Xerox Alto

The Xerox Alto is a computer that was designed from its inception to support an operating system based on a graphical user interface (GUI), later using the desktop metaphor.[7][8] The first machines were introduced on 1 March 1973,[9] a decade before mass-market GUI machines became available.

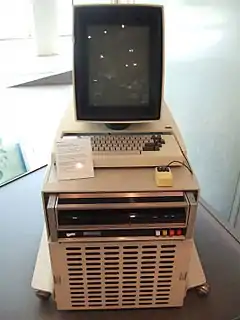

The monitor of the Xerox Alto has a portrait orientation. | |

| Developer | Xerox PARC |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Xerox PARC |

| Release date | March 1, 1973 |

| Introductory price | US$32,000 in 1979 (equivalent to $129,000 in 2022)[1][2] |

| Units shipped | Alto I: 120 Alto II: 2,000[3] |

| Media | 2.5 MB one-platter disk cartridge[4] |

| Operating system | Alto Executive (Exec) |

| CPU | TTL-based, with the ALU built around four 74181 MSI chips. It has user programmable microcode, uses big-endian format and a CPU clock of 5.88 MHz.[5][4] |

| Memory | 96[6] – 512 KB (128 KB for 4000 USD)[4] |

| Display | 606 × 808 pixels[4] |

| Input | Keyboard, 3-button mouse, 5-key chorded keyboard |

| Connectivity | Ethernet |

| Successor | Xerox Star |

| Related | ETH Lilith; Apple Lisa; Apollo/Domain |

The Alto is contained in a relatively small cabinet and uses a custom central processing unit (CPU) built from multiple SSI and MSI integrated circuits. Each machine cost tens of thousands of dollars despite its status as a personal computer. Only small numbers were built initially, but by the late 1970s, about 1,000 were in use at various Xerox laboratories, and about another 500 in several universities. Total production was about 2,000 systems.

The Alto became well known in Silicon Valley and its GUI was increasingly seen as the future of computing. In 1979, Steve Jobs arranged a visit to Xerox PARC, during which Apple Computer personnel would receive demonstrations of Xerox technology in exchange for Xerox being able to purchase stock options in Apple.[10] After two visits to see the Alto, Apple engineers used the concepts in developing the Apple Lisa and Macintosh systems.

Xerox eventually commercialized a heavily modified version of the Alto concepts as the Xerox Star, first introduced in 1981. A complete office system including several workstations, storage and a laser printer cost as much as $100,000, and like the Alto, the Star had little direct impact on the market.

History

.jpg.webp)

The first computer with a graphical operating system, the Alto built on earlier graphical interface designs. It was conceived in 1972 in a memo written by Butler Lampson, inspired by the oN-Line System (NLS) developed by Douglas Engelbart and Dustin Lindberg at SRI International (SRI). Of further influence was the PLATO education system developed at the Computer-based Education Research Laboratory at the University of Illinois.[11] The Alto was designed mostly by Charles P. Thacker. Industrial Design and manufacturing was sub-contracted to Xerox, whose Special Programs Group team included Doug Stewart as Program Manager, Abbey Silverstone Operations, Bob Nishimura, Industrial Designer. An initial run of 30 units was produced by Xerox El Segundo (Special Programs Group), working with John Ellenby at PARC and Doug Stewart and Abbey Silverstone at El Segundo, who were responsible for re-designing the Alto's electronics. Due to the success of the pilot run, the team went on to produce approximately 2,000 units over the next ten years.[12]

Several Xerox Alto chassis are now on display at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, one is on display at the Computer Museum of America in Roswell, Georgia, and several are in private hands. Running systems are on display at the System Source Computer Museum in Hunt Valley, Maryland. Charles P. Thacker was awarded the 2009 Turing Award of the Association for Computing Machinery on March 9, 2010, for his pioneering design and realization of the Alto.[13] The 2004 Charles Stark Draper Prize was awarded to Thacker, Alan C. Kay, Butler Lampson, and Robert W. Taylor for their work on Alto.[14]

On October 21, 2014, Xerox Alto's source code and other resources were released from the Computer History Museum.[15]

Architecture

The following description is based mostly on the August 1976 Alto Hardware Manual[16] by Xerox PARC.

Alto uses a microcoded design, but unlike many computers, the microcode engine is not hidden from the programmer in a layered design. Applications such as Pinball take advantage of this to accelerate performance. The Alto has a bit-slice arithmetic logic unit (ALU) based on the Texas Instruments 74181 chip, a ROM control store with a writable control store extension and has 128 (expandable to 512) KB of main memory organized in 16-bit words. Mass storage is provided by a hard disk drive that uses a removable 2.5 MB one-platter cartridge (Diablo Systems, a company Xerox later bought) similar to those used by the IBM 2310. The base machine and one disk drive are housed in a cabinet about the size of a small refrigerator; one more disk drive can be added via daisy-chaining.

Alto both blurred and ignored the lines between functional elements. Rather than a distinct central processing unit with a well-defined electrical interface (e.g., system bus) to storage and peripherals, the Alto ALU interacts directly with hardware interfaces to memory and peripherals, driven by microinstructions that are output from the control store. The microcode machine supports up to 16 cooperative multitasking tasks, each with fixed priority. The emulator task executes the normal instruction set to which most applications are written; that instruction set is similar to, but not the same as, that of a Data General Nova.[17] Other tasks serve the display, memory refresh, disk, network, and other I/O functions. As an example, the bitmap display controller is little more than a 16-bit shift register; microcode moves display refresh data from main memory to the shift register, which serializes it into a display of pixels corresponding to the ones and zeros of the memory data. Ethernet is likewise supported by minimal hardware, with a shift register that acts bidirectionally to serialize output words and deserialize input words. Its speed was designed to be 3 Mbit/s because the microcode engine could not go faster and continue to support the video display, disk activity and memory refresh.

Unlike most minicomputers of the era, Alto does not support a serial terminal for user interface. Apart from an Ethernet connection, the Alto's only common output device is a bi-level (black and white) cathode-ray tube (CRT) display with a tilt-and-swivel base, mounted in portrait orientation rather than the more common "landscape" orientation. Its input devices are a custom detachable keyboard, a three-button mouse, and an optional 5-key chorded keyboard (chord keyset). The last two items had been introduced by SRI's On-Line System; while the mouse was an instant success among Alto users, the chord keyset never became popular.

In the early mice, the buttons were three narrow bars, arranged top to bottom rather than side to side; they were named after their colors in the documentation. The motion was sensed by two wheels perpendicular to each other. These were soon replaced with a ball-type mouse, which was invented by Ronald E. Rider and developed by Bill English. These were photo-mechanical mice, first using white light, and then infrared (IR), to count the rotations of wheels inside the mouse.

Each key on the Alto keyboard is represented as a separate bit in a set of memory locations. As a result, it is possible to read multiple key presses concurrently. This trait can be used to alter from where on the disk the Alto boots. The keyboard value is used as the sector address on the disk to boot from, and by holding specific keys down while pressing the boot button, different microcode and operating systems can be loaded. This gave rise to the expression "nose boot" where the keys needed to boot for a test OS release required more fingers than you could come up with. Nose boots were made obsolete by the move2keys program that shifted files on the disk so that a specified key sequence could be used.

Several other I/O devices were developed for the Alto, including a TV camera, the Hy-Type daisywheel printer and a parallel port, although these were quite rare. The Alto could also control external disk drives to act as a file server. This was a common application for the machine.

Software

Early software for the Alto was written in the programming language BCPL, and later in Mesa,[2] which was not widely used outside PARC but influenced several later languages, such as Modula. The Alto used an early version of ASCII which lacked the underscore character, instead having the left-arrow character used in ALGOL 60 and many derivatives for the assignment operator: this peculiarity may have been the source of the CamelCase style for compound identifiers. Altos were also microcode-programmable by users.[16]

The Alto helped popularize the use of raster graphics model for all output, including text and graphics. It also introduced the concept of the bit block transfer operation (bit blit, BitBLT), as the fundamental programming interface to the display. Despite its small memory size, many innovative programs were written for the Alto, including:

- the first WYSIWYG typesetting document preparation systems, Bravo and Gypsy;

- the Laurel email tool,[18] and its successor, Hardy[19][20]

- the Sil vector graphics editor, used mainly for logic circuits, printed circuit board, and other technical diagrams;

- the Markup bitmap editor (an early paint program);

- the Draw graphical editor using lines and splines;

- the first WYSIWYG integrated circuit editor based on the work of Lynn Conway, Carver Mead, and the Mead and Conway revolution;

- the first versions of the Smalltalk environment

- Interlisp

- one of the first network-based multi-person video games (Alto Trek by Gene Ball).

There was no spreadsheet or database software. The first electronic spreadsheet program, VisiCalc, did not appear until 1979.

Diffusion and evolution

Technically, the Alto was a small minicomputer, but it could be considered a personal computer in the sense that it was used by one person sitting at a desk, in contrast with the mainframe computers and other minicomputers of the era. It was arguably "the first personal computer", although this title is disputed by others. More significantly (and perhaps less controversially), it may be considered to be one of the first workstation systems, with successors such as the Apollo workstations and systems by Symbolics (designed to natively run Lisp as a development environment.)[21]

In 1976 to 1977, the Swiss computer pioneer Niklaus Wirth spent a sabbatical at PARC and was excited by the Alto. Unable to bring back one of the Alto systems to Europe, Wirth decided to build a new system from scratch and he designed with his group the Lilith.[22] Lilith was ready to use around 1980, quite some time before Apple Lisa and Macintosh were released. Around 1985 Wirth started a complete redesign of the Lilith under the Name "Project Oberon".

In 1978, Xerox donated 50 Altos to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, Carnegie Mellon University,[2] and the University of Rochester.[23] The National Bureau of Standards's Institute for Computer Sciences in Gaithersburg, Maryland received one Alto in late 1978 along with Xerox Interim File System (IFS) file servers and Dover laser printers. These machines were the inspiration for the ETH Zuerich Lilith and Three Rivers Company PERQ workstations, and the Stanford University Network (SUN) workstation, which was eventually marketed by a spin-off company, Sun Microsystems. The Apollo/Domain workstation was heavily influenced by the Alto.

Following the acquisition of an Alto, the White House information systems department sought to lead federal computer suppliers in its direction. The Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP) issued a request for proposal for a computer system to replace the aging Office of Management and Budget (OMB) budget system, using Alto-like workstations, connected to an IBM-compatible mainframe. The request was eventually withdrawn because no mainframe producer could supply such a configuration.

In December 1979, Apple Computer's co-founder Steve Jobs visited Xerox PARC, where he was shown the Smalltalk-76 object-oriented programming environment, networking, and most importantly the WYSIWYG, mouse-driven graphical user interface provided by the Alto. At the time, he didn't recognize the significance of the first two, but was excited by the last one, promptly integrating it into Apple's products; first into the Lisa and then in the Macintosh, attracting several key researchers to work in his company.[24]

In 1980-1981, Xerox Altos were used by engineers at PARC and at the Xerox System Development Department to design the Xerox Star workstations.

Xerox and the Alto

Xerox was slow to realize the value of the technology that had been developed at PARC.[25] The Xerox corporate acquisition of Scientific Data Systems (SDS, later XDS) in the late 1960s had no interest to PARC. PARC built their own emulation of the Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-10 named the MAXC.[26] The MAXC was PARC's gateway machine to the ARPANET. The firm was reluctant to get into the computer business again with commercially untested designs, although many of the philosophies would ship in later products.

Byte magazine stated in 1981,[2]

It is unlikely that a person outside of the computer-science research community will ever be able to buy an Alto. They are not intended for commercial sale, but rather as development tools for Xerox, and so will not be mass-produced. What makes them worthy of mention is the fact that a large number of the personal computers of tomorrow will be designed with knowledge gained from the development of the Alto.

After the Alto, PARC developed more powerful workstations (none intended as projects) informally termed "the D-machines": Dandelion (least powerful, but the only to be made a product in one form), Dolphin; Dorado (most powerful; an emitter-coupled logic (ECL) machine); and hybrids like the Dandel-Iris.

Before the advent of personal computers such as the Apple II in 1977 and the IBM Personal Computer (IBM PC) in 1981, the computer market was dominated by costly mainframes and minicomputers equipped with dumb terminals that time-shared the processing time of the central computer. Through the 1970s, Xerox showed no interest in the work done at PARC. When Xerox finally entered the PC market with the Xerox 820, they pointedly rejected the Alto design and opted instead for a very conventional model, a CP/M-based machine with the then-standard 80 by 24 character-only monitor and no mouse.

With the help of PARC researchers, Xerox eventually developed the Xerox Star, based on the Dandelion workstation, and later the cost reduced Star, the 6085 office system, based on the Daybreak workstation. These machines, based on the 'Wildflower' architecture described in a paper by Butler Lampson, incorporated most of the Alto innovations, including the graphical user interface with icons, windows, folders, Ethernet-based local networking, and network-based laser printer services.

Xerox only realized their mistake in the early 1980s, after Apple's Macintosh revolutionized the PC market via its bitmap display and the mouse-centered interface. Both of these were copied from the Alto.[25] While the Xerox Star series was a relative commercial success, it came too late. The expensive Xerox workstations could not compete against the cheaper GUI-based workstations that arose in the wake of the first Macintosh, and Xerox eventually quit the workstation market for good.

References

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Wadlow, Thomas A. (September 1981). "The Xerox Alto Computer". Byte. Vol. 6, no. 9. p. 58. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "MP3 Audio of Ron Cude talking about the 1979 Boca Raton Alto Event". The DigiBarn Computer Museum. 2003. Archived from the original on 2020-09-18.

- "History of Computers and Computing, Birth of the modern computer, Personal computer, Xerox Alto". Archived from the original on 2020-12-05. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- "Alto I Schematics" (PDF). Bitsavers. p. 54. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Alto Operating System Reference Manual (PDF). Xerox PARC. 26 June 1975. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Koved, Larry; Selker, Ted (1999). "Room with a view (RWAV): A metaphor for interactive computing" (

PDF). IBM TJ Watson Research Center. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.1340.

PDF). IBM TJ Watson Research Center. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.1340. - Thacker, Charles P.; McCreight, Ed; Lampson, Butler; Sproull, Robert; Boggs, David (September 1981). "Alto: A personal computer". In Siewiorek, Daniel P.; Bell, C. Gordon; Newell, Allen (eds.). Computer Structures: Principles and Examples (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 549–572. ISBN 978-0-07-057302-4.

- "The Xerox Alto". Nathan's Toasty Technology page. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- "The Xerox PARC Visit". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-09-24. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- Dear, Brian (2017). The Friendly Orange Glow: The untold story of the PLATO System and the dawn of cyberculture. Pantheon Books. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-1-101-87155-3.

- "The History of the Xerox Alto". Carl J. Clement. March, 2002.

- Gold, Virginia (2010). "ACM Turing Award Goes to Creator of First Modern Personal Computer". Association for Computing Machinery. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ""2004 Recipients of the Charles Stark Draper Prize"". Archived from the original on 2010-11-05. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- McJones, Paul (2014-10-21). "Xerox Alto Source Code - The roots of the modern personal computer". Software Gems: The Computer History Museum Historical Source Code Series. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

With the permission of the Palo Alto Research Center, the Computer History Museum is pleased to make available, for non-commercial use only, snapshots of Alto source code, executables, documentation, font files, and other files from 1975 to 1987.

- "Alto Hardware Manual" (PDF). bitsavers.org. Xerox. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Thacker, Charles P.; McCreight, Edward M. (December 1974). Alto: A Personal Computer System (PDF) (Report). p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Brotz, Douglas K. (May 1981). "Laurel Manual" (PDF). Xerox. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- Ollig, Mark (October 31, 2011). "They could have owned the computer industry". Herald Journal. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- "Xerox Star". The History of Computing Project. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- "Personal Computer Milestones". Blinkenlights Archaeological Institute. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- "Lilith Workstation". Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Denber, Michel (February 1982). "Altos Gamesmen". Byte (letter). Vol. 7, no. 2. p. 28. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- "PBS Triumph of the Nerds Television Program Transcripts: Part III". PBS (Public Broadcasting System). Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- Smith, Douglas K.; Alexander, Robert C. (1988). Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, Then Ignored, the First Personal Computer. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0688069599.

- Fiala, Edward R. (May 1978). "The Maxc Systems". Computer. Vol. 11, no. 5. pp. 57–67. doi:10.1109/C-M.1978.218184. S2CID 16813696. Archived from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- Tomitsch, Martin (January 2003). "Trends and Evolution of Window Interfaces" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-03-03.

Further reading

- Alto user's handbook : September 1979. Palo Alto, Calif.: Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. 1979. OCLC 7271372 – via Internet Archive.

- Hiltzik, Michael A. (1999). Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0887309892.

- Brock, David C. (2023-03-01). "50 Years Later, We're Still Living in the Xerox Alto's World". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

External links

- Xerox Alto documents at bitsavers.org

- At the DigiBarn museum

- Xerox Alto Source Code - CHM (computerhistory.org)

- Xerox Alto source code (computerhistory.org)

- "Hello world" in the BCPL language on the Xerox Alto simulator (righto.com)

- The Alto in 1974 video

- A lecture video of Butler Lampson describing Xerox Alto in depth. (length: 2h45m)

- A microcode-level Xerox Alto simulator

- ContrAlto Xerox Alto emulator

- brainsqueezer/salto_simulator: SALTO - Xerox Alto I/II Simulator (github.com)

- SALTO-Xerox Alto emulator (direct download)

- ConrAltoJS Xerox Alto Online