Australian art

Australian art is any art made in or about Australia, or by Australians overseas, from prehistoric times to the present. This includes Aboriginal, Colonial, Landscape, Atelier, early-twentieth-century painters, print makers, photographers, and sculptors influenced by European modernism, Contemporary art. The visual arts have a long history in Australia, with evidence of Aboriginal art dating back at least 30,000 years. Australia has produced many notable artists of both Western and Indigenous Australian schools, including the late-19th-century Heidelberg School plein air painters, the Antipodeans, the Central Australian Hermannsburg School watercolourists, the Western Desert Art Movement and coeval examples of well-known High modernism and Postmodern art.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Australia |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Australia portal |

History

Indigenous Australia

The ancestors of Aboriginal Australians are believed to have arrived in Australia as early as 60,000 years ago, and evidence of Indigenous Australian art in Australia can be traced back at least 30,000 years.[1] Examples of ancient Aboriginal rock artworks can be found throughout the continent. Notable examples can be found in national parks, such as those of the UNESCO listed sites at Uluru and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, and the Gwion Gwion rock paintings in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Rock art can also be found within protected parks in urban areas such as Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Sydney.[2][3][4] The Sydney rock engravings are approximately 5000 to 200 years old. Murujuga in Western Australia has the Friends of Australian Rock Art advocating its preservation, and the numerous engravings there were heritage listed in 2007.[5][6]

In terms of age and abundance, cave art in Australia is comparable to that of Lascaux and Altamira in Europe,[7] and Aboriginal art is believed to be the oldest continuing tradition of art in the world.[8] There are three major regional styles: the geometric style found in Central Australia, Tasmania, the Kimberley and Victoria known for its concentric circles, arcs and dots; the simple figurative style found in Queensland; the complex figurative style found in Arnhem Land which includes X-Ray art.[9] These designs generally carry significance linked to the spirituality of the Dreamtime.[10]

William Barak (c.1824-1903) was one of the last traditionally educated of the Wurundjeri-Willam people who come from the district now incorporating the city of Melbourne. He remains notable for his artworks which recorded traditional Aboriginal ways for the education of Westerners (which remain on permanent exhibition at the Ian Potter Centre of the National Gallery of Victoria and the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery). Margaret Preston (1875–1963) was among the early non-indigenous painters to incorporate Aboriginal influences in her works. Albert Namatjira (1902–1959) is a famous Australian artist and an Arrernte man. His landscapes inspired the Hermannsburg School of art.[11] The works of Elizabeth Durack are notable for their fusion of Western and indigenous influences. Since the 1970s, indigenous artists have employed the use of acrylic paints – with styles such as the Western Desert Art Movement becoming globally renowned 20th-century art movements.

The National Gallery of Australia exhibits a great many indigenous art works, including those of the Torres Strait Islands who are known for their traditional sculpture and headgear.[12] The Art Gallery of New South Wales has an extensive collection of indigenous Australian art. In May 2011, the Director of the Place, Evolution, and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU) at Griffith University, Paul Taçon, called for the creation of a national database for rock art.[13] Paul Taçon launched the "Protect Australia's Spirit" campaign in May 2011 with the Australian actor Jack Thompson.[14] This campaign aims to create the very first fully resourced national archive to bring together information about rock art sites, as well as planning for future rock art management and conservation. The National Rock Art Institute would bring together existing rock art expertise from Griffith University, Australian National University, and the University of Western Australia if they were funded by philanthropists, big business and government. Rock Art Research is published twice a year and also covers international scholarship of rock art.

Early European depictions

The first artistic representations of the Australia scene by European artists were mainly natural history illustrations, depicting the distinctive flora and fauna of the land for scientific purposes, and the topography of the coast. Sydney Parkinson, the botanical illustrator on James Cook's 1770 voyage that first charted the eastern coastline of Australia, made a large number of such drawings under the direction of naturalist Joseph Banks. Many of these drawings were met with skepticism when taken back to Europe, for example claims that the platypus was a hoax. In the form of copies and reproductions, George Stubbs' 1772 paintings Portrait of a Large Dog and The Kongouro from New Holland—depicting a dingo and kangaroo respectively—were the first images of Australian fauna to be widely disseminated in Britain.

British colonization (1788–1850)

Early Western art in Australia, from British colonisation in 1788 onwards, is often narrated as the gradual shift from a European sense of light to an Australian one. The lighting in Australia is notably different from that of Europe, and early attempts at landscapes attempted to reflect this. It has also been one of transformation, where artistic ideas originating from beyond (primarily Europe) gained new meaning and purpose when transplanted into the new continent and the emerging society.[15]

Despite Banks' suggestions, no professional natural-history artist sailed on the First Fleet in 1788. Until the turn of the century all drawings made in the colony were crafted by soldiers, including British naval officers George Raper and John Hunter, and convict artists, including Thomas Watling.[16] However, many of these drawings are by unknown artists, most notably the Port Jackson Painter. Most are in the style of naval draughtsmanship, and cover natural history topics, specifically birds, and a few depict the infant colony itself.

Several professional natural-history illustrators accompanied expeditions in the early 19th century, including Ferdinand Bauer, who travelled with Matthew Flinders, and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, who travelled with a French expedition led by Nicolas Baudin. The first resident professional artist was John Lewin,[16] who arrived in 1800 and published two volumes of natural history art. Ornithologist John Gould was renowned for his illustrations of the country's birds.[16] In the late 19th century Harriet and Helena Scott were highly respected natural history illustrators[17] Lewin's Platypus (1808) represents the fine detail and scientific observation displayed by many of these early painters.

As well as inspiration in natural history, there were some ethnographic portraiture of Aboriginal Australians, particularly in the 1830s. Artists included Augustus Earle in New South Wales[16] and Benjamin Duterrau, Robert Dowling and the sculptor Benjamin Law, recording images of Aboriginal Tasmanians.

The most significant landscape artist of this era[15] was John Glover. Heavily influenced by 18th-century European landscape painters, such as Claude Lorraine and Salvator Rosa, his works captured the distinctive Australian features of open country, fallen logs, and blue hills.[18]

Conrad Martens (1801–1878) worked from 1835 to 1878 as a professional artist, painting many landscapes and was commercially successful. His work has been regarded as softening the landscape to fit European sensibilities.[16] His watercolour studies of Sydney Harbour are well regarded, and seen as introducing Romantic ideals to his paintings.[18] Martens is also remembered for accompanying scientist Charles Darwin on HMS Beagle (as had Augustus Earle).

Thomas Watling, A Direct North General View of Sydney Cove, 1794

Thomas Watling, A Direct North General View of Sydney Cove, 1794 William Westall, View of Sir Edward Pellews Group, Gulph of Carpentaria, 1802

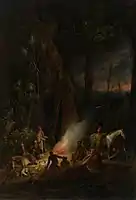

William Westall, View of Sir Edward Pellews Group, Gulph of Carpentaria, 1802 Augustus Earle, A bivouac of travellers in Australia in a cabbage-tree forest, day break, 1838

Augustus Earle, A bivouac of travellers in Australia in a cabbage-tree forest, day break, 1838 Conrad Martens, Campbell's Wharf, c. 1857

Conrad Martens, Campbell's Wharf, c. 1857

Gold rushes and expansion (1851–1885)

From 1851, the Victorian gold rush resulted in a huge influx of settlers and new wealth. S. T. Gill (1818–1880) documented life on the Australian gold fields,[16] however the colonial art market primarily desired landscape paintings, which were commissioned by wealthy landowners or merchants wanting to record their material success.[19]

William Piguenit's (1836–1914) "Flood in the Darling" was acquired by the National Gallery of New South Wales in 1895.[20]

Some of the artists of note included Eugene von Guerard, Nicholas Chevalier, William Strutt, John Skinner Prout and Knud Bull.

Louis Buvelot was a key figure in landscape painting in the later period. He was influenced by the Barbizon school painters, and so using a plein air technique, and a more domesticated and settled view of the land, in contrast to the emphasis on strangeness or danger prevalent in earlier painters. This approach, together with his extensive teaching influence, have led his to dubbed the "Father of Landscape Painting in Australia".[18]

A few attempts at art exhibitions were made in the 1840s, which attracted a number of artists but were commercial failures. By the 1850s, however, regular exhibitions became popular, with a variety of art types represented. The first of these exhibitions was in 1854 in Melbourne. An art museum, which eventually became the National Gallery of Victoria, was founded in 1861, and it began to collect Australian works as well as gathering a collection of European masters. Crucially, it also opened an art school, important for the following generations of Australian-born and raised artists.

Henry James Johnstone (also known as H. J. Johnstone), a professional photographer and student of Buvelot, painted the large-scale bush scene Evening Shadows (1880), the first acquisition of the Art Gallery of South Australia and possibly Australia's most reproduced painting.[21]

Robert Dowling, Group of Natives of Tasmania, 1860

Robert Dowling, Group of Natives of Tasmania, 1860 Nicholas Chevalier, Mount Arapiles and the Mitre Rock, 1863

Nicholas Chevalier, Mount Arapiles and the Mitre Rock, 1863 William Strutt, Black Thursday, February 6th (detail), 1864

William Strutt, Black Thursday, February 6th (detail), 1864 Louis Buvelot, Summer Afternoon, Templestowe, 1866

Louis Buvelot, Summer Afternoon, Templestowe, 1866

Australian impressionists (1885–1900)

The origins of a distinctly Australian painting tradition is often associated with the Heidelberg School of the late 19th century. Named after a camp Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton established in Heidelberg (then a rural suburb on the outskirts of Melbourne), these painters, together with Frederick McCubbin, Charles Conder[22] and others, began an impressionistic plein air approach to the Australian landscape that remains embedded in Australia's popular consciousness, both in and outside the art world.

Many of their most famous works depict scenes of pastoral and outback Australia. Central themes of their art include manual labour, conquering the land,[15] and an idealisation of the rural pioneer.[18] By the 1890s most Australians were city-dwellers, as were the artists themselves, and a romantic view of pioneer life gave great power and popularity to images such as Shearing the Rams.[18] In this work Roberts uses formal composition and strong realism to dignify the shearers[18] whilst the relative anonymity of the men and their subdued expressions, elevate their work as the real subject, rather that the specific individuals portrayed.[15]

In their portrayal of the nobility of rural life, the Heidelberg artists reveal their debt to Millet, Bastien-Lepage and Courbet, but the techniques and aims of the French Impressionists provide more direct inspiration and influenced their actual practise. In their early and extremely influential Exhibition of 9 by 5 Impressions of small sketches, their impressionistic programme was clear, as evidenced from their catalogue: "An effect is only momentary: so an impressionist tries to find his place... it has been the object of artists to render faithfully, and thus obtain first records of effects widely differing, and often of very fleeting character."[18]

Other significant painters associated with the Heidelberg painters were Walter Withers, who won the inaugural Wynne Prize in 1896,[22] and Jane Sutherland, a student of McCubbin. Born and raised in Sydney, impressionist John Russell spent much of his career in Europe, where he befriended the likes of Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet. He also wrote letters home to his friend, Tom Roberts, updating him on developments in French impressionism.

Charles Conder, A holiday at Mentone, 1888

Charles Conder, A holiday at Mentone, 1888 Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams, 1890

Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams, 1890.jpg.webp) Frederick McCubbin, Bush Idyll, 1893

Frederick McCubbin, Bush Idyll, 1893 Arthur Streeton, The purple noon's transparent might, 1896

Arthur Streeton, The purple noon's transparent might, 1896

Federation era (1901–1914)

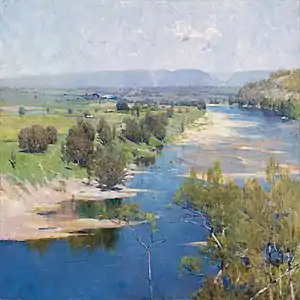

In 1901, the six self-governing Australian colonies federated to form a unified nation. Artists such as Hans Heysen and Elioth Gruner built on the Australian landscape tradition of the Heidelberg painters, creating grand, nationalist pastoral landscapes. Others moved on to successful careers in London and Paris, such as Rupert Bunny and Hugh Ramsay.

Hugh Ramsay, The Sisters, 1904

Hugh Ramsay, The Sisters, 1904 E. Phillips Fox, The Ferry, 1911

E. Phillips Fox, The Ferry, 1911 Elioth Gruner, Spring Frost, 1918

Elioth Gruner, Spring Frost, 1918 Hans Heysen, Droving into the Light, 1921

Hans Heysen, Droving into the Light, 1921

1920s onwards

Among the public, through the 1920s, modified forms of Impressionism were popular, with Elioth Gruner being considered the last of the Australian Impressionists.[23] The Australian Tonalist movement, originating in the writings and teaching of Max Meldrum, followed a 'scientific' transcription of tonal relations, making 'impressionism' a system, and opposed Modernist art then emerging pre-WW2 in the Angry Penguins and the Heide Circle influenced by refugees from Europe, and Australian-born artists' visits to England and France. Conservatives' attitudes to 'modern art' prevailed until the 1960s, institutionalised in the Australian Academy of Art (1937–1947), opposed by such groups as the Contemporary Art Society (established 1938 and continuing).[20]

The 1950s restored an interest in the Outback as subject matter in Australian art.[23] Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan toured the interior, sponsored by newspapers to document drought. They and Albert Tucker, in his Explorer series, sought to capture the ancient strangeness and a cruel infinity of the central Australian landscape.[23]

Splatt and Burton (1977) consider the 1960s a period in which public attention was being drawn to urban bushland and that landscape paintings of the 1970s carried through on the themes of environmental preservation and threats of destruction.[23]

List of artists

Art museums and galleries in Australia

Institutions

Australia has major art museums and galleries subsidised by the national and state governments, as well as private art museums and small university and municipal galleries. The National Gallery of Australia, the Gallery of Modern Art and the Art Gallery of New South Wales have major strengths in collecting the art of the Asia Pacific Region. Others include the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, which has a significant Australian collection of Western art. Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, and the privately owned Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, Tasmania and White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney are widely regarded as autonomously discerning collections of international contemporary art.

Other institutions include the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide, Newcastle Art Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery of Australia, the National Museum of Australia, the Canberra Museum and Gallery, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart, the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin, and the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth. A network of regional public galleries have existed since the mid-1800s and one, Castlemaine Art Museum, is unique in specialising in Australian art. The State Library of New South Wales holds a significant collection comprising more than a quarter of a million artworks,[24] many from the colonial period. More material is held by other national and state libraries.

Art market

The boom and bust cycle in contemporary art is evident in the 1980s colonial art boom ending at the time of the 1987 stock market crash and the exit of many artists and dealers, followed by the 2000s boom in Aboriginal dot painting and Australian late modernist painting, which ended at the time of the global financial crisis and growing collector and public interest in the international contemporary art circuit.

A 5% resale royalty scheme commenced in 2010 under which artists receive 5% of the sale price when eligible artworks are resold commercially for $1000 or more. Between 10 June 2010 and 15 May 2013, the scheme generated over $1.5 million in royalties for 610 artists.[25] Some buyers object to paying any resale royalty while others do not mind a royalty going directly to the artists. However, they worry about further red tape and bureaucratic interference.

In 2014/15 there was a rediscovery of colonial art at auction. Affordable 20th-century rural scene painting is buoyant. While the inflated northern hemisphere art markets had anticipating a massive correction in the Australian art market which transitioned to the middle market.

Socially oriented art events such as art fairs and biennials have continued to grow in size and popularity in the contemporary art scene.[26][27]

The smaller commercial galleries have struggled to remain in business in the 2010s in spite of a functioning economy, although there is little consensus on the reasons for this.[28][29]

A new market has arisen in China, where Australian artists are selling works in a traditionally local market: "While the Chinese have always had a passion for traditional Chinese art, according to global auction house Sotheby's, the surging interest in contemporary international art is a recent trend."[30]

The market for Aboriginal art is still very strong, on the national and international stage, since becoming a solid financial investment in the 1980s.[31] Not only do all the regional and State Galleries acquire significant collections of Aboriginal art, but private galleries are showing featured artists abroad.[32] Aboriginal artists are also represented in all the major landscape prizes Australia.[33] In 2019, "the Wynne prize, worth $50,000, was won by Sylvia Ken for her painting Seven Sisters – marking the fourth year in a row that the landscape prize has been won by Indigenous artists."[34]

Australian visual arts in other countries

The museum for Australian Aboriginal art 'La grange' in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, was one of the few museums in Europe that dedicated itself entirely to Aboriginal art.[35][36]

See also

- Arts in Australia

- Australian artist groups and collectives

- Australiana

- Australian Cartoonists' Association

- Australian feminist art timeline

- Photography in Australia

References

- "Indigenous art". Australian Culture and Recreation Portal. Australia Government. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Kakadu National Park". parksaustralia.gov.au. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Archived 27 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Ku Ring Gai Chase National Park, Sydney, Australia. Information and Map Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

-

- ABC Online 10.02.09 Pilbara Rock Art not Affected by Mining Emissions: Study

- Phillips, Yasmine: World protection urged for Burrup art. 13.01.09

- The spread of people to Australia, Australian Museum

- "The Indigenous Collection". The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. National Gallery of Victoria. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Arnhem Land Rock Art on Archaeology TV

- Australian Indigenous art, australia.gov.au Archived 16 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Hermannsburg School".

- "Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander art". nga.gov.au. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Protect Australia's Spirit - Griffith University". Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Protect Australia's Spirit: Interview with Prof. Paul Tacon and Jack Thompson on YouTube

- Art in Australia: From Colonization to Postmodernism. Christopher Allen (1997). Thames and Hudson, World of Art series.

- James Gleeson, Australian Painting. Edited by John Henshaw. 1971.

- "The Scott sisters collection".

- Australian Painting: 1788–2000. Bernard Smith with Terry Smith and Christopher Heathcote (2001). Oxford University Press.

- "National Gallery of Australia. Travelling exhibitions" (PDF). National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- McCulloch, Alan McCulloch, Susan McCulloch & Emily McCulloch Childs: McCulloch's Encyclopedia of Australian Art Melbourne University Press, 2006

- 'Evening shadows, backwater of the Murray, South Australia', Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Alan McCulloch, Golden Age of Australian Painting: Impressionism and the Heidelberg School

- Splatt, William; Burton, Barbara (1977). A Treasury of Australian Landscape Painting. Rigby. p. 36. ISBN 9780859020138.

- "Pictures Collections – Getting started", State Library of New South Wales

- Arts, Department of Communications and the (17 December 2019). "Resale Royalty Scheme". arts.gov.au. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Artforum.com". artforum.com. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Top 38 International Art Fairs To Attend". Le Paulmier Photography. 22 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Preiss, Andrea Petrie and Benjamin (11 May 2013). "Bleak picture emerges as galleries battle to hang in". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Fairley, Gina (16 August 2017). "Why are so many commercial galleries closing?". ArtsHub Australia. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Aussie artists eye cashed-up Chinese buyers spending big on contemporary art". Australia: ABC News. 28 September 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "History and Emergence of Aboriginal Art". Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Desert Blossoms of Bush Medicine 'Akwerlp Alpeyt Artna Arntetyew' – Art Exhibition". Michael Reid Gallery. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Indigenous artist wins landscape art prize". SBS News. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Tony Costa named winner of 2019 Archibald prize for portrait of Lindy Lee". The Guardian. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Fondation Burkhardt-Felder | Arts et Culture" (in French). Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Current Exhibition | Fondation-bf". Retrieved 13 February 2020.

External links

- National Association for the Visual Arts

- Australian Commercial Galleries Association

- Craft Australia's website

- Australian Video Art Archive

- Design and Art Australia Online

- Art Collector Magazine's Indigenous Art Centres Guide

- The Australian Arts Community – A free community website for the arts in Australia

- Art Prizes Australia, a free listing of Australian Art Prizes

_NMM_ZBA5754_(cropped).jpg.webp)