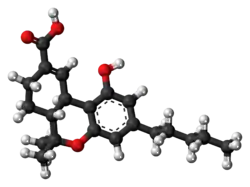

11-Nor-9-carboxy-THC

11-Nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-COOH-THC or THC-COOH), often referred to as 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC or THC-11-oic acid, is the main secondary metabolite of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which is formed in the body after cannabis is consumed.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Variable |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable |

| Metabolism | Variable |

| Elimination half-life | 5.2 to 6.2 days [1] |

| Excretion | Variable |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H28O4 |

| Molar mass | 344.451 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Metabolism and detection

11-COOH-THC is formed in the body by oxidation of the active metabolite 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC) by liver enzymes. It is then metabolized further by conjugation with glucuronide,[2] forming a water-soluble congener which can be more easily excreted by the body.[3]

11-COOH-THC has a long half-life in the body of up to several days (or even weeks in very heavy users),[4][5][6] making it the main metabolite tested for blood or urine testing for cannabis use. More selective tests are able to distinguish between 11-OH-THC and 11-COOH-THC, which can help determine how recently cannabis was consumed;[7][8] if only 11-COOH-THC is present then cannabis was used some time ago and any impairment in cognitive ability or motor function will have dissipated, whereas if both 11-OH-THC and 11-COOH-THC are present then cannabis was consumed more recently and motor impairment may still be present.

Some jurisdictions where cannabis use is decriminalized or permitted under some circumstances use such tests when determining whether drivers were legally intoxicated and therefore unfit to drive, with the comparative levels of THC, 11-OH-THC and 11-COOH-THC being used to derive a "blood cannabis level" analogous to the blood alcohol level used in prosecuting impaired drivers.[9] On the other hand, in jurisdictions where cannabis is completely illegal, any detectable levels of 11-COOH-THC may be deemed to constitute driving while intoxicated, even though this approach has been criticized as tantamount to prohibition of "driving whilst being a recent user of cannabis" regardless of the presence or absence of any actual impairment that might impact driving performance.

Effects

While 11-COOH-THC does not have any psychoactive effects in its own right, it may still have a role in the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of cannabis,[10][11][12] and has also been shown to moderate the effects of THC itself which may help explain the difference in subjective effects seen between occasional and regular users of cannabis.[13][14]

Legal status

The legal status of 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC varies among jurisdictions.

Australia

11-COOH-THC is a Schedule 8 prohibited substance in Western Australia under the Poisons Standard (July 2016).[15] A schedule 8 substance is a controlled Drug – Substances which should be available for use but require restriction of manufacture, supply, distribution, possession and use to reduce abuse, misuse and physical or psychological dependence.[15]

United States

Because 11-COOH-THC is substantially similar to the Schedule I controlled substance THC, possession or sale of 11-COOH-THC could be subject to prosecution under the Federal Analog Act.

See also

- Ajulemic acid, a synthetic analog of 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC

- Cannabis drug testing

References

- Schwilke EW, Schwope DM, Karschner EL, Lowe RH, Darwin WD, Kelly DL, et al. (December 2009). "Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxy-THC, and 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC plasma pharmacokinetics during and after continuous high-dose oral THC". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (12): 2180–2189. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.122119. PMC 3196989. PMID 19833841.

- Skopp G, Pötsch L (February 2002). "Stability of 11-nor-delta(9)-carboxy-tetrahydrocannabinol glucuronide in plasma and urine assessed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Clinical Chemistry. 48 (2): 301–306. doi:10.1093/clinchem/48.2.301. PMID 11805011.

- Law B, Mason PA, Moffat AC, King LJ (1984). "Confirmation of cannabis use by the analysis of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in blood and urine by combined HPLC and RIA". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 8 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1093/jat/8.1.19. PMID 6323852.

- Huestis MA, Mitchell JM, Cone EJ (October 1995). "Detection times of marijuana metabolites in urine by immunoassay and GC-MS". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 19 (6): 443–449. doi:10.1093/jat/19.6.443. PMID 8926739.

- Pope HG, Gruber AJ, Hudson JI, Huestis MA, Yurgelun-Todd D (October 2001). "Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users". Archives of General Psychiatry. 58 (10): 909–915. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. PMID 11576028.

- Dietz L, Glaz-Sandberg A, Nguyen H, Skopp G, Mikus G, Aderjan R (June 2007). "The urinary disposition of intravenously administered 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 29 (3): 368–372. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31805ba6fd. PMID 17529896. S2CID 25321236.

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ (1992). "Blood cannabinoids. II. Models for the prediction of time of marijuana exposure from plasma concentrations of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THCCOOH)". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 16 (5): 283–290. doi:10.1093/jat/16.5.283. PMID 1338216.

- Huestis MA, Elsohly M, Nebro W, Barnes A, Gustafson RA, Smith ML (August 2006). "Estimating time of last oral ingestion of cannabis from plasma THC and THCCOOH concentrations". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 28 (4): 540–544. doi:10.1097/00007691-200608000-00009. PMID 16885722. S2CID 22536528.

- Ménétrey A, Augsburger M, Favrat B, Pin MA, Rothuizen LE, Appenzeller M, et al. (2005). "Assessment of driving capability through the use of clinical and psychomotor tests in relation to blood cannabinoids levels following oral administration of 20 mg dronabinol or of a cannabis decoction made with 20 or 60 mg Delta9-THC". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 29 (5): 327–338. doi:10.1093/jat/29.5.327. PMID 16105257.

- Burstein SH, Hull K, Hunter SA, Latham V (November 1988). "Cannabinoids and pain responses: a possible role for prostaglandins". FASEB Journal. 2 (14): 3022–3026. doi:10.1096/fasebj.2.14.2846397. PMID 2846397. S2CID 46552755.

- Doyle SA, Burstein SH, Dewey WL, Welch SP (August 1990). "Further studies on the antinociceptive effects of delta 6-THC-7-oic acid". Agents and Actions. 31 (1–2): 157–163. doi:10.1007/bf02003237. PMID 2178317. S2CID 23310488.

- Ujváry I, Grotenhermen F (2014). "11-Nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol – a ubiquitous yet underresearched cannabinoid. A review of the literature" (PDF). Cannabinoids. 9 (1): 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-20. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- Burstein S, Hunter SA, Latham V, Renzulli L (April 1987). "A major metabolite of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol reduces its cataleptic effect in mice". Experientia. 43 (4): 402–403. doi:10.1007/BF01940427. PMID 3032669. S2CID 22153383.

- Burstein S, Hunter SA, Latham V, Renzulli L (August 1986). "Prostaglandins and cannabis--XVI. Antagonism of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol action by its metabolites". Biochemical Pharmacology. 35 (15): 2553–2558. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90053-5. PMID 3017356.

- Poisons Standard July 2016 Comlaw.gov.au