2012 Negros earthquake

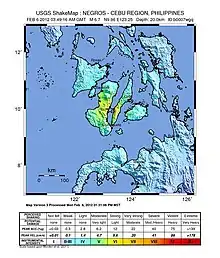

The 2012 Negros earthquake occurred on February 6 at 11:49 PST, with a body wave magnitude of 6.7 and a maximum intensity of VII (Destructive) off the coast of Negros Oriental, Philippines. The epicenter of the thrust fault earthquake[6] was approximately 72 kilometres (45 mi) north of Negros Oriental's provincial capital, Dumaguete.[7][8][9]

.svg.png.webp)  .svg.png.webp)  | |

| UTC time | 2012-02-06 03:49:12 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 600321522 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | February 6, 2012 |

| Local time | 11:49:11 PST[1] |

| Magnitude | 6.7 Mw 6.9 mb[1] |

| Depth | 10 km[1] |

| Epicenter | 9°58′N 123°08′E[1] |

| Type | Reverse or Thrust earthquake |

| Max. intensity | PEIS – VII (Destructive)[2] VII (Very strong) |

| Tsunami | No |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Aftershocks | 1,600+ (as of February 7, 2012, 7:45 PST)[3] |

| Casualties | 113 dead,[4][5] 112 injured |

Earthquake

The recorded intensities according to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) on the Earthquake Intensity Scale (PEIS) were VII in Dumaguete and V in Cebu.[10] The earthquake was felt as far as Mindanao in the provinces of Misamis and Lanao as well as Iligan.[11]

| Intensity

Scale |

Location[1] |

|---|---|

| VII | Dumaguete; Vallehermoso, Tayasan Negros Oriental |

| VI | La Carlota City and La Castellana, Negros Occidental; Argao, Cebu |

| V | Roxas City; Dao and Ivisan, Capiz; Iloilo City; Ayungon, Negros Oriental; Kanlaon City; Lapu-lapu City; Guimaras; Cebu City; San Carlos City; Bacolod City; Sagay City; Tagbilaran City; Candoni, Binalbagan, Negros Occidental. |

| IV | San Jose de Buenavista, Pandan, Anini-y, Patnungon, Antique; Kalibo, Aklan; Dipolog City; Sipalay, Negros Occidental; Ormoc City |

| III | Butuan City, Agusan del Norte; Legaspi City, Albay; Carmen, Cagayan de Oro; Tacloban City; Catbalogan; Saint Bernard, Southern Leyte; Masbate, Masbate; Cagayan de Oro City |

| II | Cabid-an, Sorsogon; Borongan, Eastern Samar; Mambajao, Camiguin |

| I | Pagadian City |

Geology

The Philippines lies within the Pacific Ring of Fire, which results in the archipelago experiencing frequent volcanic and seismic activity. The strongest earthquake to hit Negros occurred in 1948, but did not cause any damage.[12]

According to PHIVOLCS, the earthquake was caused by movement on a previously undiscovered fault.[13] However, according to an Environmental Sciences professor, this fault was already known to private geologists hired by the Negros Occidental government to create a land use map for the province.[14]

Tsunami warning

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) issued a level two tsunami alert, indicating that the public should be alert for "unusual waves", but no formal evacuation orders were issued. Tsunami waves reported to be as high as 5 metres (16 feet) were reported to have struck Barangays Martilo, Pisong, and Magtalisay in La Libertad. Coastal areas on the eastern seaboard of Negros Oriental from San Jose to Vallehermoso, and on the western side of Cebu from Badian to Barili were also reported to have been affected by the tsunami, though no widespread damage was reported.[15]

"Chona Mae" hoax

In Cebu City, rumors that a tsunami had hit the coastal villages of Ermita, Mambaling, and Pasil, with some reports saying that the tsunami had reached as far as Barangay Lahug,[16] forced residents into a panic. This is despite the fact that Cebu City, being on the eastern side of Cebu island, is opposite to the side facing Negros, the epicenter of the earthquake, and could not have been hit by a tsunami from the earthquake. The ensuing panic forced many businesses, schools, and offices in Cebu City to close for the day. Residents fled to the mountainous areas of the city, all the way up to Barangay Busay, more than 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) away from downtown Cebu City.

The cause of the panic was credited to, anecdotally, have come from someone who was calling out for someone named "Chona Mae", which eventually morphed mistakenly into a cry for "tsunami".[17] The earthquake, which happened nearly a year after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and its effects in Japan, was also attributed as a factor to the panic.[16]

Some residents of Dumaguete also scrambled to the mountain town of Valencia also because of rumors of a tsunami, which were later confirmed to be false. PHIVOLCS issued the tsunami alert at 14:30 PST, however no tsunami followed.[12]

Damage and effects

The degree and extent of damage caused by the earthquake was significant, with most of the damage sustained during the initial earthquake. The towns that experienced the most damage were the towns of Tayasan, Jimalalud, La Libertad, and the city of Guihulngan, in Negros Oriental. Several houses and buildings collapsed, while others sustained more minor damage. The earthquake also triggered numerous landslides which buried houses and people, including in the areas of Barangay Solongon, La Libertad and Planas, Guihulngan.[10][12]

Telecommunication services were disrupted after the earthquake.[18]

Casualties

More than 100 people were killed in the earthquake, most of whom died as a result of landslides that struck villages in Negros Occidental.[4]

Water

Water was cut off in several places, primarily the isolated remote towns. Guihulngan, one of the cities affected by the earthquake, suffered extensive damage. Its water services, along with electricity and telecommunications, were reported to be cut off.[19]

Electricity

After the initial earthquake, the power supply was suddenly disrupted in affected areas after power lines were damaged. Power plants in Visayas tripped or shut down following the earthquake, although no major damage was sustained in transmission facilities. On February 8, power was restored in some areas.[3]

Transport

The transport network of some parts of Cebu and Negros Oriental suffered severe disruptions. Main arterial roads were damaged, although automobiles and people could still pass through. A small number of roads, especially in the mountainous territories, were thought to be destroyed. A total of three roads and ten bridges were destroyed.[20] Because of damage to roads and bridges, access to some remote villages was no longer possible.[21] Most of the damage experienced was in north Negros Oriental, which is more mountainous than the rest of Negros Oriental.[12]

Cultural and governmental properties

Among the properties destroyed by the earthquake were the public market and the courthouse of Guihulngan. The Aglipay Church in La Libertad also collapsed.[22]

References

- "Earthquake Bulletin No. 4: 6.9 Negros Earthquake". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. February 6, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "2012 Earthquake Bulletins". Interaksyon. February 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- Elias O. Baquero; Kevin A. Lagunda; Rebelander S. Basilan (February 8, 2012). "Phivolcs 7: Tsunami warning correct; sees more aftershocks". SunStar Cebu. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "Toll up to 113 in Philippine earthquake". Hindustan Times. February 20, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- "Quake's death toll breaches 100". Gulf News. February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- Rimando, Rolly E.; Rimando, Jeremy M.; Lim, Robjunelieaaa B. (November 14, 2020). "Complex Shear Partitioning Involving the 6 February 2012 MW 6.7 Negros Earthquake Ground Rupture in Central Philippines". Geosciences. 10 (11): 460. Bibcode:2020Geosc..10..460R. doi:10.3390/geosciences10110460.

- "Strong quake jolts Negros-Cebu; fatalities rising". ABS-CBN News. February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- "Magnitude 6.7 – NEGROS – CEBU REGION, PHILIPPINES". United States Geological Survey. February 6, 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- Ellalyn B. De Vera; Elena L. Aben; Mars W. Mosqueda Jr. (February 6, 2012). "Quake Jolts Visayas". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- Jun Pasaylo; Dennis Carcamo (February 7, 2012). "Death toll in Visayas quake continues to rise". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- Abigail Kwok; Joseph Ubalde; Lira Dalangin-Fernandez (February 6, 2012). "Number of casualties rises as 6.7 quake strikes off Negros". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- Virgil Lopez (February 7, 2012). "Quake toll rising but no deaths in Cebu". Sun.Star Cebu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- Hernandez, Zen (February 7, 2012). "Phivolcs probes new Negros fault line". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- BAP/JKV (February 11, 2012). "Negros fault line discovered since 2008". SunStar Cebu. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- "REMINISCENCE OF THE 2012 Ms6.9 NEGROS ORIENTAL QUAKE". www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph. Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- "EDITORIAL - Lessons from Chona Mae". The Freeman. February 7, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- Lachica, Immae (February 6, 2021). "Cebuanos recall their unforgettable "Chona Mae" experience from nine years ago". Cebu Daily News. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- "Strong earthquake jolts Visayas; 43 reported dead". BusinessWorld. February 6, 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "Quake Deaths Rise". Manila Bulletin. February 7, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "3 roads, 10 bridges in Visayas impassable after quake; damage estimated at P265.76M". GMA News. GMA News and Public Affairs. February 9, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- "Rescuers search for missing after Philippine quake". Reuters. February 7, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "Number of casualties rises as 6.9 quake strikes off Negros". Manila Bulletin. February 7, 2012. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

External links

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- ReliefWeb's main page for this event.