote to avoid the vacancy. The press highlighted a phrase by Giuffra in which he says: "Comrade, you know what the nut is and what you are going to get out", presumably referring to the benefits Mamani would gain if he voted against the vacancy.[83] Until then, it was expected that the vote to achieve the vacancy would be very tight and that even Kuczynski could again succeed as had happened in the first process. But the Kenjivideos determined that several congressmen who until then had manifested their abstention (among them the three ex- oficialistas) folded in favor of the vacancy, and thus they made it known openly.[84]

Faced with the foreseeable scenario that awaited him in the debate scheduled for the Congress on the 22nd, PPK opted to renounce the Presidency of the Republic, sending the respective letter to Congress, and giving a televised message to the Nation, which was transmitted in the afternoon of 21 March.[85]

I think the best thing for the country is for me to renounce the Presidency of the Republic. I do not want to be a stumbling block for our nation to find the path of unity and harmony that is so badly needed and denied to me. I do not want the country or my family to continue suffering with the uncertainty of recent times (...) There will be a constitutionally ordered transition.

— Kuczynski, in his message of resignation to the Presidency of the Republic. Lima, 21 March 2018.

The Board of Spokespersons of the Congress, although rejected the terms of the letter of resignation of Kuczynski, arguing that this did not make any self-criticism and victimized, accepted the same and scheduled for 22 March a debate in Congress to evaluate the resignation. That debate lasted until the next day.[86] Although a section of congressmen on the left argued that the resignation of Kuczynski should not be accepted and that Congress should proceed to vacancy due to moral incapacity, the majority of congressmen considered that it should be accepted, to put an end to the crisis. When the preliminary text of the resolution of the Congress was published, in which it was indicated that the president had "betrayed the fatherland", Kuczynski announced that it would withdraw its letter of resignation if that qualification was maintained. The Board of Spokesmen decided then to omit that expression. The resignation was accepted with 105 votes in favor, 12 against and 3 abstentions.[87] Moments later, the first vice-president Martín Vizcarra was sworn in as the new constitutional president of the Republic.[88] Soon after, the new government announced that its prime minister would be César Villanueva, the main promoter for Kuczynski's vacancy.

Anti-corruption initiative

Following multiple corruption scandals facing the Peruvian government, on 28 July 2018, President Vizcarra called for a nationwide referendum to prohibit private funding for political campaigns, ban the reelection of lawmakers and to create a second legislative chamber.[89] The Washington Post stated that "Vizcarra's decisive response to a graft scandal engulfing the highest tiers of the judiciary ... has some Peruvians talking of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to restore integrity to public life and revive citizens’ waning faith in democracy".[90] Leftist lawmaker Marisa Glave, who was once a critic of Vizcarra, praised the move saying he had "connected with the people in a society that is both fed up with corruption but also deeply apolitical. It has put the Fujimoristas in check".[90] Transparency International also praised the move, stating that "This is a very important opportunity, one that is unlike previous opportunities because, in part, the president appears genuinely committed".[90]

On 3 October, the Judicial Branch issued placement and arrest warrants against former President Alberto Fujimori. His lawyers had 5 days (from 4 October) to support an appeal.[91] On 9 October, the appeal filed by his lawyers was rejected. Next, the judge ordered to locate him and capture him, an end of the sea re-entered in a prison.[92]

I want to tell the authorities and politicians today, because I no longer have the strength to resist it. (...) I want to ask the President of the Republic, the members of the Judiciary, only one thing: please do not kill me. If I go back to prison, my heart will not endure it, it is too weak to be able to go through the same. Do not condemn me to death, I do not give more "

— Alberto Fujimori, at the Centenario clinic, where he was interned, on 5 October 2018.[93]

As a result of the annulment of the pardon, the legislators at the end of Fujimorism, would approve a series of reforms.[94]

On 10 October, in the Office of the Prosecutor of Peru, Judge Richard Concepción Carhuancho ordered a preliminary detention of Keiko Fujimori for 10 days, for the alleged illicit contributions to the 2011 campaign from Odebrecht.[95][96]

The Office of the Prosecutor does not cite any evidence in the judicial decision. A person is given preliminary detention when there is a well-founded risk, or a well-founded suspicion, of a procedural danger. What is the danger if we are going to the Attorney's office voluntarily? What is the risk of flight?

— Defense of Keiko Fujimori at the time of the arrest.[97]

On 17 October, after an appeal, Fujimori was released, along with five other detainees, because no feasible evidences of her responsibility were found.[98]

On 15 November 2018, Alan García went to a meeting with the prosecution of money laundering, as part of an interrogation, carried out by, part of the prosecutor José Domingo Pérez due to irregularities in the conference payments of the former president, financed with money from Caja 2 of the structured operations division of the Odebrecht company, before this the prosecutor issued an order to prevent him from leaving the country for 18 months for García, even though at first he said he was at the disposition of the justice, that same night he went to the home of Carlos Alejandro Barros, ambassador of Uruguay, where he remained until 3 December 2018, when Uruguayan President Tabaré Vázquez, announced the rejection of Alan García's asylum request, consider that in Peru the three branches of the state functioned freely and without political persecution.[99][100]

On 9 December, Peruvians ultimately accepted three of four of the proposals in the referendum, only rejecting the final proposal of creating a bicameral congress when Vizcarra withdrew his support when the Fujimorista-led congress manipulated the proposals contents which would have removed power from the presidency.[101]

On 21 December, the government formalized the formation of the High Level Commission for Political Reform. It was made up of political scientist Fernando Tuesta Soldevilla, as coordinator, and academics Paula Valeria Muñoz Chirinos, Milagros Campos Ramos, Jessica Violeta Bensa Morales and Ricardo Martin Tanaka Dongo.[102] It was installed on 5 January 2019. Based on the report that said Commission gave, the government presented twelve proposals for political reform to Congress (11 April 2019). However, it excluded the issue of bicamerality, as it was recently rejected in the referendum.[103]

Among the three projects of constitutional reform was the one that sought the balance between the Executive and Legislative powers with the objective of establishing counterweights between both; the reform that modifies the impediments to be a candidate for any position of popular election, to improve the suitability of the applicants; and the reform that seeks to extend the regional and municipal mandate to five years, to coincide with the general elections. For the Legislative Branch, it was proposed that the election of the congressmen be carried out in the second presidential round; the elimination of the preferential vote and the establishment of parity and alternation in the list of candidates were proposed. On the other hand, for political parties, the aim was to promote internal democracy and citizen participation in the selection of candidates, establishing internal, open, simultaneous and compulsory elections organized by the ONPE. Other reforms related to the registration and cancellation in the registry of political organizations, and the requirements to keep the registration in force, as well as the regulation of the financing of political organizations, to avoid corruption. Another proposal was that the lifting of parliamentary immunity should not be the responsibility of Congress, but of the Supreme Court of Justice.[103]

On 23 January 2019 Alberto Fujimori was transferred again to the Barbadillo prison in the Ate District, where he was interned from 2007 to 2017, serving his sentence before being pardoned. The former president was discharged from the Centennial Clinic after a medical board of the Institute of Legal Medicine evaluated him and determined that he is stable and that he can receive treatment for his ailments.[104]

After a 3-day hearing, on 19 April, the Judiciary issued a sentence of 36 months of pre-trial detention for former President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski.[105] However, due to illness, on 27 April he was exchanged for house arrest.[106]

On 29 May, from the Great Hall of the Government Palace, President Vizcarra gave a message to the Nation, in which he announced his decision to raise the issue of trust before Congress in support of political reform. This, after the Constitution Commission, with a Fujimori majority, sent the bill on parliamentary immunity to the archive, and the Permanent Commission, also with a Fujimori majority, filed practically all the complaints weighing on the controversial prosecutor Chávarry. The president, accompanied by members of his ministerial cabinet and regional governors, stated that the issue of trust would be based on the approval, without violating its essence, of six of the bills for political reform, considered the most central:

- Changes in parliamentary immunity, so that it does not become impunity.

- Convicted persons may not be candidates.

- Any citizen must participate in the selection of candidates from political organizations, through internal primary elections.

- Eliminate the preferential vote and let the population define it in that previous selection.

- Guarantee the political participation of women with parity and alternation.

- Prohibit the use of dirty money from electoral campaigns.

If Congress denied the issue of confidence, it would be the second time that it did (the previous one went to the Zavala cabinet of the government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski), for which, according to the Constitution, faced with two refusals, the President would be empowered to dissolve Congress and call new parliamentary elections within four months.

The following day, Prime Minister Salvador del Solar appeared before Congress to deliver the official letter requesting that the time and date of the plenary session be established, in which he will support the issue of trust. In this document, Del Solar indicated that he would propose that the maximum term for the approval of the six political reforms be at the end of the current legislature (15 June); otherwise, it would consider that Congress denied confidence to the ministerial cabinet.[107] In response to the request, Congress President Daniel Salaverry called the plenary session for 4 June to meet the Executive's request for confidence.[108]

The six political reform projects were defined as follows:[109]

- Constitutional reform that states that those convicted in the first instance may not be candidates.

- Legislative reform on internal democracy, which seeks for citizens to participate in the selection of candidates from political organizations, through internal primary elections.

- Legislative reform that seeks to guarantee women's political participation, with parity and alternation, as well as eliminating preferential voting.

- Legislative reform on registration and cancellation of political parties and regional political organizations.

- Legislative reform that seeks to prohibit the use of illegal money in electoral campaigns.

- Constitutional reform to make changes in the process of lifting parliamentary immunity, so that it does not become impunity.

The Constitution Commission invited jurists Raúl Ferrero Costa, Natale Amprimo, Ernesto Álvarez, Aníbal Quiroga and Óscar Urviola to collect their opinions on the Executive's approach and the constitutionality of the approach.

On 4 June, Salvador del Solar appeared in the plenary session of Congress to expose and request the question of trust before the national representation. Previously, a previous question was rejected to evaluate the constitutionality of the trust request. Several voices in Congress considered that imposing a deadline for the approval of constitutional reforms and forcing their essence to be respected was unconstitutional, since reforms of this type were the exclusive responsibility of Congress and the Executive lacked the power to observe them. Due to these criticisms, Del Solar, in his presentation, lightened that part of his demand. He said that Congress was empowered to extend the legislature if necessary, and that it was not obliged to approve the bills to the letter, but could enrich them, although insisting that they should not alter their essence. "This question of trust is not a threat," he concluded.

After the presentation of the Prime Minister, the parliamentary debate began, which had to be extended until the following day. Finally, at noon on 5 June 2019, the vote was held. The question was approved with 77 votes in favor, 44 against and 3 abstentions. The members of the left-wing benches (Broad Front and New Peru) and the Aprista Party voted against, while those of Popular Force did so in a divided manner (33 in favor, 16 against and 2 abstentions).[110]

The Constitution commission debated the opinions between 7 June and 20 July. A series of changes were made in the projects, but the most striking was what was committed with the latest opinion, on the lifting of immunity of parliamentarians. The Constitution Commission rejected the Executive's proposal that the Supreme Court be in charge of raising immunity for congressmen, providing that Congress continue to retain that prerogative. The only variant was that it proposed definite terms for Congress to lift immunity once the Judicial Power made the respective request. In addition, it was proposed that the request be given only when there is a final judgment.[111]

When the Prime Minister Salvador del Solar was consulted on the opinions approved by the Constitution Commission, he considered that only five respected the spirit of the reforms proposed by the Executive, and that the last one, on parliamentary immunity, meant a setback, since it did not respect the a matter of trust, which had arisen precisely when the Constitution Commission sent the same project to the archive.[112]

The six projects were submitted to the plenary session of Congress, were approved between 22 and 25 July, including modifications that further accentuated the distortion of the original projects of the Executive, especially regarding internal democracy and parliamentary immunity.

Daniel Salaverry, elected president of Congress for the 2018–2019 legislature with the support of his Popular Force colleagues, starred in a series of confrontations with his colleagues, marked by a series of epithets, attempts at censorship and accusations, which led him to distance himself of Popular Force and approach President Vizcarra, who saw him as an ally to curb the dominance of Keiko Fujimori in Congress. This earned him retaliation from his former colleagues. An investigation of the television program Panorama denounced that Salaverry had repeatedly presented false data in his representation week reports (an obligation that congressmen have to visit the provinces they represent, to listen to the demands of their constituents), which included photos from other events.[113]

On 28 May 2020, Prime Minister Vicente Zeballos went to request the vote of confidence with his cabinet. He obtained 89 votes in favor, 35 against, and 4 abstentions.[114][115]

On 1 July, the Union for Peru bench presented a motion to interpellate Zeballos and the Minister of Justice, Fernando Castañeda, stating that urgent responses were required to the problems of public health, economic reactivation and corruption.45 As In response, the prime minister argued that although he respected the autonomy of Congress and both he and his ministers would continue to attend the summons issued by the different commissions, he considered that these motions (six in total, together with those previously presented against the heads of Economy, Health, Education and Development and Social Inclusion) did not add efforts to the fight against the coronavirus pandemic; but on the contrary, they sought to hinder the work of the Executive or to gain prominence.[116]

Dissolution of Congress

Demanding reforms in the Constitutional Court organic law, President Vizcarra called for a vote of no confidence on 27 September 2019, stating it was "clear the democracy of our nation is at risk".[117] Vizcarra and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights criticized Congress for blocking a proposal for general elections while it quickly approved nominations to the Constitutional Court of Peru without investigating the backgrounds on nominees.[117] Vizcarra sought to reform the Constitutional Court nomination process and Congress' approval or disapproval of his proposal was seen "as a sign of confidence in his administration".[117] The Congress scheduled the election of the new members to the Constitutional Court of Peru for 30 September. On 30 September, the prime minister Salvador del Solar went to the Legislative Palace to request the approval of an amendment to the Organic Law of the Constitutional Court as a matter of confidence. However, the Congress scheduled the minister to the afternoon. While the congress started the debate for the election of the new judges, the prime minister entered the Congress hemicycle room. Del Solar addressed the lawmakers to vote to reform the Constitutional Court nomination process. However, the Congress decided to postpone the vote of the amendment to the afternoon. The Congress named a new member to the Constitutional Court of Peru.[118] Many of the Constitutional Court nominees selected by Congress were alleged to be involved in corruption.[119] Hours later, the Congress approved the confidence motion. Notwithstanding the affirmative vote, Vizcarra stated that the appointment of a new member of the Constitutional Court constituted a de facto vote of no confidence.[118][120] He said that it was the second act of no-confidence in his government, granting him the authority to dissolve Congress.[121] These actions by Congress, as well as the months of slow progress towards anti-corruption reforms, pushed Vizcarra to dissolve the legislative body on 30 September, with Vizcarra stating "Peruvian people, we have done all we could."[118] Shortly after Vizcarra announced the dissolution of Congress, the legislative body refused to recognize the president's actions, declared Vizcarra as suspended from the presidency, and named Vice President Mercedes Aráoz as the interim president of Peru.[118] Despite this, Peruvian government officials stated that the actions by Congress were void as the body was officially closed at the time of their declarations.[118] By the night of 30 September, Peruvians gathered outside of the Legislative Palace of Peru to protest against Congress and demand the removal of legislators[118] while the heads of the Peruvian Armed Forces met with Vizcarra, announcing that they still recognized him as president of Peru and head of the armed forces.[122] During the evening of 1 October 2019, Mercedes Aráoz, whom Congress had declared interim president, resigned from office.[123] Aráoz resigned, hoping that the move would promote the new general elections proposed by Vizcarra and postponed by Congress.[123][118] President of Congress Pedro Olaechea was left momentarily speechless when informed of Aráoz's resignation during an interview.[124] At the time, no governmental institution or foreign government recognized Aráoz as president.[124] Vizcarra issued a decree calling for legislative elections on 26 January 2020.[123] The Organization of American States released a statement saying that the Constitutional Court could determine the legality of President Vizcarra's actions and supported his call for legislative elections, saying "It's a constructive step that elections have been called in accordance with constitutional timeframes and that the definitive decision falls to the Peruvian people".[124]

In the legislative elections that followed, Popular Force and their de facto coalition with the Aprista Party fell. APRA lost all of its seats for the first time in 25 years, while Popular Force lost 58 former seats, being left with 15. The successor party to Peruvians for Change, Contigo, also lost all of its seats.[125][126]

First impeachment

As Peru's economy declined due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru, President Vizcarra faced increased political pressure from the newly inaugurated congress presided by Manuel Merino, with the majority of the legislative body being controlled by those opposing Vizcarra.[127] Finally on 5 July 2020, Vizcarra proposed a referendum to be held during the 2021 Peruvian general election to remove parliamentary immunity,[128] though congress quickly responded by assembling that same night to pass their own immunity bill that contained proposals to remove immunity from the president, constitutional court and the human rights ombudsman while also strengthening some instances of parliamentary immunity.[129]

Since early 2020, investigations began surrounding a contract for a little-known singer by the name of Richard Cisneros to perform speeches for the Ministry of Culture.[127] It was alleged that an inexperienced Cisneros was able to receive payments totaling US$50,000 due to contacts in the Government Palace.[127] Investigators searched offices in the Government Palace on 1 June 2020 regarding the alleged irregularities.[127]

.png.webp)

According to IDL-Reporteros, lobbyist Karelim López provided opposition lawmaker Edgar Alarcon audio recordings.[130][131] On 10 September 2020, Alarcon, who faced possible parliamentary immunity revocation related to alleged acts of corruption, released audio recordings purporting that Vizcarra acted with "moral incapacity".[132][133] The recordings allegedly contain audio of Vizcarra instructing his staff to say that he met with Cisneros only on a limited number of occasions and audio of Cisneros saying that he influenced Vizcarra's rise to office and decision to dissolve congress.[132][133] Vizcarra responded to the release of the recordings stating "I am not going to resign. I am not running away" and that the "audios have been edited and maliciously manipulated; as you can see, they purposely seek to turn a job-related claim into a criminal or political act, wanting to take words out of context and intend to accuse me of non-existent situations. Nothing is further from reality".[133] In a vote on 11 September, impeachment proceedings against Vizcarra were approved by congress; 65 voted for, 36 voted against and 24 abstained.[127]

On 12 September 2020, renowned reporter Gustavo Gorriti wrote that Merino had contacted the Commanding General of the Peruvian Navy, Fernando Cerdán, notifying him that he was going to attempt to impeach Vizcarra and was hoping to assume the presidency.[134] Minister of Defense Jorge Chávez confirmed that Merino had tried to establish support with the Peruvian military.[134] A second report was later released that Merino had contacted officials throughout Peru's government while preparing to create a transitional cabinet.[135] Following the release of these reports, support for impeaching Vizcarra decreased among members of congress.

On 14 September, President Vizcarra filed a lawsuit in the Constitutional Court of Peru to block the 18 September impeachment vote, stating to during a press conference, "Why has the president of Congress communicated with top military officials, and even planned pseudo-cabinets who would take over? That is conspiracy, gentlemen."[136] Minister of Foreign Affairs Mario Lopez also released a statement that Vizcarra's government had prepared to call upon the Organization of American States' Inter-American Democratic Charter if Vizcarra were to be impeached, with the charter stating "when the government of a member state considers that its democratic political institutional process or its legitimate exercise of power is at risk, it may request assistance from the Secretary General or the Permanent Council for the strengthening and preservation of its democratic system".[137] On 18 September, Vizcarra gave a speech for twenty minutes after appearing before congress. Following ten hours of deliberation, 32 members of congress supported the motion to remove Vizcarra from the office of the presidency, 78 voted against his removal and 15 abstained from voting, with 87 votes of 130 being required for his removal.[138][139]

President of Congress Manuel Merino was criticized by critics regarding how he hastily pushed for impeachment proceedings against Vizcarra. If Vizcarra were to be removed from office, Merino would assume the presidential office given his position in congress and due to the absence of vice presidents for Vizcarra.[lower-alpha 2]

Further revelations showed that ethnocacerist leader Antauro Humala, brother of former president Ollanta Humala, had used his Union for Peru party and its lawmakers as proxies in order to overthrow Vizcarra from power, raising concerns for possible anti-democratic activities and other intent.[2][146]

Removal

After the first attempt failed, Edgar Alarcón of Union for Peru raised a new vacancy request in October 2020, based on the alleged acts of corruption by Vizcarra when he was regional Governor of Moquegua, which includes the testimony of an applicant to an effective collaborator in the "Construction Club Case" who stated that Obrainsa company paid him 1 million soles and three other aspiring effective collaborators also point out that he received 1.3 million soles from the Ingenieros Civiles y Contractors Generales SA consortium (ICCGSA), and Incot for the tender of the project for the construction of the Regional Hospital of Moquegua in 2013.[147] The new impulse to the vacancy motion came, then, at the initiative of the left party Unión por el Perú, Frente Amplio, Podemos Peru, Popular Action and a number of independents. The motion received 27 signatures, surpassing the minimum threshold required to pose an impeachment inquiry (26 congressmen). The motion was presented to Congress on 20 October 2020.[148] A minimum of 52 votes from Congress is required to initiate impeachment proceedings.[149]

On 25 October, Walter Martos announced that the Armed Forces “[will not] allow the rule of law to be broken with such need of the people. At this moment, five months before the elections,” which was highly controversial because Article 169 of the Political Constitution of Peru states that the Armed Forces and National Police are not deliberative and are subordinate to the constitutional process.[150] On October 27, Martos said that his statements were misinterpreted and stated that "We will never use [in reference to the government] the Armed Forces in political acts beyond their function."[151]

On 2 November, the admission of the vacancy motion was debated in the plenary session of Congress, at the end of which the plenary session of Congress proceeded to vote on the motion, obtaining 60 votes in favor of starting the vacancy process, 40 votes in against and 18 abstentions. The motion received the unanimous support of the Union for Peru, other parliamentary groups decided to vote freely without a collegiate consensus, the parliamentarians of Alliance for Progress and the Purple Party were against, the parliamentarians of FREPAP and 3 legislators from other benches abstained.[152]

Vizcarra minimized the vacancy motion, saying he trusted that in Parliament "sanity will prevail" and pointed out that "The only thing that we do not accept is that among the arguments they put in the vacancy motion, is that they use that transparent elections are not guaranteed. Please. That we do not accept. What we are doing here is guaranteeing totally transparent elections, because we do not participate in the elections. What greater transparency of this? ". He also accused some political parties of wanting to affect the general elections of 2021 since" they have no chance in the elections."[153] Nevertheless, Merino ratified defense of the planned elections day. Likewise, the president of the Council of Ministers Walter Martos pointed out that "a group of congressmen is breaking the Constitution" and considered that it is "tremendously irresponsible" that a second vacancy motion is raised.[153]

On the other hand, part of the congressmen of the Broad Front, specifically the congressmen Mirtha Vásquez and Rocío Silva Santisteban, expressed that they would not support the vacancy motion and issued a statement in which they said that "We cannot and do not want to stop putting life first, and especially life, at the risk of a fresh start to change health strategies that could lead to more and more deaths.[154]

Reports emerged following the vote from IDL-Reporteros that multiple congressmen pledged support to Vizcarra and later voted for his removal on 9 November.[155] While visiting Cajamarca on 6 November, Vizcarra did not appear worried about the vacancy vote according to one source, though some on the trip with Vizcarra appeared distant and refused to be in photographs with the president.[155] Somos Peru congress woman Felícita Tocto told Vizcarra that she would vote against the vacancy and encourage colleagues to do the same, though she would later vote in favor of his removal.[155]

On 9 November, initial discussions between Vizcarra and congressmen left him feeling positive as he appeared in Congress.[155] While at the legislative palace, Vizcarra criticized legislators who sought to vacate him from office, saying that sixty-eight congressmen were being investigated for alleged crimes themselves.[155] Vizcarra also said that the contracts in question were administered by an agency assigned by the United Nations, not his own office.[156] Ministerial staff stated that following Vizcarra's comments, the dozens of legislators that Vizcarra mentioned became determined to convince other members of congress to support votes for his removal, making strong arguments against Vizcarra.[155]

Hans Troyes of Popular Action reported that in the intermission room of the legislative palace, those in support of Vizcarra's removal told legislators that said they wanted to abstain or vote against the president's removal that they would refuse to sign their bills proposed in congress.[155] After returning from a trip to Junín after his speech in congress, Vizcarra received a call from César Acuña–who had told Vizcarra his Alliance for Progress party would not support his removal–with Acuña warning Vizcarra that his party would vote in support of his removal.[155] Vizcarra did not propose any defense to Acuña and ended the call shortly after learning this information.[155]

Shortly before the vacancy vote, Vizcarra and his ministerial staff learned that many congressmen had turned away from supporting him and calls to legislators were not being answered.[155] After learning what the outcome of the vote would be, Vizcarra gathered his ministers at the Government Palace at 7:30pm PET, telling those close to him "Up to here and no more ... I'm tired", telling ministers "I don't want to give the impression that I want to cling to power".[155] He then spoke to the public and departed from the Government Palace on the same night.[157]

The controversial removal of Vizcarra was defined as a coup by many Peruvians,[158] political analysts[159] and media outlets in the country.[160][161][162][163][164] Revelations were later made again of Antauro Humala's involvement, which raised even more concerns about possible systemic corruption.[146]

Merino presidency

Following Vizcarra's controversial removal from office, it was announced that Manuel Merino would assume the presidency, flaring up unrest.[165][166] Merino was inaugurated at 10:42 a.m. (Peru Time) on 10 November 2020, in the midst of protests across the country against his ascension to the presidency.[167][168][169][170][171] The following day, under the pressure of forming a new government, he named Ántero Flores Aráoz, a conservative politician and former Minister of Defense under former President Alan García, as Prime Minister.[172][173][174] The Secretary General of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro, expressed his concern about the issue and "reiterates that it is the responsibility of the Constitutional Court of Peru to rule on the legality and legitimacy of the institutional decisions adopted."[175]

A march, beginning at 5 PM PET on 12 November, occurred throughout Peru to demand the resignation of President Manuel Merino, with a primary location being at Plaza San Martín.[176] Richard Cisneros, who was the singer involved in Vizcarra's first impeachment scandal, arrived at the plaza minutes before the march began, angering protesters who threw objects at him until he took refuge inside a nearby fast food store.[177] The newly named Minister of Justice, Delia Muñoz, described calls for protests as "propaganda" while new Minister of Labor Juan Sheput falsely said "the protests are waning" and told the public that businesses would be hurt by the protests.[178]

Following the death of two protesters during clashes on 14 November,[179] Merino stepped down as president, citing that he acted within the law when he was sworn into office the previous Tuesday and that he would "do everything in my power to guarantee a constitutional succession."[180]

Sagasti presidency

On 16 November 2020, Francisco Sagasti was elected by the legislature to be the new President of Congress. Due to vacancies in the position of President and Vice President, he became President of Peru by the line of succession.[181] Upon taking office, he established his four main priorities for his temporary tenure; the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru, combatting corruption within the country, creating a stable economy and the promotion of education to rural areas.[182] Support for Sagasti's presidency was expressed by Chile, the European Union, United Kingdom and the United States.[183] Sagasti, as well as the attorney general, launched a probe against Manuel Merino for possible human rights violations.[184]

Like preceding presidents, Americas Quarterly wrote that Sagasti faced difficult relations with congress and that he will need to manage the effects of the two governments before him, including holding those responsible for violently responding to protests accountable for their actions.[124] Sagasti attempted to reform the leadership of the National Police due to their use of violence during protests, removing Commander General Orlando Velasco from leading the National Police.[185] Eighteen additional generals of the National Police resigned or were dismissed,[185][186] with Interior Minister Rubén Vargas resigning following the change to leadership.[3] Five days later Vargas' successor Cluber Aliaga would also resign in disagreement with Sagasti, defending the use of force by police saying that protesters initiated violence.[186] Sagasti was eligible to seek election for a full term, however the Purple Party nominated Julio Guzmán as their candidate for the 2021 Peruvian general election, with Sagasti on the ticket as Second Vice President.[119]

On November 27, former president Martín Vizcarra considered that Sagasti's replacement in the senior ranks "is not legal" and that the Sagasti government must "respect the institutional framework."[187] On December 1, the former president Francisco Morales Bermúdez with former Defense Ministers Julio Velásquez Giacarini, Roberto Chiabra, Jorge Kisic Wagner, Jorge Moscoso, Walter Martos and Jorge Chávez Cresta, 12 former heads of the Joint Command of the Armed Forces and former general commanders of the Army, Navy and of the Air Force described that the change in the Police was "illegal" and maintained that the decision "is contrary to the legal system, affects the morale of the National Police of Peru and undermines the work that this institution carries out.[188][189]

On December 2, journalist Nicolás Lúcar released the testimony of a former member of the deactivated Special Intelligence Group (GEIN) who revealed that an alleged half-brother of the Minister of the Interior was a leader of the Shining Path terrorist group;[190][191] information denied by Minister Vargas.[192] A few hours later, Rubén Vargas Céspedes resigned from the Ministry of the Interior.[193] He was replaced by Cluber Aliaga Lodtmann.

On 12 March 2021, the prosecutor Germán Juárez Atoche requested preventive detention for 18 months for former president Martín Vizcarra. This, within the framework of the investigation for the alleged crimes of aggravated collusion, improper passive bribery and illicit association to commit a crime.[194] The hearing was scheduled for 17 March,[195] where Judge María de los Ángeles Álvarez Camacho, after hearing both reasons from the prosecution and the defense of Vizcarra, was rejected [196] the request for preventive detention and appearance with restrictions was imposed.[197]

2021 elections and controversy

The 2021 elections contained the most amount of candidates of any recent elections, containing almost 18 candidates. Among them were Pedro Castillo, who had led the 2017 Teacher's strike; Keiko Fujimori; and businessman Rafael López Aliaga. Castillo's campaign with the Communist Free Peru Party, which often promoted the views of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez, brought controversy due to their views regarding Venezuelans in the country,[198][199][200] as well as campaigning for the expulsion of DEA agents[201] and the pardon of rebel leader Antauro Humala.[202][203]

On 23 May, a mass killing of eighteen people occurred in San Miguel del Ene, a rural area in the Vizcatán del Ene District of Satipo Province.[204] Along with the corpses, some of which were burned, leaflets signed by the MPCP were found, featuring the hammer and sickle and defining the attack as a social cleansing operation. The leaflets also called for a boycott of the 6 June elections and accused those who voted for Keiko Fujimori and her Popular Force party of treason. The military quickly accused Shining Path of the attack, although they were allegedly referring to the MCPC. However, no formal investigation had been performed before the links to Shining Path were claimed. OjoPúblico described the media release by the military as "an inaccurate reference to the Shining Path."

The attack and subsequent media coverage would provide increased support for Fujimori, whose rhetoric aligned Castillo with armed communists.[205] The Fujimori campaign used the attack as a springboard for support, pointing to alleged ties between MOVADEF, a Shining Path political group, and Castillo, attempting to align him to the attack. Fujimori expressed condemnation against the attack during a press conference in Tarapoto as well as regret that "bloody acts" still happened in the country and her condolences to the relatives of the victims.[206] Pedro Castillo also condemned the killings during a rally in Huánuco, expressing solidarity towards the relatives of the victims and also urging the National Police to investigate the attack to clarify the events.[207] Vladimir Cerrón, Secretary General of Free Peru, stated that "the right-wing needed [Shining] Path to win"; Cerrón deleted the tweet moments later while condemning any act of terrorism.[208] Prime Minister Nuria Esparch, who held the position of the Ministry of Defense, condemned the attack and guaranteed that the electoral process would take place normally.[209]

The election also saw the emergence of many far-right candidates.[7] Regarding the first round of presidential elections, Javier Puente, assistant professor of Latin American Studies at Smith College in the North American Congress on Latin America wrote: "With a baffling number of candidates – 18 in total – the 2021 presidential ballot included convicted felons, presumed money launderers, xenophobes, a fascist billionaire, an overrated and outdated economist, a retired mediocre footballer, a person accused of murdering a journalist, and other colorful figures. The vast majority of candidates represented the continuation of the neoliberal economic model that has been responsible for decades of meager financial performance and unequal growth."[210] Puente stated that only three leftist candidates proposed alternatives to the neoliberal politicians (Veronika Mendoza, Marco Arana, and Pedro Castillo), describing Castillo as "far from being a 'comrade' who will champion leftist demands, Castillo is the new face of an anti-system impulse. ... Only in a neoliberal system that outcasts any form of market dissent as radical would a figure like Castillo acquire a role as a leftist."[210]

The Americas Quarterly argues that such behavior resulted with less support for the leftist candidate Verónika Mendoza and promoted political polarization within Peru.[132] With the ongoing political crisis that saw in the span of two years the dissolution of the Congress of Peru and the removal of three presidents (Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Martín Vizcarra, and Manuel Merino), concerns were raised among analysts about the increased political polarization's relationship with Peru's democratic stability.[133] Lead researcher of pollster Institute of Peruvian Studies, Patricia Zárate, stated: "I think the scenario that's coming is really frightening."[133]

As the second round of elections approached, Fujimori's campaign used fearmongering tactics to gain support of the middle and upper classes in Lima, accusing Castillo of attempting to institute communism in Peru and to follow the path of Hugo Chávez and Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela.[7] Some scholars have recognized the similarities of Fujimori and Castillo; both are cultural conservatives opposing same-sex marriage and abortion, as campaigning for the second round of elections began.[211] Olga González, associate dean of the Kofi Annan Institute for Global Citizenship at Macalester College, stated that the situation is more complex than "binaries" between social classes, although she acknowledged that such dichotomies "speak to how polarized the country is."[211]

In the second round of elections, Peru's major media networks were accused of aligning with Fujimori to discredit Castillo. Some news media allegedly disseminated fake news against Castillo.[120][9] Le Monde diplomatique wrote, "The privately owned media torpedoed Castillo incessantly with fake news, and not without rattling the Shining Path scarecrow". International media also stated that Peruvian news organizations polished Fujimori's image and praised her, as well as assisting her media campaign tactic which included attacks accusing Castillo of being linked to armed communist groups.[205] The Guardian described accusations linking Castillo to Shining Path as "incorrect", while the Associated Press said that allegations by Peruvian media of links to Shining Path were "unsupported."[212][213]

With the support of Mario Vargas Llosa and his son Álvaro Vargas Llosa's neoliberal Fundación International para la Libertad (FIL), Fujimori attempted to reshape her image as being more democratic.[214] Vargas Llosa ran and lost against Alberto Fujimori in Peru's 1990 elections,[215] and had previously criticized Fujimori, making statements such as "the worst option is that of Keiko Fujimori because it means the legitimation of one of the worst dictatorships that Peru has had in its history"[216] and that "Keiko is the daughter of a murderer and a thief who is imprisoned, tried by civil courts with international observers, sentenced to 25 years in prison for murder and theft. I do not want her to win the elections."[217][214]

After Castillo took the lead during the ballot-counting process, Fujimori promoted unproven claims of electoral fraud.[218][219][220][221] In a media event following election day, Fujimori alleged that a "series of irregularities" had occurred, presenting photographs and videos in an attempt to support her allegations, while also accusing Free Peru of attempting to "distort and delay" the election process.[219][221] Fujimori argued that it consisted in the challenge of polling stations where Fujimori would register a greater number of votes than his opponent, previous training talks by Free Peru in which they ask their representatives to arrive early at the polling stations to ensure control of the polling stations where titular members did not attend and irregularities in the vote count.[222] To support the complaints, Keiko's running mate, Luis Galarreta, assured that Free Peru did a "high number of challenges" to electoral acts in which Keiko was favoured so they could not be counted to the final estimate until they were evaluated first by the National Jury of Elections.[223] According to the complaint, over 1 300 voting acts were challenged by Free Peru;[220] however, the first claims were rebutted by national electoral entities.[224] After the resolution of the challenged votes and the acts observed by the Special Electoral Juries, the National Office of Electoral Processes published the total results on 15 June, in which Pedro Castillo surpassed Keiko Fujimori in number of votes.[225]

According to The Guardian, various international observers countered Fujimori's claims, stating that the election process was conducted in accordance with international standards.[219] Observers from the Inter-American Union of Electoral Organizations, the Organization of American States, and the Progressive International denied any instances of widespread fraud and praised the accuracy of the elections.[226][227] The Guardian also reported that analysts and political observers criticized Fujimori's remarks, noting that it made her appear desperate after losing her third presidential run in a ten-year period.[219] Fernando Tuesta, political scientist from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, stated: "It's extremely regrettable that when the result is not favourable, that the candidate talks about fraud. It's terrible, ... They have been talking about fraud because they don't want to respect the result."[219] On 9 June, Fujimori sought to have around 200,000 votes annulled and for 300,000 votes to be reviewed.[228]

Following reports of Castillo's apparent victory, Fujimori and her supporters made unsubstantiated claims of electoral fraud, leading obstructionist efforts to overturn the election with support of wealthy citizens of Lima.[229][220][9][219][230][231] The economic and political elites refused to recognize Castillo's ascent to the presidency,[7] with those among the more affluent, including former military officers and wealthy families, demanded new elections, promoted calls for a military coup, and utilized classist or racist rhetoric to support their allegations of fraud.[220] According to analysts, Peru was more susceptible to unrest as a result of Fujimori's narrative since democratic institutions are weaker in the nation.[220] Minor clashes occurred in Lima between Fujimori supporters from the capital city and Castillo supporters from other regions, with rondas campesinas equipped with sticks and machetes arriving in the Historic Centre of Lima to defend Castillo's election and dissuade Fujimori protesters.[229] Fujimori's response to Castillo's victory was also to portray her movement as defending democracy and assumed a nationalist image, adopting the Peru national football team uniform and colors during rallies.[214] This intensified political polarization between urban and rural Peruvians, portraying rich, white individuals as democratic while identifying indigenous poor individuals as communists.[214]

After exit polls gave the victory to Keiko Fujimori over Pedro Castillo, supporters of Free Peru mobilized to the offices of the ONPE to protest against a possible fraud against their candidate,[232] bringing banners saying "no to the fraud."[233] From Tacabamba, Cajamarca,[234] Castillo called upon his followers and supporters on Twitter to "defend the votes" and go to the streets to "defend democracy."[235] Protests against Fujimori and an alleged fraud took place in cities such as Juliaca, Puno, and Ilave.[236]

After the publication of the quick count and the first official results, protests by supporters of both Free Peru and Popular Force took place.[237] Amid the fraud accusations and the final vote count, there were nearly daily protests and marches, mostly in the capital Lima.[238] Besides Fujimori supporters, groups opposed to Castillo, mobilized by the fear of communism or aversion to the left wing, mobilized asking for the annulment of the elections.[239] Among the opposition groups there were anti-communists, far-right followers, and neo-Nazi groups, including Acción Legionaria (Legionary Action).[239] During a mobilization in the San Martín Square in Lima, rondas campesinas supportive of Castillo carried machetes with them.[240] On 14 July, several pro-Fujimori protesters gathered at the Government Palace demanding an audit of the election. Protesters clashed with the National Police of Peru, and Health Minister Óscar Ugarte and Housing Minister Solangel Fernández were attacked during the protests.[241][242] On 15 July, Sagasti reaffirmed that there was no evidence of voter fraud.[243]

Senior fellow of the Washington Office on Latin America Jo Marie Burt described the overturn attempts as "a slow-motion conspiracy to prevent Castillo from becoming president", with The Guardian reporting that if Castillo was prevented from becoming president by 28 July 2021, a new election would be initiated.[120] Fujimori's statements about possibly overturning the election, along with her use of fake news and legal challenges, were also described as being inspired by the attempts to overturn the 2020 U.S. presidential election by former U.S. president Donald Trump.[218][220][9][230][231] According to Cornell University professor of Latin American politics Kenneth Roberts, "[w]hen the credibility is called into question the way it has been by Trump and the Republicans in the U.S., it creates a bad example that other leaders and countries can follow, providing a template to change results they don't like."[230][214]

To avoid the questions of election legitimacy, election authorities in Peru approved the use of election monitoring.[244] In total, one hundred and fifty observers (ninety-nine in Peru and fifty-one abroad) were approved to observe elections throughout Peru.[244] The origin of the observers were from twenty-two different countries, with thirty-five observers from the Organization of American States, while others were from Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Spain, Switzerland, the United States, and Uruguay.[244] Observer approval required providing election authorities observation plans; these plans included protocols to inform authorities of crimes, violations of electoral law or any complaints they collected.[244] Observers were then responsible with providing an official, final report to authorities.[244] According to OjoPúblico, "the observers carry out the review of the activities of election day, ranging from the installation of the voting tables, the conditioning of the secret chambers, the conformity of the ballots, the minutes, the amphorae and any other electoral material, to the counting, the counting of the vote and the transfer of the electoral records at the end of the day."[244]

On 10 June, the Peruvian Prosecution asked for the detention of Keiko on charges of violating the conditional liberty that she was granted during the open criminal process against her.[245] On 17 June, Fujimori repeated claims of voter fraud.[246] On 28 June, Fujimori traveled to the Government Palace and personally delivered demands to President Francisco Sagasti to initiate an audit of the results by international entities.[3] On 30 June, several members of the Popular Force party traveled to the OAS Building in Washington, D.C., to publicize the voter fraud claims, with sociologist Francesca Emanuele condemning them as "coup plotters" during a press conference.[247][248] On 2 July, Sagasti rejected a request to audit the second round of the election, and Fujimori accused Sagasti of abdicating his "great responsibility to ensure fair elections."[249] On 19 July, Fujimori admitted her defeat but reaffirmed that "votes were stolen" from her.[250]

On 18 June, former Supreme Court President Javier Villa Stein filed a complaint for protection by describing the ballot vote as "questioned", arguing an alleged "electoral process flawed by various acts that undermine the popular will" and asking the judiciary branch to "declare the election void."[251] Lawyer Renán Galindo Peralta requested that it be rejected outright considering it inadmissible because it did not fall under the Organic Law of Elections and because the judicial branch lacked the powers to annul elections.[252]

On 23 June, Luis Arce, a judge on the National Jury of Elections (JNE), resigned and alleged bias on the jury which had rejected ten Fujimori requests to annul Castillo votes. On its Twitter account, JNE rejected Arce's allegation of bias as "offensive", and said its judges were not allowed to resign in the middle of reviews of cases, so he would be suspended instead, and a provisional replacement found "to avoid delaying our work." Castillo's Free Peru party said the resignation was aimed at "preventing the proclamation of Pedro Castillo, thereby ignoring the popular vote, breaking democracy and installing a coup d'état with silk gloves." In the wake of Arce's resignation, a lawyer representing Fujimori said that the government should consider asking the Organization of American States (OAS) to audit the electoral process, as was done during the 2019 Bolivian political crisis. The OAS stated that its mission to the country had not found any issues in the conduct of the election.[253][254] Former candidate George Forsyth attributed it as part of the preparation of a "coup d'etat" and that Arce himself was "attacking democracy."[255]