Vallehermoso, Negros Oriental

Vallehermoso, officially the Municipality of Vallehermoso (Cebuano: Lungsod sa Vallehermoso; Hiligaynon: Banwa sang Vallehermoso; Tagalog: Bayan ng Vallehermoso), is a 3rd class municipality in the province of Negros Oriental, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 40,779 people.[3]

Vallehermoso | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Vallehermoso | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname: All-Around Suburb | |

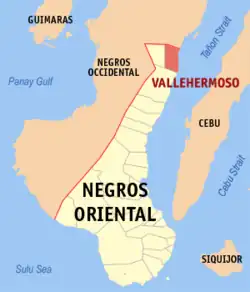

Map of Negros Oriental with Vallehermoso highlighted | |

OpenStreetMap | |

.svg.png.webp) Vallehermoso Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 10°20′N 123°19′E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Central Visayas |

| Province | Negros Oriental |

| District | 1st district |

| Barangays | 15 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Bayan |

| • Mayor | Marianne S. Gustilo (LP) |

| • Vice Mayor | Oliver S. Bongoyan (LP) |

| • Representative | Jocelyn Sy-Limkaichong |

| • Municipal Council | Members |

| • Electorate | 24,374 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 101.25 km2 (39.09 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 78 m (256 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 520 m (1,710 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[3] | |

| • Total | 40,779 |

| • Density | 400/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| • Households | 9,813 |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 3rd municipal income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 32.30 |

| • Revenue | ₱ 211.5 million (2020) |

| • Assets | ₱ 301.2 million (2020) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 190.1 million (2020) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 75.23 million (2020) |

| Service provider | |

| • Electricity | Negros Oriental 1 Electric Cooperative (NORECO 1) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 6224 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)35 |

| Native languages | Cebuano Hiligaynon Tagalog |

It is located right along the border with Negros Occidental. It is also roughly equidistant to three cities: north from Guihulngan, south from San Carlos, and east from Canlaon. Vallehermoso is 145 kilometres (90 mi) from Dumaguete.

Main source of livelihood is through fishing and farming, while the vast majority is still dependent upon third hand expenditures.

History

.png.webp)

The town was the official residence of the revolutionary leader and hero of Negros Oriental, Don Diego de la Viña y de la Rosa. Don Diego de la Viña shaped the beginnings of the municipality, “Valle hermoso” when he saw the beautiful valley.[5] In 1881, Don Diego de la Viña came from Negros Occidental in search of territories to conquer. The land he saw a top the mountains was the wilderness called Bagawines. Bukidnons, known to be unfriendly aboriginals inhabited the area. However, de la Viña sought the tribal chief, named Ka Saniko and truck barter.

For lands on coastal Bagawines, de la Viña offered wondrous articles from Iloilo, such as fine canes, well-crafted bolos and colorful patadyongs. Ka Saniko then moved further to Pinokawan. De la Viña with a number of Bukidnons cleared the land and constructed his residence, a casa tribunal and a chapel. In less than five years they transformed the valley into a hacienda of sugar cane, tobacco, coconut, rice and corn. He called it the “beautiful valley,” Vallehermoso. De la Viña bought, bartered and did everything else possible to enlarge his landholdings until it stretched from Molobolo on the boundary of Guihulngan, north to Macapso on the boundary of San Carlos and west to the slopes of Canlaon where he pastured his cattle and horses. He opened a road to Negros Occidental, which paved the way for his historic involvement in the local revolution against Spain. Don Diego de la Viña was an illustrado being born from a Spanish-Chinese parentage.

He grew up in Binondo, Manila but went to Basque, Asturias in Spain to earn his bachelor's degree in arts. Upon his return to Manila, he married a “Tagala” with whom he had four children. He brought them with him when he settled in Negros. Endowed with a pioneering spirit he searched for a place where he could establish a residence and fulfill his dream to carve out fortune. When he resided in Bagawines, he influenced the way of life of the bukidnons. They became civilized and tempered their warring tendencies. He inculcated with them the love of work and the idea of religion. He frowned on laziness. In the hacienda that De la Viña established, unemployment was not known. His work in the plantation made him physically strong and spiritually active. When his wife died, he remarried an Ilongga Doña Narcisa Geopano from the landed Geopano Clan.

He sired three children with his second wife. It was in the last quarter of 1898 when Don Diego de la Viña became involved in the revolution. His brother, Dr. Jose de la Viña was one of the delegates to the Malolos Congress. Dr. de la Viña regularly informed Don Diego of the latest development of the Republic government under Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo. Gen. Aguinaldo duly commissioned Don Diego de la Viña with the rank of General de Brigada, Commandante del Ejercito Filipino, Provincia de Negros Oriental. His son was also commissioned Lieutenant Colonel of the Infantry. He secretly trained his peasants how to handle a rifle. He turned their plowshares into bolos, “pinuti, “talibong”, “bahi”, spears and lances. Soon more and more men joined the group of de la Viña. He was soon around riding on a big white spotted horse during the “revolucionario”. De la Viña became known as the “Tigulang or the Grand Old Man”. He was considered a “cacique”, for he had the say in all appointments. He became the judge of local conflicts and designed the improvements for the place (source Negros Historian Prof. Penn Tulabing.Villanueva Larena, MPA a descendant of the Hermoso/ Olladas/ Serion and Bernus Clan an old Spanish family of this Town).

- The Arrival of Iloilo's Lopez Clan

During the depression years of the Sugar industry in the 1920s, a Spanish company named Tabacalera foreclosed haciendas which could not pay their credits. One of them was the Hacienda of Don Diego de la Viña clan. According to Zaffy Ledesma, a historian in the Lopez clan, the foreclosed property was sold to Don Vicente Lopez Sr. around 1924. Don Vicente belonged to the Lopez clan of Jaro. His hacienda was subsequently divided into two farms: Hacienda Dona Elena named after his wife and was inherited by his son, Vicente Lopez Jr. Hacienda Lilia, named after Tiking ( Vicente Jr.) sister, was inherited by Lilia Lopez Jison. Rosario Lopez, niece of Vicente Lopez Jr., married Arthur Cooper and became a landowner in Pinocauan, Vallehermoso.

- Creation of Municipality of Vallehermoso as a separate Municipality

The Municipality of Vallehermoso was created by virtue of Executive Order No. 19 signed by former Pres. Manuel A. Roxas. "Upon the recommendation of the Provincial Board of Oriental Negros and the Secretary of the Interior, and pursuant to the provisions of section sixty-eight of the Revised Administrative Code, the twenty-four municipalities of the Province of Oriental Negros, as established by section thirty-eight of the Revised Administrative Code, are hereby increased to twenty-five, by segregating from the municipality of Vallehermoso the barrios of Panubigan, Linothangan, Masolog, and Budlasan with all the sitios composing these barrios, and the sitio of Lucap of the barrio of Malaiba, and organizing the same into an independent municipality under the name of Canlaon, with the seat of government in the sitio of Mabigo, barrio of Panubigan."[6]

- Modern Times

On June 3, 2014, Monsignor Patrick Daniel Y. Parcon was appointed as the Bishop-elect of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Talibon, Bohol. Bishop Parcon, born in Vallehermoso in 1961, is a descendant of the Parcon clan in Sitio Tubod, Barangay Puan. He now holds the record of being the first son of Vallehermoso to be consecrated as Bishop, the first son of the Diocese of San Carlos with Vallehermoso as part of it, to be honored to assume the order of such title by Pope Francis.[7]

Geography

Barangays

Vallehermoso is politically subdivided into 15 barangays. Each barangay consists of puroks and some have sitios.

- Bagawines

- Bairan

- Don Espiridion Villegas

- Guba

- Cabulihan

- Macapso

- Malangsa

- Molobolo

- Maglahos

- Pinucauan

- Poblacion

- Puan

- Tabon

- Tagbino

- Ulay

Climate

| Climate data for Vallehermoso, Negros Oriental | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29 (84) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 100 (3.9) |

75 (3.0) |

90 (3.5) |

101 (4.0) |

183 (7.2) |

242 (9.5) |

215 (8.5) |

198 (7.8) |

205 (8.1) |

238 (9.4) |

194 (7.6) |

138 (5.4) |

1,979 (77.9) |

| Average rainy days | 14.9 | 11.3 | 14.5 | 17.4 | 26.4 | 28.4 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 26.9 | 28.4 | 24.2 | 17.2 | 265.6 |

| Source: Meteoblue[8] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1918 | 9,726 | — |

| 1939 | 21,677 | +3.89% |

| 1948 | 22,119 | +0.22% |

| 1960 | 22,932 | +0.30% |

| 1970 | 20,418 | −1.15% |

| 1975 | 23,326 | +2.71% |

| 1980 | 25,043 | +1.43% |

| 1990 | 27,945 | +1.10% |

| 1995 | 31,110 | +2.03% |

| 2000 | 33,914 | +1.87% |

| 2007 | 34,933 | +0.41% |

| 2010 | 36,943 | +2.06% |

| 2015 | 38,259 | +0.67% |

| 2020 | 40,779 | +1.26% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[9][10][11][12] | ||

People in Vallehermoso are mostly farmers and fishermen while the minorities are average earners dependent upon the employment opportunities yielded by the government and the business sector. At least half of the residents in the Central Vallehermoso are graduate in secondary education while a considerable number are professionals in the fields of Education and basic civic services.

Language

Cebuano is the main dialect of Vallehermoso but Hiligaynon is also spoken as the municipality borders Negros Occidental.

Economy

Vallehermoso is composed mostly of Agricultural lands typically good for growing almost all kinds of crops although much of the uses of these agricultural areas are invested on Sugarcane Farming. Corn is also another product in the area hence the people are largely dependent upon corn as their staple food. Coconut is also another source of income for most of the farmers through “tuba” or Coconut Wine, Vinegar and Lambanog. Ingenious materials such as broomsticks, bags and fashion accessories are also being made by the town's people as another source of income. Some other agricultural products such as; Banana, Cassava, Rice and coffee are also abundant in the area.

Tourism

- Annual Town Fiesta: May 15

- Chartered day celebration: January 1 and 2

Education

The public schools in the town of Vallehermoso are administered by one school district under the Schools Division of Guihulngan City.

Elementary schools:

- Bairan Elementary School — Bairan

- Banban Elementary School — Sitio Banban, Guba

- Cabulihan Elementary School — Cabulihan

- Dominador A. Paras Memorial Elementary School — Tagbino

- Don Esperidion Villegas Elementary School — Don Esperidion Villegas

- Don Julian dela Viña Villegas Elementary School — Sitio Bay-ang, Tabon

- Don Vicente Lopez Sr. Memorial School — Bagawines

- Guba Elementary School — Guba

- Macapso Elementary School — Macapso

- Maglahos Elementary School — Maglahos

- Malangsa Elementary School — Malangsa

- Molobolo Elementary School — Molobolo

- Paliran Elementary School — Sitio Paliran, Pinocawan

- Pinucauan Elementary School — Pinocawan

- Puan Elementary School — Puan

- Puti-an Elementary School — Sitio Puti-an, Pinocawan

- Tabon Elementary School — Tabon

- Tolotolo Elementary School — Sitio Tolotolo, Ulay

- Ulay Elementary School — Ulay

- Vallehermoso Central Elementary School — D. dela Viña Street, Poblacion

High schools:

- Guba High School — Guba

- Pinucauan High School — Pinocawan

- Rafaela R. Labang National High School (formerly Tagbino NHS) — Tagbino

- Tagbino Senior High School — Tagbino

- Vallehermoso National High School — Nat'l Highway, Poblacion

Private Schools

- St. Francis High School — Nat'l Highway, Poblacion

Notable people

- Bishop Daniel Patrick Yee Parcon - current bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Talibon in Bohol

References

- Vallehermoso, Maria Teresa Z. Lopez 2011 Retrieved 12 October 2019

- life story of Don Diego de la Vina, Leonaga Larena, Tulabing, 1990,Retrieved 12 October 2019

- Larena, Josefino Jr. T. Historia Politica de Vallehermoso 2011,Retrieved 18 October 2018

- Municipality of Vallehermoso | (DILG)

- "2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Quezon City, Philippines. August 2016. ISSN 0117-1453. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- Census of Population (2020). "Region VII (Central Visayas)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- "PSA Releases the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Rodriguez, Caridad Aldecoa (31 March 1986). "Don Diego de la Vina and the Philippines Revolution in Negros Oriental". Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. 34 (1): 61–76.

- "Executive Order No. 19, s. 1946 | GOVPH". 11 October 1946.

- Vatican Information Service (VIS)Other Pontifical Acts June 3, 2014

- "Vallehermoso: Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Meteoblue. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Census of Population (2015). "Region VII (Central Visayas)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region VII (Central Visayas)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. National Statistics Office. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Region VII (Central Visayas)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. National Statistics Office.

- "Province of". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- "Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 29 November 2005.

- "2003 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 23 March 2009.

- "City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates; 2006 and 2009" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 3 August 2012.

- "2012 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 31 May 2016.

- "Municipal and City Level Small Area Poverty Estimates; 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. 10 July 2019.

- "PSA Releases the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Other Sources